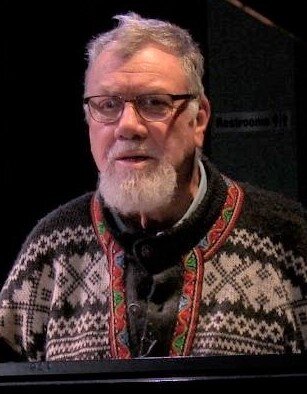

Pianist Ray Skjelbred is now in his 60th year as a professional jazzman. In this first of a two-part interview, he discusses his formative years, his discovery of jazz, and the early development of his piano style.

John Ochs: For most of your years as a musician you’ve lived in Seattle, WA or the Bay Area in northern California, but the city you seem to associate yourself with most closely is Chicago. Why is that?

Ray Skjelbred: Well, I’m from Chicago, and I grew up on the North Side in the 1940s and ’50s. I don’t think of myself as being particularly connected to music when I lived in Chicago. I remember playing family records of the Victor Military Band, Norwegian dance music, Roy Rogers, Bing Crosby, and things like that ‒ but there wasn’t any jazz connection. That connection came about by listening to music after I left Chicago. My mother played a little piano by ear, although I never heard it much because we didn’t have a piano in our apartment. It was something I heard her play later on when I had a piano.

So, I never played piano or knew anything about jazz then. I’m Norwegian, and I played accordion. A guy was handing out leaflets advertising accordion lessons one day after school when I was eight years old. I took a leaflet home and started to take lessons. I’m not entirely sure why. I just did it because it happened to be in front of me. I had two different accordion teachers, one was for lessons and another for a little accordion band I played in. I guess I must have been okay. I can’t remember. It was just a kind of a blur in my memory in some ways, although I did it for years.

Did you ever present concerts or play in school for talent day?

Yeah, I remember, probably once a year, and, of course, I would play these sort of semi-classical pieces written for the accordion. And I remember some other kid played popular songs, and I think everybody liked his playing. That’s okay, though.

So music wasn’t your primary interest in grade school?

No, I wasn’t interested in music at all. I was mostly interested in baseball and watching the Cubs and playing baseball and playing baseball games. That was pretty much it, and even what I read was all baseball. The summer when I was 14, I took the bus to Wrigley Field almost every day, arriving early for batting practice and staying late for autographs. That was the year Ernie Banks hit 44 home runs and became a star.

You left Chicago as a teenager in the mid-1950s when your family moved to Seattle. How was it you became aware of traditional jazz?

Well, probably the very first thing was that I liked to listen to faraway radio stations at night and see where they were from. One night I bumped into “Mood Indigo” by Duke Ellington and I didn’t know anything about that at all. It’s not like that single thing changed my life, but I really liked it, so I was ready the next night I heard something like that to be really interested in it.

And so, about 1958 I bumped into a program on station KTAC in Tacoma which was fortunately run by somebody who had good taste in jazz, Terry McMonagle, and I would sit with my typewriter and type out all the names of the bands and songs and learn things from him week after week. I kind of felt like I was in a vacuum, like I didn’t know about anyone or anything except these things that sort of caught my attention. I tried to simulate them a little bit on the accordion, and although I wasn’t really making the right sound, I was starting to play a little jazz on my own.

I don’t remember exactly what I was playing. I was fooling around with some Jelly Roll Morton songs and things like that. I didn’t quite really know what I was I was doing, and I didn’t have a very good sense of chord directions. I was picking around on melodies quite a bit, and that was actually before I started playing the piano at all, so I can’t remember what songs I played.

At the time, you didn’t own any recordings? You just played tunes off the radio?

Yeah, and then I started to buy some recordings, and several different things then combined in my life. In 1959, I met Bob Graf, who had a lot of recordings and knew a lot about jazz. This is in Seattle. He introduced to me a lot of musicians through his recordings. About a year later, his wife, Sylvia, ran into Mike Duffy, a bass player, while junking for records at Goodwill, so I met him, and before long I met a whole bunch of his friends. I still didn’t play piano at all. I was playing a little accordion, and I was trying to play washboard, but I wanted to play piano.

