Recently, I went back to Medford, Long Island, to revisit the box of papers that once belonged to Fred Hager. While yes, I did go through them six months ago, I wasn’t able to spend sufficient time really studying what I was looking at. After this recent visit, I was able to discover new things and come to curious conclusions. I spent nearly six hours late into the night going through these papers, but could easily have spent more.

Something that I have previously noted in past articles is how many beautiful manuscripts remain in this small collection. Fred Hager was completely capable of writing music; in fact in my collection I have a few small pages he penned, but he generally didn’t spend the time to do it. Hager’s writing can be observed on the many hundreds of discs that Zon-O-Phone issued between 1900 and 1902, which at times can be difficult to read, but are very distinct in style. Decades later he sometimes used this same print.

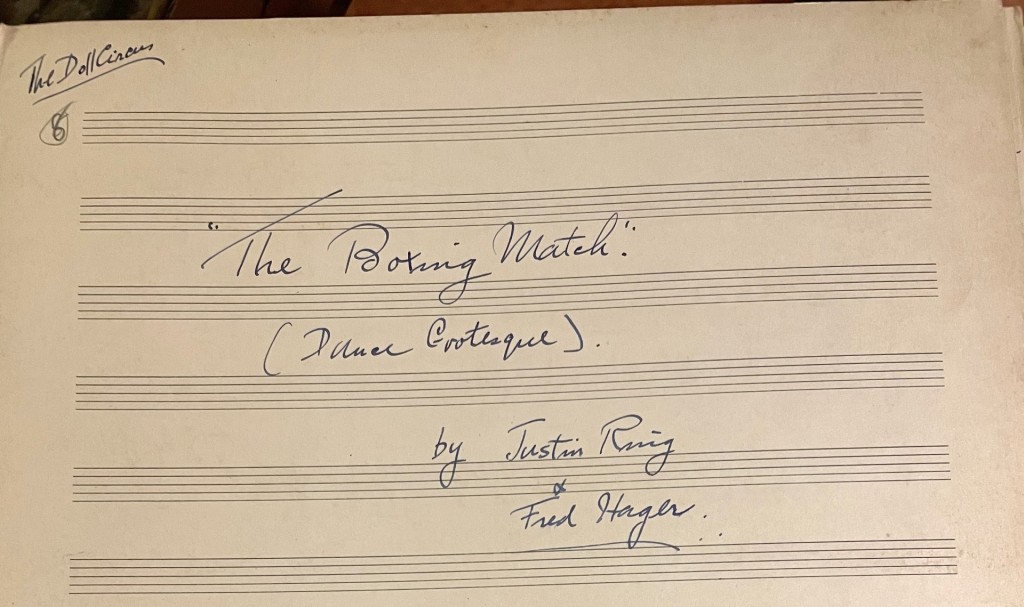

Many of Hager’s ideas were dictated by Justin Ring, even beyond written music. At some points while going through these papers I found it difficult to distinguish Fred’s and Justin’s writing. Hager seemed to write notes on any piece of paper he could find at the moment. It seems there is a lot more of Ring’s writing in these papers than I had previously thought. These manuscripts are among the most elegant and neatest of any I have ever seen, and beautifully bound in red cardboard. Surely being in Hager’s orchestra and getting handed these pages wouldn’t at all be difficult to read.

It shouldn’t be much of a surprise that Hager kept not one, two, but four different manuscripts of his and Ring’s “I’ve Got My Eye on You,” which was the first song the two of them wrote together. Clearly the piece was important to both of them. Two of the manuscripts appear to have been the first of the piece, dating to 1901 as one of them (it isn’t certain which) indicated at the bottom. It is therefore likely that these two manuscripts were used in the Columbia, Zon-O-phone, and Edison recording labs by their musicians. They are the same size as standard sheet music of the period, and one of them is mysteriously burnt on the top corner. He also kept a tattered copy of the published sheet music. It also ought to be noted that the envelope Fred kept these manuscripts in had a penciled in: For Mr. Hager. This was certainly written by J.R. as he often signed his name on these pages. It is important to note that Hager had kept these pages for decades by the time they were stored together in this box. Only the most significant things stayed with him for so long.

