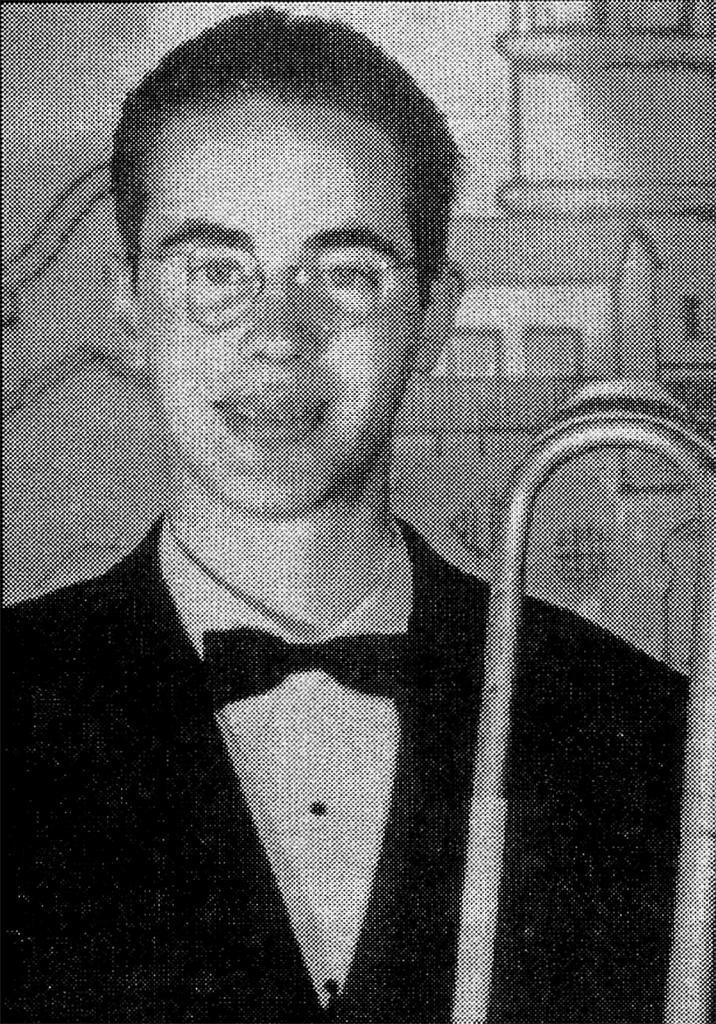

Whether you love New Orleans tailgate trombone or sophisticated Swing, Bill Bardin (1924 – 2011) is your man for tasteful, expressive jazz trombone. He was second to none in the San Francisco Jazz Traditional Jazz Revival for playing two-beat stomps, four-beat Swing or the lowdown Blues. His eloquent instrumental voice brought rich tone, thoughtful soloing and a unifying spirit to any ensemble.

Bill was lucky and knew it. In the vivid interview quoted below, he modestly recounts his encounters with remarkable performers: Bunk Johnson, Earl Hines, Frank Goudie, Clancy Hayes, Bob Mielke, Bob Helm and Burt Bales. For six decades, he rode the first and second waves of the Frisco Jazz Revival.

One of his earliest steady jobs around 1948-49 was playing at what he calls a ‘dime jig.’ The Broadway Dancing Academy was a “taxi dance hall” operating in Oakland from 1919 to 1964.

Clip 1 Early Days Taxi Dances 1940s

Clip Joints and Dime Jigs:

“I played at the clip joints in the Tenderloin for a while . . . the Chez Paris and The Streets of Paris. Later I played at one of the ‘dime jigs’ in Oakland; that’s a taxi dance hall. It was twelve-and-a-half cents a dance then. Each tune lasted only a chorus or a chorus and a half. Each dance lasted one minute or maybe a minute-and-a-half.

It was a steady job for the leader . . . a drummer who had been there since 1935. There were five pieces hired but most of the night there were only four playing because it was continuous music. We had to take an intermission . . . so, we’d rotate. Sometimes I had to play drums and someone else would have to play piano. But you learned a lot of tunes.

And as I recall, at The Broadway there were the same mistakes at the same place every night, the same fluffs. I knew that on “Diane” I was gonna miss the high note. And I never let myself down.”

Clip 2 Earliest Jazz & performance

Inspirations

As a boy Bill was encouraged to take up music by his mother. He’d wanted to play jazz cornet like Louis Armstrong but got stuck with trombone and never changed.

“Oh, it just knocked me out!” said Bill about his earliest opportunity to sit-in at a fraternity dance with a “good band,” sometime before 1940. “The first time I played with a four-piece rhythm section and it was really great.” He became lifelong friends with the musicians, P.T. Stanton (cornet, occasionally guitar) and Pete Allen (alto sax or clarinet). “Later on [we] had jam sessions in Pete Allen’s mother’s living room in Berkeley.”

In 1939 Bardin first heard his lifelong inspiration, trombone player Dickie Wells (1907-1985) with the Count Basie Orchestra at the Golden Gate Exposition on Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay. Throughout his career, Bill sought to emulate Wells’ knack for focusing a band’s sound using “harmonic nudges here and there.”

Clip 3 Early Inspirations 1 Tricky Sam & Dickie Wells

Meeting Dickie Wells:

“It was like meeting Louis Armstrong for me. . . I first heard him with Basie . . . and again at Sweet’s Ballroom. I talked to him at Sweet’s a little bit. Or stood around and watched him put his trombone in his case.