So we went down to Pioneer Square in downtown Seattle, and I met Johnny Wittwer playing in a band down there. He was just starting to teach piano at that point. Bob Gilman, another piano player, and I were his first two students. I was just a beginning piano player, but I wanted to go straight into playing jazz, and Wittwer was very helpful in giving me some traditional piano instruction, but at the same time showing me all kinds of things that I was asking him about so I could cut the search a little bit short. It was really great to meet him.

How did you decide on piano as your instrument?

Well, I guess because I had been playing the accordion it seemed like the logical next step, especially the way the right hand is played in both instruments, but also because I had heard piano players that I liked on Terry McMonagle’s radio show. Sometimes he would go to San Francisco and buy records of people who were playing down there, and that was a real turning point because I wanted to hear live people playing things. The live person I heard on his show was Burt Bales, who was playing at Pier 23 in San Francisco where I sometimes play now. So I headed down there the summer of 1959 when I was 18, and Burt and I became friends from that time on. I was excited by the fact that someone like that who played the way I wanted to play was around in the world at that time, and I think that just led me to conclude I wanted to play the piano.

What was it that attracted you to Burt Bales’ piano style?

Well, I don’t know exactly how to say it. He had a very warm sound. He was best known for playing ragtime and Jelly Roll Morton, and he did that just wonderfully, but the biggest thing about Burt Bales was the way his hands touched the keys, All the notes had a lot of shading, loud and soft, and blues edges, and it was very beautiful playing, and that’s what struck me first. I guess I can also say that you’ve made a film of me talking about a lot of these same things. It’s worth mentioning the Piano Jazz ‒ Chicago Style film because it encapsulates some of the feelings I had about Burt Bales also.

When did you begin to focus on a piano style or develop what is now recognized as your style?

It’s hard to be sure because it sort of kept changing a little bit along the way, but I’d say the first time I really played piano, which was actually before the lessons with Johnny Wittwer started, I would sneak into buildings that had pianos like Eagleson Hall in the University District, and I’d go in and I could kind of pick out these Jimmy Yancey-like things, very simple blues playing. So, right from the very beginning, it struck me that playing blues was the most important center of playing jazz and that I always wanted to have blues music in what I played.

And shortly after I had been listening to Yancey records, I also started hearing Art Hodes records. So I really became attached to Art Hodes’ blues playing, and it was exciting because he was a jazz musician and you would always hear blues in what he was doing. And as one of the highlights of my beginning playing, I remember that when I was on my 21st birthday Johnny Wittwer had written to Art Hodes and asked him if he would send me a birthday card, and Hodes wrote to me. So that was kind of a thrill and that was kind of my beginning of how I wanted to play. You know, it went from listening to Jimmy Yancey to Art Hodes and Burt Bales, all sort of running together in my head.

About how long did you study with Wittwer before you started playing professionally?

I started taking piano lessons in 1960, and by 1961 I was playing jobs. I mean I went from zero to being a working musician in one year, and it was really because of my intense desire to be able to do that, and his help. He showed me a lot about chords and sequences and alternate ways to do things harmonically, and how to play time. And we played duets a lot, which he thought was a good way to learn how to play music with other people. So all that paid off, and I just spent endless hours working on it, and at the same time, having met Mike Duffy, I met all of his friends who played jazz, including trumpeter Bob Jackson and trombonist Bob McAllister. They were all his high-school friends.

They went to Shoreline High School north of Seattle and you went to Franklin High in south Seattle, so they lived all the way across town, right?

Yeah, I was the one outlier, and you know when I first wanted to play music with those guys I played washboard. I mean I didn’t play piano yet, and then as I got a little more into it, I started playing a few solo piano jobs in 1961, as well as some duet work with Mike in Denver. And before that there were various combinations of people, groups that would get together and play. We played a couple of shows at the University of Washington, like annual shows they had, but it was a floating combination of people in 1962 that finally settled into the group that made up the Great Excelsior Jazz Band.

