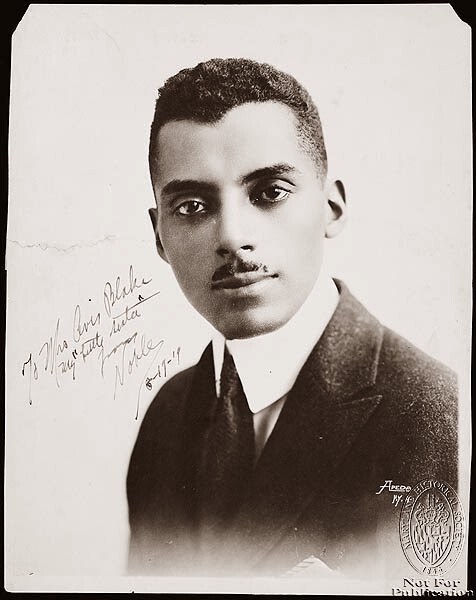

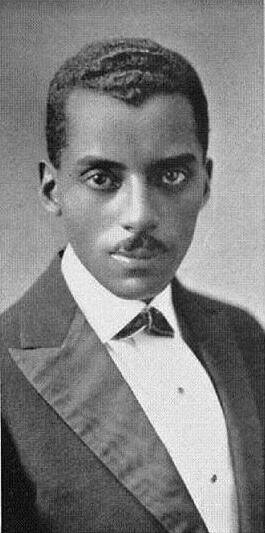

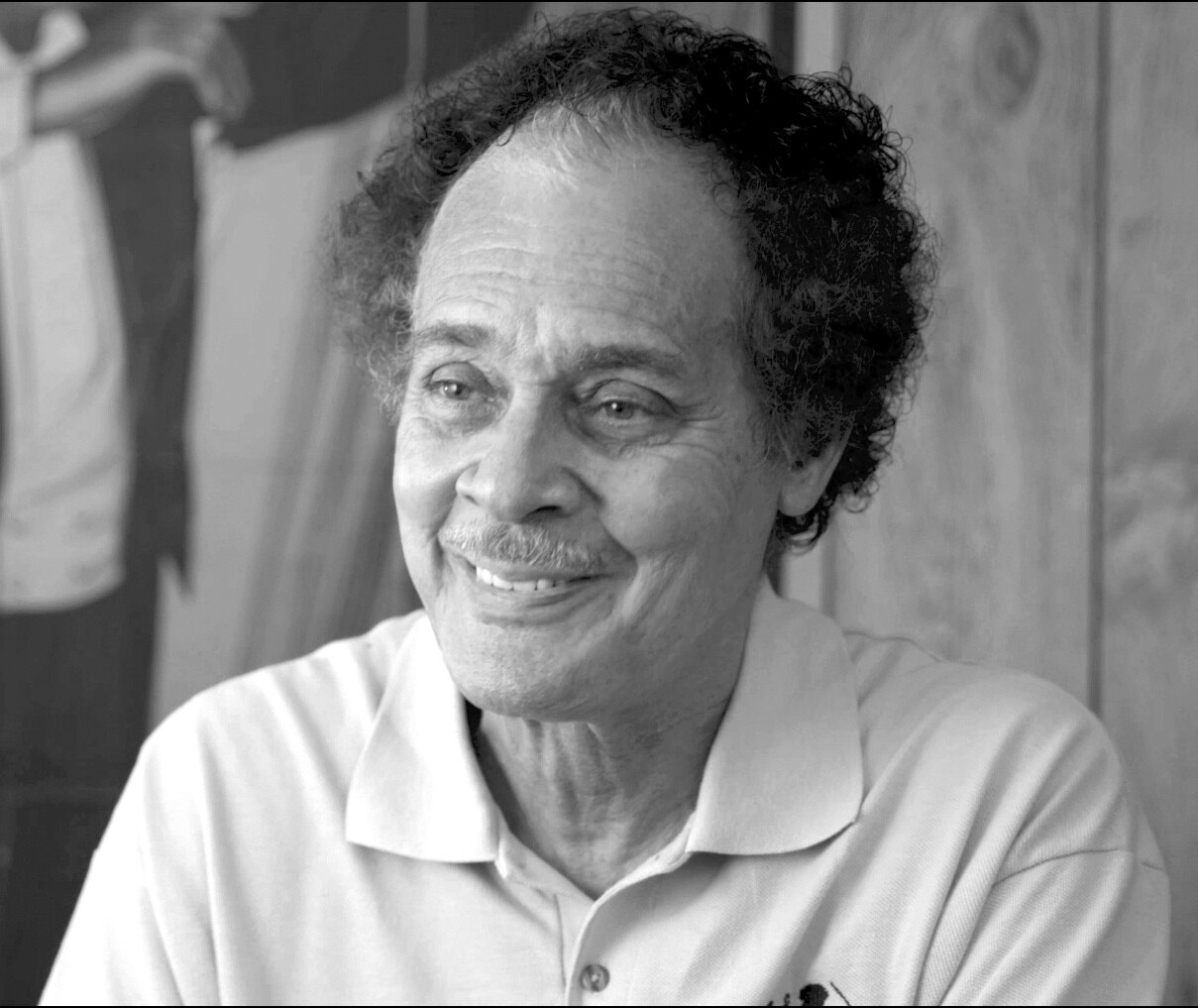

Singer-lyricist-bandleader-entertainer, Noble Sissle occupies an unusual place in the world of ragtime, jazz and show business. He was one of the best-known musicians of the early to mid 20th century, intimately involved with James Reese Europe and partnered with the great pianist-songwriter Eubie Blake. Sissle was peripatetic—East Coast, West Coast, Europe. He was not easily genre-stereotyped and there are gaps in his story, but I had a long conversation with his son Noble Sissle, Jr., (whom I will refer to here as Noble, Jr.), read other documentation and have put together what I think is a pretty fair overview of his impressive life.

Singer-lyricist-bandleader-entertainer, Noble Sissle occupies an unusual place in the world of ragtime, jazz and show business. He was one of the best-known musicians of the early to mid 20th century, intimately involved with James Reese Europe and partnered with the great pianist-songwriter Eubie Blake. Sissle was peripatetic—East Coast, West Coast, Europe. He was not easily genre-stereotyped and there are gaps in his story, but I had a long conversation with his son Noble Sissle, Jr., (whom I will refer to here as Noble, Jr.), read other documentation and have put together what I think is a pretty fair overview of his impressive life.

Sissle was born in 1889, to Rev. George A. Sissle, a Pastor in the AM&E Zion church and Martha Angeline, a school-teacher and juvenile probation officer. His dad’s first wife had died, leaving 3 children 10, 11, and 12 years older than Noble and for a long time he didn’t know they were step-brothers and step-sisters. Near the end of his life, he would live with a nephew that was more or less the same age as him.

The family lived in Indianapolis when he was born, but moved to Cleveland. Sissle’s talent as a singer was recognized early and he began performing in church settings by the time he was five or six years old. He attended the integrated Central High School where he was in the high school chorus and a mixed-race male vocal quartet. An interesting story: In 1908, when Sissle and the rest of the football team went to a movie, as the only black person, the theater made him sit in the balcony. His teammates persuaded him to file a suit. He did, and with two NAACP lawyers won and collected $250. The NAACP was formally founded in 1909, so I assume this was one of the very first cases they handled.

