This year marks the 100th anniversary of Mamie Smith’s first records. In February of 1920, Mamie Smith made history as the first black woman to make blues recordings. Her first records opened the door to the race record market, and proved to be the beginning of recordings of the Harlem Renaissance. With this important anniversary in mind, many record scholars and collectors have been revisiting the story of how Mamie Smith made these historic recordings.

In 1965, Perry Bradford, Mamie Smith’s booking agent, wrote a book detailing the era right before the Harlem Renaissance. This book is called Born with the Blues, and it details the entirety of Bradford’s business with Okeh executive Fred Hager.

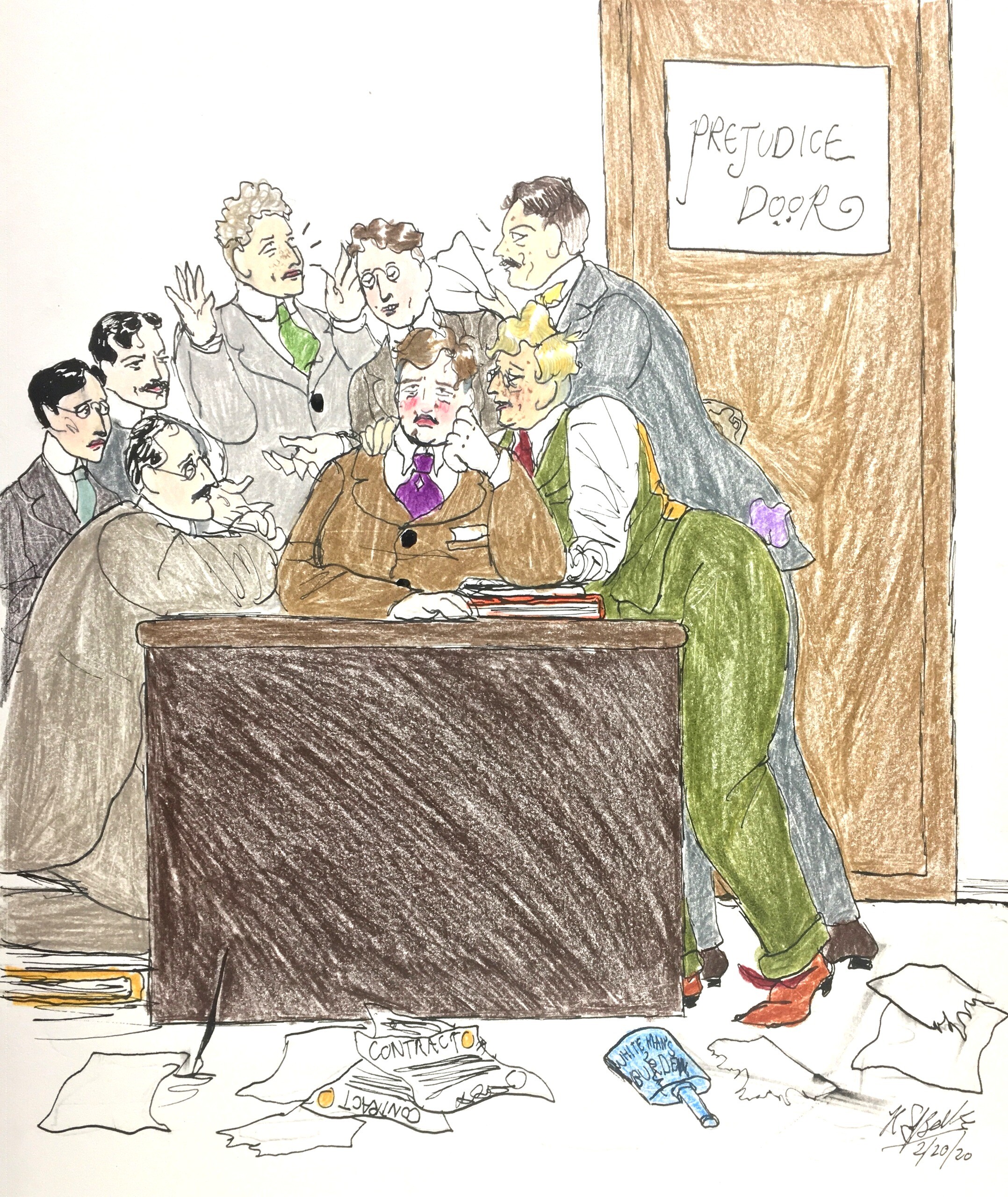

Ten chapters into the book, Bradford tells the complicated story of going to several record labs attempting to get various black women recorded. Bradford first went to the Columbia folks, and they threw him out. Next it was onto Victor, and amazingly Eddie King was a little more forgiving with Bradford and his hopes. He brought in Mamie to Victor to make a test record of “That Thing Called Love,” but after the test was done King insisted that they already had a substantial recording of the song. King was noted for his closed mindedness, what we’d call today racist. Undoubtedly her race was an issue with King, who was approaching his mid 50s by this time.

