Set forth below is the fifty-first “Texas Shout” column. The concluding installment of a two-part essay, it first appeared in the June 1994 issue of West Coast Rag, now known as The Syncopated Times.

Set forth below is the fifty-first “Texas Shout” column. The concluding installment of a two-part essay, it first appeared in the June 1994 issue of West Coast Rag, now known as The Syncopated Times.

The text has not been updated. As most of you know, I no longer write record reviews, having retired from jazz writing (except for liner note assignments) in early 1998.

In last month’s “Texas Shout,” I told you how I got into record reviewing and how my “This Month’s Records” review column operates. These comments lead into a broader question of how readers should use record reviews. The answer is that, if you are using the reviews as a guide to shopping (which is what they’re for), you should remember that, though they are supposed to represent informed opinions, they are hardly absolute.

I recently reviewed a CD by one of the biggest contemporary names in uptown-style New Orleans Dixieland. I loved the album and gave it top grades.

The editor of a well-known jazz club newsletter, a fine jazz writer and musician (whose preferences favor Chicago style), later reviewed the same album, disliking it so much that, in his review, he wondered if the music was properly classifiable as jazz. A third reviewer, for one of the largest independent Dixieland periodicals (who gives so many mixed and unfavorable reviews that I personally wonder if he really likes Dixieland very much) gave the album a generally negative rating but noted some positive elements about it.

All three of these reviews were of the same disc, by seasoned writers, yet they came out in three quite different places. How is the reader supposed to harmonize that situation?

You don’t. You recognize instead that there never has been a recording, and never will be one, that every reviewer likes. If I praise a record to the skies, one thing I can be sure of is that there are other reviewers out there who, if they are required to review the same record, will hate every note on it.

Thus, you look for a reviewer whose tastes mesh with yours in such a way that his/her reviews can be relied on as a guide for buying records. Usually such a reviewer will be someone whose tastes coincide with yours, but you may find that the opposite works as well.

To illustrate: Nancy and I, pursuing our hobby of watching movies, have learned that Julie Salamon of The Wall Street Journal and Janet Maslin of The New York Times are almost always in line with our views. If either of them really likes a film, we’ll put it on our list of movies to see, and we’re rarely disappointed.

However, a few years back, we subscribed to a periodical which had, among its movie reviewers, one who just loved obscure, slow-moving art films. We learned that if this reviewer went into orbit over a feature, we should avoid it at all costs because we’d be bored out of our minds.

Similarly, one of our area’s newspapers, a while ago, had two movie reviewers whose tastes were reverse barometers to ours. If they recommended a film, we wouldn’t care for it, and if they disliked it, we’d often enjoy it.

For that reason, there’s no point in getting all bent out of shape if you read a record review that pans an album you enjoy. First of all, if you aren’t going to use the review as a basis for your own shopping, the review isn’t written for you anyway. Second, there are probably other reviews out there of the album, some pro and some con, that you aren’t going to run across, so what difference does it make if you happened to read this one and not one of the others? Just turn the page and concentrate on the next article.

There are those who have great difficulty accepting the fact that one of their favorite artists or recordings has received a negative evaluation in print. Such folks are quick to assume that the reviewer is biased, or has some hidden agenda or axe to grind.

I’ve received letters, some being remarkably abusive in tone, accusing me of all sorts of malevolences regarding my record reviews. One reader will tell me that I’m biased in favor of something, while another will come along to say that I’m biased against it. Someone else imagines that I’m using reviews to surreptitiously promote my own gigs by tearing down performances by other, supposedly competitive, artists.

This latter accusation reflects a significant misunderstanding regarding the impact of Dixieland record reviews these days. Such reviews appear in small-circulation periodicals and have virtually no economic impact on the artist or the record.

Most people who buy a Dixielander’s or a ragtimer’s records do so at in-person performances, wanting a souvenir of the occasion and not knowing or caring what some reviewer may have said about the album. Similarly, festival producers usually hire musicians as the result of seeing live shows, or hearing audition records and making up their own minds apart from published reviews.

Unless there are extraordinary circumstances in the picture, a rave review in WCR, The Mississippi Rag or a large Dixieland club periodical, one written by a well-known and respected reviewer, might produce a one-time blip of ten to twenty orders for the recording. So much for the “economic power” of record reviewers.

With respect to bias, such claims are, of course, always justified, but not usually in the sense that the irate fans think. Naturally I’m biased, in the sense that I have certain musical likes and dislikes. So do all other record reviewers, and so do all of you.

The better reviewers, however, understand what their preferences are and try to discount for them in some way so as not to be unfair to the artist. For example, some reviewers won’t write unfavorable reviews.

