Note: some of these letters were in reply to Is the term Dixieland Jazz Racist?, which was printed in September 2019. Most of them are in reply to Reconsidering “Dixieland Jazz”: How The Name Has Harmed The Music which appeared in October 2019. Further replies received on this topic may be added here but they are unlikely to appear in print.

Charles Suhor:

I appreciated Joe Bebco’s thoughtful views on the term “Dixieland Jazz” and the exchanges that followed. I totally agree with Bebco that musicians who don’t want that tag applied their music should be respected. I fact, no practitioners of any art should be saddled with labels that they don’t approve of.

But we’ve been dealt a confusing, stilted hand as we inherited the “Dixieland Jazz” term, with its racist associations. I was born in New Orleans in 1935 and grew up when the term was simply functional–the coin-of-the realm name referring to a style that arose after early New Orleans jazz. To oversimplify, musicians had moved away from rapid vibrato and ricky-tick phrasing of non-jazz (and some early jazz) musicians. The “Dixieland” style was being wonderfully realized in New Orleans, Chicago, New York, and elsewhere by Sharkey Bonano, the Bobcats, Art Hodes, Eddie Condon units, Ben Pollack, Armstrong’s All-Stars, and innumerable other groups.

The music wasn’t “revivalist” in intent or style but a fairly recent evolutionary development. The terms“revivalist” and “trad” didn’t even appear until around the mid-forties, mainly through the British bands that were enamored of Oliver, Bunk, and Bechet–similar to West Coast conscious revivalists like Bob Scobey and Turk Murphy. I had a few of their records, but Dixieland players and many critics saw the revivalists as reactionary or outright corny. (Bobby Hackett remarked, “It’s certainly funny hearing those youngsters trying to play like old men.”) A rash of bands with tubas and banjos in the rhythm section, varying hugely in quality, emerged in following decades and continues today. A more inventive revivalism flowered only in recent years with groups like Tuba Skinny.

The “Dixieland” term came to be increasingly (and justifiably) regarded as offensive. I’d welcome a new term, but “traditional jazz,” “classic jazz,” “hot jazz,” “New Orleans jazz,” and “Chicago jazz” are either too general or limiting, or they already have other popular meanings. Any new term would have to gain a foothold in the jazz community and ultimately, in general usage.

I believe that my choice, “post-foundational/pre-swing jazz” gets to it, but it’s a mouthful.

As a historian, I’ve had to deal with the fact that the “Dixieland” term is embedded in the literature of jazz. I dealt at length with the problem in my 2001 book, Jazz in New Orleans–The PostWar Years Through 1970. I didn’t presume to settle the matter but set out operational definitions so that readers would know what I was talking about when I discussed kinds of jazz. I acknowledged the “Dixieland” dilemma but had no other term to communicate the fundamentally identifiable sub-genre which, through accidents of history, came to be called “Dixieland Jazz.” I’ll continue to use the term with a short explanation of the historical context, or when a musician or band self-describes with it.

Paige VanVorst:

Interesting article- I’ve been intensely following this music for sixty years and haven’t spoken the D word in 59 years- all the records I bought that first year were by the Dukes and after that first year I started listening to more serious music. Never used it in writing except when I wrote an article about the Dukes a few years ago. Never thought of the name as racist- I just thought of it as referring to music I’d outgrown, though there is a lot of evidence that people in the South emphasized certain things as part of the heritage they lost when they got beat. There are certainly enough old songs glamorizing magnolias and the like. I’m happy with traditional jazz and don’t miss dixieland.

Reverand Bob Throne:

I’m a new subscriber and I am very pleased with things so far. I came by way of Tuba Skinny, and have stuck up a trans-Atlantic friendship with Ivan Huke. I was able to help bring Tuba Skinny to Philadelphia August 30 and it was a smashing success; 450 deliriously happy fans and dancers.

However… I got an email a couple of weeks ago with some sort of archive of prior articles. I was about to send you a letter of some concern because the first article was, well, essentially defending racist language.*

I can’t tell you how much I appreciated your “Reconsidering Dixieland”. I have a mixed race family (I’m the only WASP), have served a long term, well integrated congregation, and I can tell you that ‘Dixie’ and variants ARE hurtful, whether uttered out of ignorance or malice. Like the Confederate flag, they celebrate an age of racism right through Jim Crow and into today’s use of code words to celebrate Whiteness. My kids and grand-kids are being hurt today by overt racism, and equally by ignorant White assumptions that excuse and perpetuate a silent but all too real attitude of superiority. I see how careful you are with language so as to avoid losing customers… keep writing so as to educate and affirm our better angels. Many thanks for hearing me out and your fine work.