I also saw him with Earl Hines and talked to him when Hines was at the [Club] Hangover. Dickie Wells was really at the height of his powers then. He was arranging for Hines and playing. What a band. That was before Hines went into the Hangover for his LONG Dixieland stay.

Much later, when he put his book out . . . I wrote to him care of Local 802 in New York and asked him something about a mouthpiece. And he wrote back a very cordial letter calling me ‘Ol’ Dude.’ And so, we exchanged Christmas cards for a while.”

Clip 4 Early Inspirations 2 Dickie Wells

Clip 5 Earliest musical memories

A Professional Musician at Age 17

Bill Bardin was not a child prodigy. But he became a professional musician at a tender age, holding his own with skilled professionals and living legends. He was often befriended and taken under the wing of more experienced musicians like reed player and bassist Pete Allen, pianist Burt Bales or clarinetist Ellis Horne (‘one of nature’s noblemen’) and his wife.

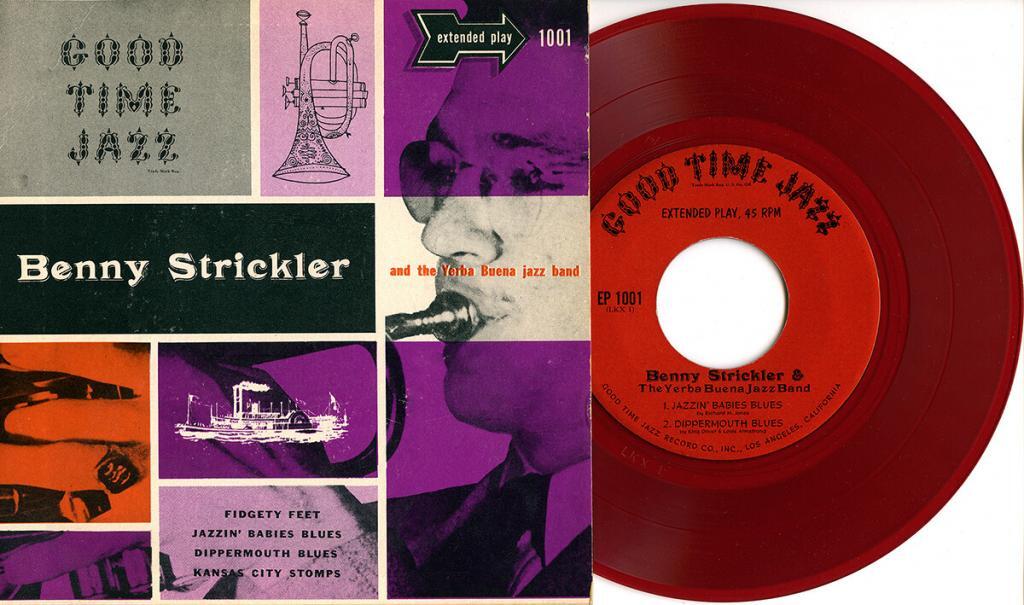

In 1942, he substituted for trombone player Turk Murphy in the Lu Watters Yerba Buena Jazz Band by special dispensation from the musician’s union. Bill was on the legendary Dawn Club recordings with gifted but doomed jazz trumpeter Benny Stickler and part of the group backing Bunk Johnson, the rediscovered early New Orleans trumpeter during his 1943 San Francisco residency.

