In recent years, the song “Lift Every Voice and Sing” has reentered the public consciousness. Depending on who is telling the story, the work is either a Christian hymn, a celebration of the African American experience, or a separate national anthem for a separate people. Amidst the debates and ballyhoo over the song’s sometimes inclusion at sports events alongside the Star-Spangled Banner, very little is ever said of the piece’s lyricist, James Weldon Johnson.

This man led an eventful life to the highest degree, he not only wrote over 200 other popular songs but also advised two American presidents, served as the official US Consul in Nicaragua and Venezuela, filled various leadership capacities at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and was part of the failed but nonetheless fruitful effort to make lynching a federal crime. James Weldon Johnson offered through both his observances and compositions a window to the burgeoning American music industry, the struggles and joys of African American lives, and geo-political changes that occurred in the first half of the 20th Century.

Born and raised in Jacksonville, Florida, to a waiter father and homemaker mother, Johnson’s first exposure to music was through the church. Though through most of James Weldon’s life he would retain a kind of agnosticism on the existence and nature of God, the church would have a profound effect on his thinking and eventually his own production of art. But early on, some of the forms of religious expression—especially in the colored St. Paul’s Church—could put fear in the young boy.

This was especially present in James Weldon’s Aunt Venie, the local “champion” of a form of worship called “ring shout.” Johnson would recall in his autobiography, “When there was a ring shout, the weird music and the sound of thudding feet set the silences of the night vibrating and throbbing with a vague terror. Many a time I woke suddenly and lay a long while strangely troubled by these sounds…The shouters, formed in a ring, men and women alternating, their bodies close together, moved round and round on shuffling feet that never left the floor. With the heel of the right foot they pounded out the fundamental beat of the dance and with their hands clapped out the varying rhythmical accents of the chant; for the music was, in fact, an African chant and the shout an African dance, the whole pagan rite transplanted and adapted to Christian worship. Round and round the ring would go: one, two, three, four, five hours, the very monotony of sound and motion inducing an ecstatic frenzy. Aunt Venie, it seems, never, even after the hardest day of washing and ironing, missed a ring shout.”

At a young age, Johnson and his brother John Rosamond began one of many “friendly rivalries”: music. Rosamond was the better pianist of the two, though James Weldon surpassed his brother on the guitar and violin. It was James Weldon’s discovery of a book called Music and Some Highly Musical People that seemed to set a course for his life. The book told brief stories of such Negro musicians as Blind Tom and The Black Swan, in addition to including popular and important compositions.

Among the songs included a march titled “Welcome to the Era” which Johnson learned and perfected on the piano. The first time Rosamond heard the tune, “He at once wanted to know where I had got it; and I would not tell him. He searched through all the sheets of music and music books we had; naturally, not thinking to look in a book that appeared to be filled only with reading matter. I got keen joy out of the satisfaction that I had, at least, one piece that he couldn’t beat me playing. However, my satisfaction lasted only until Rosamond let go the repertory of six or eight new pieces he had learned in New York [their parents hometown], his star piece being ‘See-Saw,’ a waltz song and the overwhelmingly popular hit of the year Eighteen Hundred and Eighty-Five. I may say that ‘See-Saw’ snuffed out any future as a pianist that I might have had.”

Next James Weldon became obsessed with becoming a drummer, he inspired by the many black dominated brass bands that proliferated in Florida in the late 1800s. Johnson reports that all of the militias—be they black or white—always marched behind a black band because they were considered to be the best. Jacksonville had their own band called the Union Cornet Band, which featured a “crack” drummer by the name of Martin Dixon. “A slim, good-looking black dandy,” as Johnson described him, Dixon had been a drummer boy during the Civil War. “The boys in Jacksonville, black and white, boasted that when the band played for a funeral, Martin could beat a continuous and unbroken roll on his muffled drum all the way from the church to the cemetery. I did not see how life could offer anything happier than marching behind the blaring brass beating a drum as Martin Dixon did and enjoying the admiration and envy of all the boys in town. I lost my ambition to be a drummer, but drums have never lost their tumultuous effect on me.”

Jacksonville would have its share of national guests to visit the town, a few of which would inspire the young James Weldon. The first was former Union General and the then Republican President Ulysses S. Grant, who had by way of creating the federal Justice Department worked to crush the terroristic Ku Klux Klan by prosecuting over 600 of its members for violence and property damage, much of it against the newly freed black population. Grant’s visit to the town must’ve been a curious event, given white population of Jacksonville’s allegiance to the former Confederacy and the Democratic Party. Still, Johnson reports that people of all hues came out to get a look at the president.

James Weldon and his family proudly joined a line of people who would get to pass very close by the president. In a moment of unexpected courage when the Johnson family got near enough, James put out his hand to the old general, at which Mr. Grant received it with his. The young Johnson was thrilled, although his action was overshadowed by a local colored woman feared for her sometimes “violent” language, who ended up throwing her arms around the president, kissing him on the cheek and then presenting him with flowers. The black population of Jacksonville was quite embarrassed by the strange actions of the woman but the president didn’t make an issue of the occurrence.

