Set forth below is the seventy-second “Texas Shout” column. It first appeared in the May 1996 issue of TAR. Because the text has not been updated, perhaps I should remind you that the great Bob Helm has since passed to his reward.

Set forth below is the seventy-second “Texas Shout” column. It first appeared in the May 1996 issue of TAR. Because the text has not been updated, perhaps I should remind you that the great Bob Helm has since passed to his reward.

Is it possible for a recording to be so important that it is an essential purchase for a dedicated Dixieland/ragtimer even though it contains music that is of little merit artistically? Sure. I see examples turning up on the market all the time.

I don’t want to gratuitously trash something that’s in the stores right now. Thus, I’ll make my point with a hypothetical illustration.

The first known jazzman was cornetist Buddy Bolden, who led a band in New Orleans in 1895 that played music supposedly recognizable as jazz. Legend has it that Bolden’s sound was preserved on a cylinder.

If so, the recording probably no longer exists. Anyway, it has never appeared in the Dixieland community.

If Bolden’s cylinder were unearthed, it would be of inestimable importance to Dixieland research because we would be able to hear what jazz sounded like at a time close to its moment of birth. However, measured by normal standards of jazz criticism, the performance probably won’t be musically worthwhile. The odds are that what we’d hear, in terms of artistic merit, would be near the bottom of the jazz scale.

I recognize that some of Bolden’s contemporaries reported him to be a powerful player with a sweet tone, an artist who could touch his listeners’ emotions. Still, I can’t help but think that someone who was in at the very beginning of jazz is unlikely to have been able to foresee how the music would unfold – its depth, breadth and technical achievements – to such a degree that his own playing could bear scrutiny by today’s accepted criteria.

Since the dawn of the LP era, we have been fortunate enough to be presented with previously unheard renditions by some of the great names in our music. Alternative takes or rejected titles by artists like King Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton and Fats Waller have now been included in comprehensive collections of their 78s.

Almost all such performances recorded in the 1920s are the product of professional recording companies. Private individuals rarely possessed recording equipment in those years because it was so bulky and expensive.

As a result, the treasures that have been brought to light from the twenties provide not only useful additional perspective on the approaches of the artists involved, but also, in most cases, pleasing jazz. When the musicians appeared in a recording studio, they were likely to be as well rehearsed as was feasible, ready to perform at peak. Moreover, the studio ordinarily did its best to record everything with optimal acoustics, not knowing which takes would be accepted.

In many cases, the rejected versions are just as good acoustically as the accepted one. Sometimes the luck of the draw caused a certain performance to be issued vs. another. In just as many other cases, the flaw that led to rejection is a relatively minor part of an otherwise up-to-standard ride.

Another source of previously unheard vintage jazz is air checks from the twenties and thirties. Sometimes the radio studios themselves recorded their own broadcasts for later reuse. Sometimes private individuals preserved them on home recorders that, if too cumbersome to be transported to a gig, could at least be brought close to the radio speaker.

Live air checks are riskier than studio recordings in terms of quality because there is no opportunity for the musician to do the number again. However, they do share some of the safeguards against substandard music as do alternative or rejected takes.

First, the artist was also aware that he/she was performing for a broad audience and should have been trying to present his/her best side. Second, though air checks typically lack some of the resonance and overtones of a studio recording, they were produced by professional sound people who were trying to position the musicians most felicitously opposite the microphone.

After World War II, this situation changed. Recording machines were more portable, perhaps suitcase-size, and more accessible to private persons. As electronics invaded the recording industry, recorders became more compact and inexpensive.

From the sixties on, small tape units started appearing at jazz venues with increasing frequency. Today, everyone owns a hand-held recorder. Virtually every note a jazzman plays on a public gig, and even lots of private gigs, now winds up being recorded by someone. [See: Texas Shout #6 Hand-Held Live Tapes]

Many of the great Dixieland pioneers did not survive into the sixties. However, two of the seven Dixieland styles, West Coast revival and British trad, did not come along until the revival period. Their founders, players like Turk Murphy and Ken Colyer, lived into the eighties. Some of Murphy’s and Colyer’s contemporaries, e.g., Bob Helm and Chris Barber, are still going strong at this writing.

