Of all of the successful big band leaders of the swing era, Jimmie Lunceford had one of the most unusual beginnings. While most leaders were initially star sidemen in other orchestras, learning the trade and eventually forming their own groups, Lunceford was never a sideman or a featured soloist, singer, or arranger-composer. In fact, he was a physical education and language teacher. The band that he led in the 1930s and ’40s was in some ways as unusual as his beginnings. While his group was a top-notch swing orchestra, his soloists were secondary in importance to the arrangements, and the main emphasis was on presentation, showmanship, flawless musicianship, and putting on an entertaining show. While Lunceford’s orchestra was at times compared to Duke Ellington and Count Basie, in reality his approach was closer to that of a more jazz-oriented Paul Whiteman.

James Felton Lunceford was born in Fulton, Mississippi on June 6, 1902. He grew up in Oklahoma City and Denver, studying music in Denver with Wilberforce Whiteman, the father of Paul Whiteman. Lunceford had already played a little bit of guitar and banjo by that time, and he soon expanded to violin, trombone, piano, flute, and all of the saxophones, settling on the alto-sax. Doubling on alto-sax and violin, Lunceford made his recording debut in 1920 with violinist George Morrison’s Jazz Orchestra, an 11-piece group that included future bandleader Andy Kirk on alto and bass sax. While they recorded seven selections, unfortunately only one song, “I Know Why,” was ever released and Lunceford is only heard (and barely) as part of the ensemble.

In 1922 he moved to Tennessee where he attended Fisk University in Nashville, earning a degree in sociology while also studying music and playing alto sax in the student jazz band. He spent a period in New York taking postgraduate classes, working briefly on alto and piano with Wilbur Sweatman and Elmer Snowden. In 1927 Lunceford got a job at Manassas High School in Memphis teaching athletics, English, Spanish, and music. Little known at the time was that he was possibly the first educator to ever teach jazz in school.

In October 1927, the school teacher decided to form a jazz band comprised of some of his best students. As The Chickasaw Syncopators, they recorded two numbers on December 13, 1927 (“Chickasaw Stomp” and “Memphis Rag”), already sounding surprisingly skilled. Two of the young musicians, Moses Allen (on tuba and preaching throughout “Chicakaw Stomp”) and drummer Jimmy Crawford would be longtime members of the Lunceford Orchestra. The leader, while not playing any instruments on this session, was in charge of forming and developing his band’s sound and one can hear hints of what was to come.

The Chickasaw Syncopators worked locally, had some regional success, and in 1929 became professional musicians. While Lunceford stopped teaching in schools, he remained a teacher to his sidemen throughout his life. A bit of a taskmaster and a perfectionist, he not only expected impeccable musicianship but he also wanted his sidemen to blend together and create a group sound with catchy arrangements rather than relying on hot soloists. He believed in putting together and performing a fast-moving show filled with variety, comedy, costume changes, choreography, vocals (many of his star sidemen sang), and dancing in addition to colorful solos. His orchestra rehearsed constantly and within a few years was achieving his goal.

The Chickasaw Syncopators recorded two numbers in 1930 while still in Memphis (“Sweet Rhythm” and another vehicle for Moses Allen’s preaching, “In Dat Mornin’”). The personnel by then included pianist Ed Wilcox who became the band’s first important arranger, altoist Willie Smith, and trombonist Henry Wells. Soon renamed the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra, the band traveled, struggled, and developed. The Depression slowed down their progress but they persevered and during 1933-34 their fortunes changed. Lunceford and his musicians settled in New York and on May 15, 1933 had their first recording session in three years, resulting in “Flaming Reeds And Screaming Brass” and “While Love Lasts.” While those recordings remained unreleased for decades, the band’s personnel was now in place with Tommy Stevenson playing high notes on the trumpet, Henry Wells playing trombone and singing, and the saxophone section including tenor-saxophonist Joe Thomas. Soon afterwards, Sy Oliver joined the band, making an impact not only as a fine trumpeter and a personable singer but as an innovative arranger whose utilization of a two-beat rhythm helped make the Lunceford band sound even more individual.

In 1934 the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra became a regular attraction at the Cotton Club (filling in for Cab Calloway), recorded two sessions for Victor that were released (including “White Heat,” their theme song “Jazznocracy,” and “Swingin’ Uptown”), and began a longtime association with the Decca label. The band was on its way to the top, playing their brand of swing a year before Benny Goodman’s great success launched the Swing Era.