His father had been sick—he died in 1913—and Noble was in and out of school as he went out on the road with Edward Thomas’ Male Quartet and Hann’s Jubilee Singers to help support his family. According to Noble, Jr., he didn’t have to experience the racist problems that faced many black performers on such tours as there was a network in the AM&E church. Through this network, members of the group were housed by families affiliated with a church, and would then sing at the church.

Sissle was a guy with a big personality. He was that rare creature-a teetotaler who was also the life of the party. He was the “yell-master” of the Rooter’s Club at high school and would rouse the crowd through his megaphone. Years later, in 1914 at Butler University, he said he would “dance around among them on the floor with my yell-master’s megaphone and whoop up the dancers.” As you watch the films that Sissle appears in through the decades, you can see that he kept the verve that made him a popular, entertainer, apart from any musical skills he had.

Sissle was a guy with a big personality. He was that rare creature-a teetotaler who was also the life of the party. He was the “yell-master” of the Rooter’s Club at high school and would rouse the crowd through his megaphone. Years later, in 1914 at Butler University, he said he would “dance around among them on the floor with my yell-master’s megaphone and whoop up the dancers.” As you watch the films that Sissle appears in through the decades, you can see that he kept the verve that made him a popular, entertainer, apart from any musical skills he had.

Sissle was working at the Severin Hotel in Indianapolis in 1914 when he was asked by the manager to organize an orchestra, and he did. In ten days, he went from being a waiter to leading, singing, and pretending to play the banjolin with a twelve-piece orchestra. Noble, Jr. says that his dad’s repertoire was basically church music, but that if he had a request to sing a popular song, he would learn it.