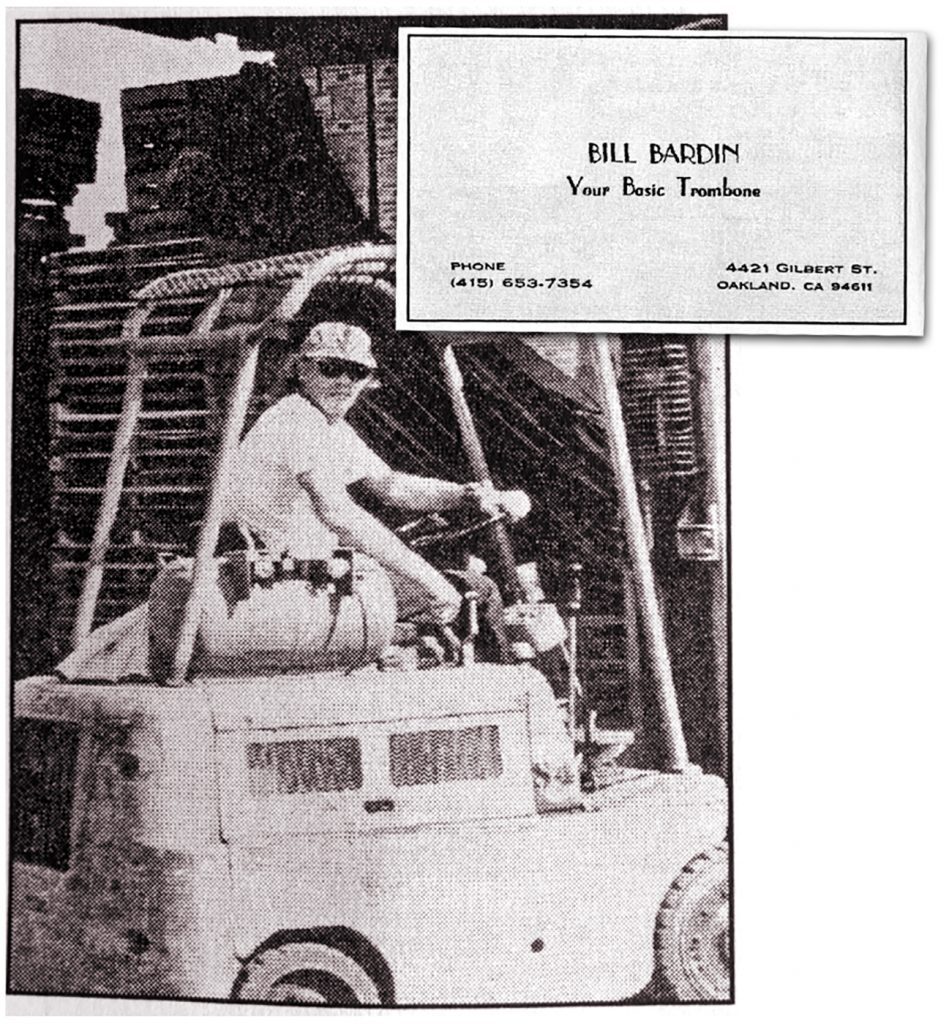

Bardin was among the Berkeley crew that launched Bob Mielke and The Bearcats Jazz Band in the mid-1950s, serving as Mielke’s only alternate. Around 1960 he was performing in Oxtot’s groups with Louisiana-born clarinet player Frank Big Boy Goudie. During the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s, Bill was integral to the bands of Dick Oxtot, P.T. Stanton, Earl Scheelar and others even while maintaining a non-musical day job, examined in part two.

Despite a music career spanning six decades, Bardin made almost no commercial recordings. Yet fortuitously, large swathes of recovered live recordings are offered below and at the JAZZ RHYTHM Bill Bardin page.

Benny Strickler at the Dawn Club, 1942

The Dawn Club in San Francisco (1941-46) was epicenter of the West Coast Traditional Jazz movement and home base for Lu Watters’ Yerba Buena Jazz Band. They rejected the romantic popular music of the large Swing orchestras in favor of the stomping two-beat Jazz of the 1920s. Playing raucous Classic Jazz, the Watters band had a huge impact on the musical tastes of American soldiers passing through Frisco headed to or from the Pacific war and a generation of San Franciscans.

Benny Strickler (1917-1946) was a gifted jazz trumpet player from Arkansas who had minor success in Los Angeles and with touring dance bands. Shortly before Frisco, he’d worked for an intense year with Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys at the apex of popular success. Benny had been ‘straw boss’ of Wills’ eight-piece horn section when they broadcast out of Oklahoma, recorded in Hollywood and smashed ballroom attendance records up and down the West Coast.

Clip 6 Strickler YBJB, Dippermouth, Berkeley band

Trumpeter Strickler:

“He was a big, friendly guy. Very helpful. He just wanted to help people to make a good sound, to get a good band sound. Very swingy bouncy trumpet. Compared to Watters his sound was lighter and bouncier. Benny Strickler knew how to place his notes so that the whole band would swing when he was playing.

Clancy [Hayes] liked to play the afterbeat cymbal a lot and Clancy was a great one for swinging too. They made a great pair. Knowing that Clancy was going to play afterbeat cymbal on two and four, then Benny might start a solo by playing on one and three. So, you would get this piston effect, so to speak.”

Strickler was familiar with Bob Helm and some of the Yerba Buena gang. In late Summer 1942 he was brought to the Dawn Club as a stand-in for Watters, who was serving in the United States Navy. Likewise, Bardin was standing-in for Turk Murphy and Burt Bales for piano player Wally Rose, both also serving in the navy.

Tragically, within weeks of arriving the twenty-five-year-old trumpeter became too sick with advancing tuberculosis to carry on, hemorrhaging through his horn as he struggled to play. Benny departed San Francisco by train under a doctor’s care, never to perform again, dying five years later. Recordings of Strickler and Bardin from the Dawn Club cemented forever their niches in the Traditional Jazz pantheon.

Jazzin’ Babies Blues – Strickler YBJB 1942

Kansas City Stomps – Strickler YBJB 1942

Emulating Yerba Buena:

“It was a wonderful experience hearing the Watters band in person. It was impossible to carry on a conversation they were so loud. But they were rich; they had a big, rich, round sound.

And some of us Berkeley people had set up a little band. It was with P.T. Stanton and Pete Allen and a few others . . . Someone in our band asked permission to play a set at the Dawn Club. So, we did, and we surprised everyone. Those guys didn’t know that anyone was doing that kind of music. They didn’t know, in short, that they had any imitators.”

Regarding Turk Murphy and Bunk Johnson

Jazz trombonist Turk Murphy (1915-1987) was a co-founder of Yerba Buena Jazz Band and the West Coast Traditional Jazz movement. He was a notable influence on Bardin’s early playing, but it’s complicated. As Bill put it, “I started as a Dicky Wells fan. Still am. Then I became aware of Turk and became a Turk imitator. I believe that I can safely say I am the first of the Turk imitators. And I no longer am.”

At the outset of the Second World War, Murphy enlisted in the U. S. Navy as a skilled musician. He was stationed nearby for a while and often given leave to perform. Yet throughout the war, Bardin (and others) subbed for him in Yerba Buena as needed.

