With reservations, I’ve chosen to weigh in on the debate started by the publisher’s column asking: Is the term “Dixieland Jazz” racist? Almost everyone will disagree with something I say here. Keep in mind that my ideas represent my own impressions of a word. Impressions I share with many others. I’m writing with the underlying assumption that people who use the word are well intentioned and have never considered the racial implications.

It’s hard to see something when you are inside of it. If your public life is defined by volunteering in a Dixieland Jazz Society you will naturally consider someone who comes along and tells you the term’s no good an ignorant fool. The use of “Dixieland jazz” to describe either a particular style of music, or pre-swing jazz as a whole, is common among our subscribers.

At 40, I’m much younger than our average reader and because of that I try my hardest to catch up on the 60 years of jazz revival history I wasn’t around to experience. I browse through 1970s Mississippi Rags as if they were my morning news.

I’m also older than many of the musicians we cover in the latest resurgence of traditional jazz. Those musicians playing bars in St. Louis and Pensacola, Philadelphia and Milwaukee, and their supporters, will be the core of our readership twenty years from now. I hope in this essay to reflect some of their reservations about the term “Dixieland.”

I also follow bands, young and old, playing traditional jazz in Europe and Australia, and that gives me additional insight on this topic. When it comes to words, especially this one, geography is important. Europe is seen as being much more progressive than America, ideas about language use that would be vanguard positions in the United States are public policy in the Nordic countries, but it is easy to have blind spots.

In the United States members of the Society for Creative Anachronism dress up in European middle ages attire and camp out together at elaborate gatherings. There is a similar subculture in Europe romanticizing the Indians of the Old American West. They camp out in red face dressed in Native American garb. They mean nothing by it. Some of them don’t even realize Native Americans are real, or that there are any left, least of all that they might be offended by this “tribute.”

Use of the term “Dixieland” is another blind spot, both in Europe and among some fans in America. Europeans of all ages use the term more than Americans do. It has a utility there that many older Americans think it still has here. To them it describes “New Orleans jazz”, and that is the kind they are trying to play.

It also connotes trappings of riverboats and parasol parades. Looking from Europe that kind of fantasizing about America is all part of the fun. But for many Americans, particularly people of color, it has a darker connotation. There is a reason that African American musicians playing European jazz festivals take pains to say the music they are making is “New Orleans jazz” and definitely not “Dixieland.” We should follow their lead.

What is “Dixieland Jazz”?

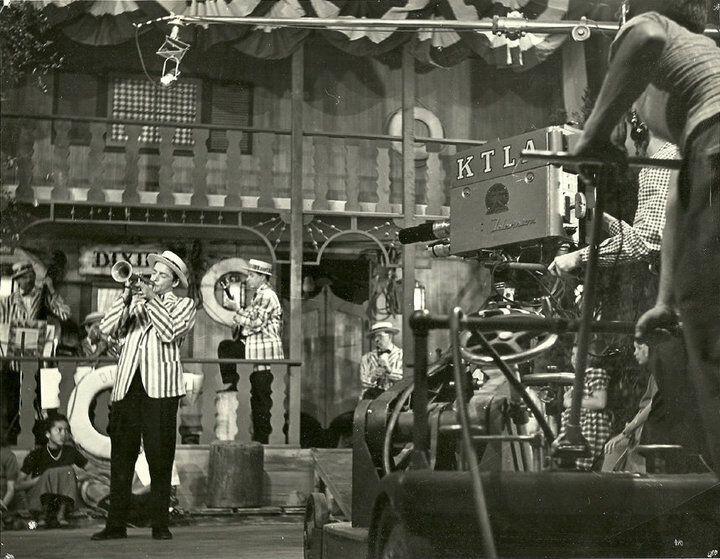

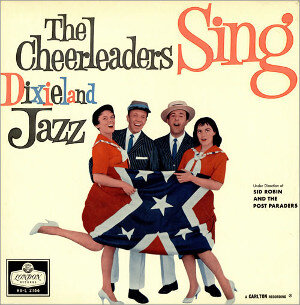

Dixieland jazz as commonly understood, at least by people my age, was a mid-century commercial art movement that harnessed the imagery of old Dixie. The trappings of the “Old South” including boater hats, Confederate flags, parasols, mint juleps, and riverboats. The music itself was a part of a larger whole and inseparable from it. Without tying the spirited music of the 1920s to a wholesome and happy go lucky South you don’t have Dixieland, you simply have pre-swing jazz.

Dixieland jazz as commonly understood, at least by people my age, was a mid-century commercial art movement that harnessed the imagery of old Dixie. The trappings of the “Old South” including boater hats, Confederate flags, parasols, mint juleps, and riverboats. The music itself was a part of a larger whole and inseparable from it. Without tying the spirited music of the 1920s to a wholesome and happy go lucky South you don’t have Dixieland, you simply have pre-swing jazz.

Dixieland jazz, understood this way, was a commercial subset of a broader interest in the revival and preservation of pre-swing jazz that began in the late 1930s. A revival that continues, and has increasingly avoided the term “Dixieland”.

Why “Dixieland”?

The whole concept of “Dixieland” was rather silly. The advances in jazz after it became a craze in 1917 occurred outside of New Orleans and enrolled musicians who were not from that city. What’s more, James Reese Europe in New York, Sid Le Protti in San Francisco, Wilbur Sweatman in the midwest, Gus Haenschen in St. Louis (who may have recorded the first jazz record), Duke Ellington‘s peers in Washington DC, and string ragtime ensembles everywhere were creating music that was “almost jazz” even before the diaspora of the New Orleanians.

By 1923, because of the feedback loop of popular recordings, King Oliver and his peers were playing in a style that had evolved greatly from what they played in New Orleans in 1916. The breakthroughs of Louis Armstrong and others were made in New York, Chicago, and even in Europe, with help from sidemen originating in all those places. Calling the many styles of 20s jazz, and the revival of those styles, by any geographic moniker doesn’t reflect reality.

It was even dubious then. When King Oliver named one of his later bands the Dixie Syncopators northern bands had already been claiming southern origins for decades. It was a marketing gimmick and a good one. The Dixie Syncopators was a name in the spirit of many groups that had come before like the “Real Alabama Minstrels.” No one in 1926 would have heard it otherwise. Many people twenty years later still heard it that way.