That spring he was hired as vocalist for “Joe Porter’s Serenaders” at River View Park in Baltimore. Eubie Blake was playing piano with that group. For some reason, Blake had noticed Sissle’s name on a piece of sheet music of “cheers” Sissle had written for athletic teams at Butler University and some poems he’d written that had been set to music. Blake asked Sissle if he was a lyricist and their long songwriting collaboration began.

Their first tune was “It’s All Your Fault,” and much to Blake’s surprise—less to Sissle’s—they were able to present the song to Sophie Tucker backstage when she was performing at the Maryland Theater in Baltimore. Rain had ruined the sheet music that Blake had written, but he remembered the song and Sissle had the words written on a separate sheet, so they were able to perform the song. Tucker was impressed and bought it.

Sissle’s transition to New York is hard to pin down. Noble, Jr. said he knew little about it and there is little in the written record. Apparently, he and Blake had both done some gigging in NYC and both knew about James Reese Europe and the Clef Club. In December 1915, Sissle was working in Palm Beach with Bob Young’s sextet at a Red Cross Benefit and met a women there named Mary Brown Warburton who knew James Reese Europe and he asked her to write a letter of introduction to Europe, which she did. E.F. Albee brought the Benefit show to New York and Bob Young’s group with Sissle was the first black group to play the Palace in formal dress and without “corking up” in blackface.

After the “Palm Beach Week Show” ended, Sissle presented himself to Europe, who said he’d already heard of him and was glad to have him aboard. Sissle wanted to get Eubie Blake into Europe’s orbit, but Europe said he’d already seen him play and had been trying to get him into his organization. Sissle sent Blake a telegram to come up to New York and Blake balked, talking about how cold it was and why should he come up to that unfriendly city. Sissle responded: “for a steady paycheck” and Noble, Jr. says: “He was up in New York within two weeks.”

Europe had put the Clef Club together in 1910, but by 1913 Noble, Jr. says, he was tired of dealing with the in-fighting and jealousy in the Clef Club and that’s why he took a few people and started the Tempo Club. That being the case, when Europe met Sissle in 1915 and learned that Sissle had a good business sense, he became his business partner not in the Clef club, but in the Tempo Club.

Noble, Jr. says that Europe always had at least five bands going every night and always visited each group to make sure everything was running smoothly. He’d come on stage make a short announcement, start the band back up and leave the stage, Noble Jr. says, “accompanied by two white women.” Sometimes Europe would put Sissle in charge of one band. Other times, he’d take Sissle with him on his “rounds.” Eubie Blake was one of about 20 pianists that Europe kept in circulation and Noble, Jr. says that if Sissle and Blake worked together at this time, it would have been by chance. However, one source says that Sissle and Blake reunited at the Bridge Water Inn in New Jersey and worked as a duo at weddings, parties and other events for high-end James Europe clients.

There was clearly a bond between Europe, Sissle, and Blake and they often talked together about future plans. Europe wanted to put a symphonic orchestra together and they all had a vague idea of putting a legitimate show together for Broadway. This conversation continued for years.

In another conversation that had gone on for years, the black community had been pressuring the governor of New York to get a National Guard armory in Harlem. There were many cities with black regiments, but not New York. So, the 15th Regiment, nicknamed the Harlem Rattlers was formed, but it was small. In 1916, Col. Haywood, who was in charge of the regiment, asked Europe to help him by starting a regimental band. Europe agreed, but said he was joining in order to fight—not to lead the band.

So, Europe was signed on as a Second Lieutenant in the machine gun company of the regiment. When he told Sissle he’d joined up, Sissle was very surprised, but Europe explained why he joined and why he thought Sissle should enlist. Europe said it would help entrench Sissle in the New York community to which he was a relative newcomer, and that it was a chance “for the development of the negro manhood of Harlem.” He also said he needed Sissle there to help start and run the band. The top rank in a band is a Sergeant and is called the Drum Major and that’s how Sissle entered the army.

Europe was nervous about the prospects of putting together a band of decent caliber, and convinced the army to give him $10,000 so he could get the players he needed. Europe left Sissle in New York to advertise for musicians, while he installed two bands in hotels in Palm Beach. Europe lacked reed players and thought he could find them in Puerto Rico, so he returned to NYC, then boarded a boat to Puerto Rico, where he recruited 15 musicians.