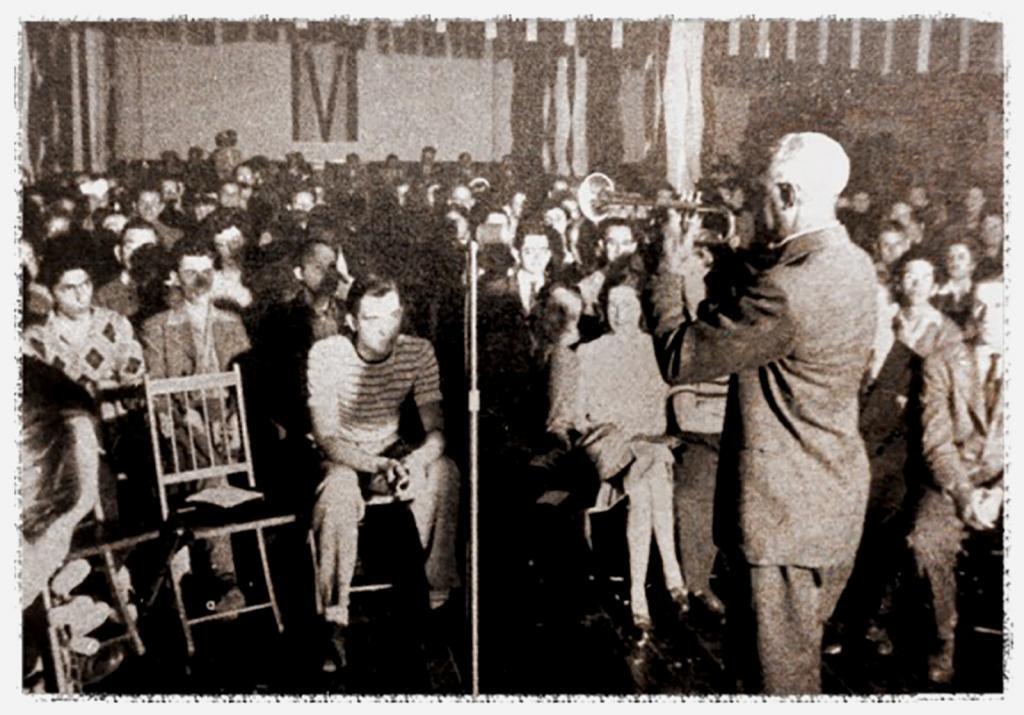

Bill was engaged again for a similar group backing Bunk Johnson (1889-1947), the rediscovered early New Orleans trumpeter. Bunk’s Sunday afternoon concerts in late 1943 were hosted by the Hot Jazz Society of San Francisco at CIO Hall (Congress of Industrial Organizations, America’s largest labor federation).

Johnson Kicked Off:

“He would start the tunes by kicking off, literally kicking off. By stomping his heel on the wooden floor twice, on beats one and three. Just one bar and we’d start playing. And then to end the piece, to let us know when we were about to end it, he would give two stomps of his heel but out of time, about eight bars from the end. And that way we’d know we were going to quit.

There was no dancing at the CIO Hall when Bunk as playing there. The floor was completely covered by folding chairs. Later when [Kid] Ory was there, there was plenty of dancing, but not in ’43.”

Bardin recalled that the roster for Bunk’s CIO Hall band included “Ellis Horne clarinet, Burt Bales on piano, Pat Patton on string bass or banjo, sometimes Girshback on tuba or string bass, Bill Dart on drums. I think sometimes Clancy [Hayes] played drums . . . and me alternating with Turk.”

The re-emergence of Bunk Johnson, a Golden Age trumpeter who dated back to the era of Buddy Bolden, galvanized and accelerated the nascent New Orleans Jazz Revival. Bill notes that prominent musicians visiting San Francisco dropped by — Count Basie, Jack Teagarden and Duke Ellington — “just to hear what Bunk sounded like.”

Bunk’s Ways:

“When I have read about Bunk and his behavior in books . . . he sounds like a different person entirely than the man that was out here in 1943. He seemed eminently reasonable, easy to deal with, easy to get along with. Collected.

One thing about Bunk; when there would be an important occasion like an around-the-world broadcast by the BBC, well, Bunk didn’t show up for this. He finally did stumble into the studio really drunk, in no condition to play and far too late to do any playing even if he were in condition to do so. There was another time, an important occasion when he didn’t show up until too late and he was too drunk to function.

He was great, in full control of things on the unimportant occasions. But if it was going to attract attention, or the attention of important people, Bunk seemed to prepare himself too fully, so he wouldn’t be nervous.”

