Jeff Barnhart: Hal, we left off our discussion in Part One with a brief analysis of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band and their way of performing a tune: boisterous, loud, fun, rambunctious, but with little improvisation and virtually no soloing; the band was performing in a style my good friend Dan Levinson refers to as “rag-a-jazz,” that is, a transitional style between ragtime and jazz.

Contrast the ODJB’s style with the scene down in New Orleans at the time. There was a prismatic array, of repertoire, style, dynamics and performance venues. The repertoire for picnics, weddings, and society dances included waltzes, quadrilles, polkas, schottisches, mazurkas, and more to accompany the many traditional European dance steps still popular as the 19th century gave way to the 20th. It was in the late-night halls where the real jazz, slow drags, and blues were being played. One of the most notorious of these, Funky Butt Hall, served as a rough dance hall until Sunday morning when, as bassist Ed Garland averred, there would be only 20 minutes between “functions,” with dancers staggering out while worshippers swooped in to set up for their church service.

In Funky Butt and other halls, the bands would draw a tune out, keeping that tune going to fill the floor. As the late night gave way to early morning, the tempos would slow. Baby Dodds reminisces, “We took our time and played the blues slow and draggy…it was so draggy, sometimes, people would say it sounded like a dead march.” This practice was not limited to late-night dance halls; Albert Burbank describes a typical daytime (indoor) picnic, where the band would arrive at 11 am and play for six to seven hours. He mentions, “Tempos were slower. Not a lot of solos taken, although sometimes players would take their horns down to rest.” He reveals that after each number, the band would take a five-minute break. Most likely these were not tunes lasting only three minutes!

Hal, do you have any stories or insights regarding the crucial connection between jazz and dancers in early NOLA? Also, could you tell us a bit about the importance of dynamics in the music, especially referencing King Oliver as you did during one of our conversations?

Hal Smith: From everything I have read about New Orleans from the 1890s to WWII, dancing to live music was an activity that was enthusiastically embraced by everyone who could shake a leg. You mentioned Funky Butt Hall and there were other dance halls which catered to a “tough” clientele. But at the other end of the society scale, King Oliver played for “subscription” dances at Tulane University, while Papa Celestin’s and Monk Hazel’s bands played for dancers at the Bienville Hotel and Piron’s Orchestra kept the dancers happy at the New Orleans Country Club.

And there were lots more dance venues throughout the city! Joe Oliver must have figured out pretty quickly that the high steppers didn’t want to be blasted off the dance floor. By the time he was leading the Creole Jazz Band at the Lincoln Gardens in Chicago, it was said that the band could play so quietly that you could hear the dancers’ feet moving across the floor.

It’s beyond the scope of our column this month to dwell on the impact Irene and Vernon Castle had on the creation of the society dance craze, or to discuss pioneer bandleader Art Hickman’s influence regarding instrumentation, repertoire, style, and presentation during a dance band “gig,” but they, among others, fueled the engine of dancing as a burgeoning big business. What had started in small, unassuming community function halls and Elks Clubs was now moving into ballrooms built specially to accommodate dancing. The higher-level hotels, not wanting to lose out on the business, started to build and devote ballrooms to host dances. Even amusement parks and casinos started offering ballroom venues! As these places grew in number, the demand for quality jazz and dance bands and orchestras mushroomed. At the height of the Swing era, hundreds of bands, large and small, were crisscrossing the country to fulfill engagements packed with dancers.

Even theaters would have bands perform before or after the film. One of the most famous was the Paramount on Times Square in NYC. In March 1937, Benny Goodman’s Orch. was scheduled for a two-week run. The film ended, the band came into view on an elevatable orchestra pit, started up their theme, “Let’s Dance,” and the place erupted! There was dancing in the aisles, and even on the stage, despite the movie usher’s best efforts; high-school age kids were now experiencing music they had previously only heard on records. In fact, the Paramount and other theater venues made the music available to a much broader spectrum of the public; hitherto the best bands were playing the aforementioned ballrooms and hotels where prices were steep, alcohol was being consumed, and the clientele was mostly well-heeled adults.