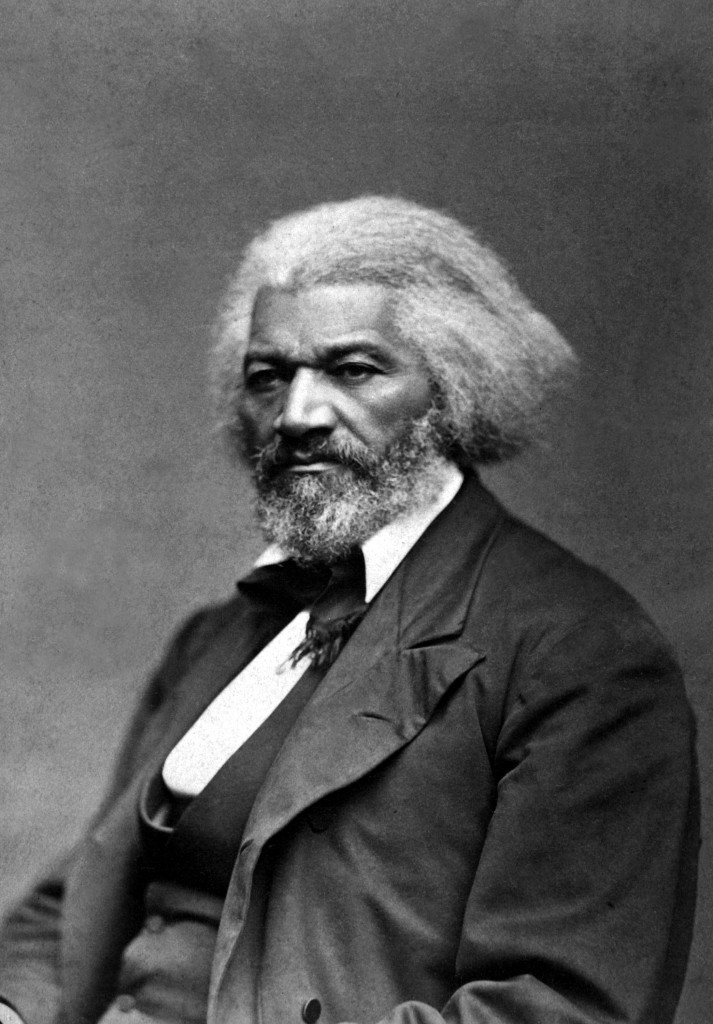

The next visitor to Jacksonville to make a great impression on the young James Weldon Johnson was the great Frederick Douglass. Famously known as the man who had been born into slavery yet escaped his bondage only to become one of the most powerful forces against “property in man,” Douglass would go on to advise President Lincoln and occupy several prominent posts in the United States government, including consul-general to Haiti. At seeing the statesman with his mane-like white hair, Johnson later wrote, “I was filled with a feeling of worshipful awe. Douglass spoke and moved a large audience of white and colored people by his supreme eloquence.”

Academically Johnson would excel in his performances, going on to attend Atlanta University, a school established by former slaves for blacks after the end of the Civil War. There Johnson would come to admire the mostly white teaching staff, given their loss of social status among the greater Atlanta population. The white teachers were deemed “unclean” for not only their efforts in educating black students but for allowing their own children to attend the school as well.

In addition, it was at Atlanta University that James Weldon Johnson would begin singing bass in a college-formed group called Atlanta University Quartette. Much like the legendary Fisk Jubilee Singers of Fisk University, this group would tour various parts of the United States to not only attempt to attract future students but raise money for the institution as well.

One song that would serve to be popular for the group’s performances was called, “He Never Came Back.” According to Johnson, “The first verse told the story of a soldier kissing his wife good-by, going to the war, leaving ‘the one he did adore.’ The chorus went on to relate that he never came back-and ‘how happy she’ll be, his sweet face to see, when they meet on that beautiful shore.’ The second verse told the story of a man going into a restaurant, calling the waiter, and ordering a steak: of how the man waited and waited for the waiter; but in the chorus—he never came back, and ‘his face I will break, if I don’t get that steak, when we meet on that beautiful shore.’”

There were additional verses that played off the same thematic gimmick. Johnson went on to tell a story about the quartet visiting a town where they were to hold a concert and one of the members went to a white barbershop to have himself shaved. Times what they were, the black musician was refused service. But the Atlanta University Quartette got the last word by turning “He Never Came Back” in a protest song at their evening performance, they adding an additional verse.

“A certain little barber

In a certain little town

Refused to shave another man

Because his face was brown.

That barber’s face

Although it’s white

His heart is very black;

And when he goes to regions warm

He’ll never come back,

His face here we’ll see never more;

O, but how he will crave for a brown face to shave,

When we meet on that beautiful shore.”

