In 2016, David Gilbert released his book Product of Our Souls: Ragtime, Race, and the Manhattan Musical Marketplace. This June, Archeophone Records released a companion compact disc subtitled The Sound and Sway of James Reese Europe’s Society Orchestra. While the CD and accompanying 56-page booklet focus on Europe’s life and works, the book itself spends its first two-thirds setting the stage for the arrival of Europe’s Clef Club. It’s a story that includes him, but also Ernest Hogan, Will Marion Cook, George Walker, Bob Cole, and the urban culturescape itself from Times Square lobster palaces to Tenderloin District piano dives haunted by Willie “The Lion” Smith and James P. Johnson.

In 2016, David Gilbert released his book Product of Our Souls: Ragtime, Race, and the Manhattan Musical Marketplace. This June, Archeophone Records released a companion compact disc subtitled The Sound and Sway of James Reese Europe’s Society Orchestra. While the CD and accompanying 56-page booklet focus on Europe’s life and works, the book itself spends its first two-thirds setting the stage for the arrival of Europe’s Clef Club. It’s a story that includes him, but also Ernest Hogan, Will Marion Cook, George Walker, Bob Cole, and the urban culturescape itself from Times Square lobster palaces to Tenderloin District piano dives haunted by Willie “The Lion” Smith and James P. Johnson.

The Story

Black history is usually taught with a direct leap from emancipation to the Montgomery bus boycott. Those seeking to fill the gap in college will also learn the turn of the century ideas of writers like W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington, transposed onto the later Harlem Renaissance. Because of their uncomfortable associations with minstrelsy, black entertainers before the 1920s are usually glossed over. Gilbert attempts in his book to fill in that gap and demonstrate how a cohort of pioneers “ragged uplift” and shifted the cultural marketplace from blackface minstrelsy to black musical professionalism from within the confines of that world. The book is directed at a wider audience interested in American history, rather than the tiny realm of ragtime enthusiasts. I hope Gilbert reaches that audience.

The story will be eye-opening to readers unfamiliar with how often, and successfully, minstrelsy and blackface were performed by African-American troupes. It was Ernest Hogan, a black man, who launched the craze for “coon songs” in 1893 with his wildly successful composition “All Coons Look Alike to Me.” He says he subbed in the word from an original verse which used the unprintable “pimp.” He went on to write many other songs and be one of the best known black stars of the era. Hogan defended his introduction of the word “coon” into popular culture because despite all of the negative ramifications, it simultaneously created lots of work for black entertainers.

Black Bohemia

In the 1890s a groups of black bohemians, including nearly everyone I will mention in this review, began to cohabit at or visit the Hotel Marshall in New York City. Among them were the most accomplished stars of black theater, arrangers of music, and performers of popular song. It was there in 1897 that Bob Cole wrote a “Colored Actors Declaration of Independence” and launched a black owned and run vaudeville company. The grating contradiction to modern readers is that the company’s success proceeded from its first show, A Trip to Coontown, co-written with another black entertainer, Billy Johnson.

Cole would go on to find a decade of success penning over 200 songs with the brothers J. Rosamond Johnson and James Weldon Johnson. His vaudeville acts would feature classical pieces and his songs avoided, as much as possible, the racial caricature many saw as intrinsic to ragtime in that era. As Gilbert puts it in the book, Cole and Johnson “utilized syncopated rhythm and dialect verse but presented both markers of black ragtime in a refined manner that whites loved.”

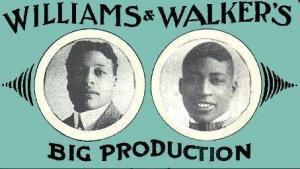

Bert Williams and George Walker became immensely successful vaudeville stars in the 1890s by selling their authentic blackness to white audiences with their act “Two Real Coons.” If blackface minstrelsy is supposed to be a recreation of African American song, dance, and humor, (they advertised) shouldn’t you prefer to see the real thing? It was their act that helped to launch the cake walk craze on stage and off, opening the door, slightly, for more public social dancing to come. Their 1902 production, In Dahomey, was the first by a black troupe to open in a main theater on Broadway.

“Ragging Uplift”

The Hotel Marshall community had a vision for black American artistry that insisted on the necessity of developing black cultural expressions on their own terms, developing them from within the culture and history of black Americans—as James Reese Europe put it later, “the product of our souls.” At first many felt, including notably Will Marion Cook, that this new area of art would grow from the spirituals that had found early success with the Fisk University Jubilee Singers.

As time went on it became clear that it would instead grow out of the earthier expressions of syncopation. Gilbert says in the book that they concluded that “Black authenticity was not buried in an imagined folk past; it was something that modern African Americans could cultivate, and even sell.”

He goes on to say, “No longer debating a question of folk or formal, (Hotel) Marshall musicians used commercial music—and its far wider avenues of distribution—to circulate their conception of a modern American artist citizen.”

