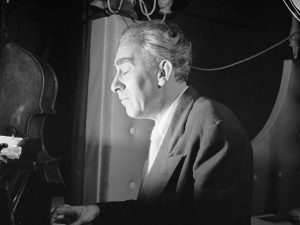

Pianist Ray Skjelbred is now in his 60th year as a professional jazzman. In this second of a two-part interview, he discusses the many people and experiences which have influenced his art, and how they have shaped his perspective on music and its performance. (Part One)

John Ochs: What is it about the music of Hines, Sullivan, and Stacy that inspires you?

Ray Skjelbred: Well, for me they are the big three, the Chicago guys that define piano as exploration, wild abandonment and beauty, like sort of the combination of madness and beauty, and no template, always seeming to create everything from the beginning each time. That’s how I love music.

With Earl Hines, there are so many things, like his mind never stops going with an endless supply of things that catch you by surprise. And he had big hands and could move tenths up and down the piano really fast, and then play a dazzling run, followed by a sudden stopping note with dead air for a fraction of a second, and then carry on with an endless supply of variation, and all of it creative and never showing off. It was all absolutely perfect every time.

Joe Sullivan was always thinking, “What am I going to do with this, now? I’m going to make something that’s never happened before, and it’s going to be passionate and powerful, and it’s going to be delicate, and it’s going to be out of its mind.” And that’s how Joe Sullivan played.

And Jess Stacy had these beautiful, wobbly tremolos that sounded to me like a human voice when he played. The most beautiful piano playing on earth.

There are a lot of other piano players I like, too. The list includes Thelonious Monk, Cass Simpson, Horace Henderson, Jimmy Yancey, Big Maceo, Sir Charles Thompson, Art Hodes, Roland Hanna, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Burt Bales, Zinky Cohn, Frank Melrose, and Mary Lou Williams. That’s quite a range of people. They don’t all play the same style, but what I love about each of them is that they are exploring and they’ve got a lot of deep blues feeling mixed in with what they play.