*[He is referring to Texas Shout #1 Dixieland from 1989, the popular Texas Shout column was republished on the website and was featured to our email list. In Texas Shout #55 “Traditional”, and several others, Tex Wyndham further lays out his reasons for preferring the term “Dixieland” but he had never heard an argument that the term was offensive so he never touches on that topic.]

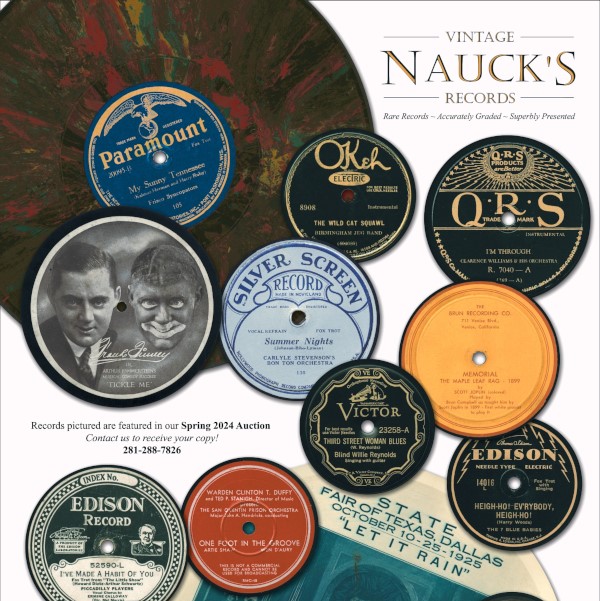

Kurt Nauck:

I, for one, will not allow politically correct interests to redefine my lexicon. Dixieland jazz is Dixieland jazz. A manhole cover is a manhole cover. People today choose to get offended over anything and everything. Today it’s dixieland, tomorrow they’ll be demanding we dynamite the Stone Mountain Memorial.

We learn from the past, but we should never erase it. No one ever used the term Dixieland with the intent to be either racist or offensive, and plenty of black men played it as well. This is a political agenda, pure and simple. These folks need to grow a pair and learn to live in a pluralistic society where we mutually respect one another.

Molly Ryan:

We need black musicians to want to play this music. We need black people to feel included. If the OKOM crowd want this music to die with them, that is not something we should support. All my opinions are formed based on speaking with black musicians. They are not assumptions. Black people feel more comfortable participating when they see other black people performing this music.

You are fighting the good fight and doing something remarkable by not only keeping this paper going, but continually growing the content and audience. We applaud and appreciate you. Dixieland is no longer an acceptable term. It hasn’t been for a long time, but many of the trad fans don’t know that. If an argument is created that we can’t remove this word because eventually we’ll need to remove all words associated with this style of music and the era it was born in, I don’t buy it. That won’t happen. Aside from hokum and certain lyrics we no longer sing what other terms are now verboten? It is easier to remove a word or phrase from your vocabulary than to argue to death why people shouldn’t be offended. If I never hear “The world is too politically correct. You need to get over it. I’ll say what I want” ever again, I’ll be content.

I’d like to open up a trad Jazz society paper or magazine from one of our subscriptions and see more diversity. It does not take an open mind to be sensitive and constantly strive to create the best work we can. It just takes empathy. I don’t like problems. I like solutions. If the paper needs more eyeballs during the editing process to help put out as inclusive a paper as possible, I’d love to help. I know many others would as well.

Bob Kemper:

An interesting essay and one in which I agree wholly. I play trumpet in the traditional jazz style, as well as swing and be-bop. Sometimes I will say New Orleans style jazz with people who have no idea what tradition jazz means. But I haven’t used the “D” word in a very long time.

Years ago I played with a band every Tuesday night at Shakey’s Pizza. We had to wear red and white stripped vests and a straw boater. I was embarrassed. It was making a mockery of the music and the people who created that music. It’s like seeing fabulous Bluegrass musicians who had to dress like hillbillies or hayseeds on TV.

To me early jazz is another form of American folk music. It’s what people did with family and friends when they got off work for fun and relaxation. It’s the same with Appalachian folk music which became Bluegrass. People would gather on someone’s front porch on a hot day after a hard day’s work have fun expressing themselves. Bill Monroe told me in the early days of his band they would do two shows on the same day. One show in the white section of town and another show in the black section of town… the playlists were identical and the songs received equal enthusiasm.