Clip 7 Rooming at Ma Watters’ House

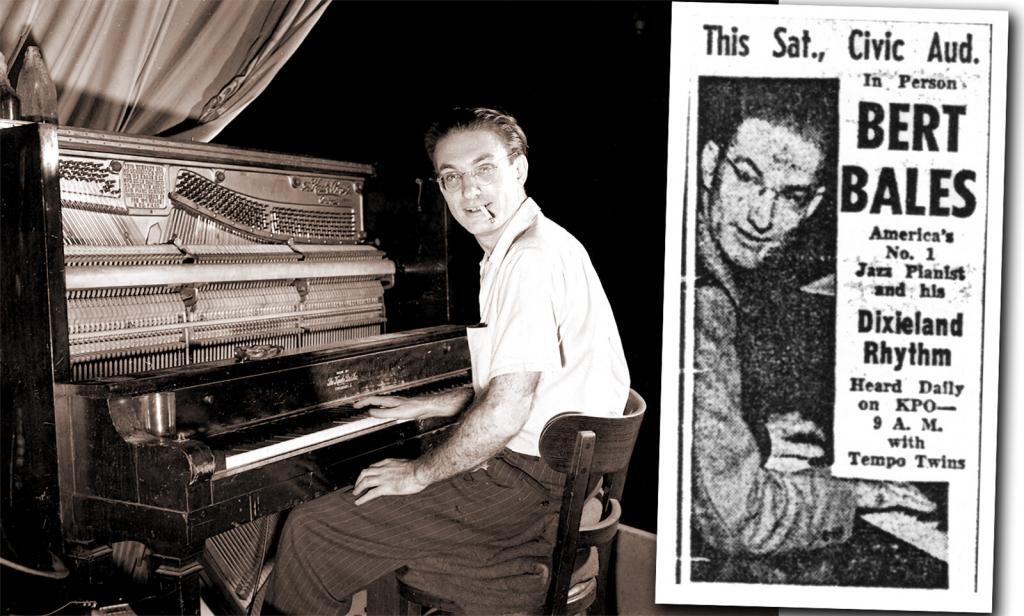

Buddies with Burt Bales

Residing in San Francisco into the early 1950s, Bardin lived just around the corner from piano player Burt Bales (1916-1989). Bales was almost certainly the most gifted Classic Jazz piano player to emerge from Northern California.

Bill heard him play solo and band piano at the 1018 Club on Fillmore Street, sometimes joining the casual band. He loved spending afternoons at Burt’s nearby apartment listening to records, entertained by his heterodox views: “a wiggy guy [who] had original ideas on political matters. My impression was he had a rather high IQ.”

Bales at the 1018 Club:

“Most of his career was as a solo piano player at the 1018 and Tenderloin places. The 1018 Club was a big square room lined in white tile like a bathroom. And Burt had a pedestal in the middle of the room, as I recall. Or maybe off to one side. Burt would sit up there and ask from time to time if anyone was going to buy the piano player a drink.

There was a piano about three feet off the floor on a small platform. He’d play his marvelous stuff; he was at the top of his form then. He would play Fats’ stuff. And he would play Jelly Roll. ‘Sweet Savannah Sue,’ tunes like that, ‘Original Rags.’

Everybody got along fine with Burt. Burt was very easy to get along with, very accommodating, very friendly. A really great guy.”

Clip 8 Hanging out with Burt Bales, 1018 Club

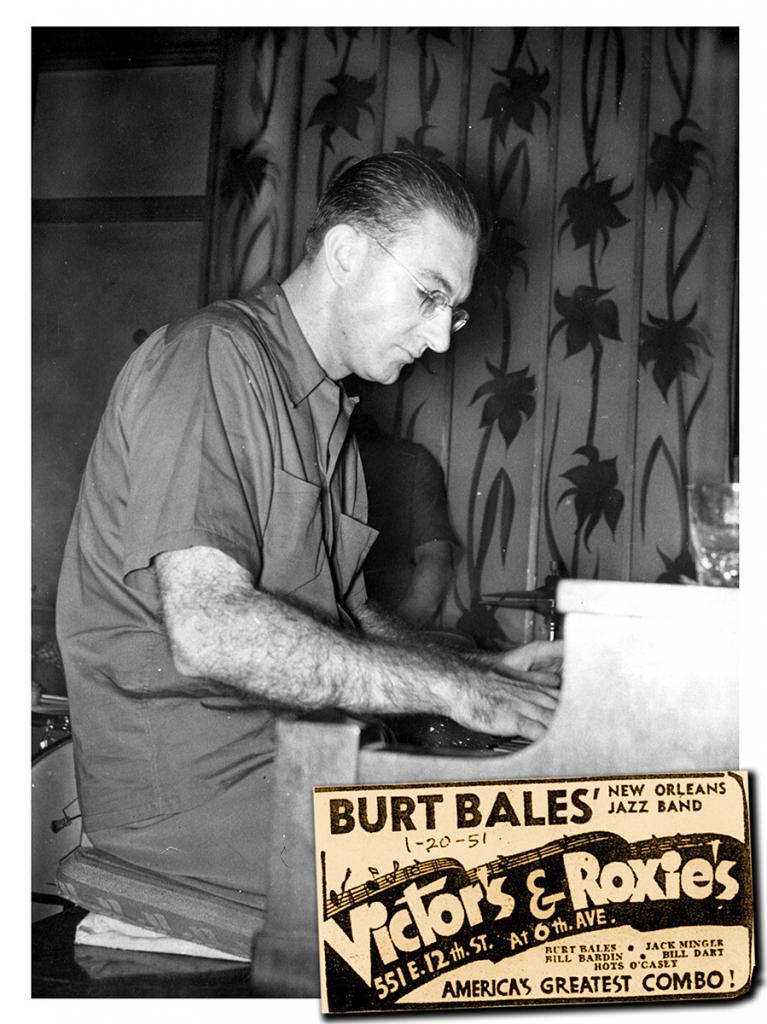

Music at Victor’s and Roxie’s

Victor’s and Roxie’s was a hotspot for Revival Jazz in Oakland from 1950 to ‘57. Bardin performed there with good bands assembled by Burt Bales and reed master George Probert. Bill soon moved to the East Bay permanently.

Victor’s & Roxie’s:

“It started as a neighborhood bar. . . and there was a coffee shop type restaurant connected to it; a long bar with a bandstand at the end of the room. It had booths with padded seats and scrim hanging from the ceiling – a sort of drapery. I don’t know who played there originally, probably a Country and Western band.