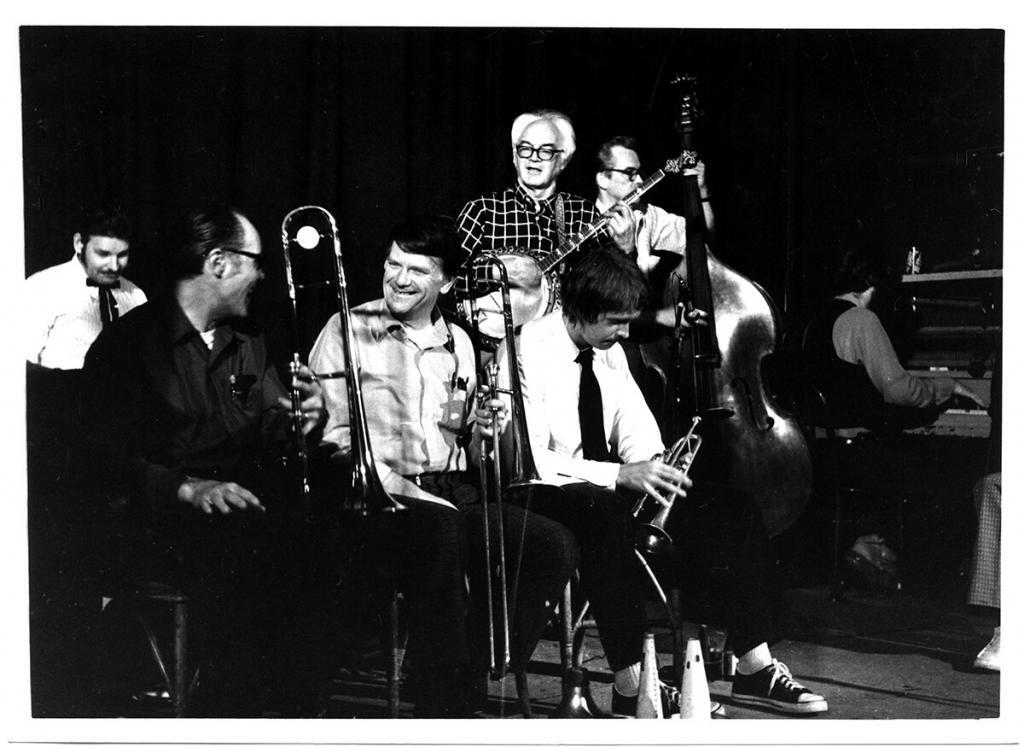

As far as jazz groups go, I think most of the great swing music happened before the swing era. I like the kind of dynamic swing where I can hear arranging and all the specific voices of the musicians. Some of my favorites are the orchestras of Jimmie Noone, Earl Hines, Red Allen, Spike Hughes, Horace Henderson, Billy Banks’ Rhythmakers, and Joe Sullivan at the Cafe Society. And traditional-jazz bands? I guess that would be early jazz styles that began to be rediscovered in the ’40s and on. My favorite would be the original Bob Mielke’s Bearcats band of the 1950s.

I love to play songs that are not piano songs. That was a big lesson to me listening to all of these players. That made a whole new world of material, playing what a band would do that no other piano player ever did. And with familiar material I often like to change the approach, like playing “Sleepy Time Down South” fast or “Pennies from Heaven” slowly. I also enjoy playing songs not usually associated with jazz like “I Dreamt I Dwelt in Marble Halls” from the movie Bohemian Girl or “The Alligator Pond Went Dry” by Victoria Spivey or a cowboy waltz like “Down the Lane to Happiness” or “Everyone Says I Love You” written for the Marx Brothers by my favorite composer Harry Ruby.

I like to think of myself as being influenced by horn players like Louis Armstrong or Red Allen on trumpet, or Frank Teschmacher or Jimmie Noone on clarinet, or Lawrence Brown or Dickie Wells on trombone. Or by singers like Maxine Sullivan, Ethel Waters, Lee Wiley, Victoria Spivey, and Connee Boswell, all of whom I admire for their lyrical passion. These musicians are all in my head when I play.

You have also written quite a few songs for solo piano. I’ve noticed from their titles that many have been written as tributes to piano players or other people you admire.

Yes, Johnny Wittwer told me that the title on the master of one of his recordings was scratched out with only a “C” at the beginning and a “t” at the end. The producer guessed it was “Canned Meat Rag” but it was really “Contentment Rag.” So later on I wrote a real “Canned Meat Rag.” I wrote a piece called “Don’t Crowd the Mushrooms” because that is what Julia Child said. I also have written several ragtime compositions that contain many hidden references to Thelonious Monk compositions.

Who are some other people who are recognized as important figures in jazz history that you have encountered in person or played with?