“Dixieland jazz,” that mid-century subset of revival jazz, took on a standard seven-man instrumentation and a distinct sound. Neither had been common in the pre-swing era. That instrumentation was used on some of the most iconic studio recordings of the late 20s but didn’t reflect the diversity you’d find on stage.

A pre-1920 New Orleans jazz band would be more likely to have a violin than a piano, and a bass and guitar more often than a tuba and banjo. No one would confuse the most admired recordings of the 20s with a mid-century group and what you would have heard in venues, not limited by the three minutes of a recording , would have been different yet again.

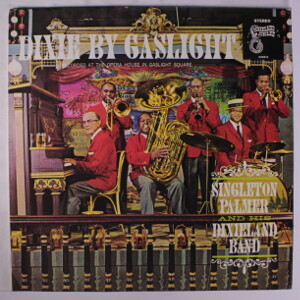

Revival era Dixieland highlighted fast ensemble playing without much blues feel and it focused on good times, it has been called “the happiest music on earth.” There were regional variations of course. For example, the music of St. Louis’ Gaslight Square was notably bluesier than what was heard on the West Coast, and the revival in Britain had its own flavor.

A few ’20s bands greatly influenced the Dixieland sound. Most were those of white jazzmen like the Halfway House Orchestra in New Orleans or the many Red Nichols’ groups. Chicago style bands, their forebears being The New Orleans Rhythm Kings, Bix Beiderbecke’s Wolverines, and the Austin High Gang were critical in contributing a standard repertoire.

Beginning in the 40s attempts were made to reproduce the “true” New Orleans jazz sound of the 1910s and even trace it back to roots in the 1890s. These produced inconsistent, sometimes contradictory results, indicating that music in the Crescent City was as diverse then as it is now.

Recording companies didn’t reach New Orleans until jazz had been a national sensation for nearly a decade, and they didn’t record much. All the jazz records made in New Orleans during the 1920s could fit on a three CD set.

People in search of the “true” New Orleans sound were reliant on gentlemen like Jelly Roll Morton and Bunk Johnson, both eager to please researchers by exaggerating their importance to the prehistory of the music. While there are people today who can recreate that proto jazz sound with reasonable credibility, you wont hear it performed very often. It isn’t jazzy enough.

Is Dixieland Jazz White Music?

Some people assert, usually as a disparagement, that modern Dixieland bands are inheritors of a distinctly “white style” of New Orleans jazz with roots as far back as newsboy spasm bands of the 1890s. They have some good historic reasons for doing so but I would argue that music evolves and personal influences have never been that clean cut.

Exceedingly few bands have consciously pursued playing “white jazz”, and the records on the turntables of revivalists were from a diverse set of early recording artists from across the country. As the actual recordings from New Orleans were scarce, to the extent they were striving for a true New Orleans sound it was a sound they pursued with educated imagination rather than one inherited horn to horn.

There was a lot of very good music made in the Dixieland style, and there is still good Dixieland being made. That sound is so synonymous with the West Coast that if you say West Coast style rather than Dixieland many people will know what you mean.

A Dixieland band at this point is trying to be a Dixieland band, not a 20s style jazz band. When they book themselves as such the venue and audience know what they are getting. It will likely be five or seven older white men playing as hot as they can muster. That can be great music. If a band is booked to play Dixieland near you, go listen. When you see those records in the bin, check them out.

Some of those old white guys have interesting stories to tell about jamming with the 20s era jazz musicians who were still active while they were young. They are usually a lot more serious about the music and its history than you would gather from the matching polo shirts. You can be sure they didn’t get into Dixieland for the money. Many have devoted a lifetime to making sure this music survived.

The practitioners and fans of mid-century Dixieland were almost entirely white, but they were white people with a respect for Black music who sought to preserve it. As a consequence of their efforts to track down the “real thing” there was also traditional jazz played during the revival that didn’t sound much like what we think of as Dixieland.

During the revival many African American musicians, especially those from New Orleans, rejuvenated careers and kept them going as long as health would allow. Their gutbucket style, which didn’t sound much like the recordings of the ’20s either, had a strong influence on certain revivalists, particularly those from Europe. It became the sound of Preservation Hall and is still part of the stew today, especially in New Orleans, but also in Toronto and several other cities that modeled their local style on the revival era musicians in New Orleans.

What About?!?

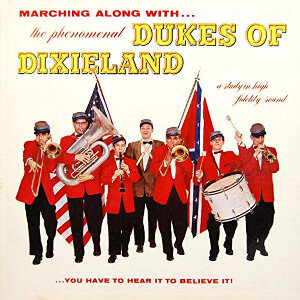

Because I can already hear the typewriters purring I will say that many Black musicians also appeared with Dixieland bands, or bands using that term to describe revival jazz. Most notably the biggest band of all, the Dukes of Dixieland. The Dukes had the benefit of being from New Orleans, often sharing a stage with Black led bands in that still segregated city. That does count for something.

Before even going to press I was alerted to tubist Singleton Palmer. He was a star of St. Louis’ famous Gaslight Square during the 50s and 60s. Palmer led an all-Black jazz revival band under several names. All of those names included the word Dixieland.

Before even going to press I was alerted to tubist Singleton Palmer. He was a star of St. Louis’ famous Gaslight Square during the 50s and 60s. Palmer led an all-Black jazz revival band under several names. All of those names included the word Dixieland.

No example you could give of a Black musician using the term Dixieland, or playing with a band that did, or otherwise seeming to accept it counters what I will argue. What Louis Armstrong said about a word in the 1950s is completely irrelevant to a discussion about whether that word is appropriate today. The question should be, “If Louis were around now would he feel comfortable playing ‘Dixieland’?” Would a young Black horn player choose to study and play a style called Dixieland?

Many African Americans during the minstrel era appeared in blackface and were among the biggest stars and most prolific writers of the “coon song” craze. In a society that was so structurally against them, few would have felt the common use of a loaded geographic term worth more than a grumble. For many, the chance to be appreciated for playing the music they enjoyed overshadowed any reservations they might have about what people called it. “Dixieland” simply didn’t signify as much as it does now, being at the time much closer to a neutral term like “New England”. In 1950 the South was still the Jim Crow South, still Dixieland, the nuances of meaning have shifted under the weight of another 70 years of American history.

Racially based objections to the term “Dixieland” can be found, even among Black musicians taking those gigs. But thankfully, many things acceptable at that time, aren’t acceptable now.