This stood in contrast to a black elite, “The Talented Tenth,” who saw the only path to advancement as direct cultural adoption of European classical music and refined art. Many of the early theater works created by the Hotel Marshall cohort played on the humor inherent in this conflict: “[A]s they staked a claim in their own connections to Africa, Williams and Walker translated Black nationalist concerns onto the American popular stage in ways that challenged American white supremacy and confronted aspects of the Talented Tenth’s leadership, making issues like dress, deportment, and presentation seem parochial and elitist.” Aida Overton Walker, the young wife of George Walker, argued that black entertainers had more contact with whites day to day than any other black professionals and therefore more power to change public sentiment.

The Second Phase

Bob Cole, Ernest Hogan, and George Walker died in quick succession in 1909-10, closing the door on the first phase of black successes in musical theater. There would not be another African American run production on Broadway until Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle’s Shuffle Along in 1920. Many histories of theater skip over those ten years. Sissle himself, writing in the forties had a different interpretation. He referred to it as “the lost decade of jazz,” and gave the credit to James Reese Europe.

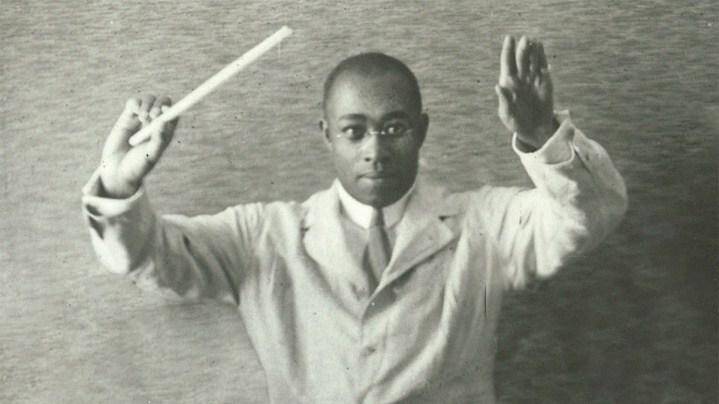

Europe had moved to New York City in 1904 with ideas for black uplift he had acquired through his classical training. He swiftly found success booking dance bands for the Wanamaker family and others among New York’s “400” richest families. He was a natural leader and organizer, an attribute his sister claimed went back to his earliest childhood.

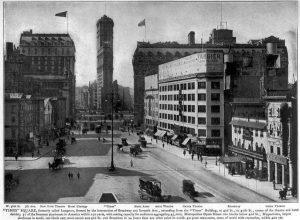

The New York Europe arrived to was musically much different than the one his music, and organizing, would leave behind. Lobster palaces had used waitstaff and kitchen help as after-dinner entertainment, performing for tips, ten years later Europe was booking the talented among them in those same restaurants as exclusive professional musicians.

Ragtime New York

Gilbert is best when setting the physical environment, including the physical interactions of Broadway, Times Square lobster houses, and Tenderloin dives. He details the willful creation of a modern black city-dwelling lifestyle distinct from the sharecropping South. Stiff competition had made for a New York sound distinct from the Midwest and South, with innovative pianists like Willie “The Lion” Smith and James P. Johnson gaining individual followings.

But “the string band restaurant ragtime resonated quite differently in sound and symbolic significance than the piano-led groups in black-owned nightclubs. Ragtime certainly played an important role in lobster palace dining rooms, but the individual musicians playing it did not.” In the restaurants “they played quieter, performed mostly hit songs of the day, and called less attention to themselves through improvisation.”

The string band ragtime itself had replaced “gypsy” string bands. Europe’s bands, when following a gypsy string band as a livelier after-dinner dance act, would lead off by ragging the last waltz played to accentuate their difference.

The Clef Club

There were precedents for what Europe would do with the Clef Club. The Frogs were an eleven man club of elite New York black entertainers who, from 1908, held annual Frog Frolic benefit concerts that, by attracting an audience of paying blacks from all social levels to hear syncopated music and dance, demonstrate that the class divisions around entertainment were not as hardened as they are often made out to be.

The Clef Club, though, was different in both purpose and scale. Incorporated by Europe in 1910 it served as both a booking agency and labor union. In the era before telephones were available in most buildings members could hang around the club and wait to be called out on a gig, day or night. (The term “gig,” according to Noble Sissle, was actually coined by Europe during this period.) The club consisted of up to 200 professional musicians who were required to meet certain standards of dress and behavior while on jobs.

In exchange for that professionalism, and the availability of any number of musicians on a moments notice, Europe was able to negotiate premium wages from elite clients. Club members were booked all over the Northeast and even on yachts around the world, at times commanding as much as $35 a day per musician. This was while most workers, white or black, made less than $2.

“The fact is, colored musicians charge more than white musicians,” James Weldon Johnson responded to a letter writer complaining that black musicians were pushing whites out of the market.

“Never before in the history of New York have colored musicians been in such demand, and the prediction is made that owing to the dance craze this demand will increase” wrote Lestor Walton in a column about black musicians’ invitation to the American Federation of Musicians union. That union acknowledges in their own 1970’s history that the success of the Clef Club forced them to open their doors.

Selling “Black Authenticity”

“Europe selectively reinforced aspects of white America’s racialism to call attention to other items on his agenda,” writes Gilbert. He played on racialist tropes about black musical giftedness in order to raise the cachet and perceived value of his bands. Though most of the Clef Club members could read music, they were not allowed to in public so that white audiences could maintain the illusion that it all just came naturally.

