Jeff Barnhart is an in-demand solo performer, sideman, bandleader and festival musical director with a well-deserved, international fan base. Besides sharing a bandstand with this writer on many occasions, we also share a passion for the music of Fats Waller.

Jeff performs Waller’s music on a regular basis and has resurrected some extremely rare Waller compositions from the early 1920s. One of them is “Please Tell Me Why?” which was recorded only once (in 1924). Another, “Every Sweetie That I Get,” was literally reconstructed by Jeff (adding appropriate chords to an existing melody and lyric sheet found in the Library of Congress). Jeff also made the first and only recording of that particular song.

Currently, Jeff leads the Fats Waller Legacy Band (available with either American or European musicians). The FWLB performs the rarities mentioned above, in addition to songs associated with Waller throughout his career and even some Waller-inspired original compositions.

I have been a Fats Waller fan since my exposure to the RCA Vintage Series “Valentine Stomp” album in the late 1960s. Almost 30 years later, I was able to record an album of seldom-heard Waller compositions for Jazzology with the “Rhythmakers,” featuring the wonderful vocalist Rebecca Kilgore. More recently I have been privileged to play drums with the American edition of Jeff Barnhart’s Fats Waller Legacy Band.

As Fats Waller mavens, Jeff and I hope that our comments on a few of our favorite solo piano recordings by “The Harmful Little Armful” will stimulate the readers to check out his music. LATCH ON.—Hal Smith

HS: Jeff, You may not be aware of this, but I am a sucker for Novelty style piano. One of the first Fats Waller solos I heard was “Gladyse.” The first two strains could almost have been written by Felix Arndt—if he had grown up in Harlem. But Waller’s dynamic playing on the last chorus (especially on the second take) is some of the best stride piano I have ever heard. What are your thoughts regarding this record?

Jeff Barnhart: I didn’t know that about you Hal, but I’m not surprised. The rhythms of novelty piano turn on any ears in search of syncopated scintillation. The next time we’re performing together, let’s dust off a few of those novelty numbers, perform them and then retire for a long nap… LOL.

As a quick aside, the stride monsters generally eschewed the novelty style as a rule. With notable exceptions such as James P. Johnson’s “Jingles” and Willie “The Lion” Smith’s “Conversation on Park Avenue” (and to a lesser extent, his “Rippling Waters”) you don’t find too many examples of stride pieces containing healthy doses of the characteristics found in the Novelty style. This is one reason I’m so glad you brought up “Gladyse,” and reminded me that Waller did two takes.

My fascination with “Gladyse” is two-fold. First, other than segments of “African Ripples” (essentially a sped-up “Gladyse”) and “Smashing Thirds” we find little Novelty style piano in Fats’ solo piano compositions. Second, it is illuminating to be able to hear two takes of the “same” piece; you alerted me how dissimilar are the two takes of “Valentine Stomp” as well.

We should take a moment to discuss the term “set piece” when describing the works of the stride monsters. A “set piece” would be one that underwent little variation from performance to performance or recording to recording. The older stride pianists, such as James P. Johnson, would tend to stick with the original version of their compositions, as in “Carolina Shout,” “Harlem Strut,” “Keep off the Grass”(compare 1921 & 1944) and so forth. Whether because Fats was younger, less disciplined, more “in his cups,” or any combination of the three, we find few “set pieces” in his oeuvre, perhaps limited to his “Handful of Keys” and “Viper’s Drag.”

That notion of “set piece” is obliterated by comparing the two takes of “Gladyse,”which brings me to the flipside of my love for this piece. I enthusiastically agree with your description contrasting our two “Gladyses” (Gladyii? What’s the plural??): “Take 1 is pleasant, but take 2 is ferocious.”

The first melody of both takes—16 bars long, hearkening back to the ragtime era—is almost the same but it’s remarkable how much the second section of the piece changes from one take to the next. Rhythmically, harmonically, texturally, Fats goes for the jugular in the second take, whether because he had a bit more of that “fine Arabian stuff” between takes or he just (any musician who records has been there) thought, “AGAIN? Alright—Here ‘tis..” In the first, widely available take, Fats’ playing is more accurate and contained, and much less exciting… Is there a way you could provide access to our readers to the lesser-known second take?

