Set forth below is the sixty-eighth “Texas Shout” column. The concluding installment of a two-part essay,(part 1,) it first appeared in the December 1995 issue of TAR. The text has not been updated.

Set forth below is the sixty-eighth “Texas Shout” column. The concluding installment of a two-part essay,(part 1,) it first appeared in the December 1995 issue of TAR. The text has not been updated.

Having disposed, to your satisfaction I hope, of a couple of the less prevalent arguments against the word “Dixieland,” I now want to address the most poorly thought out, dumbest, most baseless objection to the word, and the one that is always tossed out first by people who don’t like the term. They will claim that “Dixieland” is indelibly associated in the public’s mind with musicians who wear straw hats, striped blazers, striped vests and/or similar so-called period attire and who play shallow music.

This statement is made as if it is incontrovertible truth and as if it means something significant. It is supposed to end the discussion. The time has come for true supporters of our music to confront and destroy this deep-seated myth face to face.

So many questions are raised by the striped-blazer assertion that it’s hard to know where to start asking them. For example, in my earlier columns I wondered how a style of music could in any way be defined by what the musicians are wearing when they play it. More to the point, just exactly what is supposed to be wrong with striped blazers anyway?

I’ll be willing to bet that nearly every festival or club that presents Dixieland, whether it favors the term or not, has at one time or another advertised one of its events with a drawing depicting a musician in a straw hat, striped blazer or striped vest. This practice reflects the common sense viewpoint that, if there is an image that suggests a wholesome good time to potential attendees, why not make use of it?

For that matter, I know of no festival or society concentrating on pre-swing jazz that refuses to hire bands which wear straw hats, striped vests or striped blazers. Nor am I aware of one that prohibits musicians or members of its strutters’ groups from wearing such attire to its functions.

Come to think of it, at this writing there are several highly regarded, well-traveled bands on the circuit that wear blazers with some regularity, though usually solid-color ones. Should we conclude that blazers are really O.K. after all as long as they aren’t striped? Precisely what is this magical quality of stripes which, when they are applied to a jazzman/woman’s blazer or vest, cause musical notes to curdle upon emerging from the instrument?

In any event, musicians have to wear something on the bandstand. Striped blazers, in my book, look a lot better than the costume considered de rigeur in certain circles of the British trad style, where the artists apparently are trying to create the impression that they have just rushed onstage after having spent the last eight hours underneath the car changing the crankcase oil.

I love British trad along with the other six Dixieland styles. However, I much dislike the custom adopted by those British trad bands who make a special point of looking like ragamuffins, even when playing in expensive concert halls.

I can swallow my bile regarding the disrespect that is thereby shown to the music and also to the audience (which has usually taken the trouble to dress more suitably for the occasion). However, I can’t forgive the fact that these bands are doing nothing to attract outsiders to our music.

Unless they’re hoping to convert grunge rockers to Dixieland, they ought to know that few members of the general public are going to go out of their way to patronize scruffy-looking musicians. Indeed, quite a few potential Dixielanders may be so turned off by an out-at-elbows appearance that they won’t take time to appreciate the music. Dixieland isn’t healthy enough to tolerate such a cavalier attitude by its practitioners.

Next questions: Just exactly how did Dixieland get this striped blazer image? When did it happen? Which bands and musicians, specifically, were responsible for it? How many of the general public really remember those artists? Why can’t the image be erased over time by the good bands that have come along in the interim?

Ask these questions the next time some anti-“Dixieland” type incants the straw hat/striped blazer dogma. You won’t get any well-focused answers. These folks just assert that “Dixieland” equals striped blazers equals shallow music as if everyone with any knowledge of the subject ought to agree.

I’ve seen it written that the striped blazer connection was made in the fifties, though no specific names were accused. Well, I was collecting Dixieland in the fifties and sixties. I don’t recall that there were hordes of schlock bands destroying Dixieland jazz at that time.

I do remember, though, that there was something of a commercial resurgence of Dixieland in the fifties, lasting about ten years before jazz started to fade, like other pre-rock music, in the glare of Beatlemania. A key band in that revival was The Firehouse Five Plus Two, which regularly appeared in firemen’s uniforms.

However, the FH5 is (rightly) idolized in the current festival scene, so I guess it couldn’t have been one of the bands that ruined “Dixieland” with its costumes. Or are the anti-“Dixieland” folks saying that if everyone had only worn firemen’s uniforms instead of striped blazers, they wouldn’t have a problem with the word?

I also remember that several record labels, in the early days of 12″ LPs, promoted their Dixieland recordings with cover drawings or photographs of the musicians in costumes. Capitol, for example, did so with regularity on albums by, among others, Pete Daily, Bob Crosby, Ray Bauduc, Sharkey Bonano, Red Nichols, Jack Teagarden and other fondly recalled jazzmen.