The two all-black divisions in the U.S. Army were the 92nd and 93rd, which was now going to include the 15th. For a while, the band played parties and drove through Harlem playing, trying to get people to enlist. Then in October, 1917, the regiment was sent to Spartanburg, South Carolina, to train at Camp Wadsworth. There had been racial incidents at other camps across the country and tension was high everywhere. As Sissle recounts it, during the second week they were there, Europe asked him to go into the lobby of a hotel to get the New York papers. He was reluctant, but a local resident told him that yes, it was a white hotel, but that colored were allowed to go to the newsstand. Sissle went in and bought the papers, but as he was leaving, he was grabbed roughly by the collar and insulted by a white soldier. He left as quickly as he could and was kicked several times on his way out the door.

Sissle says he hadn’t meant to say anything about it, but he recounts that “a Jewish boy from New York” wanted to lead some soldiers into the hotel lobby on a mission of revenge. A hundred or so soldiers had gathered outside the hotel and Europe told them to wait while he looked into the situation. While Europe was investigating, the Military police arrived and several white officers in the hotel commented on how soldierly both Europe and Sissle had behaved.

Europe had managed to diffuse the situation, but the Army could see trouble looming. They locked down the regiment and within a few days, the 15th was on a train back to New York. Despite their lack of training, it was decided to send them to the war. They left on a rickety ship called the Pocohantas.

Trumpeter and conductor Eugene Mikel had joined the band in New York and Europe had made him Bandmaster and Assistant Conductor. Frank Bebroite, cornet soloist, assisted Mikel, while Sissle was the vocalist and was involved in logistics. Soon after their arrival in France, the band played the ”Marseillaise” with a ragtime tinge and, at first, the French soldiers didn’t even recognize it. Finally they did and seemed to greatly enjoy this version of their national anthem. The French officers noticed that the band always galvanized a lot of patriotic energy and asked the regimental commander of the 15th to get the band out to different locations. So, they started to tour hospitals and other areas and were then officially assigned to Aix-Les-Bains.

Sissle, Jr says that probably every other regimental black band was as good, but this one got there first. The others were still training and wouldn’t get there until April, and these guys were already established in Europe. Sissle, Jr. says the other bands pulled in musicians from all over and thinks that Sidney Bechet probably played with the band out of Chicago.

The rest of the division had been doing grunt work—working on a dam with picks and shovels (although not Sissle, who’d temporarily been laid low with a case of the mumps). The French, because of their African colonial history, were used to fighting with black men and they said to the U.S. Army: you have 2,500 black soldiers you’re not doing anything with, so can we borrow the 369th from Harlem? The soldiers exchanged part of their uniforms for French uniforms and were sent off to Heirpont for more training.

The band rejoined the regiment and three weeks later, played them off to the trenches. There, the regiment fought for 191 straight days. The French called them the “Men of Bronze” and the Germans called them the “Hellfighters.” That’s the name that stuck.

The war ended in November, but they didn’t come back until February 17, 1919. They hadn’t had a parade when they left, but they would have one now. Most parades were down 5th Ave, but this one was up, as they were headed toward Harlem. When the 2,000 black soldiers, led by the 45-member band, reached 110th St. and played “Who’s Been There While I’ve Been Gone,” the crowd closed in so tightly that it became more like a street party than a parade.

Europe realized the Hellfighters had a big name and reputation and took the “Harlem Hellfighters’ Band” into the studio to record 24 sides for Pathe Records in 1919. Sissle sang on six. If you compare these to the recordings Europe made in 1913, there’s less ensemble work and more individual effects coming from the brass section and the clarinet.

As “Jim Europe’s 369th Infantry Jazz Band,” 85 musicians, still in uniform, performed in the Manhattan Opera House and started out on a 10-week tour. Steve and Herbert Wright were drummers in the group and while they were in Boston one of them, Herbert, thought Europe was picking on him unfairly. Sissle tried to defuse the situation, but Wright burst into Europe’s office and in an unlucky stab, pierced Europe’s neck, Europe had already been weakened by a bad flu and the knife wound killed him.

This was a terrible blow to Sissle, who venerated Europe. Promoters wanted to put out a vest-pocket edition of the Hellfighters, but Sissle wasn’t interested. Not long after these events, Sissle married Harriet Toye. He helped to raise Toye’s daughter and together they had two more children.

