Jazz is often thought of as America’s first cultural export. This isn’t entirely true. Long before jazz, or even ragtime, America had developed a form of entertainment that reflected our unique heritage, and that entertainment was popular all over the world. The blackface minstrel show as a structured and predictable format coalesced in the 1840s and quickly found favor in English speaking nations and beyond.

Jazz is often thought of as America’s first cultural export. This isn’t entirely true. Long before jazz, or even ragtime, America had developed a form of entertainment that reflected our unique heritage, and that entertainment was popular all over the world. The blackface minstrel show as a structured and predictable format coalesced in the 1840s and quickly found favor in English speaking nations and beyond.

The wearing of blackface for comedic effect has a history dating to before the Revolutionary War, but the minstrel show formalized the practice. A minstrel show had set character roles; an interlocutor and end men, generically referred to as Tambo and Bones who were always in blackface. Everyone might be in blackface, or everyone but the interlocutor, or no one besides the end men, but always the end men.

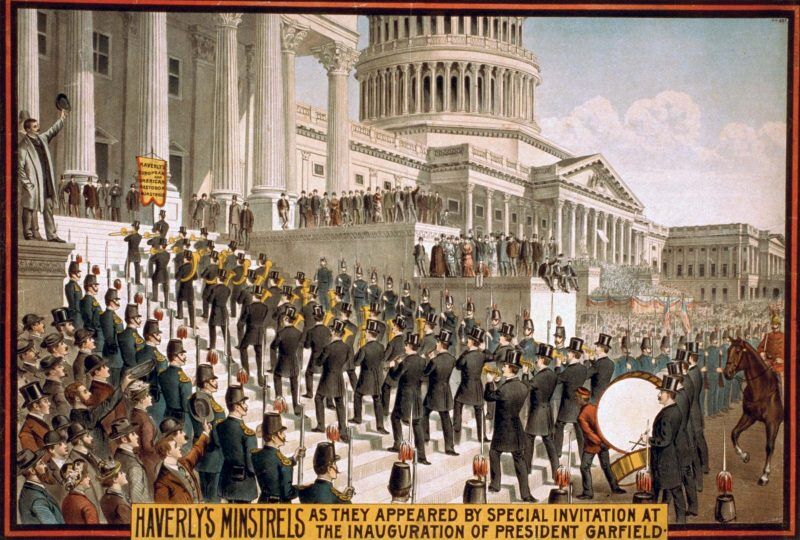

A blackface minstrel show had a structure beginning with a “first part” consisting of comedic banter and song and the traditional announcement “Gentlemen, Be Seated!” The middle section, known as the “olio” consisted of variety show entertainments and often a “Stump Speech” mocking politicians and the news of the day. That section would eventually spin off on its own to become vaudeville.

The conclusion of the show would be an organized skit, it could mock anything from popular opera to plantation life, or even be a legitimate play. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a regular feature. That play was so popular and familiar that despite antislavery intentions its characters morphed into common minstrel caricatures including the “Mammy”, “Pickininny” and of course “Uncle Tom”.

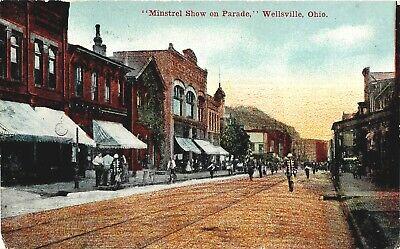

A minstrel show was a full evening of entertainment often announced with a daytime minstrel parade as the company walked into town.

While the heyday of huge traveling minstrel shows petered out after the 1890s the format found it’s way onto records, radio, and even onto television. Several full segments portraying minstrel shows aired on network television as late as 1953, often with dixieland bands accompanying.

While the heyday of huge traveling minstrel shows petered out after the 1890s the format found it’s way onto records, radio, and even onto television. Several full segments portraying minstrel shows aired on network television as late as 1953, often with dixieland bands accompanying.

By then the racist jokes were mostly out, but it just wouldn’t be a minstrel show without the blackface, which was very much on display. Community minstrel shows, often held in churches and civic clubs, continued into the sixties and beyond. They relied on costume suppliers and the numerous guidebooks for staging them.

The history itself gets complex very quickly. Many African Americans, usually themselves in blackface, were among minstrelsy’s biggest stars. Many troupes were integrated and there were prominent all black minstrel troupes touring not long after the Civil War. Black performers advertised the plantation songs and dances they portrayed as “the real thing”, even though they were often from prominent black families long established in the North. Some of the most offensive songs written in the era were by black composers. Stage productions from much lauded pioneers of black theater like Will Marion Cook had titles like “Bandanna Land”, played on plantation themes, and drew mixed audiences.