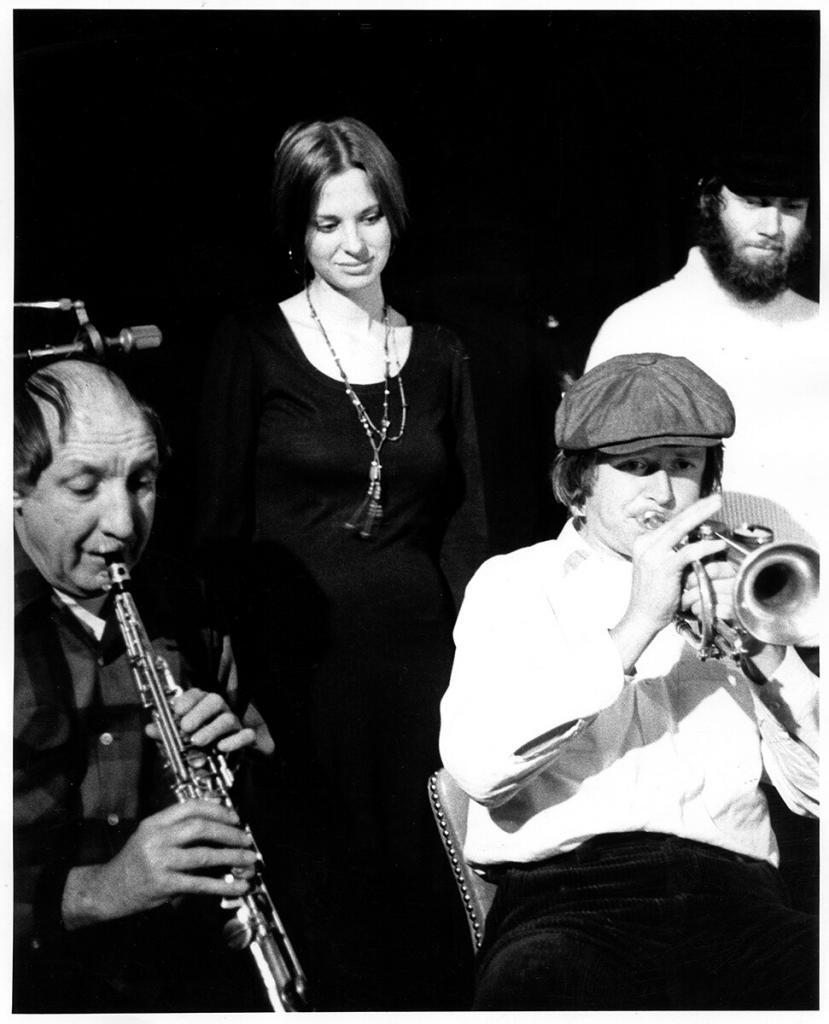

Well, I have very strong memories. The Bay Area people who I thought of as half a generation or more older than me were all wonderful, but if I thought of historical figures, maybe the one who stands out most was Darnell Howard, who went back to the earliest days of jazz, and he was a Chicago guy. He appears on all kinds of wonderful records.

He played on some of the most famous Jelly Roll Morton records and for about 10 years he played in Earl Hines’ big band in the ’30s, and then he played in Hines’ band at the Club Hangover in San Francisco, and I met him after that, but he was very sweet, very generous and we got together to play music several times, but we mostly just visited, and he was wonderful, a wonderful guy. I always thought Darnell had such a free and easy way of playing, such a passionate sound on his clarinet, and he was just a regular guy who sought out my friendship when I first met him. I don’t know, maybe he thought I looked like I was interested, and so one summer we spent almost every day together.

I know you also accompanied Victoria Spivey.

Victoria Spivey I met through the drummer Vince Hickey, who I guess somehow was related to her through marriage. I worked with her for several weeks at Earthquake McGoon’s, the Turk Murphy club, and I enjoyed that very much. She had really a great passionate voice, and she had been a big star since the 1920s. This of course was late in her life, but I know she was a strong spirit.

She called Dr. Hayakawa who was an old jazz fan friend of hers, but he was president of San Francisco State University at the time where I was going to school, and she wanted to know if I could be excused from school. I mean I was going to graduate school, and she was talking like I was in kindergarten so I could take her to the doctor during the day. She was a powerful figure. I loved the way she sang, and typically when she sang blues she would start with a kind of wordless moaning chorus and then go into the song, and she sang some popular songs as well as blues. I thought she had a great voice.

You’ve been recording both as a soloist and a band member since the early 1960s, and earlier this year you issued a solo collection on your own Orangapoid label. That’s approaching 60 years of recording. Do you have any favorites among all the recordings you have made?

I do have favorites but I hate to choose. I am especially proud of searching out interesting material and working with swinging, lyrical musicians. There are songs like “Dance of the Witch Hazels,” “Cavernism,” “KMH Drag,” and “I Dreamt I Dwelt in Marble Halls” that I am happy to have pulled into action.

The music scene in the Bay Area was extraordinary as far as the collegiality that existed between younger and older musicians. Do you have observations about that?

I’ve been both a younger musician and an older musician in the situation in which you either have been through it before or you’re just finding out about it. Fortunately, the older musicians when I was just beginning were very nice to me, maybe because they saw where I was trying to go with it. Dick Oxtot was very helpful to me when I first started playing, and I think musicians are always looking for sympathetic characters and people they can trust rather than just somebody trying to keep some kind of music going.

I’ve met a lot of younger musicians over the years. In very recent years, I’ve met sax player Jacob Zimmerman and some of his friends in Seattle. Earlier than that, I’d have to say Clint Baker is a younger musician to me and a wonderful one. I’m very happy I’ve sort of been able to be on both ends of history, and any time I was really playing music was a very rich and full time.