At the same time you were learning about jazz and meeting the guys in the Great Excelsior band, you were earning a degree in English and beginning a teaching career. Did the two worlds conflict or did one complement the other?

Jazz and literature were like the same thing to me. It was a very exciting time of discovery, and I wanted to absorb it all.

What are your most vivid memories about your time with the Great Excelsior band?

The Great Excelsior Band was the beginning of band-playing for me. It was my band, and when we began we played at a tavern in West Seattle during the World’s Fair. Then we played many places after that through the years from 1962 to 1969. When I moved to the Bay Area, Bob Gilman took my place. A highlight for us was our recording for GHB in 1965 when Claire Austin was singing with the band. This recording included the basic band of Mike Duffy, bass; Bob Jackson, cornet; Bob McAllister, trombone; Dick Adams, clarinet; Bill Lovy, guitar; and Howard Gilbert, drums.

Tell us about your trips from Seattle to the Bay Area and the progression of how you finally decided to move down there.

Well, as I said, the first trip was in 1959, and the main person I saw was Burt Bales at Pier 23. I also saw the Great Pacific Jazz Band with Sanford Newbauer on trombone, Charlie Sonnanstine on trumpet, Roy Giomi on clarinet, Dick Lammi on tuba, Robin Wetterau on piano, Loyd Byassee on drums, and Lee Valencia on banjo. It was fun to see them. They played in an old roadhouse at Muir Beach out by the ocean. It was like down-home music. They loved what they were doing. They hardly made any money. It kind of defined how I always looked at music. You do the right things for yourself and you hope to make somebody else happy by listening to it, but it wasn’t commercial in any way.

At that point, I didn’t have too much to say to them, but in various ways I got to know a lot of them over the years. Lee Valencia became a good friend, and Dick Lammi ‒ I don’t know anyone who knew him real well ‒ but I was interested in him. He was an eccentric personality, and he also had been Johnny Wittwer’s roommate at Hambone Kelly’s when Johnny played in the Lu Watters band there. So I had some knowledge of him. And Sanford Newbauer became a friend.

There were a lot of subsequent trips. It wasn’t until 10 years later I decided to move to the Bay Area. I just felt like I needed to be there. There were a lot of people I wanted to play music with, that I wanted to learn from. I wanted to be part of it, and in particular the first friendship that developed in Berkeley was with banjo player Dick Oxtot, and from him I met lots of other people I wanted to play with, like Bob Mielke on trombone and Bill Napier on clarinet. I just wanted to be part of that scene and play with all the people I had listened to on record from a distance. It was just kind of amazing that they all became my friends. I was very fortunate to be able to fit into everything.

When did you meet Jim Goodwin, the cornetist?

I met Jim in 1967, I think it was. I started playing jobs with Monte Ballou’s Castle Jazz Band in Portland, and Jim would be on some of those jobs. We hit it off right away, and one time I was staying down there overnight, and I heard him play differently when just the two of us were at his house playing piano and trumpet. He sounded closer to the way I wanted to play than we had been doing with Monte. He was playing more like Wild Bill Davison, and I started playing like Jess Stacy, and it was a discovery we made about how our music fit together.

So I played jobs in Portland with him, and he came up to Seattle and played some things up here with me. This was during the time the Great Excelsior band was playing and Bob Jackson, our trumpet player, was beginning a conscientious objector alternative service so Jim Goodwin started filling in on cornet with us, and we played together here and there, Portland and Seattle. And then after I moved down to Berkeley, Jim packed up from Portland and moved down to Berkeley about a week later. So that began our long association.

You mentioned Bob Mielke, Oxtot, Bill Napier. I know there were a lot of other people you were associated with …

Oh yeah, that was quite a world. I played in a lot of bands over the time I lived there, my own bands and bands of other people. If I didn’t have a regular band and needed to put one together, I might say to myself, “Well, who can I get on clarinet?” I could ask Bill Napier or Bob Helm or Ellis Horne or Bunky Colman or Phil Howe or Richard Hadlock. I mean it was a wild and full world of wonderful musicians, and I was very blessed to be able to work with all of them.