At that point in 1919, he and Blake decided to form an act they called the “Dixie Duo.” Bookers wanted them to do something more akin to a “coon” act, and they did retain some minstrelsy, but they were intent on doing a tuxedoed, higher-class musical act-the kind of thing they’d been used to doing in the Tempo club gigs. The attention-getter for the act was a performance of “On Patrol in No Man’s Land,” written by Europe after he’d been gassed, with Sissle’s lyrics. During their act, Sissle would sing the tune while he was pretending to crawl through no-man’s land. It was a very successful act on the vaudeville circuit. One measure of their growing reputation was that they were chosen as one of the subjects of a series of “talkies” produced by inventor Lee DeForest in the early ’20s, which premiered in 1923. They have a terrific rapport in this short film.

At the beginning of 1921, Sissle went into the studio with Blake and other musicians associated with James Europe and recorded six tracks released by Emerson records under the name he would continue to use through the 1920’s—Noble Sissle And His Sizzling Syncopators. Some of these records are in the James Europe vein, and some move the Europe template into a stronger jazz, less ragtime feeling. Sissle’s vocals are the centerpiece, and ensemble sections that are lightly ornamented are featured, not instrumental solos.

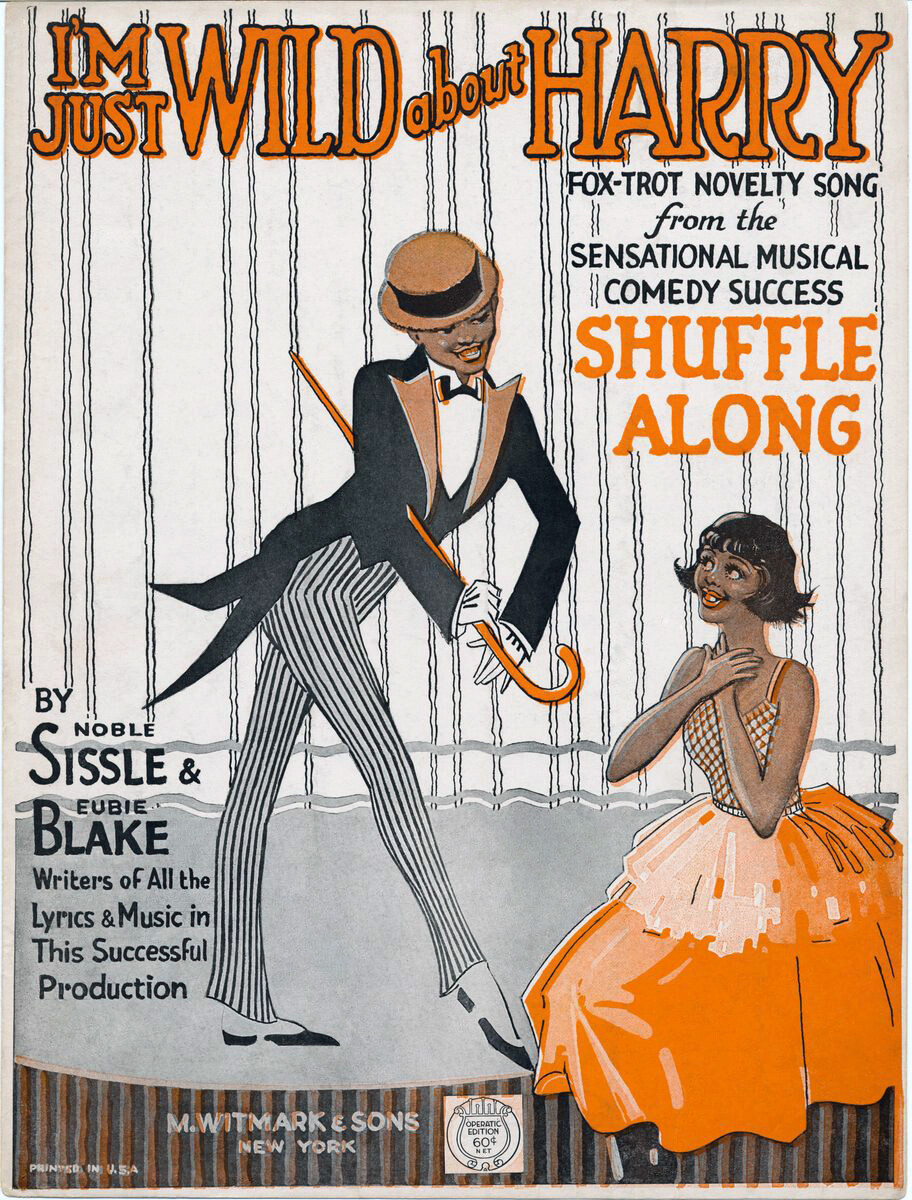

Back when Europe, Blake, and Sissle would talk about producing a show, they discussed how they might find a story to base the show on, and the names of vaudevillians Flourney Miller and Aubrey Lyles came up. Now, years later, in 1919, the “Dixie Duo” was playing an NAACP fundraiser in Philadelphia, also featuring Miller and Lyles. When the show was over, they got together and started to discuss it, but Miller and Lyle didn’t think white folks would go to see a black show, so nothing happened. Then, in 1920, they picked up the conversation again, and by this point, Henry Cort, member of a wealthy white New York theatrical family, had decided to back the show and joined formally as producer. According to the book Jazz Age Jews by Michael Alexander, gambler Nicky Arnstein also put money into the show.

Still, it was a bare-boned production. They sometimes lacked enough money to get to the next city, never mind pay for a hotel room when they got there. In one instance, the owner of a train line who’d seen and loved the show rescued them by paying for their tickets. They were able to get costumes cheaply from a show that had closed. The show was set in Asia, so they wrote “Oriental Blues.” They also had plantation costumes, so they wrote “Bandana Days.” The main character was named Harry. Hence—“I’m Just Wild About Harry.”

Sissle and Blake thought that if they could get to the Howard Theatre, the show would hit and they’d be off running. That didn’t happen, but they did manage to get back to NYC and brought the show into a lecture hall on 63rd street that Blake said, “violated every city ordinance in the book.” He also said: “The tickets are $3.00-that makes us a Broadway show.”