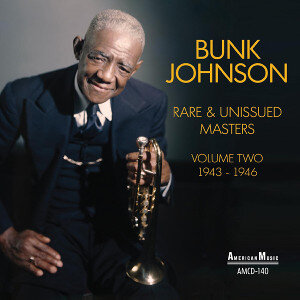

Further, while the uptown New Orleans style was around and being recorded in the twenties, it really got its prime initial momentum from Bunk Johnson’s first 78s in the early forties. Many of Johnson’s best sides were produced by jazz historians such as Bill Russell using bulky but portable equipment set up in private homes or neighborhood dance halls. These platters inaugurated a reasonably steady stream of uptown buffs who descended on New Orleans over the years to document whatever was happening jazzwise at neighborhood taverns or elsewhere in the Crescent City.

As a result of all of these developments, there exist today many private amateur recordings of great Dixieland names like Ken Colyer and Kid Thomas. They were typically casually recorded at gigs by someone who set up recording equipment to preserve the goings-on for his/her own personal pleasure.

Now that a number of these immortals are no longer alive, their amateur recordings are starting to find their way onto CD. We should be grateful therefor. The sides not only supplement the finite quantity of studio sessions which these players left behind, but also supply a basis for studying an artist’s approach to a tune that, perhaps, he/she never recorded commercially, or how his/her in-person show might have differed from what was selected for recording purposes.

These blessings are not without their down side. Such recordings do not have the quality safeguards listed above regarding fidelity or performance.

With regard to fidelity, casual microphone placement can and often does favor certain instruments at the expense of others, giving us a wrong idea of the way the band sounded in the room. Similarly, crowd noise can be obtrusive; if you’re hearing something preserved by a hand-held recorder at a table or seat out in the audience, casual conversation and other clatter will, in most cases, mask the subtleties in the music so that the featured artist’s special abilities do not come through.

With regard to performance quality, at a casual gig (as compared to a studio recording or air check) the artist is more likely to be at less than top form. He/she may be fatigued, be dealing with difficult acoustics or an inattentive audience, getting used to substitutes or unfamiliar sidemen, trying out new ideas at the end of the evening, etc. There are a million reasons why a casually made recording would capture something that is not representative of the artist and which would not be approved by him/her for public release.

A person who owns such material, and who is moved to put it on the market, may very well be blinded to such deficiencies. Such a producer could easily be one who idolizes the musician involved and who is incapable of recognizing that there is anything less than essential about his/her every note.

As a heavy collector of Dixieland, I have recently acquired quite a few CDs by some of my favorite players, all top names in the field, that are in this category. I’ve listened to genius defeated by out-of-tune pianos or coping with rowdy crowds or filtered through recording processes so lacking in presence that the jazz is harsh and utterly devoid of buoyancy.

On an absolute scale, the music on some of these albums can only be described as artistically terrible. Yet, I don’t regret buying them, even though I probably won’t re-listen often. I much admire the musicians thereon and appreciate the opportunity to get additional perspective on their work. I’m glad the discs are on the market.

When I read the liner notes thereon, I will occasionally find apologies for the fidelity. However, the producers (perhaps understandably) never even hint that the musicians might be operating at anything less than their usual standard. Similarly, I’ve encountered critical reviews of such recordings in which demerits of the specific album are brushed aside in waves of generalized eulogies for the artists involved.

These aspects of the situation bother me. Fewer and fewer Dixieland records are being issued at all these days. If this kind of casual session, aimed at collector/completists, is going to take a larger part of the market, then it is more likely to come into the hands of an unsophisticated listener, perhaps someone who is sampling our music – a prospective recruit to our cause.