Such collusion didn’t end as early as one would like to think. The Chicago Defender, the most influential of the Black newspapers, praised the revival of minstrelsy on the radio in the 1930s, and Noble Sissle, famous for bringing black musicals to Broadway in the 20s, lamented the growing cries to eliminate blackface minstrelsy from television in 1949. On the other hand his partner, Eubie Blake, while talking to black intellectual writer Albert Murray during the 1970s, insisted that it be made clear in his story that “I never wore cork”.

The minstrel show always mirrored public expectations. Though even in the 1860s it was seen as nostalgia many of the songs heard would be current hits, and the skits often reflected current events.

Radio minstrel shows of the 1930s were accompanied by the latest swing hits alongside throwbacks to Stephan Foster. Many first generation jazz musicians, black and white, got their start in minstrel shows. The next generation unquestioningly played in settings involving blackface minstrel show elements throughout the swing era and into the Dixieland revival of the 1950s.

The most vicious racism in minstrel shows occurred during the “Coon Song” craze of the 1890s which stood on its own, apart from minstrelsy. It was inspired by oneupsmanship in the new record format and between sheet music suppliers. Coon Songs were obviously, even intentionally, distasteful, and the worst of the genre burned itself out fairly quickly.

That period was also the pinnacle of minstrel performance by sheer size, with some stage shows involving hundreds of performers. The billboard displays and other horrifying advertisements that we associate with minstrelsy now are often from this period. That 1890s peak heralded the decline of stage minstrelsy as a professional form in the next decades. It distorts our historic memory of what was heard at a blackface minstrel show in the 1870s or 1930s.

More benign, sometimes even sympathetic, racial tropes, characterizations, and imagery were the norm before and after the 1890s. In the early days of minstrelsy many attending int the north had never met a Black person and they earnestly sought an authentic experience of what was to them a foreign southern culture. In the later days of minstrelsy, the decades covered in this book, good humored characterizations made it harder for the general public to perceive what the problem was.

This complex picture doesn’t excuse the past. People should have known better, and some did. The Chicago Defender’s praise of radio minstrelsy was in response to another Black paper’s condemnation of it. By the time Victor and Columbia set down to capture a complete minstrel shows on record in 1902 and 1903 public sentiment had changed. The labels included little racial humor on those highly staged recordings. The blackface minstrel show had by then begun its rebranding as a wholesome traditional entertainment. Women and marriage taking the brunt of the jokes, surrounded by rat-a-tat cornball comedy.

This change was partly effected through the efforts of Black organizations like the NAACP. The easing of racial disparagement in public art was a stated goal of elite Black creators like Cook, Sissle, and James Reese Europe. Their cooperation with the broader entertainment structure allowed them to humanize characters within the common format. Their use of plantation settings was akin to attempts to humanize the portrayal of Native Americans in Westerns; there’s still going to be a gunfight, and 50 years later it might all look terrible.

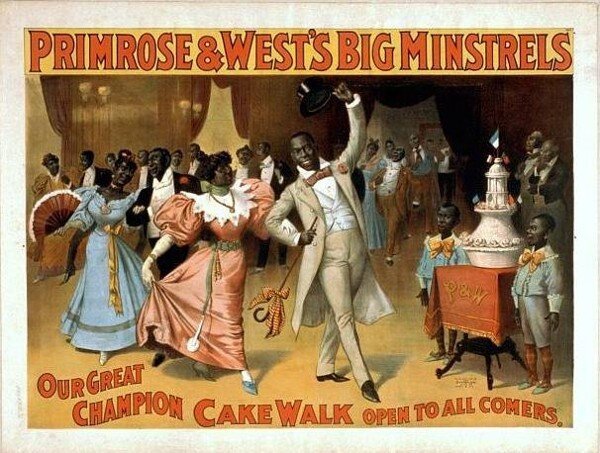

There have been many books on blackface minstrelsy. Most are origin stories chasing the genre’s 19th century roots and peak popularity. The legacy touring companies, like Primerose and West were on their last legs in the early 1900s and died out entirely by the 20s. Those books, focused on the stage, miss all that happened off of it and give modern readers the impression that it all ended long ago. .