I’ve made a list of some bands I played with and people I accompanied in the Bay Area. They include Bob Mielke’s New Bearcats, Dick Oxtot, Ev Farey, Ted Shafer, Lynn Hall, Barbara Lashley, Bob Schulz, Turk Murphy, Barbara Dane, Port City, Phil Howe and John Gill, as well as my own groups, the Berkeley Rhythm, the Port Costa Yeti Chasers, and the Monogram Boys.

Those bands represent quite a cross-section of music. How would you describe the different styles of traditional jazz being played in the Bay Area then? And did you have any trouble adapting to them?

There were many styles of traditional jazz in the area and I felt I had the background and instincts to play comfortably with all of them. However, I felt most at home with what I think of as the East-Bay sound. It was looser and more of a blend of early swing and blues as an essential sound. My Berkeley Rhythm band was a good example of that kind of approach and also my music at the Bull Valley Inn in Port Costa where I played seven years, mostly with Jim Goodwin on cornet, but with many others joining in. At various times we had guests like Bob Mielke, Richard Hadlock, Mike Duffy, Byron Berry, Bob Short, John Smith and Bert Noah. It was loose and wonderful.

What are your favorite memories of specific performances or gigs while living in California?

They don’t necessarily include me, but I developed over time a great passion for the music of Joe Sullivan and Jess Stacy and Earl Hines, and memories I have of them are very powerful. I guess when I drove Joe Sullivan to Richard Hadlock’s kindergarten class and it turned out to be the last time Joe ever played. He played “I Got It Bad and That Ain’t Good,” for the class. And when he did, a kid raised his hand and said, “You’re not supposed to say ‘ain’t.’” And Joe said, “Well, you’re right, but it’s just a song title.” When I drove him home, he seemed old and tired. And we talked about piano playing, and he said, “Our mothers paid good money for our piano lessons, and what did it get us?” He was pretty down about things, but I had a lot of interesting talk with him that particular day about music and life.

I developed a good friendship with Jess Stacy, and I’ve told the story before about when I first met him. It was at the Sacramento Jazz Festival, and there was a band set to play which asked if I would sit in because their piano player wasn’t there, and I said, “No, I don’t think I want to.” Then they asked Jess, and he turned them down too. And since I was playing with a band in the next set in the same building, I was standing there watching them, and Stacy was too. And it was silent for a while, and finally he said to me, “How would you like to be playing in that band right now?” And it just broke me up. I thought it was so funny because he was hearing the same music I was hearing, like some awful Dixieland band, and both of us would rather not have been part of that band. He was very subtle and very quiet, and you know, another guy who defines the people I like and who played the way he wanted to play and didn’t really try to sell himself in any way to anybody. Jess Stacy was a wonderful man.

I also knew Earl Hines. He lived in Oakland and I followed him whenever he played locally, although he traveled mostly. And one night I was playing in the Bancroft Lounge on Shattuck Avenue in Berkeley when Hines walked in. He had been to a seminar that day at the University of California where he had just met the singer with me, Barbara Lashley. She was a wonderful vocalist with a style reminiscent of Maxine Sullivan, the great swing singer. And Hines came to see her, and he stayed to see me and her, and I thought when he came in, “What do I do now?” Well, I said that to myself, but as if he had heard me he said, “You’re drinking on Father Hines.”

Those are some things that stand out. And also, the day when Art Hodes was in town and there was a little party where he and I played duets together. It was really satisfying to be able to play with Art Hodes. That was a pretty memorable time playing music.

And my playing is full of memories of individual people that I played with ‒ how Bill Napier was endlessly wonderful, the trumpet player Jack Minger was wonderful, and everything I did with Bob Mielke was wonderful. I don’t know if I’m picking out a particular memory or not, but it was just always a thrill to hear and play with them.

John Ochs is a jazz fan and record collector who first met Ray Skjelbred at a Seattle Folklore Society concert in 1976. Since then, he has produced an LP, several CDs, and an award-winning film featuring Skjelbred’s music. Presently, he is music director of the Puget Sound Traditional Jazz Society, of which he has been a charter member since its founding in 1975.