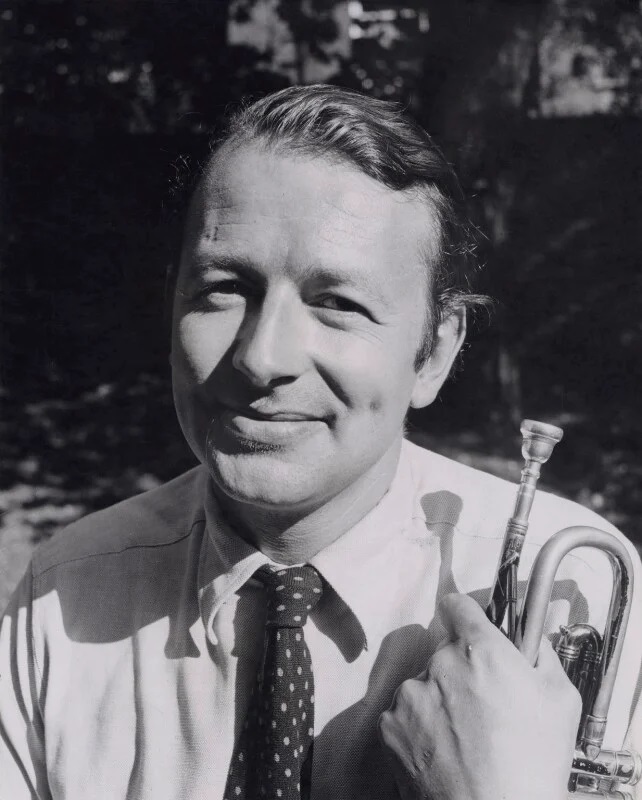

(Credit: National Portrait Gallery London)

In music history, it ranked with Igor Stravinsky’s debut of The Rite Of Spring in 1913 and Bob Dylan “going electric” at the 1965 Newport Blues Festival. In both of those cases, longtime fans were horrified by their idols changing their musical direction. The same thing happened to trumpeter Humphrey Lyttelton during 1954-55 when he decided to gradually abandon his emphasis on 1920s jazz in favor of playing mainstream swing. His altoist Bruce Turner was branded “the dirty bopper” (even though he generally sounded a bit like swing greats Johnny Hodges and Tab Smith) and for a time Lyttelton’s popularity dropped. But as with Stravinsky and Dylan, Lyttelton outlasted his detractors

Humphrey Lyttelton, who had a genial and friendly personality, did not set out to be controversial but he was also not going to be told what he should perform. In fact, the title of his first autobiography (from 1954) summed up his musical philosophy: I Play What I Please. When asked about his musical philosophy by me in 1999 for my book Trumpet Kings, he replied, “I believe that the most important things are, in this order, ‘Get there, do it, pick up the money, and go home.’ Leave abstractions such as ‘art,’ ‘self-expression,’ ‘purpose’ etc. to your subconscious. And for the future, my main goal is to stay upright as long as possible!”

Humphrey Richard Adeane Lyttelton was born May 23, 1921, in Buckinghamshire, England. He first heard jazz on the radio where he enjoyed the London dance bands and was particularly impressed by trumpeter Nat Gonella; Lyttelton was also inspired by Louis Armstrong’s recordings for the Decca label. He started out playing harmonica and, when he was 15, he taught himself the trumpet, only having one lesson in his life. In addition to Gonella and Armstrong, Lyttelton considered his main influences to be Jimmy McPartland, Muggsy Spanier, Henry “Red” Allen, and Buck Clayton.

After finishing school, he had day jobs (including working at the Port Talbot steel plate works) and then spent 1941-46 in the Army. Lyttelton saw action at Salerno, Italy. Reportedly when he landed on the beach, he had a gun in one hand and a trumpet in the other. On VE Day, he made his debut on the radio when he was caught playing his trumpet in a celebration while being wheeled around in a wheelbarrow.

After his discharge in 1946, Lyttelton attended the Camberwell School Of Art where he met clarinetist Wally “Trog” Fawkes, a lifelong friend. An amateur musician at the time who had a day job, Lyttelton was documented playing two songs in 1946 (released many decades later by the Lake label) and then in 1947 he became a member of George Webb’s Dixielanders. Pianist Webb’s group, which had been formed in 1944 and included Fawkes on clarinet, was one of the first British trad jazz bands. Although classic jazz had been played occasionally by some groups in Great Britain in the 1930s and there were jam sessions, Webb’s was among the first fulltime groups to specialize in the idiom. Lyttelton was a key member of the band during its final year. Doubling on trumpet and cornet, Humph was already a solid player whether leading the ensembles or being featured as a soloist. He also played with drummer Carlo Krahmer’s Chicagoans for a period during 1947-48.

Humphrey Lyttleton started leading his own band in 1948 and began recording as a leader. He originally had George Webb as his pianist, trombonist Harry Brown (soon succeeded by Keith Christie who was with him during 1949-51) and Wally Fawkes on clarinet. Keith Christie’s brother Ian sometimes joined in on second clarinet. In 1951 when Christie left to form his own group, the Lyttleton band became a trombone-less sextet. The rhythm section of pianist Johnny Parker, guitarist Freddy Legon, bassist Micky Ashman, and drummer George Hopkinson was unchanged for the next four years and, other than the addition of altoist Bruce Turner in 1953 and trombonist John Picard in late 1954, the personnel of the core band during its most popular period was remarkably stable.