While I respect the reasoning behind such a policy, and while I personally dislike writing unfavorable reviews, I think that failure to deal candidly with weaker elements of the recordings does not properly service the needs of the record-buying public. If all the records are good ones, how do readers learn how to discriminate between Dixieland that is routine, average, superior and outstanding?

In my own case, I try to figure out what the artist is trying to do on his/her own terms, and judge as best I can whether the effort was successful regardless of whether I personally prefer the approach being taken. I’ll sometimes also comment on whether I think the objectives are worthwhile, but try to do so in a way that the reader will have enough information to disagree with me and buy the record anyway if his/her inclinations don’t square with mine.

Thus, I can think of a few instances in which I’ve given top grades to recordings which I knew I would never get off the shelf again. Typically, these are in jazz styles that seldom make it to the top of my listening-for-pleasure list, such as swing tinged with early bop.

In any event, most record reviewers I’ve read, whatever their deficiencies, are sincerely trying to give each recording their best, most honest appraisal. In fact, if any reviewer truly displays a hidden agenda that causes reviews to be slanted a certain way without regard to the music, the Dixieland/ragtime community usually sniffs out such problems in short order and the reviewer over time receives fewer review copies.

Readers who have trouble accepting the points just made sometimes wind up taking time and energy to write letters like this one, which came in not too long ago:

“Dear Mr. Wyndham:

I read with considerable disgust your snide review of [albums by Artist X]. I’ve followed Dixieland and ragtime music (especially the festival circuit) for many years, and purchased several of [X’s recordings]. I found them to be not only highly entertaining, but [X] is one of the best technicians I have heard in years, and is consistently inventive and musical in his arranging. Your assertion that [the letter quotes the unfavorable portion of my review] is insulting and in fact smacks of some professional jealousy. …

Mr. Wyndham, lest you think I’m totally biased in MY opinions, I have also purchased your tapes in the past, and although I’ve found them interesting in their historical content, the technical peaks you reach in your vocals and piano playing do not even approach the lows on [X’s recordings]. In other words, haul the log out of your own eye, or off your own piano keyboard, before attempting to pick the splinter off of other’s.

Very truly yours,”

Speaking of letters, another reader (whom I’ll call Y), who also disagreed with my assessment of X’s recordings, made the following provocative comments in his epistle:

“To validate my expenditure for [X’s recordings], I played them at a recent party, and they passed the shoulder-bobbing, ear-pleasing and foot-patting test with flying colors. This may not be as sophisticated and cerebral as Tex’s system, but it sure did make everyone feel good.

One doesn’t have to be a great chef to know when food tastes good.

Maybe reviewers shouldn’t be musicians or have any talent at all …”

Y makes some points here that are worth discussing. Let’s start with Y’s query as to whether or not there is any advantage in having reviews written by musicians.

On the surface, it would seem that a review written by a musician ought to be more worthy of the reader’s attention than otherwise. However, in the last analysis, I side with Y.

Perhaps a musician can add certain bits of color to the text that will make the review more interesting. I play along with every record I review before putting on the earphones for the second and more important review listen. I learn things about the recording by doing so that might not be apparent to a non-musician; sometimes that information finds its way into a review.

Similarly, a musician/reviewer, at least if he/she has been around for a while and an active part of the scene, may well have gotten to know some or all of the musicians on the record. While this situation can create awkward situations for those who are reluctant to criticize their friends, it does allow for the possibility that some backstage anecdotes might fit into the review, enhancing its general appeal.

However, the bottom line in any review is the quality of the judgment and how clearly that judgment is conveyed in writing. Musicians have no corner on either. Being a musician doesn’t mean that you can write well. Further, as we all know from some of the execrable bands we’ve seen from time to time, it also doesn’t mean that you have good taste.

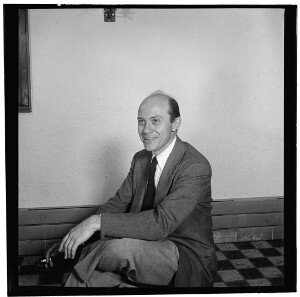

My all-time favorite jazz record reviewer, now retired I believe, is John S. Wilson, who wrote for, among other publications, The New York Times. If Wilson was able to play music, he never mentioned that fact in any of his writing that I can recall.

My all-time favorite jazz record reviewer, now retired I believe, is John S. Wilson, who wrote for, among other publications, The New York Times. If Wilson was able to play music, he never mentioned that fact in any of his writing that I can recall.

Nevertheless, Wilson had a broad and deep knowledge of our music, impeccable taste, and the ability to set down his thoughts in unmistakably clear prose. As Y puts it, “One doesn’t have to be a great chef to know when food tastes good.”

With respect to Y’s shoulder-bobbing test at his party, Y is certainly on the right track. The ultimate test of any recording, or other artistic performance, is whether it strikes an emotional response in its audience.