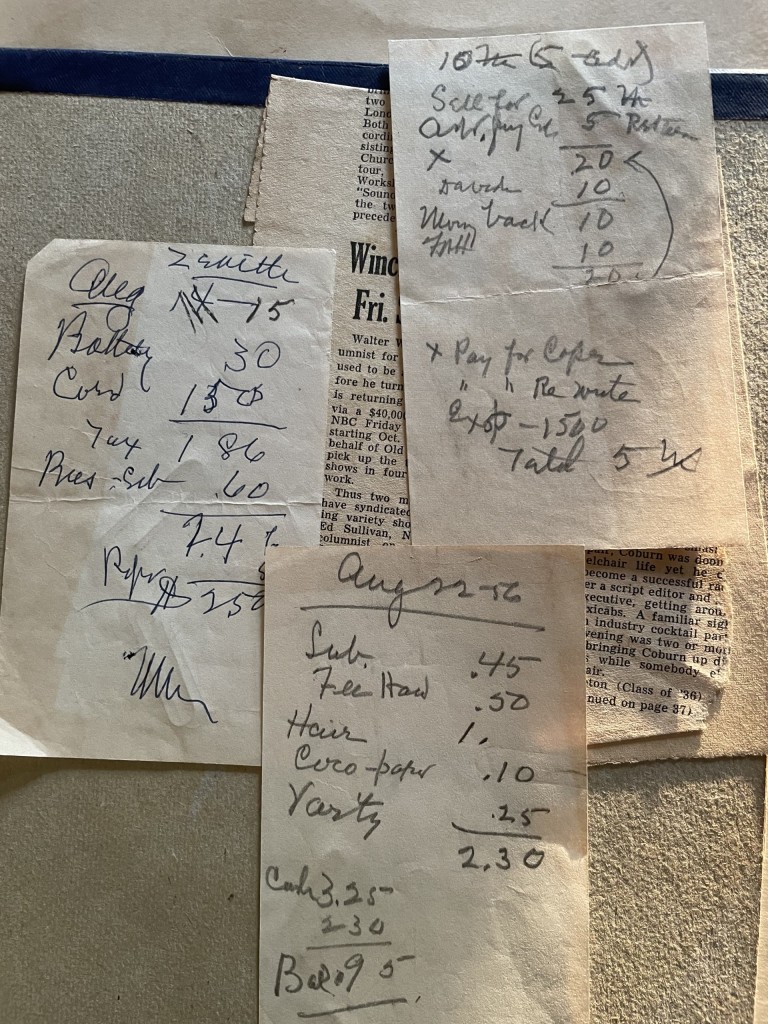

While we can be almost sure that Ring and Hager’s relationship was intimate in some way, Ring also described Hager as his “Promoter,” and depended on him to handle the more intricate aspects of working in the music business, and at this he excelled. A good portion of what is left in this box of papers is related to the fine details of copyrights and royalty calculations. Countless pages contain Hager’s chicken scratch doing math, and making sure that all his materials were giving him and Justin appropriate royalties. When the numbers didn’t work out, he made sure to voice his concerns to the publishers, writing to as many of them as he could.

As his great-nephew has indicated several times, Fred was strident in his dealings with music business matters, up until his dying day, going into Manhattan and interfacing directly with ASCAP. It must be noted that the misdeeds of Hager’s younger days are part of the reason that ASCAP was organized in the first place. Victor Herbert sued Zon-O-Phone in 1904 for illegal use of his name on their label, which was almost entirely Hager’s fault, giving Herbert one more reason to found ASCAP a few years later.