A reader told me about an experience she had at Jimmy Ryan’s in the 1970s. The famous club had a sign that said “Dixieland jazz played here”, but as a member of the house band Roy Eldridge would explain to patrons that he never used that term for the style because many musicians had grandparents who were slaves in Dixieland.

The Dixielanders Weren’t Racist

I believe the term is racially charged, but I don’t believe the fans who embraced it were more racist than the general population, and many of them were notably less so. They were, after all, enjoying music with strong associations with African Americans.

I believe the term is racially charged, but I don’t believe the fans who embraced it were more racist than the general population, and many of them were notably less so. They were, after all, enjoying music with strong associations with African Americans.

Nor is anyone today racist for using what has been the common term for something their entire lives. A term that you’ll still spot in your local newspaper. “Dixieland jazz” doesn’t sound to the ear the same way an older person saying “Colored” does, and maybe it never will. It still has a critical use in describing a particular musical moment so it won’t disappear completely.

The primary reason that a segment of the jazz revival came to be called “Dixieland” is that a handful of influential fans during the swing era began using the term to describe pre swing music at their private record spinning sessions. These “Hot Clubs”, named after their love of hot jazz, called pre swing music Dixieland to honor The Original Dixieland Jazz Band. The ODJB, as they are known, were the first jazz band to record, sparking the original jazz craze in 1917. It wasn’t even 20 years later that these hot clubs, fearful of the changes brought by swing, began trying to preserve the earlier style.

The term Dixieland became increasingly widespread in the 40s before being harnessed by the record companies in the post war years. “Traditional jazz” was the competing term favored by Turk Murphy at the early 1940s dawn of the West Coast revival.

I’m excluding from this essay the few actually racist voices in the revival. They were not indicative of the whole and perhaps were reactionary to it. Racist intent is not what is wrong with the word Dixieland. But there is one bit of history that must be included.

The ODJB was an all-white band whose founder, Nick LaRocca used the new attention the 40s revival brought him to claim a white origin for jazz. Racist statements are magnified by historians, and the average fan at the time was unaware of them, but there did exist a small number of vocal members of the revival eager to embrace Papa Jack Laine as the white Buddy Bolden.

There have been recent efforts to restore the place of important white contributors to early jazz. These are an attempt to correct earlier historians who had often applied racial inherency to music that in reality emerged from a melting pot.

Some early jazz historians used genetic terminology to connect jazz to Africa and ignored the many white people who helped develop the style. Their early jazz histories sound as cringeworthy today as quotes from people in the 1950s who claimed jazz was invented by whites, or the sometimes worshipful way well meaning fans fetishized “uncorrupted” Black musicians from New Orleans in the 1960s. This essay may sound cringeworthy within my lifetime, God willing it will, that’s progress.

Efforts to uncover a nuanced multi-racial history of jazz can be taken the wrong way, especially when someone who thinks of jazz as an exclusively Black art form is confronted by someone whose favorite musicians of the twenties are primarily white. White musicians were vitally important to the development of jazz, in part because they had an easier time recording and traveling. The privilege they had doesn’t subtract from the value of the music they made or the influence it had on Black musicians during that time and later.

From the earliest days of jazz, groups like the New Orleans Rhythm Kings were honored to have men like Jelly Roll Morton record with them in the studio. The teenage white kids hanging outside the Black clubs in Chicago in the early 20s were there to learn, not to steal. Many of them continued to share what they learned into old age, working alongside later generations of Black musicians throughout their careers.

Why The Term “Dixieland Jazz” is Racially Charged

There are many who have read this far and are honestly thinking, “How is Dixieland racist?” They’ve never considered the concept before. “Dixieland Jazz” was still in my school textbooks in the ’80s. It is still listed on Wikipedia as referring to all pre-swing styles of jazz rather than to a specific revival style. If those are to be held as the ultimate authorities than people who insist it means pre-swing jazz as a whole are technically correct.

I would counter that “colored” also has its archaic connotation in the dictionary, as it should for anyone needing to look it up. The problem with “colored,” for anyone wondering, is the association with the Jim Crow era color line. We might even use it now, rather than “people of color,” but a hurt clings to the word from an earlier age when it had legal implications. “Dixieland” carries a similar hurt for a significant portion of our population.

In discussions of the word in older traditional jazz periodicals racial implications are never included. It is an omission that frankly shocks me. As organizations fretted over the music dying and removed “Dixieland” from the names of festivals the reason given was that Dixieland had “corny” associations, not racist ones. It seems to be a cultural blind spot among the devotees of that generation — like the Europeans dressing up as Indians and doing war dances. It also indicates just how overwhelmingly white the scene had become.

What’s in a Word?

Disney’s intent with Song of the South, released in 1946, was a benign, even a progressive wish to tell the Uncle Remus stories of the unique African American Gullah culture of the South Carolina and Georgia Sea Islands.

The accusation that the film was racist because it left out any indication of racial animus was made almost immediately but most Americans could live without the scars of slavery in a children’s movie.

By the 1980s that once rare reaction to the film had become so widespread that it has never been released for home video. Dixieland jazz used some of the same iconography and the public’s instinctive reaction to the term “Dixieland” has evolved along the same lines.

“Dixie” refers to the geographic and cultural area that was the slave-owning Antebellum South, and to the unreconstructed Jim Crow South that sought to preserve that culture. Saying “the south” refers to the same geographic area but any historic or racial context would require a modifier. Compare, “I’m going down south”, to “I’m going to Dixieland.” The word carries its own luggage. The term Dixie refers to an order of things wherein Black Americans were subjugated, and implies that they were happier that way.