So I think it is important for younger musicians to learn from elders, but also for older musicians to learn from younger ones. Trumpet player Jack Minger was older than I was and I learned to play better and more accurate chords, melodies, and harmonies from him. Jacob is much younger than I am, and again, I have learned from him and expanded what I know about chords and songs. Both of them conveyed the inner working of a song more than any people I have ever known.

Over the years you have had some experience with radio both in Seattle and the Bay Area. In Seattle, it was with KRAB radio under the auspices of the community-radio pioneer Lorenzo Milam.

I believe that the jazz radio show Mike Duffy and I did together might have been the first steady, regular programming on KRAB. By that I mean you could count on it every week or whatever the plan was, and we did that for quite a long time.

How would you describe KRAB radio?

It was pretty free, and a lot of people were dedicated to the idea of it. Sometimes they were more dedicated to the idea of the station than they were to their technical ability to be able to run it. And there were times, you know, when the announcer microphone would be left on during a recording, or the music wouldn’t appear at all because it hadn’t been turned on. But that was kind of okay … little mistakes like that … but if you had a good idea, you could go somewhere with it on that station. I read several novels on the station, and I read short stories over the air as well as having the jazz show.

I also shared the Annals of Jazz show on KQED in San Francisco with Richard Hadlock for about 10 years, and then for a time I did some work in San Rafael. I can’t remember the numbers of the station now, but I got that through Jim Watt, who was another jazz radio person, and that was more complicated because that was the first time I had to run the station. I had to know how to push all the buttons, including one day I had to be the first one there and open the station, which was pretty scary, but I did it. I can’t remember the name of the station, but it was in San Rafael.

You retired from teaching in 2007. Maybe you could say something in general terms about your teaching career. What was your passion, what did you teach, what are you especially proud of?

Well, teaching is what I think of myself as most connected to, teaching and music and poetry. I taught a long time and I tried to teach in a way so that if I had more than one class which was supposed to be learning the same things that no two classes would be alike. And there were all sorts of patterns I could work out that would insure that there would be some kind of organic direction in the class that in many ways would be student directed, but I would still be guiding things in some way.

I loved teaching writing, and I loved teaching poetry. And I found that there were lots of very natural ways of connecting those things.

You’ve written liner notes about music as a tribal experience. I wonder if you think that method of transferring traditional jazz to the next generation is going to survive?

Well, I don’t … I don’t think it’s going to survive. I think you need more elders who have become elders by knowing elders before them who taught all the right things. I think that particular character quality is thinning out more and more, as are the circumstances for just playing, except at festivals which to a great extent are disappearing too. It’s kind of hard to say what the future is because there really isn’t any future at the moment for playing music, but to me that does seem like the way to do it.

When I started the very first playing I did in public was at a place called The Grove in Seattle, and Johnny Wittwer played piano there, and while I was taking lessons from him, I would go in there and he’d have me play a little bit, and then he’d talk to me about how I played later, and have advice. That was pretty special.

I say this from my own experience, but it seems to me you learn best from others either directly or indirectly, and you have to be really, really passionate about what you want to learn. It’s not just like a mild hobby. You have to be really involved in it or it won’t work. And I’m not sure the circumstances for that exist any more. I know there are jazz camps and people learn things but when part of what you learn is what clothes to wear and how to appear on the stage, those aren’t things that strike me as important. And I know there are good musicians coming along, but I think they’re very special people, and in the few rather than the many. So, I don’t feel real encouraged about that, but maybe there will be some other kind of music that takes its place, with instruments we’ve never heard of yet.

Your question reminds me of when the Great Excelsior band used to play at the University of Washington student center on Friday afternoons during the 1960s. I remember being interviewed by a campus radio person who asked me what I saw in the future, and I remember telling her that I did not see anything. There was no way that the way we played would ever be popular or lead to anything.

Maybe you could say something about the scene you’ve participated in since you’ve moved back to Seattle, such as the bands you’ve had and the musicians you’ve played with?