There have been many books on blackface minstrelsy. Most are origin stories chasing the genre’s 19th century roots and peak popularity. The legacy touring companies, like Primerose and West were on their last legs in the early 1900s and died out entirely by the 20s. Those books, focused on the stage, miss all that happened off of it and give modern readers the impression that it all ended long ago. .

The Minstrel Show in Mass Media: 20th Century Performances on Radio, Records, Film and Television tells the rest of the story. It tells it completely and succinctly, without getting into any politics beyond those shaping events in real time. The focus is on performances themselves. The performers, the skits, and the media on which they appear. At an approachable length, and as riveting as any secret knowledge, it should be included in every syllabus that touches this subject. These are the unvarnished facts from which good cultural analysis can be drawn.

The book begins with a reasonably concise 25 page history of minstrelsy before the recorded sound era. This is plenty for anyone who hasn’t read on this topic previously. The balance of the book is broken into chapters detailing attempts to recreate blackface minstrel shows, in whole or in part, on records, radio, movies (and cartoons), and finally television. Each section tells the complete story of that medium from beginning to end, and then tells the briefer version of that story in the UK market. This was a good choice as a chronological approach would have been cluttered.

The main section is followed by extensive appendices including a discography of minstrelsy on record and capsule biographies of both prominent minstrel troupes active after 1890 and early recording artists who worked as minstrels.

Don’t confuse what he intends to cover with Collins and Harlan, Two Black Crows, Amos and Andy, or other blackface comedy duos on records, radio and television. In all sections of the book the focus is kept tightly on recreations of full format minstrel shows. Other forms of racialized skit comedy and blackface were frankly too pervasive for inclusion.

Programs like Amos and Andy were offshoots of the minstrel show, but what author and media historian Tim Brooks intends to chronicle are those areas where the show itself never went away. His previous book Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890-1919, is recognized as a classic in the field, and sets him up as the best man for this job. It’s startling that so little has been written on blackface minstrel shows in the context of 20th century media.

The longest chapter covers attempts to capture the minstrel show on record. Physical limitations of 2-4 minute cylinders initially limited portrayals of blackface minstrelsy to the “First Part”, the opening humorous banter of the interlocutor and end men. Later, as mentioned above, both Victor an Columbia made attempts to recreate a full minstrel Show. This involved recording a number of records to represent expected parts of the show. A very early concept album.

The longest chapter covers attempts to capture the minstrel show on record. Physical limitations of 2-4 minute cylinders initially limited portrayals of blackface minstrelsy to the “First Part”, the opening humorous banter of the interlocutor and end men. Later, as mentioned above, both Victor an Columbia made attempts to recreate a full minstrel Show. This involved recording a number of records to represent expected parts of the show. A very early concept album.

Brooks has concluded that these early records do provide a glimpse at what a real show would have sounded like at the turn of the century. Nearly all of the actors had minstrel stage experience, and the buying public itself would know what to expect.

These early recordings, which may be our best evidence of what an early blackface minstrel show consisted of, are covered in detail in the book. They are also collected on the companion double album, At the Minstrel Show: Minstrel Routines from the Studio, 1894-1926 from Archeophone Records. Those wishing to understand better what made the shows so popular and long lasting should look to these records for clues.

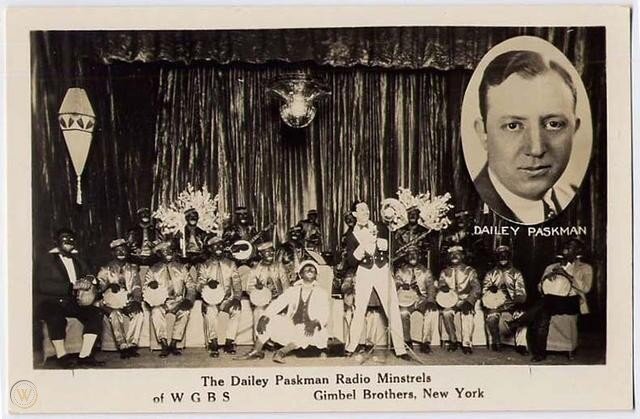

Minstrelsy was nearly dead as a format until radio came along in the 1920s. The radio chapter introduces the ardent supporters in the business who recognized that a familiar structure was a good way to fill the airwaves. Minstrel hours proliferated. Though their were no more prestigious touring shows, radio reached enough households to support several large live shows. Actors appearing on radio, even when they weren’t before a studio audience, would often appear in blackface to get into character.