While there would be a few additions and personnel changes during the next five years (Paul Webster replaced Tommy Stevenson as the band’s high note trumpeter, the very valuable trombonist-guitarist-arranger Eddie Durham joined, trombonist Trummy Young became a band member in 1937, and altoist Dan Grissom was used as the band’s ballad singer), the group enjoyed stability and success. Jimmie Lunceford regarded the orchestra as very much of a family band.

“Rhythm Is Our Business” (with Willie Smith on the vocal) was the first of the Lunceford hits. It was followed by such popular numbers as “Sleepy Time Gal” (which has a remarkable arrangement by Ed Wilcox that shows off the brilliance of the saxophone section), “Four Or Five Times,” Sy Oliver’s reworking of “Swanee River,” “My Blue Heaven,” “Organ Grinder’s Swing,” “Harlem Shout,” “For Dancers Only,” Trummy Young’s feature on “Margie,” “By The River Sainte Marie,” “Cheatin’ On Me,” “Well All Right Then,” and “’Tain’t What You Do (It’s The Way That Cha Do It).” 1935’s “Hittin’ The Bottle” is also noteworthy for it has Eddie Durham playing a pioneering electric guitar solo.

The shows put on by the Jimmie Lunceford became quite legendary. Many of the musicians (including the key soloists Sy Oliver, Trummy Young, Willie Smith, and Joe Thomas) were quite capable of taking jazz-oriented vocals, both as soloists and as a type of glee club. The arrangements of Oliver and Edwin Wilcox were joined by charts written by Smith, trumpeter Eddie Tompkins and such talents from outside the band as Will Hudson, Jesse Stone and Billy Moore. The band’s choreography, their showmanship, and their clean cut yet hip image were also major factors in the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra finding its place in the music world. They were so popular that in 1937 they had a successful tour of Europe.