Scobey’s band played there for quite a while when Napier was with him . . . Scobey became quite successful there and well-known, so he started touring. And Burt took a band in. It had Jack Minger [trumpet], me, [Bill] Dart [drums], sometimes Hots O’Casey [clarinet]. When there were no conversations in the place you could hear the dull hum of the air conditioning and it was really depressing.

[Burt] had so many accidents. Setting himself on fire. Falling down the front steps. At Victor’s and Roxie’s one time I recall he was playing with a big cast on his left forearm. He had broken his left forearm some way or other, but it didn’t slow him up at all. He was playing his boom-chuck, swinging this immense weight back and forth and just keeping up with things. It must have taken a tremendous effort.

It was operated by a guy named Victor Long whose real name was Longo. He and his brother Johnny – they got along O.K. There was a third brother, Roxie. They had been partners and had a quarrel. Roxie opened his own bar somewhere else in Oakland.”

Eclipsed by Mielke

There was a natural but friendly competition between Bardin and Berkeley trombone player Bob Mielke (1926-2020). Bill was shy and self-effacing. Bob had a big personality, ran his popular Bearcats Jazz Band and enthusiastically promoted his gigs, casting shade on Bill.

Yet Bardin was Mielke’s understudy and only substitute in The Bearcats Jazz Band. And Bill was again alongside his old friend, cornet player P.T. Stanton, effectively The Bearcats’ musical director.

Both trombonists performed with bandleaders Earl Scheelar and Ted Shafer regularly at festivals, casuals or Traditional Jazz events and with singers Barbara Dane and Barbara Lashley. They were a duo in Dick Oxtot’s Golden Age ensembles. And in fact, their musical roles were often interchangeable or overlapping, as Bill explained, “Mielke and I have always sat-in on each other’s jobs. I used to think of my entire career as subbing for Mielke.”

Understudy to Mielke

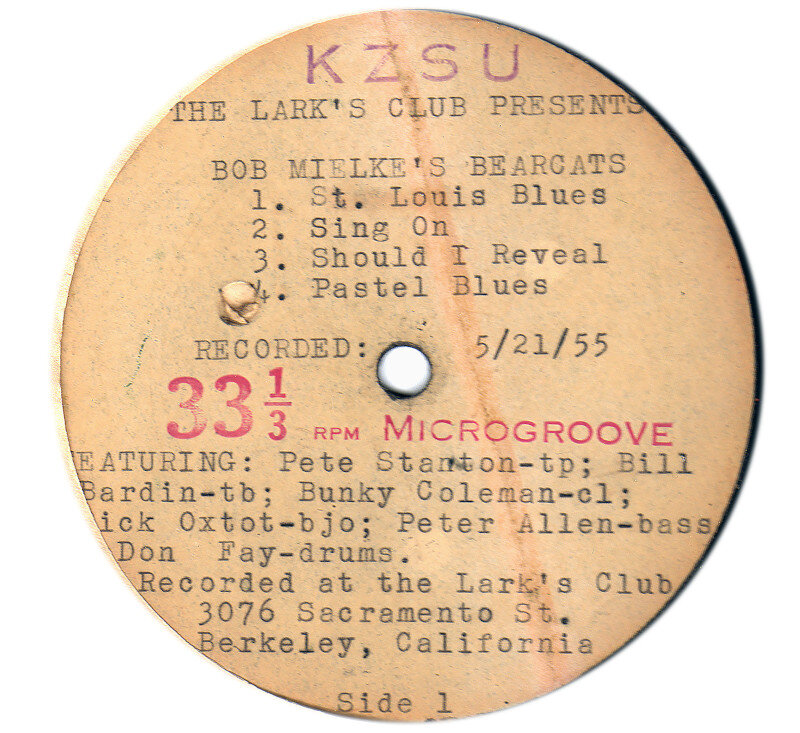

Bardin was no interloper in The Bearcats Jazz Band. He was Bob’s understudy, only substitute and legend has it that on occasion they performed together at the Lark’s Club. Here’s Bardin subbing for Mielke at the Lark’s Club with Stanton and The Bearcats Jazz Band, 5.21.55. Compared to Bob, Bill had a less assertive manner and a rolling, more rhythmic style. Note the insistent throbbing New Orleans Revival four-beat sound which was then emanating from veterans of the Louisiana diaspora like clarinetist George Lewis and trombone player Jim Robinson.

Saturday Night Function – Bardin Bearcats Larks Club

My Gal Sal – Bardin Bearcats Larks Club

Ice Cream – Bardin Bearcats Larks Club

Bill and Big Boy Goudie

Bardin also considered himself lucky to have performed with clarinet player Frank “Big Boy” Goudie (1899-1964), mostly in the ensembles of Dick Oxtot around 1960. A Louisiana-born Creole, Goudie had an astounding globe-spanning backstory threading through France, Europe, Mexico and South America, previously explored in three articles.

Goudie’s distinctive clarinet style had a rich husky tone and flowing lines, reflecting his New Orleans roots, decades playing tenor saxophone in Europe and advanced musical skills. Nearly six and a half feet tall and almost twice the age of these musicians, Frank spoke with a strong French accent, wore a beret and was by all reports a gracious Gentleman of Jazz though, noted Bill, “none of us called him Big Boy.”

Frank Goudie:

“A player who definitely ‘had it.’ Who would never let anyone down. He had a French air. He wore a beret. He played all over the world and he spoke with a French accent.