Since I’ve moved back to Seattle, there have been two worlds, one playing music locally and the other traveling. On the local scene, I lead a quartet featuring Steve Wright on trumpet and reeds, Mike Daugherty on drums, and Dave Brown on bass. We were called the First Thursday Band when we played once a month at the New Orleans Restaurant, and then we became the Yeti Chasers when we moved to the Royal Room. It’s the kind of band I like, a small group with a lot of room for wiggling around, and some arranging, but also a lot of freedom. And I also play for swing dancers with the wonderful clarinet and alto player, Jacob Zimmerman, and bassist Matt Weiner.

My traveling band is called the Cubs. In normal circumstances, most musicians I know usually travel a lot, but the Cubs band doesn’t travel very much right now because there isn’t anywhere to go due to the pandemic. It’s a really wonderful group. The highlight is Kim Cusack on clarinet, from Chicago, who helps define the whole Chicago style. The Cubs is really a Chicago-style band.

I also play in bands led by others both in Seattle and elsewhere. I’m grateful to all the smart, younger musicians I’ve gotten to know at all of these places, and I’m very proud of all those connections. I especially like to play with them, and I’ve learned a lot.

So, where do you go from here? By that I mean, since you came to Seattle you’ve recorded quite a few piano CDs, plus several small-group sessions. Do you have other things on your bucket list?

Oh, I always want to record more, but it seems like there isn’t much future in doing it. I think there are so many ways to hear music these days that the recording, as a recording, is dying. If you look at performances on the computer and YouTube, the one kind of music I have played that people are most interested in is on the dolceola. I look at a piano thing I did seven years ago, and 11 people have seen it, but I look at a dolceola thing and 30,000 people have seen that. I guess because it’s a novelty.

What is a dolceola?

The dolceola is a fretless zither, made between 1904 and 1907 in Toledo, Ohio. It has two octaves in the right hand that are like a piano and seven sets of chords in the left hand with various notes on each chord. The right and left hands are played differently even though they all look like black and white keys. In some ways it’s really hard to play because the keys are so small, and in other ways it’s easier because in the left hand there’s a triad for each of the seven chords so you can hit one key and get three notes at once.

It has a lovely sound, and I enjoy it a lot. It was supposedly played by Washington Phillips, the great Gospel singer. But in recent years a lot of people have recognized that the sound that he played is not the sound of the dolceola. He had some instrument that he sort of rigged up, and it was played differently. But the dolceola still is a wonderful sound, and I’m glad that people seem to like it.

So, after all is said and done, what’s your philosophy about music and music performance?

Well, I don’t think there is any one kind of music which is the right kind or that people ought to play. I am strongly moved by music that is passionate, personal, and a reflection of a talented person’s true self. In my own playing, I try to live according to never inventing some kind of musical sound that I’m trying to convince anyone else to like, but to do just whatever is my truest self and hope for the best, and go as far as I can that way, so I can feel good about what I tried to do. In some ways it doesn’t matter if I succeed at any kind of goal as long as the goal is the right one. But no show biz, although people have come up to me and said I was entertaining, and I guess they meant because I bounced around when I played. If that is entertainment, it’s okay, because it’s just a natural expression.

I like the best of jazz and other music that invents a world which may have a sense of experimentation, madness or sweetness. In addition to jazz I like, I would also include Charles Ives, the Sámi music, Norwegian fiddle music, Australian aborigine music, Tibetan horn music, Conlan Nancarrow’s piano-roll compositions, and old cowboy songs. I would rather not listen to traditional jazz if it lacks imagination, continuity, or individuality. I absorb from different directions.

But I am encouraged by the good traditional-jazz bands that do exist in the world. Maybe I think my Cubs group is wonderful, but so are the Fat Babies and the Grand Dominion Jazz Band and the Yerba Buena Stompers and Tuba Skinny and Jacob Zimmerman and his Pals. And they are all different from each other. And the music is art because of the inner character and direction of the performing musicians. The music survives not because it is a kind of music but because of who is playing it.

Visit Ray Skjelbred online at rayskjelbred.com.

John Ochs is a jazz fan and record collector who first met Ray Skjelbred at a Seattle Folklore Society concert in 1976. Since then, he has produced an LP, several CDs, and an award-winning film featuring Skjelbred’s music. Presently, he is music director of the Puget Sound Traditional Jazz Society, of which he has been a charter member since its founding in 1975.