I heard B.B. King saw that if it wasn’t for young white kids he would not have had a career. I listen to Hunter and Jenkins and think how much fun this couple was having. Yet today they would be considered as laughable and not in a good way.

I’ve played trumpet and guitar in black bands and have been told that I had no business playing “our music.” There is no ‘our music.’ All music is an amalgam. Where would jazz be if not for the French marching bands in New Orleans, the adoption of European instruments and European music notation? Prejudice in music always comes as a surprise to me.

Scott Yanow:

Through the years, quite a few musicians have denied that they play Dixieland even though their music says otherwise. The term was overused in the 1950s when, due to the popularity of the style, an awful lot of amateur and sometimes corny musicians attached themselves to the movement, emphasizing fast tempos and too many notes (sometimes played out of tune) over lyricism and making a coherent statement. As our esteemed editor Andy Senior related in a recent editorial, some contemporary listeners think of Dixieland as being a term related to racism even though plenty of both African-American and white musicians have used the title in their band names through the years.

I have a different opinion. Dixieland is an honorable form of music when played at a high level. In fact, due to its fairly simple harmonies, it is the happiest of all musical styles. Because several other approaches share some of its musical qualities, it does get confusing knowing what is Dixieland and what isn’t. Much of the music of the 1920s is not Dixieland and is best called Classic Jazz. Neither is much of the ensemble-oriented New Orleans jazz of Bunk Johnson and George Lewis, or the King Oliver-inspired San Francisco jazz of Lu Watters and Turk Murphy (who preferred to call his music “traditional jazz”) despite similarities.

While the first jazz group to record was the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, the Dixieland term was originally used in jazz to announce that the music was from the South. The style of Dixieland was actually formalized in the 1930s by small ensembles (including those led by Eddie Condon) as a joyful alternative to the music of larger arranged orchestras. Typically its performances, which usually have the feel of a spontaneous jam session even if the musicians know beforehand the road map of each song, start out with an ensemble chorus or two, feature individual solos, and end up with more ensembles that are improvised rather than tightly arranged.

Although nearly any song can be played in the style, by the late 1930s most Dixieland groups were playing a similar repertoire that is not that different than what is performed by these type of groups today. The roles of the trumpet (taking care of the melody), clarinet (creating countermelodies), and trombone (playing percussive harmonies) in the ensembles were set early on although sometimes a saxophonist or two also joins in with their own melodic variations.

While no creative musician should be limited in their playing by a term or by fans’ expectations, there is no shame in playing Dixieland, or in using that name. After all, I am one of many who love Dixieland.

Wayne Pauli:

I read your recent boring article in the last Rag, by Joe Bebco, about one of my favorite words, DIXIELAND, and I feel I must respond.

First of all it was the longest diatribe of verbal bs that I have ever read in your Rag going back to enjoying years of reading The American Rag long before you took over.

Why are some people trying to change history?

In the USA, apparently, if you tear down a statue honoring history at the time, which you people tend to do, you make it false, like it didn’t happen. We see all this non-historical crap north of the border. Tear it down. It was not history. Shake your head.

If you pretend that black musicians were not taken advantage of – again – shake your head. Of course they were. But where did some of this terrific music come from? The blacks. The slaves. Oh, I’m sorry, I guess you are not supposed to say “blacks”. When my sons grew up, and were involved in sports and education, our home was a welcoming place for their black friends, they called my wife “Mom”. Why is it that it is so important to make this totally immoral world all of a sudden perfect. It won’t happen.

I grew up in Canada. Our country did not bring slaves to our country, and neither did your generation. BUT, please try to tell me where music called DIXIELAND began.

Yes, I’ve read and heard all the stories about racism in music, taking advantage of the blacks (of whom I have many friends), blackface, the “white” jazz bands, etc. I have seen several minstrel shows years ago and you know what. I never perceived a problem between the entertainers (black) and the audience.

WHY, WHY do some people want to change history? Does it not sound right? Do you not enjoy it? Do you have a mission to change what was? It can’t happen. What was, was. Live with it. Enjoy the music! Shake your head jazz fans, it is still the best music in the world. Enjoy it. Don’t analyze it.

DIXIELAND music is the best.