Beyond music, Lyttelton and Fawkes had another partnership. They were both cartoonists and in 1949, Fawkes told the trumpeter about an opening for an illustrator’s job at the Daily Mail where he worked. That became Lyttleton’s day job for the next seven years where he contributed to cartoons that were often satirical, sometimes political, and generally humorous.

While largely unknown in the United States (although Louis Armstrong was a fan and Sidney Bechet recorded with the trumpeter and his band for a 1949 session), Humphrey Lyttleton was the leader of classic traditional jazz in England. He had no close competitors until the rise of Chris Barber in the mid-1950s. Lyttelton and his group recorded at first for his own London Records company and then prolifically for the Parlophone label, making over 170 titles during this period. Their recordings included many songs from the 1920s that found the band (with Fawkes often sounding close to Johnny Dodds) being creative within the classic format.

They did not copy the original recordings too closely, played an occasional original and Dixieland standard, and had their own sound. The music was exciting and fresh, especially for the ears of British jazz fans who had tired of the more predictable swing big bands. Lyttleton became an influential force, giving jazz listeners a contrast to the new bebop music. At a time when traditional jazz was declining in popularity in the United States, Lyttelton’s performances and recordings helped lead to a major revival in England, setting the stage for the trad jazz movement of the next decade.

Even at that early stage, Lyttleton went out of his way to keep from having his music be predictable. He began doubling on clarinet, occasionally playing alongside Fawkes on memorable two-clarinet pieces. He also occasionally expanded his group for recording projects including utilizing extra percussionists (bongo, congas, and maracas) with the Grant-Lyttleton Paseo Jazzband which gave some of the traditional jazz pieces a different sound than expected.

Despite being termed a “dirty bopper” by some Lyttleton fans who did not want the band to change, Bruce Turner not only played alto but was an excellent trad jazz clarinetist who gave Lyttleton a third horn starting in 1953. It was actually not until John Picard joined that the Lyttleton sound began to seriously change, much to the dismay of many of his fans. Lyttleton felt that he no longer wanted to be restricted to 1920s style music. He loved the swing of Count Basie and Duke Ellington as much as he did Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke and he wanted the freedom to broaden his repertoire. By 1955, there were many new trad jazz bands in Great Britain being formed on a regular basis and Lyttelton’s was no longer the pacesetter. It was time to move on.

In late 1955 Wally Fawkes left the band to concentrate on his career as a cartoonist. Ironically at the very next recording session (on Apr. 20, 1956) Lyttleton had the only pop hit of his career, the simple and catchy riff tune “Bad Penny Blues.” His repertoire became more swing-oriented, his rhythm section gradually changed and by 1957 Turner was gone, replaced by altoist-clarinetist Tony Coe and tenor-saxophonist Jimmy Skidmore, with baritonist Joe Temperley joining the following year. While Lyttelton’s own playing style did not change much and he occasionally performed early jazz tunes, he now felt free to play music from the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s. Occasionally he led a big band and during 1957-58 there were tours with the former Count Basie singer Jimmy Rushing.

The rise of the trad jazz movement in England which found such bands as Kenny Ball, Acker Bilk and Chris Barber having pop hits in the early 1960s largely passed Humphrey Lyttelton by. He was quoted as saying that perhaps he should have added a banjo player rather than saxophonists. But he remained a household name in Great Britain and kept busy in many areas.

Lyttleton was a regular on the radio, not just as a bandleader but as the host from 1967-2007 of The Best of Jazz on BBC Radio 2 which gave him the opportunity to play and discuss recordings from all eras of jazz. On musical television shows he was often the host, presenting jazz groups that were often more modern than his. He was a calligrapher and the president of The Society for Italic Handwriting. In 1983, he formed Calligraph Records which reissued many of his earlier recordings. Lyttelton was also a restaurant critic for Vogue, a columnist for Punch, and an occasional cartoonist in later years.

Humphrey Lyttleton gained his greatest national fame as the host of the very popular radio game show I’m Sorry I Haven’t a Clue where his humor was allowed to flourish. He was a regular on the program from 1972 until shortly before his passing 35 years later. He also wrote nine books on jazz including four memoirs and he occasionally reviewed recordings.

Lyttelton did all of this while still performing music, leading an octet, and recording on a regular basis. He collaborated with trumpeter Buck Clayton (one of his favorite trumpeters) on several tours and recordings in the 1960s, had occasional reunions with Wally Fawkes and Bruce Turner, worked and recorded with visiting Americans (including Vic Dickenson, Buddy Tate, and Kenny Davern), often paid tribute to Duke Ellington, and never lost his love for early jazz.

Humphrey Lyttleton, who made his last recordings in 2007, never retired from anything and stayed active in all of his fields up until the end. He passed away on April 25, 2008 at the age of 86. Most of his many recordings are well worth searching for, his books (including his final one Last Chorus) can be found, and there are an assortment of film clips of his playing readily available on YouTube. Humph left behind quite a legacy.

Since 1975 Scott Yanow has been a regular reviewer of albums in many jazz styles. He has written for many jazz and arts magazines, including JazzTimes, Jazziz, Down Beat, Cadence, CODA, and the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, and was the jazz editor for Record Review. He has written an in-depth biography on Dizzy Gillespie for AllMusic.com. He has authored 11 books on jazz, over 900 liner notes for CDs and over 20,000 reviews of jazz recordings.

Yanow was a contributor to and co-editor of the third edition of the All Music Guide to Jazz. He continues to write for Downbeat, Jazziz, the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, the Jazz Rag, the New York City Jazz Record and other publications.