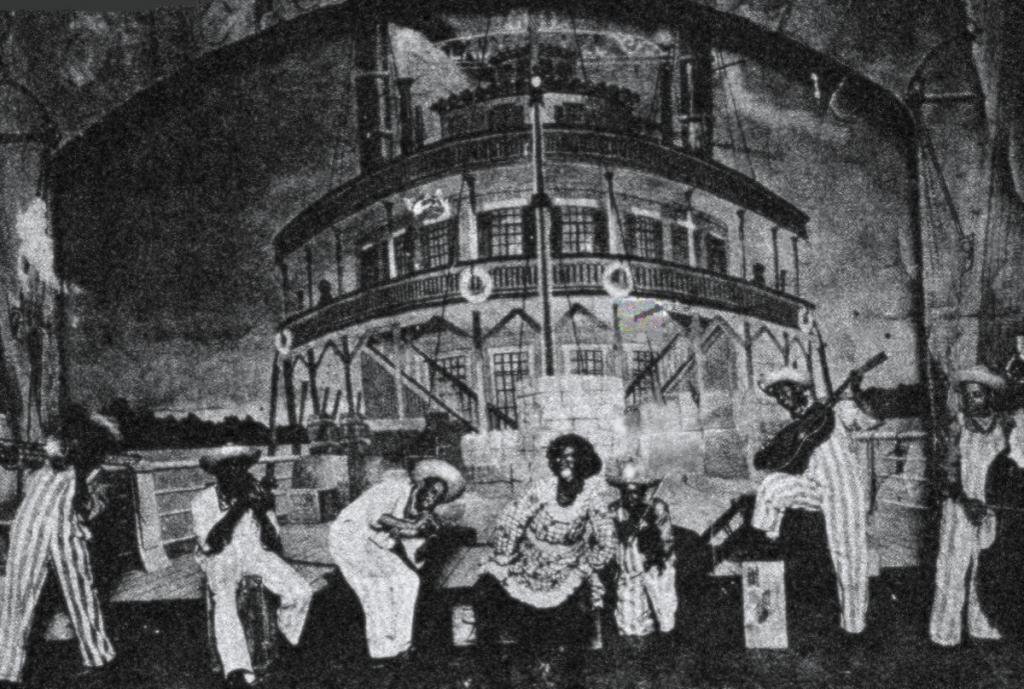

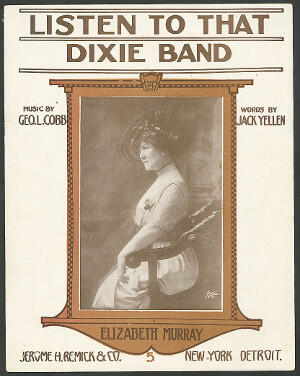

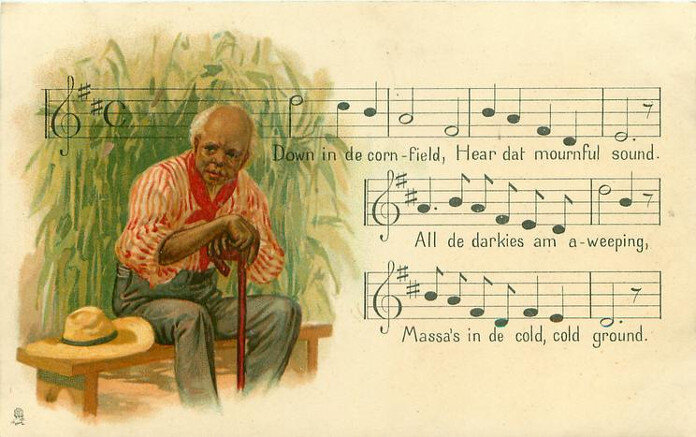

The most common trope of minstrelsy was of a Black man longing for his master and his Dixie home. These songs, almost all written in the North, tugged on the heartstrings in a country full of recent immigrants and children leaving the farm for the big city. Many showed great empathy for the displaced. Dixie is an idea. Dreams of fun-loving lassitude in a pastoral South hit the spot for a newly industrialized North, but they also painted a picture of a southern idyll that never was.