Are these great players the villains who are supposed to have prostituted our music? If so, why do used copies of those LPs, the ones which haven’t been reissued on CD, draw such high prices on the collectors’ market? Besides, what influence do performers have over the way record companies promote albums?

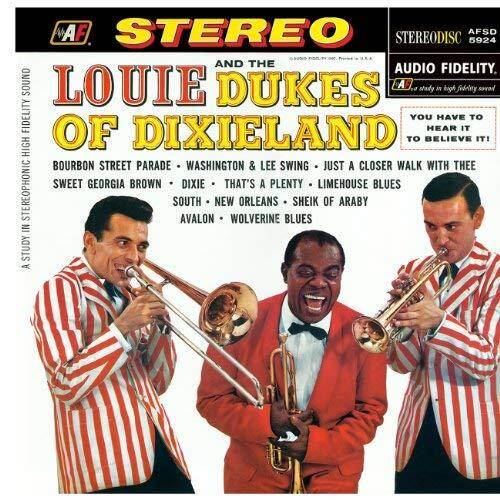

In the early days of high fidelity, the Audio Fidelity label released an immensely successful series of LPs by The Dukes Of Dixieland, many of which had special themes and came in jackets showing the band in costumes consistent with the themes. Are these the cause of the striped blazer curse?

If so, how do the anti-“Dixieland” people deal with the fact that the band itself, the Assunto brothers edition of the Dukes, was one of the best Dixieland bands of its day, one that would mop up the floor with most of today’s Dixieland bands in head-to-head competition, one that created such lasting fame for itself that a version of the Dukes has stayed on the boards pretty much ever since?

If so, how do the anti-“Dixieland” people deal with the fact that the band itself, the Assunto brothers edition of the Dukes, was one of the best Dixieland bands of its day, one that would mop up the floor with most of today’s Dixieland bands in head-to-head competition, one that created such lasting fame for itself that a version of the Dukes has stayed on the boards pretty much ever since?

In fact, the popularity of the Dukes’ Audio Fidelity LPs raised the consciousness of a sizeable slice of the general public toward Dixieland. We’d be very lucky if a Dixieland band came along today that duplicated its success, no matter what kind of costumes it wore or how it was marketed.

By the early 1960s, a string of sing-a-long banjo clubs had sprung up across the country in chains with names like The Red Garter or Your Father’s Mustache. The mandatory uniform for the musicians was a striped vest. Were these night spots the culprits who trashed Dixieland?

The difficulty with that idea is that a fair number of today’s Dixielanders about my age spent some time working in those clubs, myself included. Every one of them I’ve talked to has positive memories of the experience.

Although the music played by the resident banjo bands was vintage pop, not Dixieland (I doubt that many people thought it was Dixieland), most of the venues did book legitimate Dixieland bands on weekend afternoons or slow nights. These establishments thereby provided lots of work for Dixielanders of their day and attracted respectable crowds to a scene where the audience was immersed in Dixieland-influenced music. Striped vests or not, all Dixielanders would be much better off if the banjo sing-a-long fad were to recur.

Does the stigma on “Dixieland” stem from pizza parlors? I doubt it. Before the 1960s-70s, when Dixieland took hold for some years in pizza and other fast-food emporia, there was already a faction abhorring the word.

I suppose we’ve all seen glib disparaging comments about a “pizza parlor image,” but frankly, what’s wrong with playing in a pizza restaurant? Has there ever been a Dixieland artist stupid enough to turn down a paying gig just because pizza was sold on the premises?

Nobody has any trouble with our music being played in bars. Why is there supposed to be something demeaning about playing it in a family situation where booze isn’t the main entree?

Besides, like the sing-a-long clubs, the pizza joints provided steady employment for Dixielanders for many years. Our community owes them a debt of gratitude.

In fact, in acknowledgment of the support these eateries gave our music, the owner of the Shakey’s chain was honored a few years back as the Sacramento Jazz Jubilee’s official emperor. Like it or not, it’s too bad for us that you don’t hear much Dixieland any more in pizza parlors.

I’ve tried and tried to get people to give me facts about the origin of this striped blazer slander, but without success. It is simply another piece of phony jazz lore, one of those things that just isn’t so about Dixieland that gets mindlessly repeated by people who ought to know better.

However, suppose it all were true? Let’s pretend that the word “Dixieland” really does mean shallow music played by silly bands wearing gaudy clothes in which the trombonist always works the slide with his foot and the trumpet player fingers his horn upside down? What if the impossible happened and some other word than “Dixieland,” say “traditional” or “classic,” were widely recognized by today’s general public to mean high-quality, uncommercial, deep, twenties-style jazz?

Sooner or later bands would come along that were 100%-schlock outfits trying to get a free ride on our pristine image by claiming to be playing “traditional” or “classic” jazz. Given that the public doesn’t always bestow its acclaim on those most worthy, some of those schlocky bands would become popular and start getting more bookings than the excellent more deserving bands. These shallow bands would thereby tarnish the hard-won image of “traditional” or “classic.”