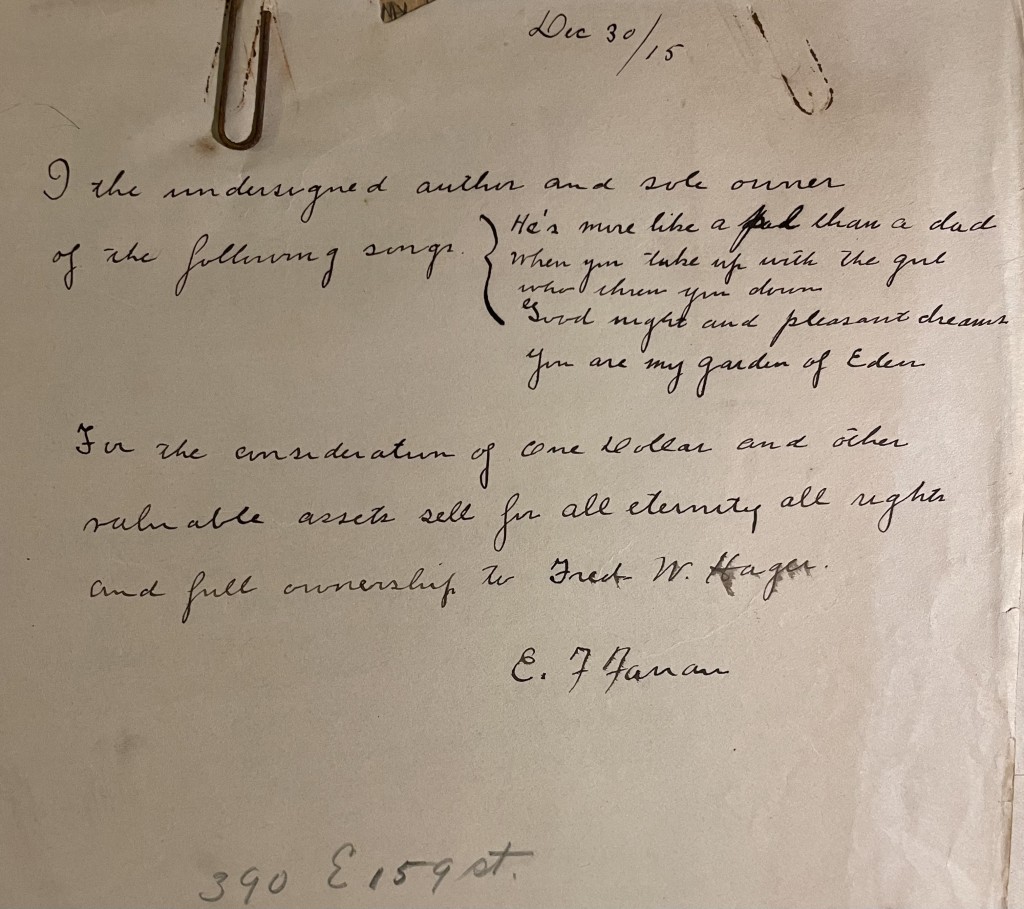

By all these documents, Hager was a rich man in royalties. Something that he kept mostly to himself, Justin Ring, and maybe his wife Clara. Going all the way back to his 1903 “Laughing Water,” Hager was receiving royalties adding up to thousands by 1908. Not a single opportunity for extra money was skipped, and whenever things didn’t calculate to his liking, he took them to court. Not a single piece he was involved with in any sort of way was missed. He took special care of pieces he published with J. Fred Helf, who had since died in 1915 (it is likely that he also received much of their estate). Dozens of papers regarding royalty amounts survive in this collection. Hager even made detailed lists of all the pieces he had under his ownership, so he could keep track of every one. Each of these lists was also signed off on by Justin Ring, assuring that these were all the correct numbers. It seems that everything had to be double checked by J.R.

Even though he retired from recording in 1923, he remained a very busy man on the radio. In the late ’20s to early ’30s, he managed the radio career of the Green Brothers, who he had worked with back at Okeh. He kept a few pages of correspondence regarding them, including a historic photo of the band recording for NBC. By the mid 1930s, Hager was the radio manager for the famous composer Rudolph Friml, and of this he was very proud. The local Flushing paper noted Hager for his knowledge of the radio world, and of his intimate knowledge of Friml. He was answering everyone’s questions about radio, it seemed.

Another thing Hager did a lot of was typing proposals for various media. In my own collection of Hager’s material, I have two of these proposals. They are essentially small screenplays and sketches for radio or television. Like many folks of their generation, Ring and Hager were fascinated with television. They even wrote music about the new technology. As early as the mid 1940s they were writing short pieces and sketches intended to be pitched for the new medium. Though they were essentially at the end of their career, Hager was determined to get into television somehow. In this collection there were several proposals, one about a couple running through all sorts of antics in a recording studio (sounds awfully familiar in a way), and a few acts illustrating his and Ring’s songs. It is unclear if any of these proposals made it onto the radio or television, but most of them likely didn’t. Hager saved several rejection letters from media companies, which are, in a way, entertaining to read. One of these from 1940 reads:

Your game sounds very interesting but at the present time we have no place for an extra program and do not feel that it could very well be incorporated into any of the shows we now have on the air…

Most of them read like this.

He continued to write to media companies even with these rejections.

It seems essential to note a few cameos and name drops in these papers, as in this second comb through, I noticed some names I didn’t catch last time. Other than Elvis, Rudolph Friml, and Gene Krupa, it ought to be noted that Hager corresponded with the Berliner family.

Unfortunately all of the direct correspondence Hager did no longer exists, for reasons that might involve his relationship with J. R. The only indication of his correspondence with the Berliner family is a tiny piece of torn paper with the typed address of H. S. Berliner of Quebec, undoubtedly one of the famous disc record family. To add to this discovery, paperclipped to that very scrap is another listing Jim Walsh’s address, and a few penciled in pieces to send to him. Hager also saved a few papers acknowledging a few copyright deals with Edgar Farran, a figure that came between him and Ring around 1906, and remained composing with them until about 1918. There was even a single mention of Ralph Peer, who he may have had a falling out with when he resigned from Okeh. Peer himself very rarely, if ever, mentioned Hager in his writings, possibly indicating some kind of tension.

A lot more could be said about these papers, as I will need even more time to fully process what is in there. This small box is only a fraction of the material that Hager once had, but the fact that any of it survives is remarkable. I must note that many of these pages are also in very good condition, as they were kept basically sealed in a trunk for decades, untouched for nearly half a century. I will be back again to see them soon. And yes, if you have been wondering, I do plan to write a book about Ring and Hager when the time is right.

R. S. Baker has appeared at several Ragtime festivals as a pianist and lecturer. Her particular interest lies in the brown wax cylinder era of the recording industry, and in the study of the earliest studio pianists, such as Fred Hylands, Frank P. Banta, and Frederick W. Hager.