Dixieland and Minstrel Culture

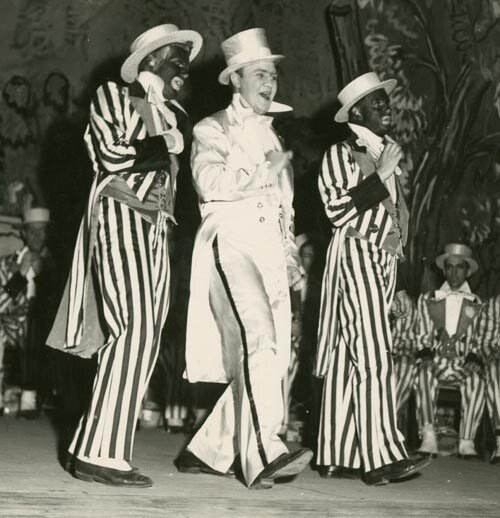

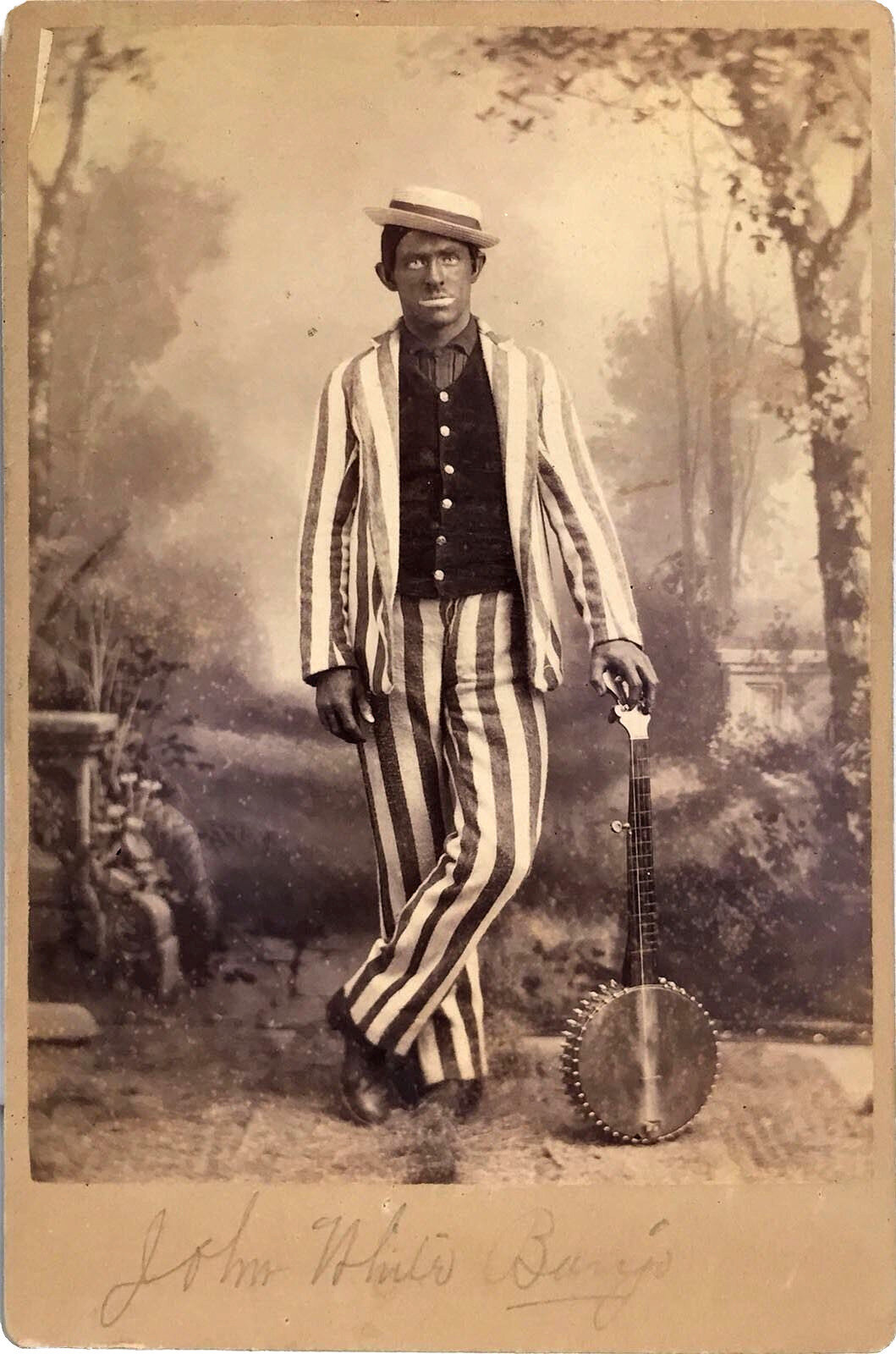

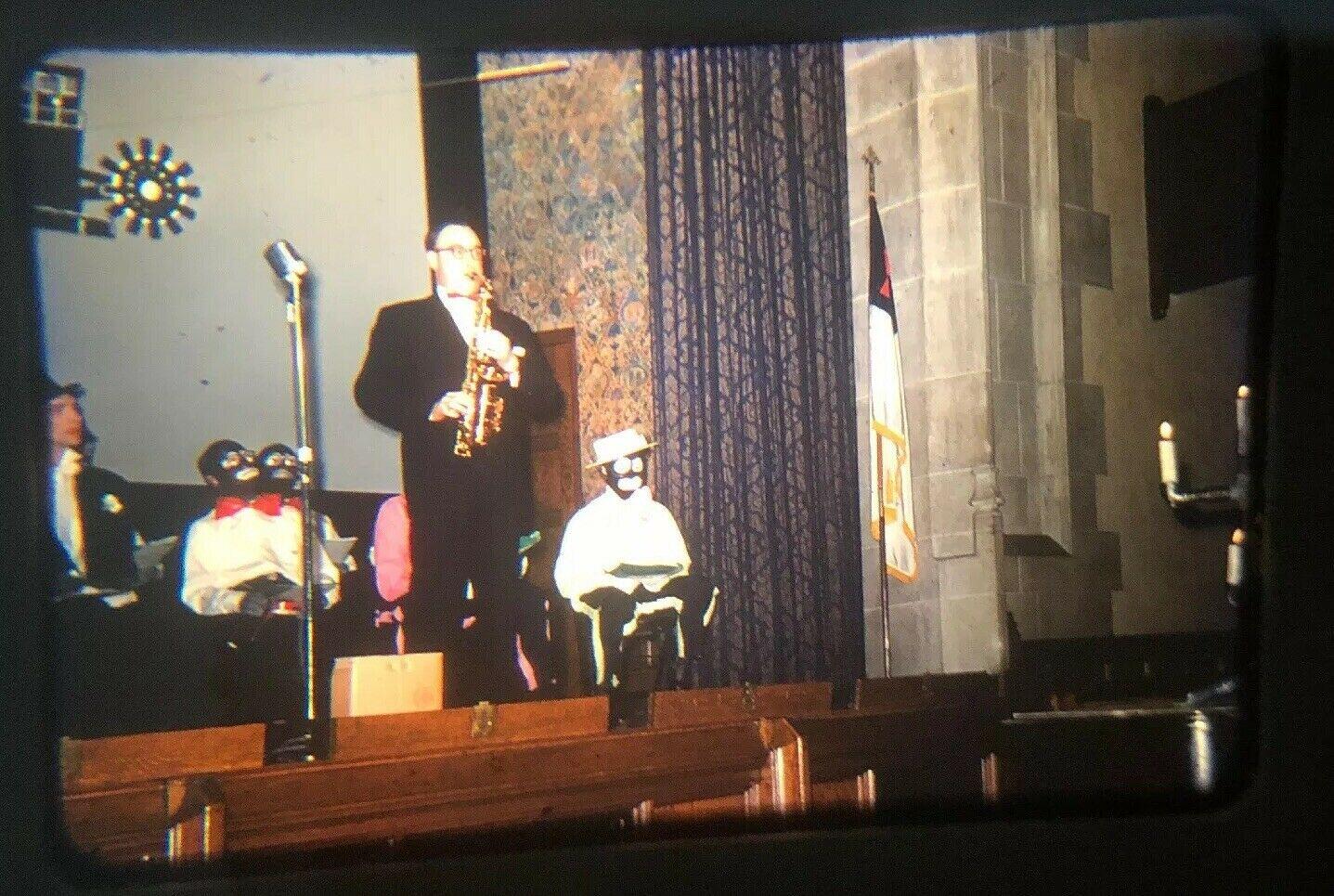

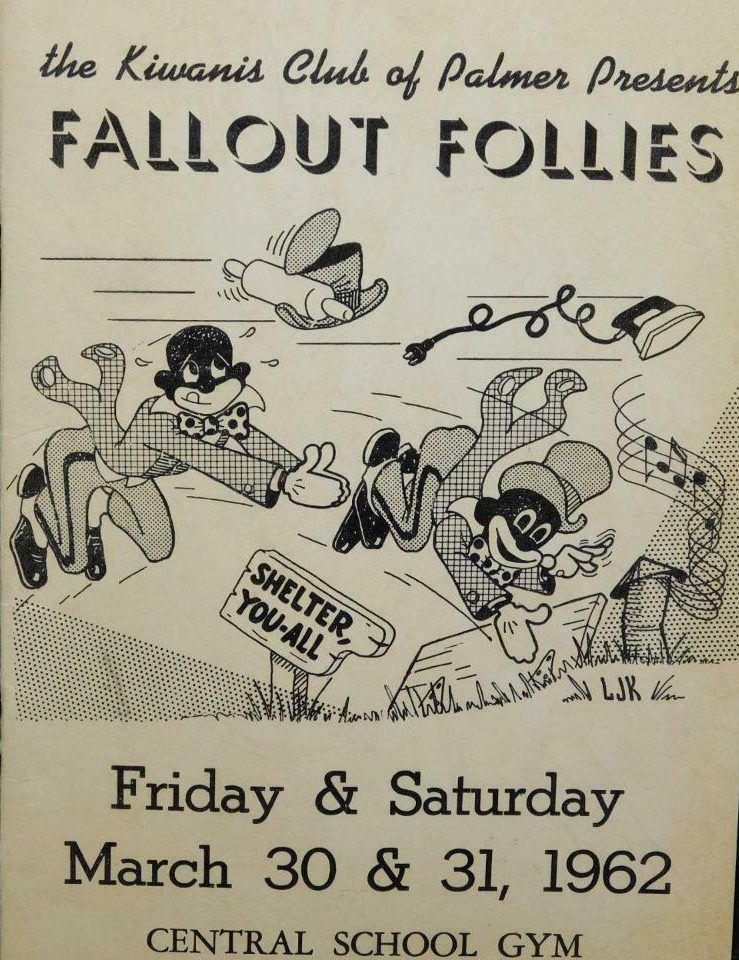

The happy go lucky Dixieland of the 1950s record covers was simply minstrel show imagery stripped of blackface. People still “wore cork” in small town church bazaars, but as the LP era dawned you couldn’t have that sort of thing on albums anymore.

It is hard to fathom now just how central blackface culture was to American identity at the time. During the early civil rights era it became unacceptable in public performance, but having been what entertainment was for over 100 years it couldn’t just disappear.

Minstrel routines continued in comedy minus the racial elements. Hee Haw consisted primarily of recycled material from the vaudeville stage and you’ll still hear jokes on the Late Show that debuted in the banter of “darky records”.

Minstrelsy, sadly, became associated with Dixieland jazz in the public mind. Visual clues from minstrelsy were promoted by record companies, and adopted by bands and their fans. When people thought of how turn of the century entertainment should look and sound, that’s what they pictured, because that’s what they had been taught to picture.

Some would try to deny this point. In addition to minstrel shows in Vermont and Pennsylvania which continued in altered form into the 2010s, one using purple face, I found a group in Spain which gave themed minstrel performances in full blackface as late as 2009, calling it an educational exercise. The accompanying music is described as Dixieland music, performed by a band with Dixieland in its name. And that is exactly what it is. The music in this performance sounds nothing like what you would have heard in a minstrel show before the 1940s when Dixieland first became the dominant music heard in that context. Minstrel show audiences before 1940 would have heard plaintive renditions of ancient tunes like “Grandfather’s Clock”. Jazz, in particular Dixieland, was only tacked on later to please modern audiences who expected a little more rhythm. Though there are incongruous examples of top swing bands accompanying minstrel shows in the 1930s it was hardly the norm.