Europe himself led the full 125 member Clef Club Orchestra, which had a large contingent of banjo’s mandolins, harp guitars, and multiple pianos in addition to normal orchestral sections. “We have developed a kind of symphony music that no matter what else you think, is different and distinctive, and lends itself to the playing of the peculiar compositions of our race” he told one critic. “While Europe based his orchestra on a European symphony, he arranged the concert selections in ways that highlighted his unusual amalgam of “folk” instruments and their distinctive rhythmic pulses” writes Gilbert.

The Concerts

The Orchestra held successful concerts at the Manhattan Casino, a black venue, for two seasons before being invited to desegregate Carnegie Hall in 1912. While the Casino events included dancing and vaudeville acts, the Carnegie Hall concert was only about the music. The New York Evening Journal swelled antecedence by writing a day before the show that this new “black” music was the “only music of our own that is American—national, original, and real.” It was “an ear opener” said folklorist Natalie Curtis-Burlin remembering it in 1919, it was when “colored musicians became professional.”

Much has been written about the significance of this event. Gilbert sees it as “A historic moment when the heterogeneity of Negro music in New York began to calcify into a racially determined, single iteration of black popular music—when black’s music became ‘black music.’” He draws a correlation between Europe and his predecessors’ success in marketing blackness as an immediate precursor to the “race records” marketed to African Americans after 1920, and the general segregation of music along racial lines for the rest of the century.

“Europe’s successes helped narrow the meaning of black ragtime, turning it from a commercially produced American cultural commodity into the exclusive cultural expression of African Americans.”

“As Europe maneuvered between the often contradictory mandates of his audiences, he transformed black performance from a marginalized and largely stereotypical form of entertainment into a symbol of modern American culture.”

Partnership with the Castles

Gilbert explores interesting topics like the relationship between the acceptance of social dancing and a turn away from skit-acting as the primary focus of black produced entertainment. He also ponders at length why the dancing couple Vernon and Irene Castle would choose Europe’s Clef Club to be their exclusive band for the critical 1913-1915 period. The Castles traveled with Europe to 31 cities in 28 days and allowed him to record several songs for the Victor Talking Machine Company bearing their names. (Europe’s complete Victor output is available on the accompanying CD.)

The Castles’ mission was to legitimize black dances for middle class audiences in a time when the New York Sun could write that ragtime dances were “rhythmically attractive degenerator[s]… which hypnotize us into vulgar foot-tapping acquiescence.”

Gilbert concludes that there was a sexiness to having a black band to make up for the Castle’s removal of sex from the dance floor, but it was also because of Europe’s success in marketing his band as the very best available. The Castles could only be associated with the very best. It was a symbiotic relationship.

The Sound

What about the music itself? The CD captures the eight sides released by Europe for Victor, including several he wrote for the Castles. It then, for comparison, includes other bands of the day performing the same songs. To fill it out are several tracks penned by Europe, but never recorded by him. The booklet says that while it’s easy to only see these performances as a jazz precursor “close listening reveals a world as vibrant and fully formed as any in American history.” But I’ll warn you that this is a CD to enjoy as education. “Even with [the drummer] Gilmore’s syncopated dance rhythms the music does not ‘swing,’ nor does it groove much like jazz or blues.”

Gilbert’s race-infused academic analysis may be clearer than either the romanticized notions inherited by the general public about the era, or the culture blindness of earlier authorities on this topic. It may also be off-putting to some readers. But if you find these ideas captivating do yourself a favor and read the book. Do us all another favor and encourage Archeophone to produce more valuable CDs with 56-page liner notes by acquiring this one.

CORRECTION: In the print edition of this review I stated that Aida Overton Walker lived into the 1950’s and was a Broadway Choreographer. In fact, she died in 1914 a few short years after her husband George Walker. During those few years, in addition to her own routines she fed public demand for her more famous late husband by often playing his familiar songs and routines in male drag.

The woman I had in mind was actually Will Marion Cook’s wife, Abbie Mitchell. She was already a star when they married, when she was just 14, so she continued to use her professional name. Her career included all aspects of the entertainment industry from the 1890s until her death in 1960. Her last stage role was “Clara” in the 1935 premiere of Porgy And Bess, after which she worked as an acting coach and choreographer. She deserves a biography all her own, and aside from short essays in compilations about African American artists, she doesn’t seem to have had one.

The Product of Our Souls:

Ragtime, Race, and the Birth of the Manhattan Musical Marketplace

by David Gilbert

UNC Press (www.uncpress.org)

Paperback; 312 pp; $29.95, ISBN-10: 978-1-4696-31

The Product of Our Souls:

The Sound and Sway of James Reese Europe’s Society Orchestra

Various Artists

Archeophone ARCH 6010 (archeophone.com)

22 Tracks, 74:37 total; 56 page full-color booklet

Also Read: 1920: The Year Broadway Learned To Syncopate

Joe Bebco is the Associate Editor of The Syncopated Times and Webmaster of SyncopatedTimes.com