Shuffle Along, a “musical melange,” drawing from the Broadway show tradition, vaudeville and ragtime, opened in 1921 and ran two years. There was so much street traffic generated around the theater that 63rd Street was reestablished as a one-way street. The reason for the show’s success was probably the rhythmic excitement of the songs and dancing, which were very different than what customers were used to seeing on Broadway. The singers, dancers and instrumentalists were all highly trained, but the orchestra performed the arrangements, written by Will Vodery, without music because, as Blake said: “People didn’t believe that black people could read music—they wanted to think that our ability was just natural talent.” Josephine Baker, Florence Mills, and Paul Robeson were all in the cast.

Shuffle Along was the first major production since the George Walker–Bert Williams vehicle Bandanna Land in 1908 to be produced, written and performed entirely by African-Americans. The show toured many cities, generating wide press coverage and generating income from recordings and sheet music sales. Once the show left New York, it toured for three years and was the first black musical to play in white theaters across the United States.

Sissle and Blake then wrote 10 songs in 1923 for the production of Elsie, which never made it out of Chicago. In 1924, their show The Chocolate Dandies, written to showcase Josephine Baker, opened on the road in Rochester soon after the closing of Shuffle on tour. Noble, Jr. says there were 100 people and one horse on a treadmill in the cast. Trumpeter Valaida Snow was also in the show. The Chocolate Dandies closed in 1925 at a loss of $60,000. At that point, their record with shows was one win and two losses, so in 1926 Sissle and Blake decided to return to Europe, where the William Morris Agency provided bookings in England, Scotland and France for the next year.

They were a hit in Europe and Charles Cochran, “the Ziegfield of London,” asked them to write his next show. Blake, however, was not crazy about being over there—he thought the people were kind of phony, and “high-hatting” them so they went back to America and Rodgers and Hart got the Cochran gig.

Back in the US, the “Dixie Duo” performed and Sissle freelanced as a vocalist on recordings for Okeh, Brunswick, and Edison. In 1927, a promoter said he had 16 more weeks for Sissle and Blake in Europe and Sissle signed them up to go back, but without consulting Blake. This caused a lot of bad feelings and, says Noble, Jr.: “They took that as the Sissle and Blake vaudeville act was over.” That did not mean they would never perform or write together again—they did.

The band Sissle had in Europe had an eclectic repertoire and one would not necessarily characterize it as a jazz band. It might also be called a “society” or a “hotel” orchestra. You can hear this on the many recordings he did in London between 1928-1929. Trumpet player Tommy Ladnier provided much of the improvisational punch in the orchestra. Sissle’s band played at formal parties at London embassies and he was a favorite of the Prince of Wales and hobnobbed with the likes of the Rothschilds and Elsa Maxwell.