Even theaters would have bands perform before or after the film. One of the most famous was the Paramount on Times Square in NYC. In March 1937, Benny Goodman’s Orch. was scheduled for a two-week run. The film ended, the band came into view on an elevatable orchestra pit, started up their theme, “Let’s Dance,” and the place erupted! There was dancing in the aisles, and even on the stage, despite the movie usher’s best efforts; high-school age kids were now experiencing music they had previously only heard on records. In fact, the Paramount and other theater venues made the music available to a much broader spectrum of the public; hitherto the best bands were playing the aforementioned ballrooms and hotels where prices were steep, alcohol was being consumed, and the clientele was mostly well-heeled adults.

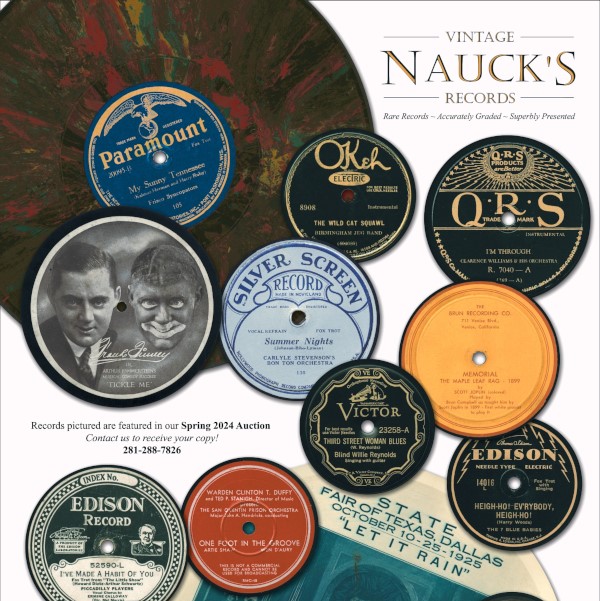

Seemingly nothing could stop the marriage twixt jazz and dance, not even Paul Whiteman’s efforts to concertize the music with his “Symphonic Jazz” or the never-ending threat of new technology in the form of Edison cylinder phonographs, Victrola Talking Machines, et al, and then radio—although the latter, while encouraging people to enjoy top-quality entertainment at home, did offer band remote broadcasts which were an excellent way to build a band’s exposure and reputation. So what happened? How did it wane and eventually all but cease?

Seemingly nothing could stop the marriage twixt jazz and dance, not even Paul Whiteman’s efforts to concertize the music with his “Symphonic Jazz” or the never-ending threat of new technology in the form of Edison cylinder phonographs, Victrola Talking Machines, et al, and then radio—although the latter, while encouraging people to enjoy top-quality entertainment at home, did offer band remote broadcasts which were an excellent way to build a band’s exposure and reputation. So what happened? How did it wane and eventually all but cease?