He was great at playing runs of even unaccented eight-notes; as contrasted with dotted eighths and sixteenths, flowing and unhurried. Never a crowded hurried sound . . . Again, he was very strong personality which came through in his playing. He wasn’t going to let anyone rush him or drag him.

When he was here in the City he had business cards. But it didn’t say ‘musician,’ it said ‘upholsterer.’ I understand that all the New Orleans guys, most them had trades. The other thing I remember is that . . . he told us we were better than we realized.”

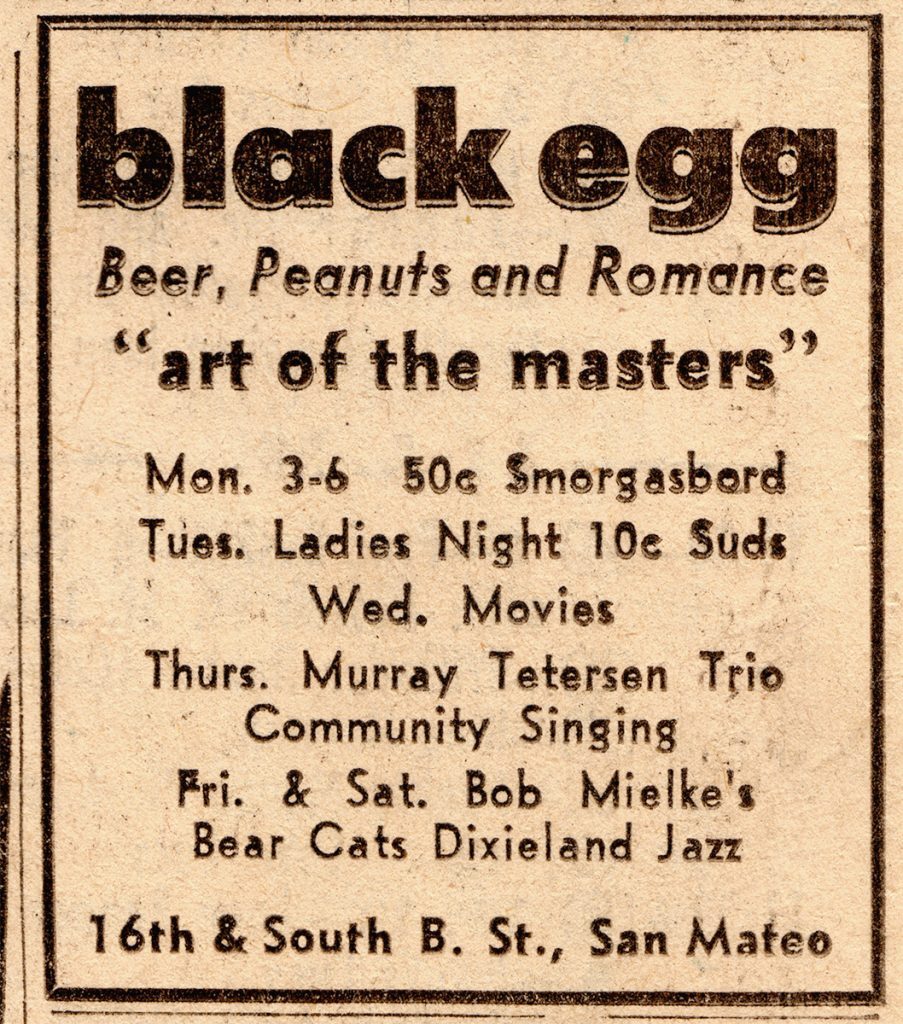

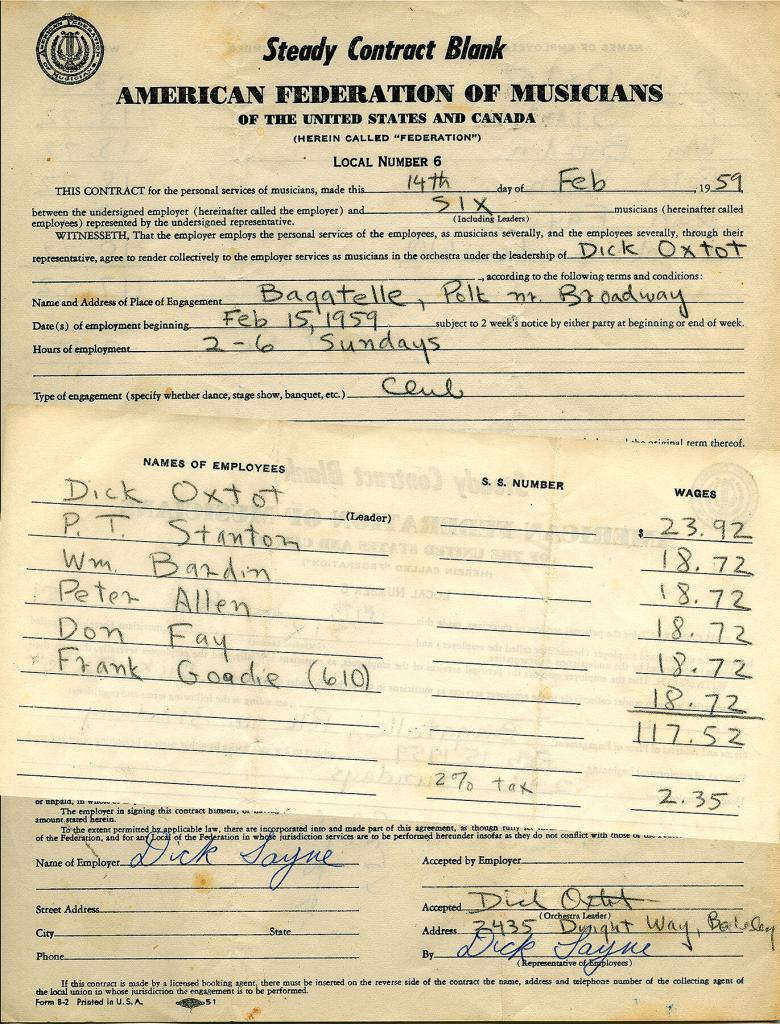

With Goudie and Oxtot at The Bagatelle and the black egg, 1959-60

Bardin was an essential component of Oxtot’s band at a San Francisco bistro called The Bagatelle. On Sunday afternoons Dick featured Louisiana-born clarinet players Clem Raymond or Frank “Big Boy” Goudie.

Walking into the bar in 1959, trombonist Jim Leigh (1930-2012) was electrified by the ensemble, as described in his self-published jazz memoir Heaven on the Side (2000). He immediately perceived Goudie’s remarkable qualities but wrote that it was Bardin who “blew me away entirely.” Jim was profoundly impacted by Bill’s “elegantly spare and rhythmic style,” finding in his condensed technique “another way to go.” They became great friends.

Goudie also spoke highly of Bardin, telling Ken Mills in a 1960 interview (Music Rising, Tulane University): “You could set him down anywhere in the world and he would be somebody to watch out for. Never mind if he doesn’t have a big name and a lot of records. A musician like that you got to DEAL with him. Hear four bars and you know two things: he knows what he’s doing, and he means business.”

This session is a 1960 Oxtot band at the black egg in San Mateo, a suburb on the San Francisco Peninsula some 20 miles South of the city; Mielke also played there. Besides Bardin and Goudie, the lineup included P.T. Stanton (cornet), Dick Oxtot (banjo) and Pearl Zohn on piano, supplying a basic steady boom-chuck rhythm pattern.

Pearl might have been the sister of the Zohn brothers — trumpeter Al and trombonist Joe. This may be her only extant recording and sole evidence of her participation in the Frisco Jazz Revival.

When You and I Were Young, Maggie – black egg 1960

I Want a Little Girl – black egg 1960

Milneberg Joys – black egg 1960

Co-operative, Adaptable and Expressive

Bill was a gentle soul – thoughtful, modest and well-spoken. Though perennially eclipsed by Mielke, his trombone parts had great depth, range and eloquence, unifying and uplifting any ensemble. Rising to the occasion in frequent encounters with greatness, Bill Bardin was at the center of the San Francisco Traditional Jazz Revival.