Cole Porter told him that Fred Waring was leaving an engagement at the Café Les Ambassadeurs in Paris, and they needed an American band. Sissle went to Paris and recruited musicians, including Sidney Bechet, and Noble Sissle’s International Orchestra played all the swanky hotels and nightclubs; the French started calling him the “Ace of Syncopation.” Sissle and his band appeared in a 1931 British Pathétone Weekly filmed at Ciro’s nightclub in London, performing “Little White Lies” and “Happy Feet.”

Sissle was informed that CBS had a 15-minute daily radio slot open, so he decided to return to the US in 1931 and got the slot. Noble, Jr. says that the band was playing in a kind of lilting rhythm and no one really knew that it was a black band.

The publicity from the radio show helped Sissle maintain a high profile, although there are gaps in our knowledge of his career during the 1930s. In 1932, Sissle appeared with Nina Mae McKinney, the Nicholas Brothers, and Eubie Blake in Pie, Pie Blackbird, a Vitaphone short released by Warner Brothers. Then, when Aubrey Lyles died, Sissle and Blake and F.E. Miller wrote Shuffle Along of 1933, but the show didn’t take off (stranding the show’s young pianist, Nat Cole, in L.A.).

Also in 1932, Sissle appeared in a short film with a plot of sorts, That’s The Spirit, in which he conducts, dances, and mugs. Several members of the all-black cast are in blackface.

Sissle continued to play proms and one-nighters and recorded 14 sides for Decca records in 1934, 1936, and 1938 under the names “Noble Sissle Orchestra,” “Noble Sissle’s Swingsters,” and “Noble Sissle and his International Orchestra.” The bands had top-notch personnel. A young Lena Horne made her first recording with Sissle in the 1936 session. In 1934, he was manager of a show produced at the Chicago World’s Fair called O, Sing a New Song. Other participants were Harry Lawrence Freeman, Will Marion Cook, Will Vodery, Lena Horne, and a young choreographer named Katherine Dunham, whose career Sissle helped to launch.

In 1936, Sissle helped to form the Negro Actors Guild of America (NAG) and became its first President. He eventually used it as a platform to establish a Concert Varieties Program for young performers. From 1938 to 1942, Sissle and his band held down a job at “Billy Rose’s Diamond Horseshoe” and he returned there after the war, in 1945.

In the late 1930’s (Noble, Jr. thinks 1938) Sissle got a divorce from his first wife Harriet. According to Noble, Jr. his dad was a real straight arrow and her drinking had become a problem. Around 1940, Sissle started taking in shows at the Cotton Club—he was famous enough to get in despite the color line at the club. There he met his next wife Ethel Watkins, a showgirl at the club. They married in 1942 and quickly started a family. When Noble, Jr was born in 1942, his dad was 52 and Ethel was 26.

At the beginning of WWII, Sissle was an early participant in the formation of the United Service Organizations (USO), and a Sissle Orchestra toured bases all over the country as one of the USO “Camp Shows.” (Charlie Parker actually passed through one of Sissle’s bands in 1943.) Sissle then moved his family to Los Angeles where they rented one of the houses that had been vacated by its Japanese owners, who’d been moved to an internment camp. The USO then sent him over to Europe to entertain the troops with a small version of Shuffle Along. He performed it 157 times before servicemen in Italy, France, and Germany—an audience estimated at more than 1.25 Million.

Sissle stayed in Europe for a couple of years and when he returned, he wanted to move the family back to New York, but his absence had strained his marriage. Ethel Sissle had become involved in various projects, and she didn’t want to move the family. A divorce was initiated which apparently spun out over many years. The family stayed in L.A. while he moved to New York and lived with a nephew (who as I mentioned was not that much older than Sissle). A few years later, Ethel Sissle would be invited to become involved in a dress shop and move the family back to New York.

In 1946, Sissle danced and conducted his orchestra in a Soundies short called “Sizzle With Sissle.”

And, in 1947, he and his band appear in the film “Junction 88.”

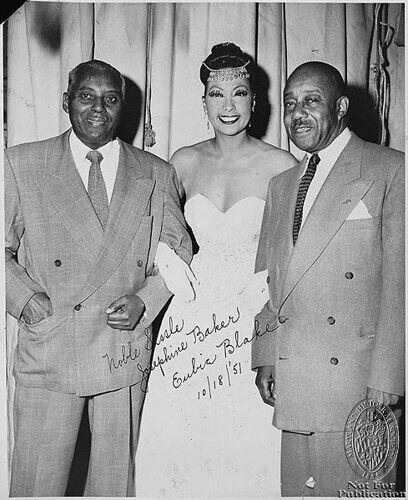

In the presidential election of 1948, Harry Truman used “I’m Just Wild About Harry” as a campaign song and rejuvenated interest in Shuffle Along. Sissle and Blake begin to come back as a nostalgia act, doing tunes from Shuffle Along with Blake also playing solo pieces. Efforts were made to produce a new, altered version of Shuffle in 1952, but the omens weren’t good. Sissle fell into the orchestra pit during a rehearsal and Pearl Bailey left the show before the opening. Efforts to denature and update the show seemingly doomed it to failure. [In 2016, the show was resurrected—with many changes—and played 138 performances on Broadway.]