What are we supposed to do then? Go through the same process? Decide that “traditional” or “classic” now means schlocky music and start down the long road of converting the public to some other word? Of course not. So lets’s make the most of “Dixieland,” the word we already have.

In the years since I wrote that first column about “Dixieland,” I’ve probed all of the reasons people have given me for disliking the term. None survives close analysis.

Not finding any other explanation for resisting “Dixieland” that satisfies me, I have concluded that the anti-“Dixieland” folks really, deep down inside, want to be part of an elite in-group that can congratulate itself on appreciating some music known by a term only they understand. Such an attitude is, of course, totally self-destructive in terms of the Dixieland community’s urgent need to recruit new supporters from outside our ranks.

However, Dixielanders regularly engage in much self-destructive conduct, e.g., lack of cooperation between geographically adjacent Dixieland clubs, pointless infighting among supporters of different Dixieland styles. I suppose one more instance of it won’t make much difference.

Therefore, if you have some compulsion to do so, you might as well keep on proclaiming that “Dixieland” is shallow trivial music, that you don’t play it or listen to it, and that you really are involved with jazz described by some other term that you need to explain to neophytes in the crowd. However, as far as I’m concerned, every time you mouth that litany, you’re loosening one more plug in Dixieland’s already fragile life-support system. Whether you know it or not, you’re part of the problem.

* * * * *

The following note was added to a February 2004 reprint of this column.

As an afterthought to this discussion, I can’t help noting that a segment of the older-style jazz community continues, against all common sense, to try to find new words for the music it likes instead of the ones everyone knows. The latest, as most steady TAR readers know, is “OKOM,” an acronym for “our kind of music.”

As best I can figure out from the times I’ve been confronted with the term, “OKOM” most often seems to be covering some general area of pre-bop music, mostly jazz styles. At any rate, I feel sure that OKOM does not include ethnic music, classical music, heavy metal rock, fusion, third stream and bop (and post-bop) jazz.

Does OKOM include swing? One might normally think so, but it is used frequently on the Dixieland internet chat line, so I guess it doesn’t.

OKOM is frequently referred to in this publication, which deals with events that commonly present country/western, blues, zydeco and ragtime. Does OKOM include those musics? If not, which ones are excluded?

If I say “Dixieland,” “swing,” “progressive,” “bop,” “ragtime” to jazz aficionados, at least 90% of them, whether or not they like the music being discussed, will have a reasonably precise idea of what I’m talking about. Can anyone give me a definition of “OKOM,” covering exactly the types of music included therein and excluded therefrom, that will be accepted and agreed to by as much as 75% of the people who are now tossing around this term so casually? I thought not.

In that case, what good is it? Why, when Dixieland, swing, ragtime and other musical forms from the 1900-1950 era are hanging on by their fingernails already, are we turning ourselves into pretzels to invent vague new terms to describe them instead of the labels everyone understands?

My best guess is that “OKOM” is yet another product of the self-destructive, elite, in-group mentality mentioned in the above reprint. That is, we can now say that “OKOM” has become another part of the problem.

Aren’t you being a bit hypocritical here, Tex, you ask, because you use the phrase “our music” with some frequency in your own writings, including the column reprinted above? Not guilty.

I use “our music” for stylistic reasons, to avoid repeating a word incessantly where the context has already made it crystal clear exactly which type of music I’m discussing. If, after you finished the above article, you failed to understand that I was talking about Dixieland jazz and nothing else, then I should have retired from jazz writing much sooner than I did.

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

The full run of “Texas Shout” has been collected into a lavishly illustrated trade paperback entitled Texas Shout: How Dixieland Jazz Works. This book is available @ $20.00 plus $2.95 shipping from Tex Wyndham, On request, Tex will autograph the book and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Tex Wyndham’s 3 CD Guide to Dixieland with music and commentary is available for $20 plus $2.95 shipping. The separate CD, A History of Ragtime: Tex Wyndham Live At Santa Rosa, is available for $13.00 plus $2.00 shipping. On request, Tex will autograph the inner sleeve and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Send payment to Tex Wyndham, P.O. Box 831, Mendenhall, PA 19357, Phone (610) 388-6330.

Note: All links, pictures, videos or graphics accompanying the Shouts were added at the discretion of the Syncopated Times editorial staff. They did not accompany the original columns and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Tex Wyndham.

From roughly 1970-2010, Tex Wyndham was: (1) one of the best-known revivalist Dixieland jazz musicians in the US, as cornetist, pianist and bandleader, (2) one of the best-known ragtime pianists in the US, and (3) one of the most respected critics in the US of Dixieland jazz, ragtime, and related music. He is the only person about whom all three of those statements can be made.