If you like a record, painting, movie, etc., it makes no difference what anyone else says about it — you’ll get your money’s worth out of it. However, I would respectfully suggest that Y’s criterion is really not sufficient for a prospective buyer of jazz records, unless one has unlimited funds.

Y does not tell us who came to his party. Perhaps all the guests were experienced jazz fans who sat down and quietly listened to the recordings. In that case, we would certainly have to give some weight to their reaction.

I think it more likely, though, that the recordings were played as background for a general gathering of Y’s friends, some of whom knew something about jazz and ragtime (but many didn’t). Most of them were probably chatting to each other, munching, drinking or engaging principally in other activities while the recordings were being played.

In that case, I think you’ll find that virtually any recording of pre-rock American non-classical, non-ethnic music – such as marches, twenties pops, banjo solos, blues, Dixieland, swing, polkas, thirties dance ballads, country music, etc. – will, even if not performed with much depth, get guests at a general party to tap their feet and bob their heads. Most such music, at least on the surface, when played with rhythmic cohesion, has a sufficiently outgoing quality that it will brighten a party, even though it might not stand up on a close listen by aficionados thereof.

Put another way, being able to get a general and inattentive audience in a better mood is virtually a rock-bottom minimum for a ragtime or Dixieland record. Except for the few I own where the rhythm section is obviously out of synch, just about any one of the thousands of recordings on my shelves, including some really bad records that I wish I’d never bought, will accomplish that purpose.

Indeed, that is one of the functions of the elevator music typically piped through office buildings. It puts everyone in a better mood although no one claims that it will survive critical listening.

Indeed, that is one of the functions of the elevator music typically piped through office buildings. It puts everyone in a better mood although no one claims that it will survive critical listening.

Thus, I don’t believe that you can truly “validate” your expenditure for a recording by playing it as background at your next cocktail party for your non-jazz-loving friends and observing whether any of them tap their feet. You’ll be buying everything that comes on the market if that, and that alone, is your standard.

Why go through this argument? Certainly not to disparage Y, who makes some good points and who commendably took pen in hand to defend a favorite musician.

However, I often hear variations of Y’s basic claim – that, if I can tap my feet or snap my fingers to the music, if it conveys an upbeat spirit, then it is worthwhile. This is a seductive position, but I think it puts its values on the wrong things.

Except in very special circumstances, if a ragtime pianist or Dixieland band has such poor rhythmic coordination that listeners don’t tap their feet, bob heads and be of a sunnier disposition, then it isn’t even out of the starting gate. It doesn’t deserve to be on record at all. If we value our music as an art form, we need to seek out artists who not only give us the basic minimum, but who have something new and worthwhile to say in the bargain.

Anyone can produce yet another recording that’s just like dozens of others in our collection. Given that none of us can afford to buy everything that’s out there, and that we wouldn’t have time to listen to all of it anyway, we should be trying to invest our recording budget in those sounds that go the farthest beyond the basics.

It is in this area that a record reviewer whose tastes coincide with yours can help. Reviews can sort through the plethora of available recordings, leading you to ones that will not only facilitate the action at your party but also provide more lasting rewards when you’re listening by yourself for the umpteenth time.

Further, if the reviewer is a good enough writer, he/she should be able to heighten your own awareness of fine points of the music that have hitherto escaped your attention. In that case, you will get even more satisfaction from both your purchases and attendance at live concerts.

One could ask why have record reviews at all anymore, given that they have the minuscule economic impact discussed above. It’s a good question, one I mentioned in my previous “Texas Shout” columns on record reviewing (September and October 1990).

Let’s not revisit that one today, though. Enough’s enough.

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

The full run of “Texas Shout” has been collected into a lavishly illustrated trade paperback entitled Texas Shout: How Dixieland Jazz Works. This book is available @ $20.00 plus $2.95 shipping from Tex Wyndham, On request, Tex will autograph the book and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Tex Wyndham’s 3 CD Guide to Dixieland with music and commentary is available for $20 plus $2.95 shipping. The separate CD, A History of Ragtime: Tex Wyndham Live At Santa Rosa, is available for $13.00 plus $2.00 shipping. On request, Tex will autograph the inner sleeve and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Send payment to Tex Wyndham, P.O. Box 831, Mendenhall, PA 19357, Phone (610) 388-6330.

Note: All links, pictures, videos or graphics accompanying the Shouts were added at the discretion of the Syncopated Times editorial staff. They did not accompany the original columns and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Tex Wyndham.

From roughly 1970-2010, Tex Wyndham was: (1) one of the best-known revivalist Dixieland jazz musicians in the US, as cornetist, pianist and bandleader, (2) one of the best-known ragtime pianists in the US, and (3) one of the most respected critics in the US of Dixieland jazz, ragtime, and related music. He is the only person about whom all three of those statements can be made.