Steve Proviser:

An excellent piece, which lays out the landscape very well and fairly. I can’t imagine any of the older demographic being alienated by it.

Ray Boyce:

The Dixieland pros and cons make for fascinating perusal. I choose not to address the validity of either camps’ opinions. Rather I harken back to what a very wise man inquired of me in conversation seven decades ago “What is less hateful than music?” Call New Orleans bred “hot” dance music what you prefer but please in the name of your favorite diety do not denigrate its century old nomenclature because of political considerations about the area whence it originated. Arguments will doubtless continue, without bloodshed I trust, but may the discussions ultimately allow musicians and fans freedom of reference to what they’re performing and (hopefully) appreciating.

Name Withheld:

I’ve been aware of this debate for a while and am extremely glad you brought it to the forefront of debate and discussion. Within our jazz society, unless a band calls themselves Dixieland, we don’t use that term to describe them or their music.

For me, until I hear a group of African American musicians say they are pleased nowadays for their music and musical style to be called Dixieland, I don’t believe it’s a term we should use to describe their music.

Jon Wilkman:

I’m a suscriber, documentary filmmaker, and author and wanted to write to say how much I enjoyed your thoughtful piece about the impact of the term “Dixieland” on perceptions of traditional jazz. As a longtime fan of the music and nonacademic historian, I’m in the process of researching a new book about the subject in its contentious historical context, then and now, tentatively entitled Hot Jazz Remix, and am finding Syncopated Times invaluable.

David Limburg:

I wanted to send you a personal note of thanks and congratulations for your very thoughtful, well-researched and heartfelt article. You addressed all the major issues with humility and sensitivity, and made, in my opinion, a very reasonable assessment as to why this particular idiom of jazz is not more widely accepted, especially among African-Americans. My hat is off to you. I hope you have more articles like this in you. I hope it is well-received by the general readership.

Dean Norman:

I have an LP record that I play occasionally that has Louis Armstrong playing with the Dukes of D________. Louis and Frank Assunto take turns playing solos, and I can’t tell for sure which one is playing on which solo. I don’t care which one is playing. They both sound great.

I attended a concert in Kansas City Missouri in the 1950s when The Dukes of D_____ played the first set, and Louis and his All Stars played the rest. After the Dukes of D_____ played, I wondered how can Louis top this? Well, he did top it, mostly because he sang several duets with Velma Middleton. When she sang “All of Me”, Louis rolled his eyes and the audience loved it. “Baby it’s Cold Outside” was another hit of the evening. Yes, Louis played some solos that were fantastic, but Frank performed some great licks, too. It was a wonderful concert.

I never thought about what kind of music they were playing. I just enjoyed it. Much later I heard a reporter interview Louis Armstrong. Or maybe I read the interview. But I think I heard it, because in my memory I hear Louis speaking in his happy, friendly, gravelly voice. The reporter said something like, “What kind of music do you play? Is it jazz, or swing, or pop, or what?”

Louis said, “I don’t believe in all this analyzing and classifying. There’s only two kids of music, Good music and bad music. I only play GOOD music.”

Maybe we could solve the problem of what to call our music…Traditional Jazz, Early Jazz, New Orleans Jazz, D_______…by just dropping all those names, and say, “It is Good Music”.

Bob Storms:

I thoroughly enjoyed Joe Bebco’s “Reconsidering Dixieland” article in the October issue of the Syncopated Times. While he has a problem with the term “Dixieland”, I have a different problem dealing with the “Traditional” label.

I currently lead a band called “The Bellingham Dixieland All Stars” and we are celebrating our tenth year together this year. The “All Star” portion of our band’s name refers to six of our players who have played on the Trad. circuit for over 20 years in various festival bands. My previous band, the “Bathtub Gin Party Band” played the west coast festivals for nearly twenty years.

As to the “problem” I referred to earlier, there is a feature of Traditional Jazz music that bothers me – new music can’t be traditional if it is new. The local Bellingham Traditional Jazz society features my band yearly, and is not surprised to hear new Dixieland-sounding tunes and songs every time we perform. Yet, I can’t refer to my band’s new music as Trad. even though it sounds like Trad, or Dixieland.

I’m also feel uncomfortable with the term Dixieland in our band’s moniker and want to change it, but I’m not going back to my previous band’s name. I have repeatedly asked a local black drummer to perform with the band, and he always refuses. He played in my swing band, “Variety” for several years without a problem.