James Weldon Johnson finished his education and moved back to Jacksonville to become a principal of a school, became the first black man in Florida to take the bar exam, practiced law and for a brief time created and edited a newspaper. During this time his brother Rosamond went to Boston to study music. In 1896, Rosamond was tapped by John W. Isham for a musical production called Oriental America. Energized by the experience, Rosamond began composing music for lyrics that James Weldon had written in some notebooks.

The two in time composed an operetta that was performed at the school that James Weldon managed, which was enthusiastically received by audiences of both races in Jacksonville and inspired the brothers to make a major gamble with their lives. The two left for New York where they immediately met with an editor of a music trade journal. The editor’s chief advice to the brothers was to copyright everything they wrote as that, “New York was full of pirates just waiting for the chance to plunder.”

The first project they worked on was a light opera called Tolosa. The first professionals they purposed to play it for were the most popular composers Harry B. Smith and Reginald DeKoven, known for their popular operetta adaptation of Robin Hood. Ready to size up these young men from Florida, Smith commented, “Let’s hear it; we might be able to steal something from it.” Remembering the first advice they received when entering the big city, the brothers Johnson promptly took their work elsewhere. While Tolosa was never produced formerly, the work did attract the attention of one Oscar Hammerstein who came to hear the material without managing to steal it.

In time Rosamond and James Weldon were introduced several of the artistic stars of the age. One was singer and composer Harry T. Burleigh who was popular among both black and white audiences and would be credited for teaching Negro Spirituals to Czech composer Antonin Dvorak. There was also the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar who which James Weldon deeply admired and would try to imitate, especially when it came to writing verse in the Negro dialect.

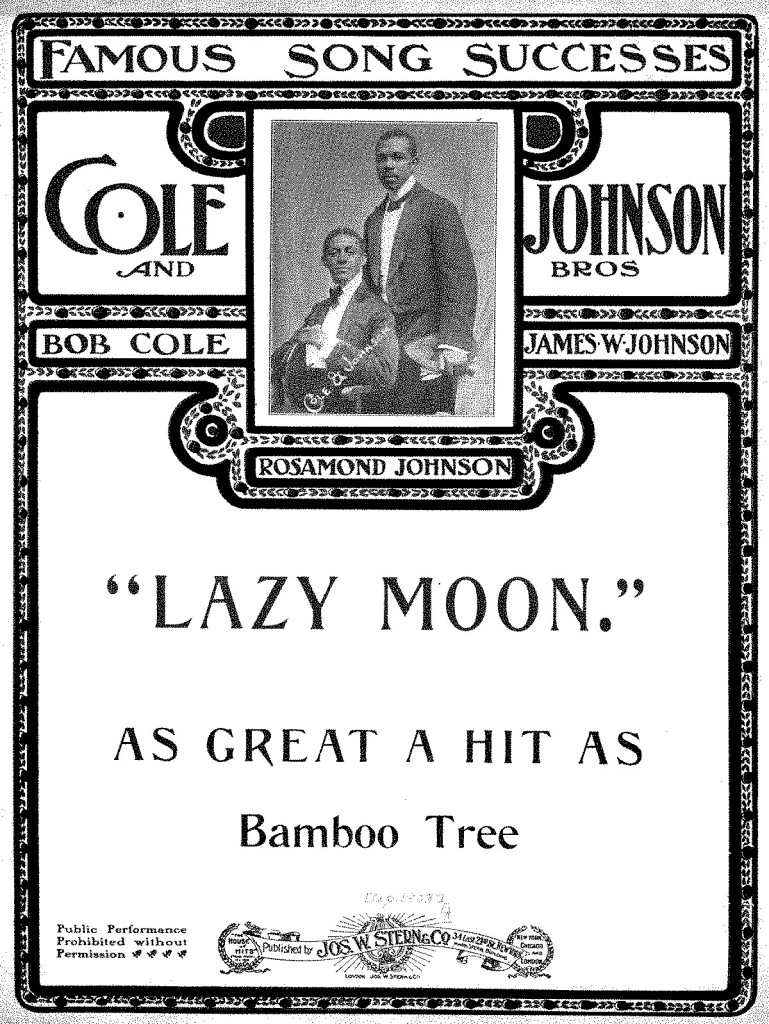

But the individual that would serve to take the Johnson brothers to great heights was Bob Cole, a multitalented performer and composer having been part of Black Patti’s Troubadours and went on to create the first all-black produced musical, A Trip to Coontown. As a trio, one of the first projects the men tackled was in trying to make “Negro songs” more respectable. According to James Weldon Johnson, “The Negro songs [that were all] the rage were known as ‘coon songs’ and were concerned with jamborees of various sorts and the play of razors, with gastronomical delights of chicken, pork chops and watermelon, and with the experiences of red-hot ‘mammas’ and their never too faithful ‘papas.’ These songs were for the most part crude, raucous, bawdy, often obscene.”

Their first product was “Louisiana Lize,” which the three sold to the performance rights to Vaudeville “coon shouter” and subject of the short Thomas Edison Kinetoscope film The Kiss, May Irwin, for fifty dollars. The Johnsons and Cole then made a deal with Jos. W. Stern and Co to publish the work.

