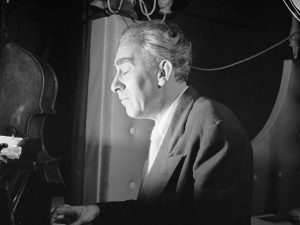

In a word association game, it would not be unusual for the word Swing to be followed by that of Count Basie. For nearly a half-century and the 40 years since, Basie and his big band have symbolized swing. It has always been difficult to listen to Basie’s music and not feel inspired to tap one’s foot. And yet, when the Swing era began with Benny Goodman’s huge success in 1935 and even for a year afterwards, very few outside of Kansas City had ever heard of Count Basie.

William James Basie was born on Aug. 21, 1904, in Red Bank, New Jersey. His father played the mellophone and his mother was a pianist although neither were professionals. Basie’s mother gave him his first piano lessons. He was actually more interested in playing drums, at least until he saw Sonny Greer play in 1919, quickly realizing that he would have a better chance as a pianist. Basie learned to improvise by watching others and playing with several local groups including Harry Richardson’s Kings Of Syncopation.

After freelancing in Atlantic City, in 1920 the 16-year old pianist moved to Harlem where he worked at a variety of musical jobs during the next seven years. Basie met Fats Waller who he heard playing organ for silent movies. Waller taught Basie the organ which he would play on an occasional basis in later years. Another early supporter was Willie “the Lion” Smith who helped Basie find some jobs. He worked with June Clark and Elmer Snowden, was part of the house band at Leroy’s, and went on the road with several vaudeville troupes, backing singers, comedians and dancers including with Katie Krippen and Her Kiddies..

In 1927, Basie was touring with the Gonzelle White Show when they broke up and left him stranded in Kansas City. The young pianist liked what he saw and decided to stay. The all-night jam sessions appealed to him, as did the dozens of establishments that were always in demand for African American entertainers and jazz musicians. Prohibition was completely ignored in the wide-open city and each night was a jazz festival that ran into the early morning hours. Basie felt very much at home.

In 1927, Basie was touring with the Gonzelle White Show when they broke up and left him stranded in Kansas City. The young pianist liked what he saw and decided to stay. The all-night jam sessions appealed to him, as did the dozens of establishments that were always in demand for African American entertainers and jazz musicians. Prohibition was completely ignored in the wide-open city and each night was a jazz festival that ran into the early morning hours. Basie felt very much at home.

He followed Waller’s example and soon got a job accompanying silent films on organ. In 1928 he joined Walter Page’s Blue Devils which was considered the top jazz combo in the Midwest. The band included such future Basie members as singer Jimmy Rushing, trombonist Dan Minor, trumpeter Hot Lips Page, altoist Buster Smith, and bassist Page himself. Despite their artistic success, one-by-one the members of the Blue Devils were lured away by Bennie Moten whose Kansas City Orchestra could pay more lucrative salaries. The Blue Devils only had one recording session and by then, Basie was already with Moten.

Since Bennie Moten was also a pianist, it was rather unusual that he would hire Basie, but he was very impressed with his piano playing. In fact, although Moten would make occasional appearances playing with his orchestra, starting with the session of Oct. 23, 1929, Basie would be the only pianist to appear on records with Moten’s band.

At the time, Basie (who was soon given the lifelong nickname of Count by a radio announcer) sounded a bit like a protégé of Fats Waller. His stride playing, while not on the virtuosic level of Waller and James P. Johnson, was excellent and that, coupled with his friendly nature, made Basie popular in Kansas City. In addition to playing and recording with Moten, he was part of the legendary late-night jam sessions.

Basie was on eight record dates with Moten during 1929-31 which resulted in 30 songs (not counting alternate takes). He was given a fair amount of solo space (including on a number called “The Count” that preceded that becoming his name) and he took his only recorded vocal, scatting on “Somebody Stole My Gal.”

During the worst part of the Depression, on Dec. 13, 1932, the Bennie Moten Orchestra had their final and greatest recording session. By then the band featured such notables as trumpeter Hot Lips Page, both Dan Minor and Eddie Durham (doubling on guitar) on trombones, and tenor-saxophonist Ben Webster in addition to Basie, Walter Page, and Jimmy Rushing. On the ten titles recorded that day, the band often hints at the future Count Basie Orchestra, particularly on “Moten Swing,” “The Blue Room,” “Lafayette,” “Prince Of Wales,” “Milenberg Joys,” and “Toby.” They were playing swing before that word was used to name both a style and an era.