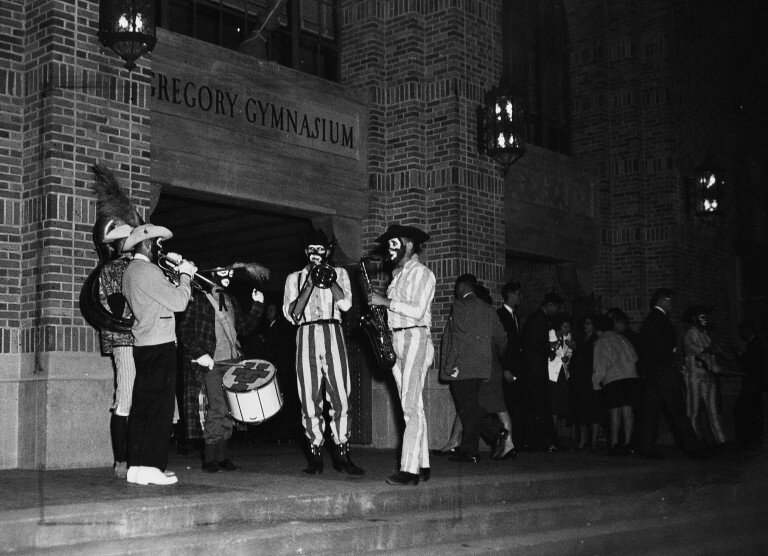

The iconic Dixieland Jazz outfit of a boater and stripes wasn’t nearly as common in performance during the 40s and 50s as it is made out to be. The successful groups were not dressing like that. But the local groups, closer to the minstrel scene, and frequently accompanying small time minstrel shows were.

Boater hats were commonly worn nationwide early in the century, and a striped suit appeared in a variety of contexts. One of those contexts was the backing musicians of a minstrel show, but many other outfits were common, from plain suits or tuxedos to costumes that recall clowns or royal fools. The full motif we now associate with Dixieland album covers emerged in elaborate 1940s Hollywood portrayals of minstrel shows. Al Jolson appeared on the big screen as a minstrel in blackface as late as 1946.

The boater and stripes outfit had become cultural shorthand for a form of entertainment; like polyester Disco clothes now evoke the 1970s. It rang true in cultural memory even though it wasn’t all that accurate to what performers actually wore.

That Dixieland garb, when instruments are in hand, also evokes an image of singing waiters, or of a Black band playing for white folks on a river excursion boat. Subservient relationships. Riverboat iconography became prominent in the commercial portrayal of Dixieland Bands. White guys, dressed as a Black band, without the blackface.

Interestingly, what the bands were allowed to play for white folks on the early riverboats was actually too flat and constrained to be called jazz. The real jazz was happening in town.

Similar things happened with barbershop singing and barrel house piano. Our idea of a barbershop quartet is now of four white guys. The African American origins of the style have been entirely erased.

In the post blackface era, the easiest thing to do was to whitewash. Because white performers could no longer parade as Blacks they created new aesthetics, sometimes by writing African Americans out of the story. The 1950s old time piano album covers went for an ahistorical western look while preserving brothel imagery that was historically accurate. It was okay to show scantily clad women as long as they, and the piano player, were white.