The Johnson Brothers frequented the many clubs in New York City where talent from various “professions” could be witnessed. The venues served as “meeting places” for blacks with particular interests, the most popular being spaces for those in the world of professional boxing or the theatrical arts. Some clubs allowed gambling, others forbade it. Many whites frequented these venues as well, usually interested in finding out what was the latest in “Negro stuff.” And according to James Weldon, there were always a healthy amount of white women who were on the prowl for new “colored lovers.”

James Weldon returned to Jacksonville where in the year 1900 there was being organized a celebration of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. Asked to be one of the speakers, Johnson also decided to compose a poem for the event. As the verses began to take shape, James decided to have Rosamond write music for the words, which school children could sing at the celebration. When Johnson finally completed the work, he later wrote, “I could not keep back the tears, and made no effort to do so. I was experiencing the transports of the poet’s ecstasy. Feverish ecstasy was followed by that contentment that sense of serene joy which makes artistic creation the most complete of all human experiences.”

The words from the man who was still unsure about God were these:

“Lift every voice and sing,

’Til earth and heaven ring,

Ring with the harmonies of Liberty…

Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us…

God of our weary years,

God of our silent tears,

Thou who hast brought us thus far on our way,

Thou who hast by Thy might

Let us into the light,

Keep us forever in the path, we pray;

Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee,

Lest, our hearts drunk with the wine of the world, we forget Thee.”

The song was a hit at the Lincoln celebration and continued to be sung by children of both colors within and outside of Jacksonville and began to appear in hymnals. Over the next twenty years, the popularity of the work grew until it was adopted in 1917 by the National Association of the Advancement of Colored Peoples as the anthem of black Americans. James Weldon Johnson would later observe, “My brother and I, in talking, have often marveled at the results that have followed what we considered an incidental effort, and effort made under stress and with no intention other than to meet the needs of a particular moment. The only comment we can make is that we wrote better than we knew.”

Back in New York City also around 1900, a new hot spot for black talent emerged in the Tenderloin district: The Marshall Hotel. Situated on 52nd Street and black-owned, soon most of the preeminent colored talent of the time period were abandoning their previously lauded clubs for the classier Marshall. One such figure was Bert Williams, who was a West Indian minstrel comedian and singer who helped popularize the cakewalk dance and would go on to be the most popular black recording artist until his death in the early 1920s. James Weldon Johnson described the man at that time as, “Tall and broad-shouldered; on the whole, a rather handsome figure, and entirely unrecognizable as the shambling, shuffling ‘darky’ he impersonated on the stage; luxury-loving and indolent, but highly intelligent and with a certain reserve which at times exhibited itself as downright snobbishness; talking with a very slow drawl and getting more satisfaction it seemed, out of being considered a great raconteur than out of being a great comedian.”

Other celebrities of the age such as Ernest Hogan, George Walker, and his wife Aida Overton helped The Marshall Hotel to continue to dominate as the most prestigious black gathering over the next decade, so much so that its popularity ended up on the radar of a progressive social activist group. Even after the police investigated the establishment and found that the Marshall seemed to follow closely all of the local laws and ordinances, a temperance group called the Committee of Fourteen sent in spies, which discovered “race mixing.” After some pressure from the New York police, the hotel’s owner James Marshall agreed to keep the white and black patrons from getting too close while visiting.