HS: Yes. First, I recommend that our readers search eBay, Amazon Marketplace, Discogs.com and CD and LP online for a copy of The Fats Waller Piano Solos: Turn On The Heat, a two-CD set released on the Bluebird label several years ago (# 2482—2—RB). This set has all of Fats’ solo piano records recorded commercially between 1927 and 1941, with several alternate takes. As we just commented, the difference between takes on Fats’ records can be astounding.

We should briefly mention that all the other selections featured in this column can be found on YouTube and listening to them while reading our discussion may greatly enhance the reader’s experience.

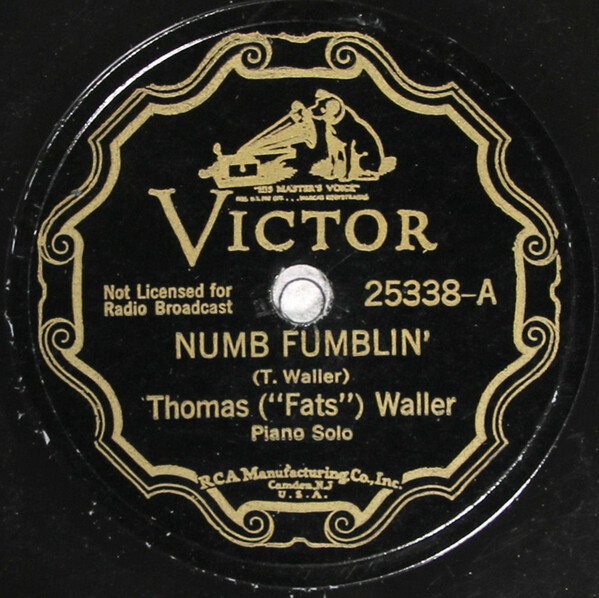

JB: You got it, Hal. Now, I’d love for us to discuss two of Fats’ recording of the blues, especially as he was never recognized as a performer or composer who introduced much blues feeling into his work. I think “Numb Fumblin’” and “My Feelin’s Are Hurt” will keep skeptics scrambling for a while. Are both or either of these pieces on your shortlist?

HS: “Numb Fumblin’” was recorded immediately after the wild band sides by Fats and his Buddies (“Minor Drag” and “Harlem Fuss”). Eddie Condon wrote about that session, where he played banjo, and was in awe of Fats even being able to play, much less turn out four masterpieces in one morning after an all-night drinking party. Besides the two band sides, Fats recorded the keystone version of “Handful Of Keys” and then “Numb Fumblin’”—which is anything but what the title implies. It is a real blues, and was played with authority. Compare this performance to Joe Sullivan’s records of his own compositions “Gin Mill Blues” and “Just Strolling,” and you will notice just how much Fats influenced the younger pianist. The beautifully-articulated arabesques on the last chorus of “Numb Fumblin’” are closer to novelty piano than the blues, but it’s a miracle that Fats was able to play them so cleanly—while he was probably so full of gin as to be flammable.

“My Feelin’s Are Hurt” has a completely different feel; closer to his early-’20s records, such as “Muscle Shoals Blues.” There is a well-played double-time section on the final chorus, but overall it is an excellent blues performance, without question.

You must be very fond of both of these records. What elements are most appealing to you?

JB: When you listen to these two blues improvisations back-to-back, it’s remarkable, though recorded six months apart in two different keys, how texturally and structurally similar these recordings (both six choruses long each) are—on the surface. In both recordings: the intros (four bars for “Fumblin’”; eight for “Feelin’s”) imaginatively whet our palates for the forthcoming delights; the first chorus of both treats us to some lovely harmonic extensions in bars 3-4; the second chorus of both features Fats’ trademark “walking tenths” in the left hand; chorus three of both begins with a marching left hand beat (a la Morton’s “The Pearls”) and at the end of both recordings we are treated to another of Fats’ thoughtful “dock the ship safely” endings. The similarity ends there.

“Numb Fumblin’” (key of C) is so delicate and sparkling, dripping with Wallerisms such as parallel thirds to start the fourth chorus and, throughout most of the sixth chorus as you mentioned, those cascading figures that no-one could do like Fats.