While Count Basie broke away from Moten a few times to lead short-lived bands, he was with the Moten Orchestra when its leader died from a botched tonsillectomy on Apr. 2, 1935. The orchestra was taken over by Bennie’s brother, accordionist Buster Moten. Basie soon went out on his own, at first leading a trio and then a small group comprised of the nucleus of the Moten Orchestra which was called the Barons Of Rhythm. Basie’s band was soon considered the most impressive jazz group based in Kansas City. Through a stroke of luck, the young record producer John Hammond, while switching dials on his radio, heard the Basie Orchestra and soon flew to Kansas City to check them out in person. While he was not quite fast enough (Basie signed to the Decca label before Hammond arrived), he was able to convince Basie that he should take his band East to Chicago and New York.

Count Basie had greatly simplified his own piano style and was forming a new type of rhythm section. The foundation of Basie’s music which he nurtured and developed during his Kansas City years would always be the blues. In 1936 he was playing a lot less than other stride pianists, making dramatic use of space and perfectly placing his notes to maximize swing. The cool and light sound that he created made it essential for him to have a strong walking bass player and Walter Page was a perfect fit. Drummer Jo Jones accentuated Basie’s innovations by de-emphasizing his bass drum in favor of the hi-hat cymbal which gave him a much lighter sound than the drumming of Gene Krupa. With Claude Williams playing rhythm guitar, the rhythm section uplifted the entire band.

While Hot Lips Page was soon lured away by manager Joe Glaser who signed him to a contract as a leader, his replacement was Buck Clayton, a trumpeter with a distinctive sound who had a soft (often muted) sound but could also hit surprising high notes. Most important among the horn players were the contrasting tenor-saxophonists. Lester Young had an innovative cool sound and a floating style while Herschel Evans was influenced by the harder tone of Coleman Hawkins. They often engaged in tenor battles that ended up being ties due to their different approaches. With Jimmy Rushing (the greatest of the male jazz singers working with swing era orchestras) singing the blues, in 1936 Count Basie had one of the very best jazz bands even if he was still largely unknown outside of Kansas City.

Count Basie’s band was actually only nine pieces when John Hammond met him. Many of its songs were based on riffs that were made up spontaneously on the bandstand. That ad-lib spirit would remain part of the Basie sound throughout the next 13 years. But to succeed in the swing world, Basie would have to expand his orchestra to 13 pieces. When his group left Kansas City in early-1936, they performed at Chicago’s Grand Terrace Ballroom and struggled. Not all of the musicians read music that well and it was a difficult task playing arrangements behind singers, dancers and specialty acts.

While in Chicago on Nov. 9, 1936, a small group from the band recorded under the name of Jones-Smith Incorporated. The quintet was comprised of the excellent if now forgotten trumpeter Carl “Tatti” Smith (subbing for Buck Clayton), Lester Young, Basie, Page and Jones. Their four numbers had brilliant playing from Young (particularly on “Lady Be Good”), two fine vocals by Jimmy Rushing, and introduced the Basie sound to a wider audience.

1937 was the year that Count Basie’s orchestra started to catch on. They began to record for Decca including Basie’s theme song “One O’ Clock Jump” (which soon nearly every swing band was playing), “John’s Idea,” “Good Morning Blues,” and “Topsy.” Freddie Green replaced Claude Williams as the band’s rhythm guitarist, Eddie Durham contributed some classic arrangements as did Skip Martin, Benny Morton joined on trombone, and Billie Holiday spent a few months as the band’s female singer. Due to being signed to another label, Lady Day did not make any studio recordings with Basie although a couple of songs from broadcasts (including “Swing Brother Swing”) were released decades later.

Other bandleaders took notice of the Basie sound and began to be influenced by his rhythm section’s lighter sound and his orchestra’s easy-going if hard-driving swing. Benny Goodman was a fan and at his famous Jan. 16, 1938 Carnegie Hall concert, he performed his version of “One O’Clock Jump” and invited Basie, Lester Young, Buck Clayton, Freddie Green, and Walter Page to be part of his jam session version of “Honeysuckle Rose.”

1938 brought a second major trumpet soloist to the band in Harry “Sweets” Edison along with trombonist Dickie Wells and singer Helen Humes. Among Basie’s classic recordings of that year were Jimmy Rushing’s feature on “Sent For You Yesterday And Here You Come Today,” “Every Tub,” “Swinging The Blues,” “Doggin’ Around,” Herschel Evans’ ballad feature on “Blue And Sentimental,” “Jumpin’ At The Woodside,” and “Shorty George.”

From that point on, success followed success. While Basie would not have million selling records like Artie Shaw, Glenn Miller and Harry James, his recordings sold well, his performances were well attended, and his band was highly rated. Few could outswing them and the orchestra usually sounded like a large band that had the freedom of a small combo.

Once the Count Basie Orchestra had begun to solidify its sound in 1937, there was little real change during the next dozen years despite changes in personnel and the development of other styles of music. There was no real reason for any major alterations because the infectious Basie sound was played with enthusiasm and creativity.