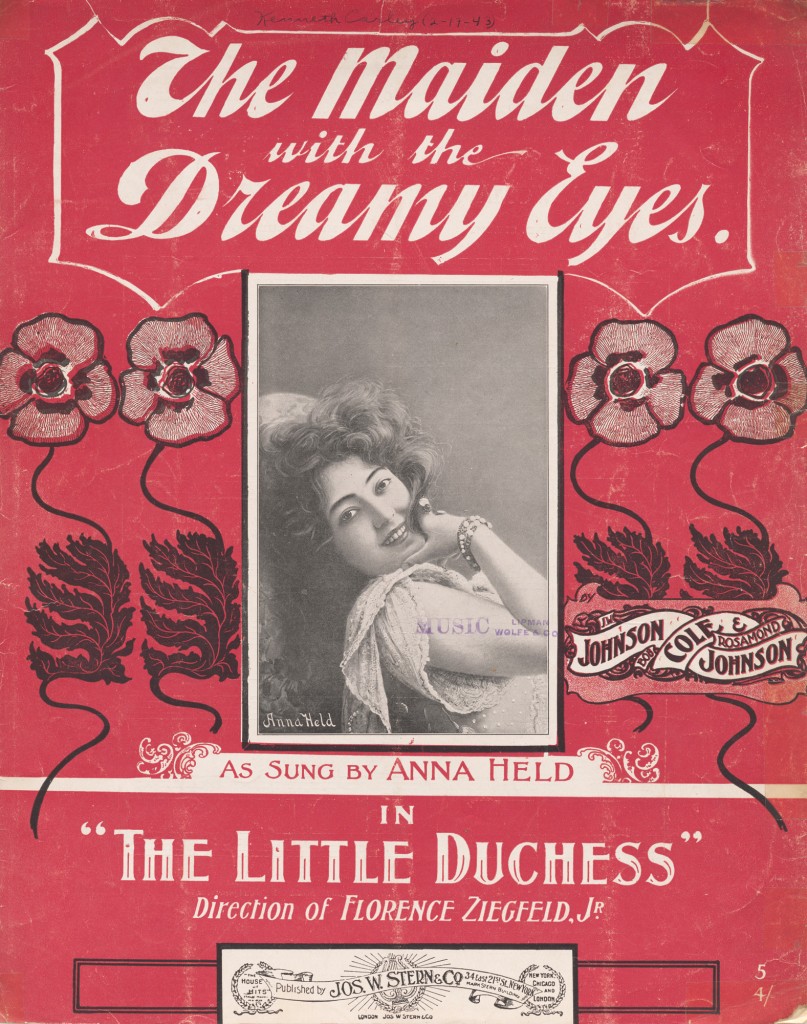

The Johnson brothers along with Bob Cole continued to turn out a steady stream of popular songs including, “Run, Brudder Possum, Run,” “Nobody’s Lookin’ but the Owl and the Moon,” “Under the Bamboo Tree,” “Congo Love Song,” “Sally in our Alley,” “The Old Flag Never Touched the Ground,” “My Castle on the Nile,” and “The Maiden with the Dreamy Eyes.” When reflecting on what kind of formulas would cause a song to garner the most royalties, James Weldon Johnson explained using “The Maiden with the Dreamy Eyes” as a case in point, “A writer depended largely upon the young fellow who would buy a copy of the song and take it along with him when he went to call on his girl, so that she would play it while the two of them gave vocal vent to the sentiments…In writing ‘The Maiden with the Dreamy Eyes’ we gave particular consideration to these fundamentals.

“It needed little analysis to see that a song written in exclusive praise of blue eyes was cut off at once from about three-fourths of the possible chances for universal success: that it could make but faint appeal to the heart or pocketbook of a young man going to call on a girl with brown eyes or black eyes or gray eyes.

“So, we worked on the chorus of our song until, without making it a catalogue, it was inclusive enough to enable any girl who sang it or to whom it was sung to fancy herself the maiden with the dreamy eyes. It ran: ‘There are eyes of blue, there are brown eyes too/There are eyes of every size and eyes of every hue/ But I surmise that if you are wise/You’ll be careful of the maiden with the dreamy eyes.’”

One interpreter of “The Maiden with the Dreamy Eyes” was Anna Held, who was married to one Florenz Ziegfeld. In time the aspiring producer would invite James and Rosamond to his summer vacation spot so that they could pitch additional songs for Held. James Weldon was struck by how low key and “semi-invalid” Ziegfeld was, especially when compared with the usual “dictatorial, obstreperous” producers of the age. Yet there was at least one instance when James Weldon witnessed Ziegfeld come to life with a display of fiery emotion.

The Johnson brothers were to meet the producer at his apartment in the Ansonia Hotel and when they entered the building, the black men were told that they could go up but they would have to use the service elevator. When they called Ziegfeld to inform him of the slight, the producer himself came downstairs and argued with the hotel staff, who claimed they were just following the rules. Ziegfeld ignored the excuses of the workers and ordered the Johnson brothers to ride up with him on the guest elevator. James Weldon would witness other egalitarian actions on the part of Ziegfeld, notably when the producer made the colored performer Bert Williams the star of The Follies, this in spite of some of the white performers threatening to quit.

Because of Johnson brothers’ increasing output of popular material, the two were able to pay down all of their debts and could finally live the good life. Yet James Weldon had seen what the price of success had cost others, he noting that it was “a heady beverage. It can be as deleterious as any alcoholic drink. It seems to me that a man drunk with success is more of a fool than the maudlin inebriate; and, certainly, he is more dangerous to himself and to others. Success is safe only when it comes slowly, and even then is not entirely so. We had been struggling for four years; yet, when success did come, it seemed sudden. It magically blotted out the memory of all our disappointments and defeats and carried us up into a region above doubts and fears, to that height where success of itself begets success.” Thus, Rosamond and James Weldon consciously tried to keep cool heads during the sudden interest that everyone from actors to royalty were paying the brothers, in spite of the conventional wisdom that, “In the artistic world, anything, from wearing strange-looking clothes to committing manslaughter, may be justified under the head of ‘publicity.’”

One unique aspect of the brothers’ success is that outside of the New York City musical world, many were not aware of the race of the new superstar composers. James Weldon relayed one instance where Edward Bok, the white editor of The Ladies Home Journal, handed the composer a letter he had received after the magazine had published a song by an unknown black composer in Georgia. The composition prompted a curt letter from a white Georgian woman who declared that colored people did not have the capability of producing quality versions of even their own art forms, whites being the better interpreters of black music. She advised that in the future, The Ladies Home Journal “give us some more of those little Negro classics by Cole and Johnson Brothers.”