Throughout the 1940s, Sissle wrote columns for the New York Age and Amsterdam News.

He succeeded Bill “Bojangles” Robinson as honorary mayor of Harlem in 1950 and when he accepted the post he pledged to work for “improving interfaith business, civil, and welfare relations in Greater New York.” He played at Eisenhower’s inauguration in 1953 and, in 1954, New York radio station WMGM signed Sissle as a disc jockey. Between 1950-1971, he appeared sporadically on television, either as a walk on, in the audience taking a bow, or acting.

He was a man of habits, Noble, Jr. says. Every day he would take the train downtown to go to ASCAP or wherever. For 20 years, he’d drive to Brooklyn and pick up Blake for gigs. Noble, Jr. told me a story that his aunt told him about the end of his dad’s life, involving one of his habits and the onset of dementia. “He still thinks it’s the ’40s, cause he always goes down two blocks at 11:00 at night to buy tomorrow’s newspaper. It’s a religious thing he’d do. And he went down night before last and we’re asleep and suddenly there’s a knock on the door. And a guy says ‘does Noble Sissle live here?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Well, I have something for him.’ ‘What?’ “Well, he was mugged on the corner down there by the newsstand and we were able to shoo the kids away and we have his wallet.” So I go back and he’s sitting there in his bedroom reading the newspaper. And the man says ‘Sir, we have your wallet.’ ‘Fine, where’d you get it?’ ‘Sir, you were just mugged down there at the corner.’ My dad says ‘I Was?’ ‘Yea, don’t you remember?’ ‘No, I don’t believe I do.’”

This was the signal, in 1972, that told Noble, Jr. he needed to be with his father. He went to New York and brought him back to his home in Tampa, Florida. He says that it was like “like Sanford and Son” and that the two years he spent with his father were “the best two and a half years of my life.”

Sissle and Blake had continued to perform and to write until 1968. Their last song was “Didn’t the Angels Sing for Martin Luther King” and Sissle’s last recording was 86 Years of Eubie Blake. Sissle died December 17, 1975. There was a well-attended service at St. Mark’s United Methodist Church and was he was buried in National Cemetery in Long Island.

There was an unusual constellation of values present in Noble Sissle that helps explain his long-term success. There was his musical skill as a singer, including his ability to deliver songs that might be labeled as vaudeville, ragtime, jazz, or popular. Working with Eubie Blake put him ahead of the game in terms of understanding the new, shifting notion of swing and his exposure to James Europe helped him understand what leadership meant. He had a levelheaded business sense, and a convivial personality that made him an indispensable collaborator with Europe and Eubie Blake. He was able to mix easily with people of all backgrounds, from the Prince of Wales to the non-English-speaking Puerto Ricans in the “Harlem Hellfighters’ Band.”

Then, there was his desire to improve the conditions of his race, which manifested throughout his life in service to his community and to the government. One cannot read what Sissle wrote about his time in the army and as Mayor of Harlem and not feel the decency of the man. One reads with a certain ruefulness Sissle’s optimistic belief that serving his country will result in greater opportunities for his people, but his sincerity is undeniable and he led a life consistent with that sincerity.

I’d like to thank Noble Sissle, Jr. for his generous contribution to this story. Noble, Jr. helped to organize a band of 42 musicians from Historically Black Colleges and Universities that has travelled the country playing the sounds of the 369th Infantry Harlem Hellfighters Regimental Band. There is a documentary about Noble Sissle, Jr. on Youtube.

Apart from conversations with Noble, Jr., I also used the book Reminiscing with Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake by Robert Kimball and William Bolcom, a manuscript of an unpublished biography of James Europe by Noble Sissle, and a number of websites as resources for this story.

Steve Provizer is a brass player, arranger and writer. He has written about jazz for a number of print and online publications and has blogged for a number of years at: brilliantcornersabostonjazzblog.blogspot.com. He is also a proud member of the Screen Actors Guild.