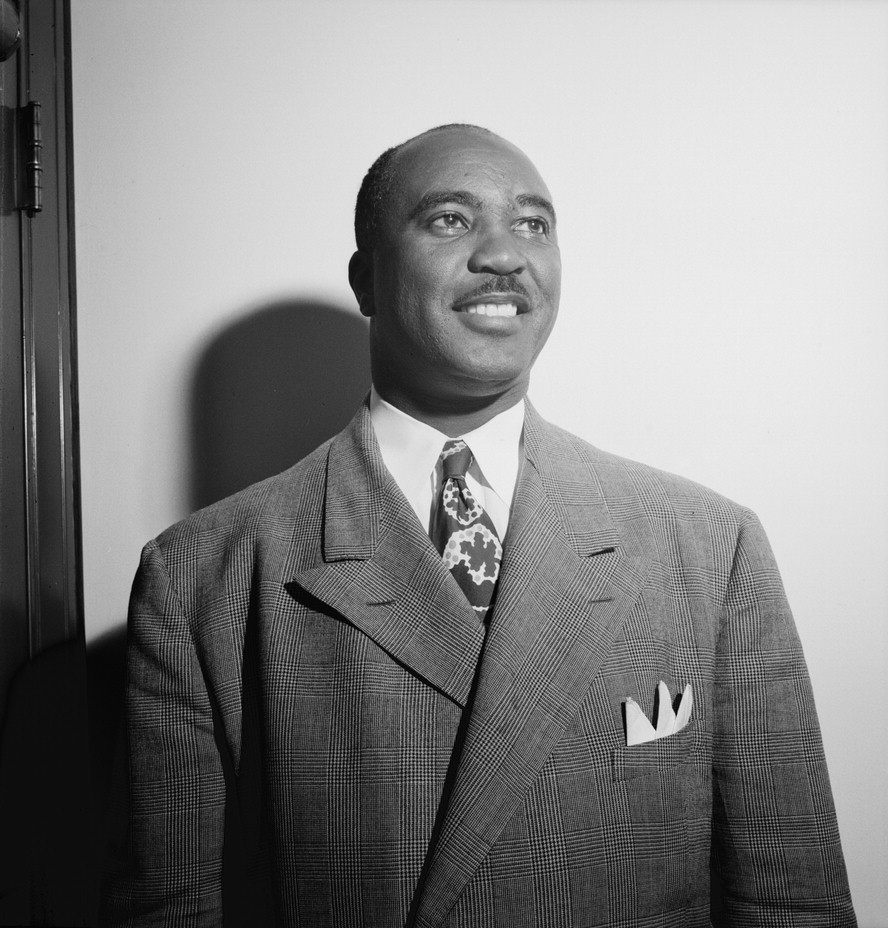

There are few films of the band, in fact only two that I know of. They appeared in the 1941 movie Blues In The Night playing the title cut but best is a wonderful 10-minute short from 1936 that is simply titled Jimmie Lunceford and His Dance Orchestra. The fast-moving film is highlighted by “Jazznocracy,” an uptempo “Rhythm Is Our Business,” and a hot version of “Nagasaki” that at one point has two of the saxophonists dancing while holding their horns. All of the key soloists have brief spots, the choreography shows what Glenn Miller learned from the band, and this film gives one a good idea of what it must have been like to see the Lunceford band in person. The leader, who beams throughout while conducting his orchestra, looks proud and happy.

While he was a skilled and versatile musician, Jimmie Lunceford rarely played with his orchestra. He occasionally filled in on alto but his only known solo was a feature on “Liza” on flute that was saved from a radio appearance in the mid-1940s. He only wrote a few of the band’s early arrangements and sometimes looked like a figurehead who conducted the orchestra. But in reality he oversaw the contributions of his sidemen and arrangers and it was his vision that resulted in the orchestra having its own sound and those colorful shows.

In the summer of 1939, Sy Oliver was lured away with a lucrative offer from Tommy Dorsey. His successor, trumpeter Gerald Wilson, proved to be a perfect replacement for a few years, particularly when it was discovered that he was also a fine arranger as displayed on his “Hi Spook” and “Yard Dog Mazurka.” The Lunceford Orchestra was signed to the Vocalion/Okeh label during 1939-40 (continuing with such numbers as “Uptown Blues,” “Lunceford Special,” and “What’s Your Story, Morning Glory”) before returning to Decca where, among their recordings, were a two-part “Blues In The Night” (a standard that they introduced) and “Strictly Instrumental.” With Snooky Young as their new lead trumpeter, the band’s potential seemed endless and many would have thought that they had many prosperous years ahead of them.

However there was one major problem beyond World War II, when gas and rubber rationing made traveling difficult. While Jimmie Lunceford was making very good money from his band’s success, he was notorious in paying low salaries to his sidemen, feeling that being part of the musical family was enough. One by one starting in 1942, many of his star sidemen departed and by 1944 Willie Smith (who joined Harry James), Trummy Young, Gerald Wilson, and Jimmy Crawford were long gone. While the hits stopped, Lunceford carried on and his band remained popular and still featured top-notch musicianship. Among his sidemen during 1944-47 were at various times tenor-saxophonist Benny Waters, trumpeter Freddie Webster, trombonist Fernando Arbello, and Omer Simeon on clarinet and alto. The influence of the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra could be felt on many other bands including most notably Glenn Miller (particularly in the choreography) and Stan Kenton who also featured high note trumpeters and thick-toned tenor-saxophonists.

Lunceford’s Decca contract ended in 1945 but his band continued recording for the Majestic label. While still working steadily and remaining a constant on the radio, the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra was largely coasting during this final period, playing their older hits and covering material made famous by others. The band largely ignored bebop and rhythm & blues while struggling to keep its identity fresh. There were some hopeful signs and the Lunceford name was still considered magical. The leader had plans for another European tour and he was hoping to hire back some of his earlier sidemen with higher salaries than they had formerly been paid but he had not charted out a new direction yet.

On July 12, 1947, while on tour in Seaside, Oregon, Jimmie Lunceford died of a heart attack after eating tainted food. Because he was just 45 years old, there were rumors that he was poisoned by the owner of a restaurant who did not want to serve African-Americans. But that might be false because he had been suffering from pains in his leg and had high blood pressure along with the constant pressure of leading his big band in the post-swing era.

Joe Thomas and Edwin Wilcox kept the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra together into 1949, even making some new recordings, but it did not last. Without their leader, the band ran out of gas. Its time had passed.

Since 1975 Scott Yanow has been a regular reviewer of albums in many jazz styles. He has written for many jazz and arts magazines, including JazzTimes, Jazziz, Down Beat, Cadence, CODA, and the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, and was the jazz editor for Record Review. He has written an in-depth biography on Dizzy Gillespie for AllMusic.com. He has authored 11 books on jazz, over 900 liner notes for CDs and over 20,000 reviews of jazz recordings.

Yanow was a contributor to and co-editor of the third edition of the All Music Guide to Jazz. He continues to write for Downbeat, Jazziz, the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, the Jazz Rag, the New York City Jazz Record and other publications.