Why It Hurts The Music

Jazz itself developed later than the heyday of racial minstrelsy which had already passed its peak by 1905. Professional blackface continued, but was in terminal decline by 1917 when the first jazz records were cut. Minstrel performances on stage and screen, despite lingering on for decades, soon became nothing more than performative throwbacks to an earlier time. Something akin to teenagers today donning tie dye to stage the 1967 musical Hair. Minstrel shows in the jazz age celebrated a time before jazz. A music that came to signify the upending of social mores that existed before the Great War.

Even though many jazz musicians had experience accompanying minstrel routines for traveling shows, the jazz music played in the late teens and twenties had nothing to do with blackface minstrelsy. In the environment of the mid 20th century, as minstrel shows continued on the fringes, nostalgic Dixieland Jazz became the anachronistic accompaniment to them. Much like the movie The Sting, filmed in the 1970s and set in the 1930s, featured a sound track of Ragtime from the turn of the century. Looking back from the 1950s, pairing music from the 1920s with comedy routines from the 1890s-1915 period didn’t seem like a stretch. And the audiences enjoyed Dixieland more than they would the more accurate marches and parlor songs.

Successful jazz musicians of the twenties were proudly separate from the stage theatrics of minstrelsy. They exuded class, wearing the latest suits. In fact, if you read their memoirs, they obsessed over them. Black bands did play for white audiences but they primarily performed for the Black fans in the northern diaspora enraptured by the new hot sound.

To both white and Black audiences of the 20s jazz represented a hard break from the past, a new age. Black musicians were keenly aware of how much had changed in such a short time. For the first time music by Black people was being created and sold with Black audiences in mind, and black entertainers could begin to carve out full careers that didn’t rely on playing to stereotypes. That empowerment is the true legacy of early jazz and it need not have ahistorical associations with minstrel culture, but because of the commercial Dixieland boom it has acquired them.

Most of the white fans didn’t even notice the minstrel imagery. Local churches still had fundraisers where people appeared in blackface. Many would swear it was good old fashioned fun and they didn’t mean anything by it. By comparison a group of white guys on a record cover in boaters and stripes was pretty soft.

The potential fans of traditional jazz among the Black population did notice. When you have grown up experiencing the watermelon humor on the cartoon reel at the movie theater you aren’t going to join something called a Dixieland band using that same imagery to sell records.

That is the saddest thing about the adoption of the word Dixieland. It’s a signifier of unwelcome. I believe it to be the single most important reason there aren’t more African Americans enjoying early jazz today. “Dixie”, after all, was the tune traveling Black musicians are said to have performed on their entrance into southern towns to announce that they were “good negroes.”

The standard higher education framework for jazz was being laid out during the bop era, at the same time as early jazz was acquiring unwarranted minstrel associations under the canopy of Dixieland. That has led to a long tradition of teaching those pursuing careers in jazz to look down on early jazz and especially the revival. But 1920s jazz wasn’t associated in its time with minstrelsy, it was innovative, part of the Renaissance that moved Black performers beyond those tropes. Black jazz entrepreneurs like King Oliver, Perry Bradford, and Clarence Williams were among the first African Americans to build careers in entertainment that didn’t rely on self-deprecating stereotypes. Their music should be taught as a source of pride.

You sometimes hear that Black musicians perceive of jazz before bop as “Uncle Tom music”, played to entertain white folks. But early jazz in New Orleans, Chicago, and Harlem, was music played by Black people in their own segregated communities with only a few breakout performers playing the big white clubs where the money was better.

Mixed race groups and friendships between Black and white players helped dismantle the de facto (and sometimes legal) segregation in the North. The celebrity of Black jazz and swing musicians, for the first time based on their talent rather than their Blackness, opened minds and hearts for the civil rights era to follow.

To the extent these inaccurate attitudes toward traditional jazz have basis, their basis was not in the historical music but generated by the commercial trappings of Dixieland, the look and feel of a Disneyfied minstrelsy. These attitudes calcified in the field of jazz education, where 70 years later students can gain Masters Degrees without having ever heard the Hot Five.

(Disney, to its credit, removed the word Dixie from the southern themed sections of their parks around the year 2000. They are now in the process of re-imagining Splash Mountain with a Princess and the Frog theme, rather than the original Song of the South theme.)

The press was eager to cast the playing of traditional jazz as reactionary and portray the fans and musicians of Dixie and Bop in oppositional terms. Among most of the musicians themselves the “war” between the Moldy Figs and the Boppers was nothing but a myth. Musicians in the first two generations of modern jazz studied and loved the music of the twenties.

Why Don’t More Black People Play Traditional Jazz?

There are people who claim Black musicians as a rule have consistently wanted to be at the cutting edge of jazz. If true, that would be strange. The vast majority of musicians of any color are craftspeople playing either what they enjoy or what pays the bills. Very few make any effort to push the envelope and even fewer do it successfully enough to be noticed.

There are many Black jazz musicians playing in styles not much advanced from the earliest bop of 80 years ago. Musicians completing graduate programs in jazz routinely chose to focus their careers on hard bop, or other specific styles that were fresh when their great-grandparents were young.

University jazz programs teach that jazz is best as a personal, noncommercial expression of the artist — played for oneself rather than an audience. The proposition that the African American community as a whole accepts this exalted ideal, and therefore dislikes the entertainment value of early jazz, seems weakly supported.

With each new musical trend since the Cake Walk of the 1890s Black musicians have been at the fore, developing musical and fashion styles focused on entertaining. The African American community has celebrated entertainers for being commercially successful in a way that has rarely been true of white performers.

No one within the Black community would look down on someone forming a doo wop group, or an old school R & B band, or a James Brown tribute band, or a ’70s style funk band, or perfecting a throwback 1980s rap technique. These would all be seen as honoring heritage, and many such groups exist. Even within ragtime, which was once almost synonymous with “Coon Songs”, several of today’s most popular festival performers are African American, a few are even composing new ragtime works in the 125 year old style.

It is an anomaly that you won’t find an all-Black band playing in the style of King Oliver, or specializing in the compositions of Clarence Williams. Not one. So the question becomes, why?

People gravitate to musical styles that carry a sense of identity, be that hippie jam band music, punk rock, hip hop, modern jazz, bluegrass, or folk. The adoption of the term “Dixieland jazz,” and the social baggage that went with it, created an identity for pre-swing jazz that raised a no trespassing sign for Black musicians. That stigma also caused an untold number of white musicians to pursue other, more welcoming, more authentic feeling styles.