After King rejected Bradford and Mamie in the kindest way he could (which could come as a surprise, since he was known for his dirty words and unruly temper), Bradford quit his effort for a little while. But later, he decided to try the Okeh record lab for the second time (as he had tried them before). Here he was heading with the intention of seeing Mr. Hager, the only white executive who paid him any respectful attention. He had been bothering Hager’s young female secretary for a month, but hadn’t gotten in to see him face to face until he came across an old associate of Hager’s.

Bradford came across Chris Smith and Bill Tracy, songwriters of the previous decade, who buttered up Hager’s reputation to him, “I’ve known him for a long time and he’s a regular guy,” commented Chris, and Bill said, “…tell him I asked that he give you and audition for your colored girl singer [Mamie Smith].”

From 1905 to 1910, Hager published music with famous composer J. Fred Helf, and among those he published were Chris Smith and Bill Tracy. In 1910, Tracy wrote the words to Lewis Muir’s “Play that Barbershop Chord,” which proved to be a major success with Bert Williams and later with recording labs. This piece was among the last major successes that Hager published with Helf before quitting the firm and heading to Boston to make vertical cut recordings.

So with this in mind, next time he came in to see Hager he pushed aside the secretary and lab hands. The moment he mentioned Chris Smith and Bill Tracy, Hager poked through the office door with his brows up-curled and his eyes wide. Bradford finally got to see Hager in his office, and the more he massaged Hager’s ego, the more he was willing to talk business.

After old Hager was greased enough, Bradford pitched his idea of recording Mamie, and the reasons why Okeh should be the ones to do it. Hager and the other white record executives hadn’t realized that the market for authentic black blues would span all races and regions, and this was the thesis to Bradford’s patter. Hager was sold on this idea, but at first he wasn’t fully on board with recording Mamie. His first suggestion to Bradford was to have Sophie Tucker record the piece.

Bradford new that this wasn’t the way to go, but he complied. He took the song to Tucker but she wouldn’t sing it for Okeh, as she was contracted to Vocalion at the time. Bradford went back to old Hager to plug Mamie some more and try to budge him. Much of the issue that Hager took with Bradford’s proposal was that he was receiving many hateful letters from white communities. Many of them threatening to boycott Okeh products if they went through with recording black women such as Mamie.

“…Mr. Hager got a far-off look in his eyes and seemed somewhat worried…” is how Bradford described his reaction. Even after his deep brown eyed stare, Hager budged, and allowed for Bradford to bring Mamie in, hence the historic recording of “That Thing Called Love.” Hager insisted to the management at Okeh that these recordings would be a wise investment for them, though others like Charles Hibbard were a bit skeptical. Her first two records were made with the Okeh house orchestra, called the Rega Orchestra. They were directed on paper by Hager, but were really led in the lab by Hager’s partner Justin Ring.

Bradford was relieved that these were finally made, but there was more to be done. As he had kept up a good business relationship with Hager, he thought he’d make another proposal to him. After Hager went over all the good news about the record sales, Bradford proposed that Mamie sing with a small black ensemble (that he had not yet formed while pitching Hager). After awhile of piecing together a small band and rehearsing many times over, he came back to the Okeh lab with the group to record the famous “Crazy Blues”.

The band frustrated Mr. Hibbard, as he had been given them strict orders on how to play for their sensitive recording technology, and the band simply ignored his orders. After finally recording “Crazy Blues,” Hibbard threw his hands up and turned to an earnest Justin Ring, “You take over.” Hager witnessed this scramble, but even with that, continued to accommodate Bradford and Mamie’s style of leading, even to the ruffled feathers of his colleagues.

Bradford paid very high respects to Hager in this chapter, and throughout the book. He painted a very solid picture of the heart it took for Hager to go through with this decision, and along the way he made sure that Hager was remembered for his good deeds within the history of black music on record.

Here were his words paying respects to Hager:

“May God bless Mr. Hager, for despite the many threats, it took a man with plenty of nerve and guts to buck those powerful groups and make the historical decision which echoed aroun’ the world.”

In a sort of epilogue to this story, Hager kept papers for most everything he was involved with, but this was one story he drove that was nowhere to be found in what remains of his papers. He most likely kept something on this story, including a few letters from Bradford, but ultimately he decided to get rid of them with the others. He had no notion of this story being what he would be remembered for. He wanted to be remembered for the trips to the south when Okeh recorded all those hillbilly groups, black and white. Unfortunately Hager died a few years before he could see Bradford’s praises.

Despite his own reservations the recordings of Mamie Smith that Fred Hager approved were the start of the Blues craze, and opened the door for black performers in the 20th century. Whether he realized it or not.

R. S. Baker has appeared at several Ragtime festivals as a pianist and lecturer. Her particular interest lies in the brown wax cylinder era of the recording industry, and in the study of the earliest studio pianists, such as Fred Hylands, Frank P. Banta, and Frederick W. Hager.