One unique aspect of the brothers’ success is that outside of the New York City musical world, many were not aware of the race of the new superstar composers. James Weldon relayed one instance where Edward Bok, the white editor of The Ladies Home Journal, handed the composer a letter he had received after the magazine had published a song by an unknown black composer in Georgia. The composition prompted a curt letter from a white Georgian woman who declared that colored people did not have the capability of producing quality versions of even their own art forms, whites being the better interpreters of black music. She advised that in the future, The Ladies Home Journal “give us some more of those little Negro classics by Cole and Johnson Brothers.”

Also during this time period, James Weldon Johnson was involved in several stage productions that often featuring his compositions. One idea James Weldon always regretted never following through on was adapting Joel Chandler Harris’ Uncle Remus stories for the musical stage. Harris had been a Georgia journalist and had sought to preserve Southern negro folklore that he felt was being forgotten with the passing of each generation. The journalist even disciplined himself to only publish tales that he could verify from two different sources.

The book would be a hit and jumpstart an interest in American folklore in general. While James Weldon never did follow through on the idea for the musical production of the book, someone else would. In 1946—8 years after Johnson’s death—Walt Disney would release Song of the South, a musical film that employed both live actors and animation to put Uncle Remus and his stories on the screen, many of its songs—including “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah”—still in the American national consciousness.

In 1904, a black Republican Party activist and friend of James Weldon approached the composer about helping establish a “Colored Republican Club.” In spite of his lack of political experience, James Weldon agreed and soon was rubbing elbows with many of the black Republican elite, they all coming together for the upcoming election to help keep Theodore Roosevelt in the White House. Cole and the Johnson Brothers even composed a campaign song titled, “Teddy” or “You’re all right, Teddy.” One of the verses sang:

“When Europe raised a fuss

And tried to say to us:

‘What? Dig through Panama, you never shall!’

Our Teddy said: ‘All right!

I’ll think if over for a night.’

Next day we got the Panama Canal.”

The man himself after having heard the song, sent a note to the composers, praising it as “a bully good song.” In time “TR” would return the support by appointing James Weldon as the consulate in Venezuela. Thanks to having had a Cuban friend during his youth in Florida, James Weldon spoke fluent Spanish, thus making him at least partially prepared for the task.

Though his time over the next few years in South America would take James Weldon away from his composing any more popular songs, his life would become more meaningful and vital to both the government of the United States and the people in the Latin American nations he would find himself in. Quickly learning of the volatility of South American politics, James Weldon witnessed one president of Venezuela who went to Germany to have a life-saving surgery and in his attempt to return home found that his nation had not only had undergone a revolutionary uprising, but that the revolt had been crushed by the Vice-President, who now assumed the presidency and would not allow the former president back in the country.

Later, James Weldon was sent to perform the same diplomatic role in Nicaragua, where one morning he found a “terror-haunted” man banging on the front door of the consulate in Corinto, only to discover that it was the current president of that country seeking political asylum. Sometime after this, another uprising in Nicaragua was commenced, the rebels conducting a slaughter in the nearby city of Leon and seemed to be planning the same for Corinto, but James Weldon was able to negotiate a temporary cease fire, buying time until American Marines could arrive and restore the peace. God only knows how many Nicaraguan citizens James Weldon Johnson had saved from being massacred.

In 1910, James Weldon married Grace Nail, a woman so fair-skinned she was often confused as one hundred percent Caucasian. She joined him in Nicaragua and began learning Spanish to assist her husband in his diplomatic duties.

While still in Nicaragua, James Weldon would receive some terrible news in 1911: Bob Cole had drowned in the Catskills. Cole’s fortunes had declined in the preceding years, it culminating in a mental breakdown at Keith’s Fifth Avenue Theatre. James Weldon would later write that in addition to his grief of loss for Cole, he also felt “deep contentment” that they had been friends and created so much wonderful material together.

James Weldon continued to serve in his diplomatic role through the Taft presidency. But in 1912 the Republican Taft faced off against Teddy Roosevelt (who had left the Republican Party to form his own Progressive/Bull-Moose Party) and Democrat Woodrow Wilson. Wilson prevailed and immediately both instituted Jim Crow segregation into the federal government (even barring blacks from entering post offices, they having to use outside windows) and fired hundreds of the blacks from their posts. Beating the president to the punch, James Weldon resigned and moved back to America before he could be fired.