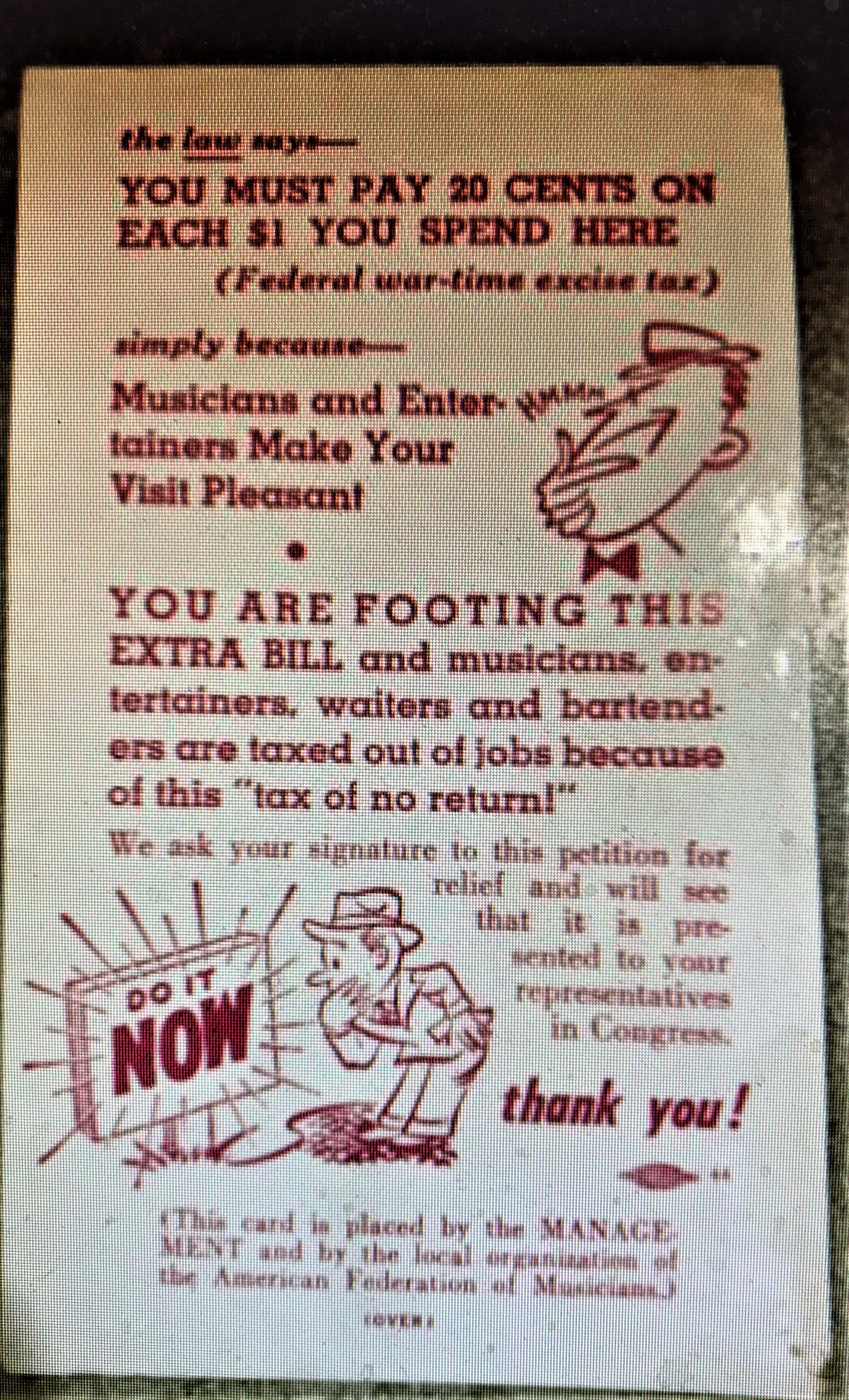

HS: World War II and the Draft certainly took away a lot of dancers (and musicians), but the worst possible development that affected dancers and musicians alike was the Cabaret Tax.

That federal tax was imposed in 1944 and required a 30 percent excise on the receipts at any establishment that offered food and drink for sale and permitted dancing. But if a venue served food and drink and offered entertainment but did not permit dancing … the tax was not imposed. You can imagine what happened next, but you don’t have to. Just take a listen to the 1940s recordings of Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, and other young musicians who performed music that was definitely not for dancing!