Minstrel shows were a movie staple from the silent era to the 1950s. Indeed one of the earliest experimental talkies from 1913 presents a tightly rehearsed minstrel show. Tightly rehearsed because they needed to lip sync! This chapter covers some well known stars appearing in blackface including Shirley Temple, Judy Garland, and Bing Crosby. Brooks points to small time Westerns for more accurate portrayals than those found in major releases, in part because some of the actors had real world minstrel show experience. Cartoons are covered briefly, he rightly points out that their racial imagery could fill its own book.

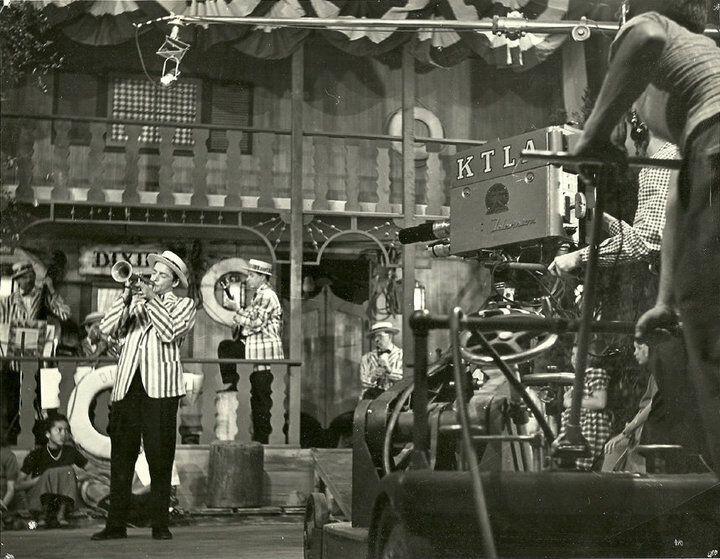

Television portrayals of minstrel shows brought the use of blackface back to the fore. Unlike many of the movies, which had been set in another period, shows like Dixie Showboat were modern variety hours involving integrated casts. The cognitive dissonance was growing too much. Under growing pressure portrayals of minstrelsy and blackface were off the airwaves in the US by 1953. In the UK however… I’ll let you read about that one for yourself.

An interesting theme running through the book is the decline in racial comedy over time. Even in the heyday of blackface minstrelsy racial jokes were only part of a broader field of humor. Jokes were mostly silly puns, and telling old jokes and groaners was often the point. The end men sometimes won the day over the interlocutor standing in for a know-it-all boss, everyone was supposed to be likable, even the villains. Much of the humor is timeless, and repeated on late night shows and slapstick comedies today.

As it turned out you could have a blackface minstrel show without any racial humor at all. Most of the later portrayals in radio and television didn’t use racial humor, or at least weren’t overt about it. The fact that someone is in blackface makes race implied but there was nothing specific to the jokes themselves that required it. (Even now, sans blackface, the straight man interrogating the funny man is the basis of American comedy.) Sometimes there wasn’t even any racial dialect. But a minstrel show, it turned out, just didn’t work without at least the end men in blackface. Even on the radio.

I don’t mean that racism itself wasn’t rampant in all these media, or that the characterizations using dialect weren’t inherently racist whatever the banter, only that the instances of race based humor in minstrel shows decreased in frequency and softened over time while the blackface and established characters remained, often unchallenged.

The thing that is the most glaring to us now, the imagery, was the most tolerated aspect then and the thing that proved hardest thing to part with. Had wearing cork disappeared in the 1890s, but a formalized custom of outdoing each other with ever more offensive ethnic jokes continued on in polite society, would we be talking about it the same way today? Or is it the imagery, the character roles, and the fact of blackface itself that haunts us.

Even during the 1960s many felt that as long as the jokes weren’t cruel there was nothing wrong with a white guy with shoe polish on his face pretending to be an ignorant rube or pining for his “Mammy”. There are Americans not yet 70 with memories of appearing in middle school minstrel shows wearing blackface. Some are from families that rooted for Martin Luther King. Standing on six generations of American tradition they honestly didn’t see the problem. That’s something to consider when an out group today claims an injury that seems small.

The Blackface Minstrel Show in Mass Media: 20th Century Performances on Radio, Records, Film and Television, by Tim Brooks; Mcfarland Nov. 2019; Paperback 290 pages, ISBN-13: 978-1476676760

Note: none of the images used in this article appear in the book.

Joe Bebco is the Associate Editor of The Syncopated Times and Webmaster of SyncopatedTimes.com