As a composer, I have personally written over two hundred “Dixieland” tunes and songs, and my band performs many of them annually in a concert series I call Jazz Celebration. That concert has become a staple of jazz music in Bellingham, Washington, over the ten years of its existence. It is all new music – two hours of it, actually.

So, I’m dealing with both “Dixieland”, and “Traditional” jazz terminology. I’m considering “Hot Jazz” as a substitute for “Dixieland”, as was mentioned in the November issue of the Syncopated Times. I’m still searching for an answer to referring to my music as “Traditional”. I’m open for suggestions. (Tips are encouraged)

Rick Campbell:

Your editorial on the term “Dixieland” was right on. I have been lobbying the Portland Dixieland Jazz Society to change its name back to Traditional Jazz Society, with no success. In my attempts to reach out to high school and college music educators, I learned that the word “Dixieland” is a definite turn-off.

If we are going to reach a younger generation, we had better brand ourselves with terms that are acceptable to our target audience. Otherwise, it is like going to bat with two strikes against you. That is simply pragmatic marketing. But like you, I hate what the PC crowd is doing to our language.

For me, the irony is that during the “Jazz Age” of the 1920s, young women in flapper dresses where liberated—drinking, smoking, discarding their girdles, rolling down their hose. And in the honky-tonks, there was considerable mixing of the races. I’ve always thought that hedonistic spirit was suited to our modern era, so perhaps I’m too old to understand. Excellent issue as always!

From Facebook

Adam Arredondo:

Thanks for this article. I think it is the duty of everyone involved in the business of playing pre-swing jazz to be engaged with these topics. Articles like this and conversation with people with a variety of perspectives are key here. The one bit of criticism I would like to respectfully offer is to be a little more careful with absolutes and blanket statements.

Paul Morris:

A few years ago during a performance at Preservation Hall in NOLA, I heard the drummer Shannon Powell talk briefly about this during a performance. He said that nowhere within the Hall would you find the word “Dixieland.” That it was a racially charged word and no longer represented the music we were hearing.

Yet there are many festivals across the country that use the “D” word in the titles, Facebook pages that self-identify with the D word and performing groups that still use the D word in their names. Time to begin to change those things.

Since the 1960s, America has made different choices in choosing the racially charged words we use. We can go forward and begin to use our word choices in a more thoughtful way.

Jeff Kreis:

I agree with most of this. I think the author was a little too careful not to hurt anyone’s feelings, but I felt the reasons behind dropping the term “Dixieland” are well laid out. As a practitioner of traditional jazz in New Orleans, continuing to use racially charged language is hurtful to a lot of people I care about. I don’t really care if you’re gonna have to change the name of your jazz society

Lucas Ferrari:

I stopped using the term “Dixieland” because it’s associated with a certain way to play jazz that I don’t like, and that’s corny loud post 1950s pseudo traditional jazz.

Steve Boisen:

The band I’m in (which is racially diverse) stopped using the term simply because it fell out of fashion, although it’s still in the text of our website.

The following comment was from a related Facebook discussion about the term “Cakewalk”.

Jason Winikoff:

I used to live and gig in New Orleans for a while. When I was there I occasionally played in a band called “Cakewalk.” I never thought twice about the name but eventually I started hearing complaints about the name from some locals and other African Americans who came into contact with the group. They told me to educate myself and look up the history – then I’d understand why they don’t like the name. So I did. Eventually the band changed its name, made a public apology, and everyone happily moved on.

“Cakewalkin Babies” is a great song. For sure. There are also beautiful trad songs that glorify plantation life, that are extremely misogynistic, or quite racist. I’ve been in trad groups in New Orleans with black band members and they have refused to play certain songs because of these lyrics or titles. I’m not necessarily saying that we need to stop listening to those songs. But maybe, just maybe, we don’t have to name bands after them. There is so much more to appreciating this music than just liking the songs, artists, and knowing the history. We need to pay attention to the SOCIAL history as well. We really need to understand that this amazing music was a product of a time that didn’t treat everyone equally. And we really need to listen to everyone’s voices should they speak up about issues with it.

I know y’all all probably hate all things political correct. Fine. But if y’all find absolutely no issue with naming a band after a music tradition that some black New Orleanians have an issue with then I’m not sure how much you fully respect all things “Dixieland Jazz.” I am not trying to start any argument at all. In fact I was shocked that I was the only one on this “side.” But damn y’all, being told to “get real” or “it’s a great song, don’t change anything” was quite disheartening.