“My Feelin’s Are Hurt,” (key of F) on the other hand finds Fats abandoning the blues form and harmonic structure during the third 16-bar chorus and here we enter uncharted territory. In bars 8-12 of this third chorus, he treats us to a beautiful, wistful interlude in the relative minor key of Dm (one wonders if he preconceived the entire third chorus of this tune as a different section—perhaps a verse?) before returning to the stomping style.

The final three choruses are rife with seat-of-your-pants, rent-party-at-3-am HOT stride at a medium tempo, and you’ve mentioned how we’re treated to a “double-time” section in the final chorus. Shallow similarities aside, Fats’ two blues are unique in their results: “Fumblin’” leaves us numb with its ethereal beauty and “Feelin’s” leaves us breathless.

HS: I hate to let go of the 1929 recordings, because they are all favorites. But, I’m going to move forward to 1935, and a broadcast version of Vincent Youmans’ “Hallelujah.”

Fats phrases the first chorus as though he is singing with the right hand and accompanying with the left; very much like you would expect to hear in a musical. Then, on the second chorus, he begins striding away. But the feel is so light that it gives you the sensation that Fats is floating above the keyboard. (He may have been). He starts the third chorus with some staggered accents in the right hand for a couple of bars, but quickly switches to quoting from “Valentine Stomp.” On the final chorus he sets up a riff with the right hand as the left increases the intensity. There is a brief break in the left hand rhythm on bar eight, then back to the full force of both hands. He adds a few bars of glissandos with the right hand, then returns to the riff, using it to slow the tempo down for the ending. There is a rare recording of Fats playing “Hallelujah” in 1943—one of his last records—and he re-used some of the same ideas from 1935. They were worth repeating.

JB: (laughing)—great image, Hal…Fats “floating over the keyboard”…that’s gotta be one brave piano. Humor aside, anyone would be hard pressed to find a more apt phrase to describe his playing on the 1935 version of “Hallelujah,” a rendition you covered so beautifully that I’ll simply add a bit to your observations. That first chorus is definitely in the “show style” you’d hear from a pit orchestra; I emphasize that word for in addition to the melody and left hand accompaniment, Fats is treating us to numerous, textured counter-melodies, essentially playing an orchestrally scored version of the tune.

His full-on stride in the second chorus is remarkable in its lightness; no-one was bigger than Fats, and no-one could play smoldering stride with such delicacy: it reminds me of Snoopy carrying the soap bubble. The triplet figure that Fats quotes here from his own “Valentine Stomp” is a favorite for all stride pianists, past and present; it was Fats who took that “trick” and turned it into a fully realized piece. And why not? After all, he plays both versions of “Hallelujah” in the key of D, so it makes sense that the figure (and indeed, as you point out, most of the first section of “Valentine”) would creep in, at least to the earlier recording.

His recording from 1943 is really sui generis, however. I’d not heard this one before and it floored me. From his initial brief quotes of Handel’s Hallelujah Chorus, to the basso profundo statement of the opening motif of Youmans’ piece—accompanied by cherubic answers in the high register—to the show band playing of the bridge of the tune, to the final eight bars of the first chorus, where he returns to his call-and-response between hands, we are entering uncharted territory. The second chorus continues in the quasi-classical, stately mood set up in the first: flowing Debussyian cascades in the right hand over the unembellished melody in the left take us once again to a contrasting bridge, from which we emerge with another nod to Handel before the transition to Fats’ trademark “tripping along the keys” in pure stride.

Hal, what really amazes me regarding this track, is how Fats takes his time—we don’t arrive at a steady tempo (in stride style) until two-thirds through this 3 ½ minute performance. It’s also lovely to hear him humming along towards the end, urging himself to greater (pardon the pun) strides. An echo of the drama that began the performance wraps up this remarkable version of an old favorite.