The question “why don’t more Blacks play Our Kind Of Music,” also contains its answer in the word “our.”

I’ve read accounts of Black traditional jazz musicians turned down by festivals because they don’t know how to play “our” music. I don’t mean the Soul Rebels Brass Band or other modern New Orleans acts that wouldn’t fit. I refer to committed historical purists, musicians who in Europe play for the most discerning traditional jazz aficionados. So while they might not think of traditional jazz “played right” as white music, people in the American Dixieland community sometimes make the assumption that only white people know how to play it.

I’m also certain that no one calling the music Dixieland today has any intention of offending. Feeling that a call for a language change is ridiculous, especially when it is a word important to your own identity, is not inherently racist. A few however do seem insistent on applying the term “Dixieland” to musicians who say they don’t want it applied to them. If nothing else changes because of this essay, that must stop.

The Future

The swing community is very interested in spotlighting the Black stars of the early days and is doing a great job of welcoming Black dancers. Black musicians playing swing are as unconcerned with how they will be perceived as they would be playing any other historically Black music. Sure, swing never had the same stigma as Dixieland, but it was hardly thought of as progressive. I find this hopeful.

With the continuing renaissance of swing dancing, a segment of musicians have naturally gravitated to the earlier pre-swing jazz. As more trad bands pop up, they create new opportunities to play. I spot Black sidemen in their 20s all over the country. Their number isn’t large, and these are bands playing local bar scenes, not hitting the festival circuit, yet, but it is certainly a good sign for the future.

The slow disassociation of traditional jazz from the term “Dixieland” may be why I now find racially diverse acts among the youngest of today’s trad bands. Few young musicians worry about a stigma accompanying traditional jazz. If it were given its due in music school programs I am sure we’d have a flood of talented musicians eager to devote at least some of their time to it.

If Not “Dixie” Then What?

So what do I think about using the term, in this paper, or in public? I would never ban it. If a band uses the term to describe themselves, I will use it as a descriptor. And I have done so in my reviews. It appears hundreds of times on our website. Likewise, if I need to refer to a mid-century group of that particular style, I may use it to distinguish them from other styles. I’m not going to edit it out of historical band names — King Oliver’s D**** Syncopators just doesn’t look right.

I do encourage bands, clubs, and event hosts who don’t want to offend to stop using it. My understanding of American history, vaudeville, minstrelsy, and the blackface era informs my current views. But had you asked me as a teenager in the 1990s, before I knew any of that, I would have told you the term sounded racially charged. That means a typical person under 50, having never considered the issue at all, may have that reaction even if they can’t articulate why.

At this point when you say “Dixieland” no one can be sure what you are referring to. There are people who use it to mean all pre-swing jazz, others who apply it to a particular revival style, and many who reject it outright. That has been true since Turk Murphy voiced his dislike for the word in the ’40s, and Roy Eldridge and Eddie Condon nodded in agreement. The confusion about giving pre-swing jazz a name owes itself to a word that should have never been a contender.

Like Turk, I prefer the term “traditional jazz.” It is a broad term that covers all styles of pre-swing jazz including the various revival styles. It’s understood by everyone from the fan to the general public, even by the handful of people who prefer the term Dixieland.

“Traditional” implies the respect that musicians bring to the music and indicates that they don’t intend to stray beyond certain musical boundaries. It is also broad enough to apply to anyone playing within those boundaries. Traditional jazz seems to be understood by everyone to not indicate the musical vocabularies introduced by swing or any later forms of jazz. The dance community uses this terminology to differentiate bands. It’s an easy and useful point of reference for dancers who may prefer one style over another. As more traditional jazz festivals partner with swing dance events, a lingua franca is useful.

Someone may tell you that Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, or Nina Simone sang traditional jazz. That person probably doesn’t listen to those fine ladies as much as they’d like to think they do. They could just as easily say they like Dixieland and name Dizzy Gillespie who they also don’t listen to.

The term “hot jazz” is another good substitute for people who don’t want to say “Dixie”. My only concern with it is that most casual fans don’t understand the concept of playing “hot” and will assume everything is fast, fast, fast. Traditional jazz is much more than good time music, it’s a living art. The term “hot jazz” has its uses, particularly in advertising, “early jazz” also works in most contexts.

For non-modern jazz as a whole, “classic” works and has some salience. “Classic” is big. Big enough to include everything from King Oliver to cabaret singing to John Coltrane. It has boundaries inclusive of bop and stopping where things get too much for the average listener.

In Summary

I won’t hold it against anyone for using the term “Dixieland.” I encourage anyone else who, like me, finds it troubling to give anyone using it the benefit of the doubt. As with an older person who innocently says “colored” because it was a neutral enough term in their time it is vitally important that we not disrespect people who have given us so much. Jazz is passed on hand to hand, and almost every young trad band today has members who learned directly by playing with people who at some point called it “Dixie.” Very often their bands owe much more to that style of play than they care to realize.

Go ahead and use the term if you insist, and don’t feel embarrassed as you do so. But understand that fewer and fewer people are going to know what you mean, and some may feel instinctively offended, even if they can’t explain why. Please don’t apply it to anyone who doesn’t want it applied to them.

I’ll still be using “Dixieland jazz” where a band identifies by the term either historically or in the present. The reality of its use over 85 years is not going to go away. Dixieland is a helpful descriptive shorthand. Using it in the proper context is preferable to trying to talk around the word.

Stripping away ahistorical associations with the minstrel era and the “music for white guys” image that traditional jazz picked up during the revival is vital for its continued growth and preservation. Retiring the inaccurate, and racially charged D-word will only be a start.

We need to encourage our young people, particularly African American children, to embrace the early jazz musicians as the source of pride they should be. These were people who despite adversity created music that continues to inspire. Enough time has passed since those mid-century missteps that we may start having success doing so.

Reader Responses to: Reconsidering “Dixieland Jazz” How the Name has Harmed the Music’

While I argue above for the discontinuation of using the word Dixieland in a jazz context. I have more nuanced feelings about removing standards in the repertoire because they once had minstrel associations. Please see: Dinah, Keep Blowing Your Horn

Joe Bebco is the Associate Editor of The Syncopated Times and Webmaster of SyncopatedTimes.com