What is such a person going to think when he/she struggles to dig fairly ordinary jazz out of an acoustical din while reading critical commentary praising it to the skies and liner notes asserting that it is a rare treasure that should be savored for its own sake? I doubt that we’ll find many such individuals electing to pursue Dixieland in depth or risking their dollars on more Dixieland CDs.

As a simple solution, I’d like to see two things happen. I recommend that both producers and reviewers (1) remain aware of the fact that the artist whose casual session is being issued gained his/her reputation not via this previously unheard date but through other, usually better, recordings and (2) do something to point a listener toward them.

CD producers: How’s about listing in your CD insert a few of the featured player’s in-print albums that reflect what the Dixieland community regards as his/her best output? A purchaser thereby (a) will have some feeling of where your album falls on the spectrum and (b) can be pointed in the right direction in the future.

Record reviewers: If you can’t bring yourself to give a negative rating to this type of CD, how’s about including in the text of your review something to orient your reader as to where the album fits into the overall body of the artist’s work?

Doing so will not result in discouraging sales to the principal intended market, the performer’s pre-sold disciples. They’ll want the record no matter what it sounds like.

However, it may well keep someone who has unwittingly become exposed to a very poor recording from deciding not to delve further into our music. As you know, in this era of rap and heavy metal, we need all the fresh blood we can get.

* * * * *

The following note was added to a previous reprint that ran in the June 2004 issue of The American Rag.

“Texas Shout” will terminate with the last reprint, scheduled for three issues from now. I guess it’s natural enough that, as the column winds down, I’ve been reflecting on some of the points I’ve made in it over the years.

One that comes to mind fairly often these days is the following quote, originally published in “Texas Shout” for the March 1994 issue of TAR (then called West Coast Rag): “My prediction is that, ten years from now, Dixieland festivals and societies will have done one of three things: (1) substantially changed emphasis with respect to the type of music they present, (2) substantially reduced the scope of their operations, or (3) folded.”

It gives me no pleasure to report what long-time TAR subscribers already realize, i.e., that my prediction came true almost to the day. Dixieland jazz is disappearing from the festival scene at such a rapid rate that it probably won’t be much longer before I’m going to be spending a lot more time at home with my recordings, books, sheet music and videos instead of traveling to perform at festivals.

I much enjoy playing Dixieland jazz and ragtime as well as entertaining people. Thus, during the 35-plus years I’ve spent on the circuit, perhaps one could say I’ve been self-indulgent, merely doing what I most like to do.

However, I also love the music for itself alone. For that reason, I’d like to think that, once my festival days are over, I’ll have left the music in at least as good shape as I found it and, maybe, added something to it.

If so, it sure won’t be in the area of instrumental technique. As my regular readers know, I’m essentially a self-taught musician, having had only a handful of lessons on the piano, my principal instrument, and none at all on the cornet, my main double for nearly forty years now.

I know that I must being doing many things wrong technically. You could throw a pebble in any direction at a festival (but please don’t) and you’ll probably hit a pianist or cornetist with more chops than me.

However, I doubt that you’ll find many musicians on festival stages who know the complete versions (verse, chorus, all the strains and lyrics) to more Dixieland and ragtime tunes than I do. I use a number of rarities in my solo piano/vocal shows. If you’ve seen one, I’ll bet that I played something for you that you haven’t heard live from anyone else.

On the cornet, though I may not hit any high Cs during a set, I know how to play a hot lead horn. When I’m at the helm of a Dixieland combo, we usually manage to raise the temperature.

Also, I’ve played almost all of the instruments in a Dixieland band and have, I think, a reasonably complete understanding of what makes a band come together. Thus, as I believe you’ll hear from fans and other musicians, I can do a pretty good job of running a jam session, of getting a bunch of musicians who’ve never played together previously to sound like we have some interesting routines.