A major blow was suffered when Herschel Evans unexpectedly passed away in Feb. 1939. His permanent successor was Buddy Tate who stayed a decade and had similar influences as Evans although he also had his own distinctive sound. Otherwise the personnel was pretty stable. Rushing and Humes gave Basie two major vocalists who could sing blues, ballads and swinging standards. The band never had a need for a commercial pop vocalist as did many other swing orchestras of the time. The trumpet section added a third fine soloist in Shad Collins, the sax section (in addition to Young and Tate) included the lead altoist Earl Warren and baritonist Jack Washington, Benny Morton and Dickie Wells shared the trombone solos (Vic Dickenson took Morton’s place in 1940) and the rhythm section remained unchanged.

Basie had some small group sessions (including a combo date that resulted in “Lester Leaps In” and “Dickie’s Dream”) but was primarily heard with the full band, often playing arrangements by Durham, Jimmy Mundy and Andy Gibson. Edison’s “Jive At Five,” “Rock-A-Bye Basie,” “Taxi War Dance,” “Clap Hands Here Comes Charlie,” “Tickle-Toe,” and “Broadway” were some of Basie’s best recordings of 1939-40. In 1940 the addition of trombonist Vic Dickenson and altoist Tab Smith made the band even stronger.

Benny Goodman was such an admirer of Basie’s sound that in mid-1940, he toyed with the idea of breaking up his orchestra and forming a combo with Basie, Buck Clayton, Lester Young, the Basie rhythm section and guitarist Charlie Christian. Although that never happened, a rehearsal by that group of all-stars resulted in five performances that were released in the 1980s on a collector’s LP. Basie also guested on a series of recordings by the Benny Goodman Sextet.

By late 1940, the Count Basie Orchestra was up to 16 pieces but there was one major change. Lester Young left the band in December. It has long been rumored that he simply did not want to record with the band on Friday the 13th although that is probably a myth. Chances are that he wanted to try his luck as the leader of his own combo. A month later Don Byas took his place. Even without their top soloist, the Count Basie Orchestra continued having success through 1941 and 1942, appearing regularly on radio and before large crowds. They welcomed guest Coleman Hawkins on one session, accompanied Paul Robeson on the two-part “King Joe,” and recorded “Harvard Blues” (featuring Jimmy Rushing) and Buck Clayton’s arrangement of “It’s Sand, Man.” When Helen Humes departed, she was replaced by the rewarding if underrated Lynn Sherman.

Count Basie was able to continue on despite three potentially major obstacles during the 1942-46 period: World War II, the musicians union’s recording strike, and the rise of bebop. While the recording strike resulted in no new Basie recordings from mid-1942 until late 1944, he remained a fixture on the radio, made some memorable Soundies (three-minute films that were viewed on video jukeboxes), and continued being a fixture in clubs. Lester Young returned for a period during 1943-44 before being one of the Basie sidemen who were drafted along with Jo Jones and Walter Page; the latter two returned to the band after the war ended. Young’s place was filled during the 1944-49 period by three brilliant soloists: Lucky Thompson, Illinois Jacquet and Paul Gonsalves.

Buck Clayton departed but Joe Newman was his excellent successor in the trumpet section. And while an occasional arrangement hinted at bebop, the Basie sound remained intact and fresh. Through it all, there was no drop in the band’s quality. In fact, the 1946 version of the band with Jacquet (who was quite exciting on “The King” and “Mutton Leg”) trombonist J.J. Johnson, and Edison, Newman and Emmett Berry in the trumpet section was one of Basie’s finest.

The decline in the public’s interest in swing, the rise of rhythm and blues and pop singers, the Dixieland revival, and the introduction of television made it difficult for any big band to survive the late 1940s, and their chances were not helped by a second musicians recording strike in 1948. Basie’s orchestra by then had undergone a lot of turnover with Buddy Tate, Walter Page, and Jo Jones departing although trumpeter Clark Terry was a promising newcomer. But what really resulted in his band breaking up in late 1949 was Basie’s financial situation. He had a gambling problem and made some bad business decisions that resulted in him finding it difficult to make the payroll of his 19-piece orchestra. With great reluctance he broke up the Count Basie Orchestra in August, the month in which he turned 45.

Count Basie’s remarkable comeback as a big band leader with his “New Testament” Orchestra will be covered in the next issue.

Since 1975 Scott Yanow has been a regular reviewer of albums in many jazz styles. He has written for many jazz and arts magazines, including JazzTimes, Jazziz, Down Beat, Cadence, CODA, and the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, and was the jazz editor for Record Review. He has written an in-depth biography on Dizzy Gillespie for AllMusic.com. He has authored 11 books on jazz, over 900 liner notes for CDs and over 20,000 reviews of jazz recordings.

Yanow was a contributor to and co-editor of the third edition of the All Music Guide to Jazz. He continues to write for Downbeat, Jazziz, the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, the Jazz Rag, the New York City Jazz Record and other publications.