Before I reveal my next choice, it might be a good idea to briefly touch on two stories about Fats. The more well-known one is how he would sneak into any church left open in the wee hours of the morning and play on the church organ (a Chicago critic once remarked that the piano was the instrument of Fats’ stomach, while the organ was the instrument of his heart). Perhaps less known was his behavior during some of the after-hours soirees in which he would inevitably find himself: he would sit at the keyboard, playing very much in the style we hear from the 1943 recording we’ve been discussing, and even noodle in the styles of classical greats such as Bach, Mozart or Beethoven, until someone inevitably shouted out, “OK, enough of that high-brow stuff, Fats, get on with the jive.”

There’s no question he was an improvisatory genius. To illustrate that, I’d like to bring his 1937 version of his seminal standard, “Keepin’ Out of Mischief Now,” to the table. You’d think it possible, having played it thousands of times, that Fats would have an array of stagnated figures on which to fall back, but this couldn’t be farther from the truth. Does anything stand out to you, Hal?

HS: The first chorus makes me think of how Fats might have played the song with his Rhythm group, or possibly on a transcription date. It sounds a lot more casual than you might expect on a solo piano record of his own composition, for a major company. There is a playful, chime-like introduction and some rhythmic hesitations in the first chorus. You can easily picture his facial expressions and imagine some vocal comments on this section too. Fats throws in a lot of characteristic licks—trills and triplet figures in the treble (I call them “sparklets”), some “baby elephant patter” in the bass, and using the lower and middle registers of the keyboard as a contrast to all the filigree in the treble. It seems like he played more ornamental figures than usual on this one, and the ending meanders a lot more than on most of Fats’ solo records. Overall, this side sounds a lot less focused than the other numbers from the same session. (Interestingly, “Keepin’ Out Of Mischief” was the only Waller original recorded at this date).

HS: The first chorus makes me think of how Fats might have played the song with his Rhythm group, or possibly on a transcription date. It sounds a lot more casual than you might expect on a solo piano record of his own composition, for a major company. There is a playful, chime-like introduction and some rhythmic hesitations in the first chorus. You can easily picture his facial expressions and imagine some vocal comments on this section too. Fats throws in a lot of characteristic licks—trills and triplet figures in the treble (I call them “sparklets”), some “baby elephant patter” in the bass, and using the lower and middle registers of the keyboard as a contrast to all the filigree in the treble. It seems like he played more ornamental figures than usual on this one, and the ending meanders a lot more than on most of Fats’ solo records. Overall, this side sounds a lot less focused than the other numbers from the same session. (Interestingly, “Keepin’ Out Of Mischief” was the only Waller original recorded at this date).

What elements of this recording appeal to you?

JB: For me, this track, perhaps more than any other solo Fats recorded, embodies the Pan-like spontaneity for which his personality more than his playing has been amply chronicled. Additionally, it is a text-book treatise on mid-tempo stride performance. That first chorus is chock-full of surprises, in terms of dynamics, texture and the hesitations that you referenced. One NEVER knows what’s coming next; he doesn’t settle down until the final 10 bars of the first chorus. He begins his second chorus with a descending triplet figure—a stride staple—and then these short cascading figures appear that are indeed, to coin your phrase, “sparklets.”

Sticking close to the melody in the first half of the third chorus, he lobs it back and forth between hands, some stomping parallel triads in the right hand, then chimes in the left with more “sparklets” in the right to bring us to a remarkably almost atonal transition to the final chorus; one feels Fats lost his way and found it back by the skin of his teeth. Ingenuity abounds in the final chorus, from the “baby elephant patter” style opening to a two bar SOLO walking-tenths bass line (perhaps he used this opportunity for a quick nip?).

I’ll finish by briefly discussing that ending you mention: those remarkable cascades across the keyboard first on a diminished seventh chord (F#, A, C, Eb), and then on first an Fm6 (F, Ab, C, D) to another diminished (B, Ab, F, D) sounds rather classical a la Chopin or Liszt at first hearing. However, by 1937 Art Tatum was all the rage in New York, having relocated from Toledo, Ohio five years previous and giving every Gothamite pianist agita. This ending might have been Fats’ gentle “nose-thumbing” at Tatum—“See, I can run lots of arpeggios, too.”

“Keepin’ Out of Mischief” is Fats at his most relaxed, in the least pre-planned playing possible, and we listeners are richly rewarded for this version of his standard having been captured and released.