Taking a Day Job:

“I thought I was a professional musician. I was drinking too much. I don’t remember if the ‘dime jig’ was my last steady playing job or Victor’s and Roxie’s . . . But I didn’t have a paying job. So, I went to work in a warehouse temporarily in Richmond [1957] and that temporary job stretched into decades.

I was a day-worker taking casuals when I had the chance to . . . and occasionally being hired first call. I played a couple of times at [Club] Hangover — with Hines a weekend and with [trumpeter] Marty Marsala.”

Part Two continues Bill’s story through the 2000s, further exploring his evocative 1994 interview, rare performances and integral role in the bands of Dick Oxtot, P.T. Stanton and Earl Scheelar.

Meanwhile, these broadcast tributes to Bill (and list of contents) are found at the JAZZ RHYTHM Bill Bardin page.

Bill Bardin Pt. 1A

Bill Bardin Pt. 1B

Bill Bardin Pt. 2A

Bill Bardin Pt. 2B

Sources and Notes

Thanks to the late Mili Rosenblatt Bardin for photos, audiotapes and background. Bill was interviewed in 1994 in co-operation with Bill Carter and the San Francisco Traditional Jazz Foundation. Bardin Bearcats tape courtesy of Oscar Anderson. Ken Mills’ 1960 interview of Frank Goudie is at the Music Rising website of Tulane University.

Emperor Norton’s Hunch, John Buchanan, Hambledon Productions, 1996

Jazz West 2, K.O. Eckland, Donna Ewald, 1995

Heaven on the Side, Jim Leigh, self-published, 2000

Bay Area Jazz Clubs of the Fifties, Bret Runkle monograph, Berkeley Public Library, 1978

“Strickler Family Album Epilogue [interview Helm and Bardin]“, Hal Smith, The Frisco Cricket, Summer 2002

“Benny Strickler: Legendary Trumpet Stylist,” Hal Smith , The Frisco Cricket Fall 1998

Bardin made very few commercial recordings, but many recovered performances may be found at the JAZZ RHYTHM Bill Bardin page and are preserved in the Dave Radlauer Jazz Collection at the Stanford University Libraries.

Links at Stanford Libraries:

Links at Jazz Rhythm:

Strickler – Frisco

Strickler – Tulsa

Dave Radlauer is a six-time award-winning radio broadcaster presenting early Jazz since 1982. His vast JAZZ RHYTHM website is a compendium of early jazz history and photos with some 500 hours of exclusive music, broadcasts, interviews and audio rarities.

Radlauer is focused on telling the story of San Francisco Bay Area Revival Jazz. Preserving the memory of local legends, he is compiling, digitizing, interpreting and publishing their personal libraries of music, images, papers and ephemera to be conserved in the Dave Radlauer Jazz Collection at the Stanford University Library archives.