Amid all of his geopolitical adventures, James Weldon had not only refined his poetry writing skills that would result in the collection God’s Trombones but would begin work on and completed a piece of fiction entitled The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man. Not sure of the quality of his narrative style, Johnson published the book anonymously. James Weldon based the story off of many figures that he had known in his life, including himself. The narrator is a black man that is so light skinned that he often passes for white. He also becomes a master of ragtime piano playing. In one story while playing in a club, a white “slummer” becomes intrigued with the pianist’s skills and hires him to play a dinner party at his apartment. The narrator relays the events of the proceeding evening:

Amid all of his geopolitical adventures, James Weldon had not only refined his poetry writing skills that would result in the collection God’s Trombones but would begin work on and completed a piece of fiction entitled The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man. Not sure of the quality of his narrative style, Johnson published the book anonymously. James Weldon based the story off of many figures that he had known in his life, including himself. The narrator is a black man that is so light skinned that he often passes for white. He also becomes a master of ragtime piano playing. In one story while playing in a club, a white “slummer” becomes intrigued with the pianist’s skills and hires him to play a dinner party at his apartment. The narrator relays the events of the proceeding evening:

“When dinner was served, the piano was moved and the door left open, so that the company might hear the music while eating. At a word from the host I struck up one of my liveliest ragtime pieces. The effect was surprising, perhaps even to the host; the ragtime music came very near spoiling the party so far as eating the dinner was concerned.

“As soon as I began, the conversation suddenly stopped. It was a pleasure to me to watch the expression of astonishment and delight that grew on the faces of everybody. These were people—and they represented a large class—who were ever expecting to find happiness in novelty, each day restlessly exploring and exhausting every resource of this great city that might possibly furnish a new sensation or awaken a fresh emotion, and who were always grateful to anyone who aided them in their quest.

“Several of the women left the table and gathered about the piano. They watched my fingers and asked what kind of music it was that I was playing, where I had learned it, and a host of other questions. It was only by being repeatedly called back to the table that they were induced to finish their dinner. When the guests arose, I struck up my ragtime transcription of Mendelssohn’s ‘Wedding March,’ playing it with terrific chromatic octave runs in the bass. This raised everybody’s spirits to the highest point of gaiety, and the whole company involuntarily and unconsciously did an impromptu cake-walk. From that time on until the time of leaving they kept me so busy that my arms ached.”

James Weldon included many similar musical happenstances throughout the narrative that helped admirers of early American popular music feel as if they were not just a few feet from the protagonist’s piano.

Sometime after returning to the States, James Weldon would become editor of the Black publication The New York Age, contributing many articles himself, many of them aimed at the unabashed racism of the Wilson administration. He also began writing songs again, this time of the “higher” form, in which he collaborated with Harry T. Burleigh, Will Marion Cook, and of course his brother Rosamond. “Sence you went away” made popular by John McCormack came from this time period.

“Seems lak to me…

De stars doan shine so bright

De sun done los’ his light

De day’s jes twice as long

De bird’s forgot his song

Sence you went away.”

One figure from the opera world that James Weldon would work with briefly was the Spanish composer Enrique Granados. One evening, Granados, his wife, and Johnson would go to dinner where it was revealed that the opera composer had around ten thousand dollars’ worth of gold and banknotes strapped and hidden inside a belt at his waist. Granados was eager to get back to Spain with his earnings and so he and his wife set sail. This being the mid-1910s, the ship they were aboard, the Lusitania, was torpedoed by a German submarine. James Weldon would later mournfully observe, “The treasure that he was carrying home helped to carry him down.”

In 1916, Johnson would be invited to work for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. There he often interacted with W.E.B. Du Bois and other leaders in the post-Booker T. Washington civil rights movement. In addition to Wilson’s hostilities against Blacks, James Weldon also put much focus on the often-unpunished nation-wide (though more prominently in the South) practice of lynching.