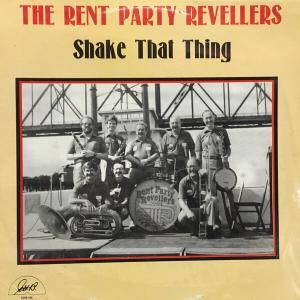

However, there are lots of hot lead horn men who run great impromptu bands and many Dixieland/ragtimers who play seldom-heard titles. If I had to pick a distinctive contribution I’ve made to the music, it would be my national festival/cruise Dixieland band, The Rent Party Revellers, who celebrate our 22nd year on the boards in 2004.

However, there are lots of hot lead horn men who run great impromptu bands and many Dixieland/ragtimers who play seldom-heard titles. If I had to pick a distinctive contribution I’ve made to the music, it would be my national festival/cruise Dixieland band, The Rent Party Revellers, who celebrate our 22nd year on the boards in 2004.

As many of you know, the Revellers are a high-energy revivalist octet. I may be too close to it to judge, but when the Revellers get up and rolling, heading for the goal line on an up-tempo lease breaker, I believe you’d be hard pressed to find many contemporary Dixieland combos that can stay even with us for sheer power, drive and excitement.

Still, being a hot and exciting band is nothing new. The thing that separates the Revellers’ music from that of the others is my view, described in previous columns, of the distinctive abilities that Dixieland musicians have vs. jazzmen in other styles. I try to make maximum use of those skills during Revellers’ appearances.

The result thereof is that, during a given performance, the Revellers make more spontaneous use of different instrumental combinations than any other band in the history of Dixieland jazz. Said another way, we try to show you more ways to explore the potential of the tune than anyone else has. You may disagree, but I think our recordings clearly support those statements.

I must confess, though, that our contribution to the music came along too far down the curve to make any difference. The Revellers first appeared just after 1980 as part of the last big wave of popular new Dixieland bands that focused exclusively on playing top-quality music (as opposed to putting primary emphasis on the “show” aspects of their sets).

By 1980, most Dixielanders in festival bands had reached or passed middle age. They knew what they wanted to play and how they wanted to play it. They were not about to modify their music to incorporate ideas emanating from the next stage.

By 1980, most Dixielanders in festival bands had reached or passed middle age. They knew what they wanted to play and how they wanted to play it. They were not about to modify their music to incorporate ideas emanating from the next stage.

The generations coming along behind us haven’t produced enough Dixielanders to keep the music visible at the national level. Thus, there will be no way to measure whether our music influenced them, and indeed, probably no one acting as historian of the scene to say so if it did.

Even so, the Revellers’ unique contribution to Dixieland is there for anyone who wants to keep score. Perhaps I am immodest to say so, but I can’t help believing it to be a worthwhile one and taking some pride in having produced it.

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

Want to read ahead? Buy the book!

The full run of “Texas Shout” has been collected into a lavishly illustrated trade paperback entitled Texas Shout: How Dixieland Jazz Works. This book is available @ $20.00 plus $2.95 shipping from Tex Wyndham, On request, Tex will autograph the book and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Tex Wyndham’s 3 CD Guide to Dixieland with music and commentary is available for $20 plus $2.95 shipping. The separate CD, A History of Ragtime: Tex Wyndham Live At Santa Rosa, is available for $13.00 plus $2.00 shipping. On request, Tex will autograph the inner sleeve and add a personalized note (be sure to tell him to whom the note should be addressed).

Send payment to Tex Wyndham, P.O. Box 831, Mendenhall, PA 19357, Phone (610) 388-6330.

Note: All links, pictures, videos or graphics accompanying the Shouts were added at the discretion of the Syncopated Times editorial staff. They did not accompany the original columns and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Tex Wyndham.

From roughly 1970-2010, Tex Wyndham was: (1) one of the best-known revivalist Dixieland jazz musicians in the US, as cornetist, pianist and bandleader, (2) one of the best-known ragtime pianists in the US, and (3) one of the most respected critics in the US of Dixieland jazz, ragtime, and related music. He is the only person about whom all three of those statements can be made.