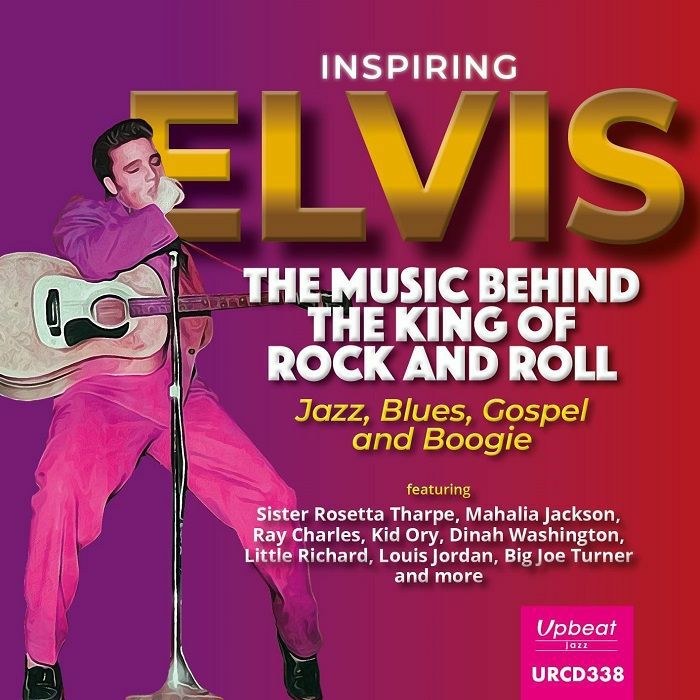

In the late 1940s, Lu Watters’ “Hambone Kelly’s” provided plenty of space for dancers, but Hambone’s was an exception. At clubs across the US, audiences endured cramped table seating at venues like Eddie Condon’s and Club Hangover. The music was great, but there was not even a postage stamp-sized dance floor. Dancing to swing and traditional jazz was dealt another blow in the 1960s, as Rock ‘n’ Roll dominated the music scene. Except for Turk Murphy’s “Earthquake McGoon’s,” the type of venue most likely to host a traditional jazz band during this time was a pizza parlor: a subject we should explore in a future column!

JB: Although the exorbitant rate of the cabaret tax was relatively short-lived, it did end up putting a lasting cramp on dancing to jazz. As dancing disappeared, musicians were more concerned with playing for themselves than pleasing an audience (witness the Bop movement to which you alluded and bandleaders like Stan Kenton desiring his music to be heard in a concert, not dance, setting). Although there were audiences interested in experiencing jazz with their ears more than their feet, these numbers would dwindle as jazz continued to fade into the background of the American soundtrack.

In bandleaders’ own words, we can glimpse why some dance orchestras continued to thrive, albeit mostly those with the least amount of jazz content. Lawrence Welk avowed, “Our own success speaks for itself. I believe it came because we never forgot that it was the dancers who paid our salaries and we always tried to give them what they came to hear.” Guy Lombardo insisted, “Bandleaders should not attempt to be educators. People who come to see us pay to be entertained—not educated!” The King of Swing (and you couldn’t find more jazz content than in Goodman’s Orchestra) really had a handle on the scene, and this contributed to his longevity. Himself an excellent dancer, as accounted by John Hammond, Benny averred in Stanley Dance’s World of Swing, “When people are dancing, you couldn’t play one piece for ten minutes. I don’t know whether they would have left the floor, but you had to give them a variety of tempos and tunes. Usually you’d play five or six numbers in a set; each one would be about three minutes.”

Our story does have a happy conclusion, however. Despite all of the challenges we’ve described, over the past 30-odd years swing dancing has become a craze once again. Aided, in part, by groups that mixed brassy jazz with guitar rock, such as the Cherry Poppin’ Daddies and Brian Setzer among others, young people had their first taste of moving to a swinging beat. They researched the history and learned the steps, but also soaked in the entire aura. To play one of their dances is to step back in time to what I imagine the Savoy Ballroom in New York was like at the height of the dance band era. As our esteemed editor commented (here I paraphrase): “Whenever I see crowds of twenty-somethings in baggy pants, vintage dresses, hats and ties, I know there’s a swing dance event nearby!”

While there will never again be a conflagration of dancing jazz events supporting hundreds of bands, a steady bonfire has been created that is supporting dozens of swing revival bands worldwide. Once we are on the other side of this “virus vacation,” I hope it will burn again. Long live the Swing Dance Societies and the venues and bands that keep them jivin’!

Hal, I had the lion’s share of space in this month’s column. I look forward to handing the reins over to you for our next topic as you lead our readers and me into the wonderful world of Bob Wills!

Visit Jeff Barnhart’s Website (www.jeffbarnhart.com) and Hal Smith’s (www.halsmithmusic.com) for information regarding recordings and upcoming engagements.