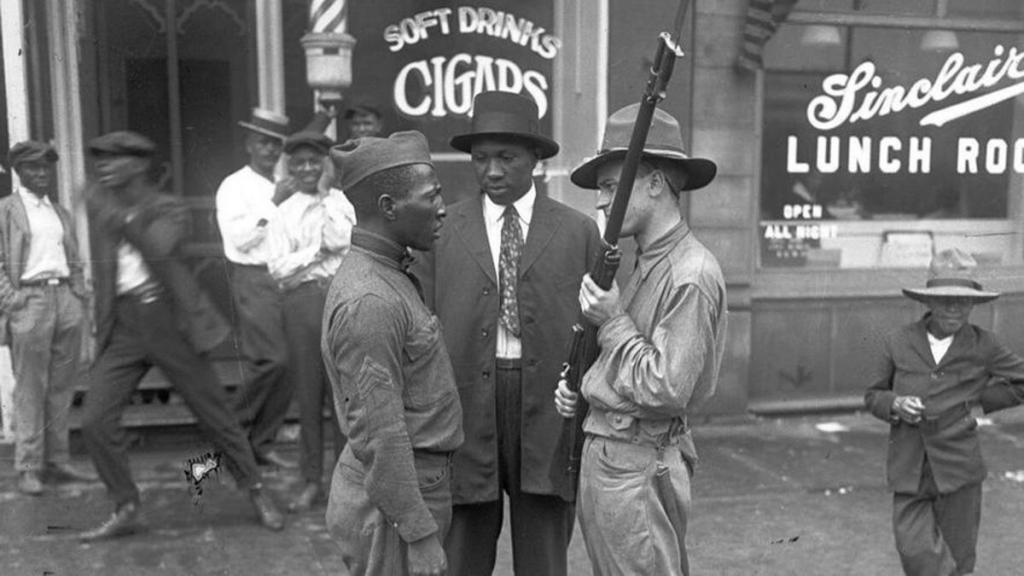

The fight to make this violation of constitutional due process a federal crime was one that had been championed for years by Memphis journalist Ida Wells and Missouri Republican congressman Leonidas Dyer but was always defeated by Democrats in Congress. Indeed, President Wilson himself was on record for praising the Reconstruction-era Ku Klux Klan and screened the film Birth of a Nation—which portrayed the terrorist group into heroes—at the White House. The year 1919 was an especially violent year, as that riots that often involved soldiers of both races returning from the Great War broke out in many American cities, most notably in Washington, DC, and Chicago. One tactic used at the time to assist the white supremacy of the day was for Democratic city prosecutors to never charge the white aggressors for their crimes, which invited a kind of open season on blacks.

James Weldon and other used their platforms to relay grisly tales of the 3436 blacks and whites (there had been on average one white for every three blacks lynched) being shot, hung, and burned alive from 1889 to 1921. Finally, a great ally to the cause against lynching came in the person of Warren Harding. An Ohio Republican who for years Democrats had accused of having “Negro blood,” Harding became president in 1921, he soon gave a speech to a segregated crowd in Alabama where he not only lectured on the evils of segregation but vowed to sign any anti-lynching law if it was put upon his desk.

In 1922, while the Republican House of Representatives—with at least one Democratic voice of support—passed the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, Democrats in the Senate filibustered, and according to Johnson some Republicans in the Senate gave up on trying to overcome the filibuster and the effort again was defeated. Yet surprisingly, there was a silver tinge. In the years following the failure of the law, lynching dropped dramatically. James Weldon would muse that the national attention called the practice in the places where it happened had “served to awaken the people of the Southern states to the necessity of taking steps themselves to wipe out the crime.” Again, one wonders how many lives Johnson’s hard work had saved.

While James Weldon continued to involve himself with national politics, music never left his mind. The Johnson brothers published The Book of American Negro Spirituals in 1925, becoming a popular reference guide for the musical art form. In the late 1920s, recordings by various groups of a song written by James Weldon and Rosamond began to appear that had been inspired by the Biblical prophet Ezekiel’s vision of skeletons coming back to life, eventually coming to be known as “Dem Bones.”

While James Weldon continued to involve himself with national politics, music never left his mind. The Johnson brothers published The Book of American Negro Spirituals in 1925, becoming a popular reference guide for the musical art form. In the late 1920s, recordings by various groups of a song written by James Weldon and Rosamond began to appear that had been inspired by the Biblical prophet Ezekiel’s vision of skeletons coming back to life, eventually coming to be known as “Dem Bones.”

James Weldon wrote a history of musical New York called Black Manhattan, which was published in 1930. Finally in 1934, he released his actual autobiography, Along This Way. Then four years later James Weldon Johnson died when a train struck the car that he and wife Grace Nail were in. A large attended funeral was conducted in Harlem. He was 67.

It is perhaps fitting to end with James Weldon Johnson’s observation about the nature of American popular music, of which he has such a prominent hand.

“The Negro has given America its best-known distinctive form of art…This lighter music has been fused and then developed, chiefly by Jewish musicians, until it has become our national medium for expressing ourselves musically in popular form, and it bids fair to become a basic element in the future great American music. The part it plays in American life and its acceptance by the world at large cannot be ignored. It is to this music that America in general gives itself over in its leisure hours, when it is not engaged in the struggles imposed upon it by the exigencies of present-day American life. At these times, the Negro drags his captors captive.

“On occasions, I have been amazed and amused watching white people dancing to a Negro band in a Harlem cabaret; attempting to throw off the crusts and layers of inhibitions laid on by sophisticated civilization; striving to yield to the feel and experience of abandon; seeking to recapture a taste of primitive joy in life and living; trying to work their way back into that jungle which was the original Garden of Eden; in a word, doing their best to pass for colored.”

Quotes taken from Along This Way by James Weldon Johnson.

Related Articles from The Syncopated Times, most of these articles are outside our paywall to make them easily accessible for educational use.

The Product of Our Souls: Ragtime, Race, and the Birth of the Manhattan Musical Marketplace

Noble Sissle: A Messenger of Musical Uplift

James Reese Europe: ‘The MLK of American Music’

In 1920 Mamie Smith’s Crazy Blues paved the way for Black Music

1920: The Year Broadway Learned To Syncopate

Ragged but Right: Black Traveling Shows, ‘Coon Songs,’ and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz

James Reese Europe and the Clef Club Orchestra at Carnegie Hall

Eubie Blake: Rags, Rhythm and Race

Spun Counterguy is an American history professor and author of the booksThe Ten Tracks Mixtape TasksandNest of ‘em.