The researchers Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff have made a monumental contribution to scholarship on the history of American popular music. In three large, thoroughly documented, lavishly illustrated volumes, they have produced a rich narrative illuminating the broad streams of African American music and entertainment that developed into jazz and blues in the early twentieth century.

The researchers Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff have made a monumental contribution to scholarship on the history of American popular music. In three large, thoroughly documented, lavishly illustrated volumes, they have produced a rich narrative illuminating the broad streams of African American music and entertainment that developed into jazz and blues in the early twentieth century.

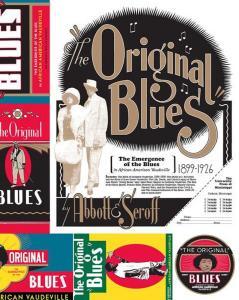

The authors used African American newspapers as their chief source, exhaustively mining publications like the Chicago Defender and the Indianapolis Freeman, which for years functioned as a sort of mobile messaging service for performers on the road. The culminating volume of the trilogy, The Original Blues: The Emergence of the Blues in African American Vaudeville, confirms the scope of their achievement. Focusing on the 1910s and early 1920s, the book puts the lie to received myths about the origin of the blues. It offers a more compelling story, with enough context and detail to advance how we understand both the birth of the blues and the gestation period that preceded it.

In 2002, Abbott, a curator at the Hogan Jazz Archive at Tulane University in New Orleans, and his colleague Seroff published Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889-1895. This book is structured as an annotated press diary with more than a thousand entries, chronicling the careers of a wide range of performers, from the Fisk Jubilee Singers to circus sideshows, brass bands, traveling minstrel troupes, and operatic divas such as Matilda Sissieretta Jones. Ragged but Right: Black Traveling Shows, ‘Coon Songs,’ and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz (2007) depicts the emergence of ragtime and “coon songs” in the period when the Supreme Court’s 1896 Plessy decision upheld segregation and Jim Crow rose in the south. An underlying theme of both volumes concerns African American music’s bruising encounters and negotiations with the white world and the American cultural marketplace.

The Original Blues picks up the thread at the turn of the twentieth century when the vaudeville stage was beginning to erode the dominance of minstrelsy among the styles of African American entertainment. In the south, a segregated black theater circuit was built, eventually crystallizing into the Theater Owners Booking Association (TOBA) in 1921. The “coon songs,” as their demeaning name suggests, represented the torturous paths black creativity had to weave in the white-dominated cultural landscape. Yet southern black vaudeville, Abbott and Seroff argue, gave its performers and audiences a sphere in which they could interact outside the mediation of white cultural gatekeepers, “out of sight.” This space nurtured bold forms of artistic expression, including the forthright musical idiom identified, starting around 1909, as “the blues.”

To illustrate the diffusion of the blues phenomenon in the pivotal decade of the 1910s, Abbott and Seroff delve into the story of Butler “String Beans” May, the first African American star to emerge from southern vaudeville and succeed up north. By 1911, only two years into his career, his bawdy comedy, piano playing, and dynamic singing and dancing had made him the top draw on the “colored small time.” He proceeded to delight audiences and attract big crowds in Chicago, the midwest, Philadelphia, and New York.

Northern critics, newly exposed to an authentically southern black style of bravado and double-entendre humor, reacted derisively, but by 1916 one dubious critic admitted that String Beans “will be readily conceded to be the blues master piano player of the world.” May died in 1917 and had been almost completely forgotten until the publication of The Original Blues. He neither recorded nor copyrighted his songs, but he directly influenced contemporaries such as Jelly Roll Morton, the vaudeville duo Butterbeans and Susie, and “Mama String Bean,” Ethel Waters.

A lengthy chapter of the book is devoted to female vaudevillians of the 1910s, including Gertrude “Ma” Rainey and Bessie Smith along with some less well known today. They were all comediennes and variety performers who sang in the evolving ragtime-cum-blues style. At the start of the decade, reviewers and promoters often tagged these women “coon shouters,” but after 1915 or so that term was replaced by the new honorific “blues queens.”

The book’s final chapter covers the 1920s, when the blues made its entrance into mainstream US culture. The 1920 hit recording of “Crazy Blues,” sung by Mamie Smith, revealed the existence of a commercial market for authentic black performance on gramophone and ushered in the era of “race records.” The sound of “Crazy Blues” and the structure of Perry Bradford‘s composition owe far more to Tin Pan Alley than to the Mississippi Delta, but Smith’s delivery smuggles in a revelatory blues sensibility.

For the next couple of years, this curious Harlem variant on the blues was prevalent on record, represented by singers such as Ethel Waters and Alberta Hunter whose stage experience was mostly in the north. Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith began recording in 1923. Bessie, recording for the Columbia label, scored hits with vaudevillian blues tunes such as “Downhearted Blues” and “T’ain’t Nobody’s Biz-ness If I Do,” and swiftly became the genre’s biggest star both on disc and on the TOBA circuit. Her moment at the summit of African American entertainment, however, was a brief one.

The same can be said of the male country blues artists of the south, many of whom recorded later in the ’twenties. They and their predominant instrument, the guitar, had been almost entirely absent from the vaudeville stage. They did much of their playing in the streets and were perceived, rightly or wrongly, as indigent. Their opportunities to record were largely cut short by the Great Depression, but they succeeded in distilling and disseminating the blues style as it had developed on southern stages.

Whereas most written blues histories essentially start with the rural blues guitarists, Abbott and Seroff devote only a few pages to them. However, the authors persuasively posit a direct link from the southern vaudeville piano blues pioneered by String Beans to the country guitar blues of artists like Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lonnie Johnson, and Charley Patton. The common element, as Abbott and Seroff see it, is that both groups of artists honed their craft performing for insular black audiences. Country blues did not come into existence sui generis, nor did it derive from purely rural or “folk” origins. It was a multifaceted transmission from the vaudevillians, who were themselves synthesizing and updating cultural traditions dating back decades. The masterful work of Abbott and Seroff has exposed these linkages in all their complexity.

The Original Blues: The Emergence of the Blues in African American Vaudeville By Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff. University Press of Mississippi (2017), 480 pages; Cloth $85.00; Paper $40.00 ISBN: 9781496823267 (www.upress.state.ms.us)

Roger Kimmel Smith is a freelance wordsmith (www.smithmeaword.com) based in Ithaca, New York. He’s written many musician profiles for Contemporary Black Biography. His all-20s/30s program “Crazy Words, Crazy Tune” airs Friday Afternoons (12-2pm) on WRFI Community Radio (www.wrfi.org).