Hal, it would be fitting if you would please select our final Fats solo to discuss, as you initiated our journey way back in 1929 (laughs). What tune would you like to wrap up with?

HS: I’m going to select Fats’ 1941 recording of “Carolina Shout” (the first take). This song goes back to the very beginning of Fats’ musical career, and the time spent studying with his mentor—James P. Johnson. It is one of the best-known stride piano features and is also one of the most frequently played. Johnson himself recorded the piece numerous times, but Fats’ version is the ultimate powerhouse performance. He acknowledged the composer’s original melody, but there are some characteristic Waller innovations throughout—and a few clams, too. While the second take is cleaner, and more concise, Fats took more chances on the first run-through and I think it is a more exciting performance. As stride piano scholar Mike Lipskin noted, Fats forgot to play the third theme of “Carolina Shout,” but the keyboard must have been smoking by the time he played those last few rambling notes.

JB: Man, what a STOMPIN’ way to end our first discussion. Fats’ final solo Victor date in 1941 will forever be a testament to what overwhelming talent can accomplish when unleashed and unfettered, and his “Carolina Shout” is PURE power. As a comparison, after I listened to Fats in ’41, I went back to James P’s recordings of “Carolina Shout” in ’21 and then again in ’44. The first thing that struck me is that my foot was tapping in two (on beats one and three of each measure) during the Johnson recordings and then in four (one tap for each beat in the measure) when Fats was laying it on us. Swinging better than any gate. Take one is surely the most exciting one and, true to the spirit of taking chances, most like what you would hope for in a live performance: in-the-moment, this-has-never-happened-before (and never will again) spontaneity.

Here is Fats at his most confident and at the peak of his powers. Just short of his 37th birthday, he’s pounding out this joyous, freight-train version of his mentor’s seminal stride masterpiece, no doubt thinking of nothing but endless good times, good music and good gustation. He would only be granted a little over two-and-a-half additional years on this earth. Fats provides a great lesson for all of us during these trying times: live every day as if it might be your last, with as much joy and gusto as you can. Because, one NEVER knows…do one?

HS: Jeff, this discussion has been a Gassa from Manassa and a Killa-Dilla from Manila. I really appreciate your informed comments on “Fatsy-Watsy’s” solo records, and now I have learned the proper terminology for a lot of stride piano techniques. I’ll look forward to talking with you again next month, and I propose that we take a look at recordings by the bluest of bluesy clarinetists: Johnny Dodds.

JB: That sounds terrific, my friend. Looking forward to it!

Visit Jeff Barnhart’s website (www.jeffbarnhart.com) and Hal Smith’s (www.halsmithmusic.com) for information regarding recordings and upcoming engagements.

Fats Waller Discography

Fats Waller: The Complete Recorded Works

Vol. 1: 1922 – 1929 JSP 927 (4 – CD set)

Vol. 2: 1929 – 1934 JSP 928 (4 – CD set)

Vol. 3: 1934 – 1936 JSP 946 (4 – CD set)

Vol. 4: 1936 – 1938 JSP 948 (4 – CD set)

Vol. 5: 1938 – 1940 JSP 949 (4 – CD set)

Vol. 6: 1940 – 1942 JSP 952 (5 – CD set)

Yacht Club Swing and Other Radio Rarities Jasmine CD 2549

Note: Jeff Barnhart and Hal Smith have also recorded tributes to Fats Waller (listed below).

Jeff Barnhart

Reflections of Fats Lake LACD 308

The Joint Is Jumpin’ (with the Galvanized Jazz Band) GJB 11 018

Wallerin’ Around (including the rare Waller song “Every Sweetie”) Jazz Alive JACD 1023

Hal Smith

Hal Smith’s Rhythmakers featuring Rebecca Kilgore: Concentratin’ On Fats Jazzology JCD 299

Hal Smith is an Arkansas-based drummer and writer. He leads the El Dorado Jazz Band and the

Mortonia Seven and works with a variety of jazz and swing bands. Visit him online at

halsmithmusic.com

Jeff Barnhart is an internationally renowned pianist, vocalist, arranger, bandleader, recording artist, ASCAP composer, educator and entertainer. Visit him online atwww.jeffbarnhart.com. Email: Mysticrag@aol.com