Introduction

Recently written ragtime compositions, as a rule, do not attract much attention from the majority of ragtime aficionados nor the general public. However, as Max Morath stated both succinctly and humorously in his liner notes to his LP and CD versions of his 1973 recording, The World of Scott Joplin, to wit: “…as ragtime continues to establish its place in music there is a tendency to overemphasize him [Joplin]. (Astonishing to write that! For so many years, it has been Scott who?)…Both of us [i.e., Max and Rudi Blesh] feel that the classic ragtime form offers a fresh and challenging direction for composers today. The always-active Blesh has encouraged through recent publication and recording such gifted pianist-composers as William Bolcom, Donald Ashwander, William Albright, and Trebor Tichenor.”1

But let us now turn our attention to a decade before these words by Max Morath were written. What was available to the record-buying public in the genre of piano ragtime? Ostensibly, very little. There were a series of records released in the mid-1950s and early 1960s by the pseudonymous “Knuckles O’Toole.”2Rarely on these recordings does one hear anything resembling what one might recognize today as “ragtime.” They are mostly renditions of popular songs from the 1910s and 1920s (not that there’s anything wrong with that) played on a deliberately out-of-tune piano. Occasionally, one might find ragtime pieces from the initial era, such as Down Home Rag.3

On a personal level, I find many of these recordings to be not terribly interesting. I find the endless lack of change in dynamics, fake out-of-tune quality of the pianos, ricky-tick percussion accompaniment, and similar tempi between pieces to be unimaginative. Much the same could be said of many of the early recordings of both Bob Darch4 and Johnny Maddox.5 Regardless, these performers were at least putting pre-1960 popular music before the public at large and were getting noticed.

I suspect that the instrumental presentation possibly had more to do with the whims of producers than with the performers themselves. Even as late as 1979, when I did my first recording, I sat down to record one of my own rags, and was shocked at how out of tune the piano was. When I pointed this out to the recording engineer, he said something like, “Oh, but you’re playing ragtime, right? It’s out-of-tune honky-tonk stuff played in bordellos!” I quickly attempted to dispel this unfortunate notion, saying that the rags of Scott Joplin and others were to be equated with classical music, and that Joplin took his music extremely seriously. I was given a better piano which was perfectly in tune to make the recording, but I strongly suspect the engineer was very disappointed that I didn’t pound out a triple-forte, fast-as-you-can-play rendition of Twelfth Street Rag.

One other performer to release “commercial” recordings of “ragtime” was Lou Busch (Louis Ferdinand Busch, AKA Joe “Fingers” Carr). In terms of the recording industry, he had even greater visibility than Maddox or Darch, and composed a number of original rags of his own.6

There were some notable exceptions to the albums mentioned above, but these were getting precious little press. For instance, Lucky Roberts recorded some of his stride pieces for Rudi Blesh’s Circle Records (on 78 rpm shellac records) in 1946.7 Roberts, along with fellow stride pianist Willie “The Lion” Smith, recorded the classic, Luckey & The Lion: Harlem Piano, released by the Good Time Jazz label in 19608

And then there was Max Morath.9 In 1959, he created the first musical educational show for NET10 (National Educational Television ran from 1954 to 1970 and later turned into PBS).11 In these shows, while deftly talking about some of its origins, he used the platform not just to educate the public about ragtime, but about all popular music (and the culture which surrounded it) before jazz started to become popular in 1917. And even though he was given “out of tune” pianos to play on at times, his originality and musicality constantly shone through, as he brought together other musicians from the past and present as well. In my interview with him, Max stated that he became disenchanted with the recording companies with whom he was working in the 1960s. I suspect that it was because they were attempting to “pigeon-hole” him, and if ever there was a musician whom you can’t pigeon-hole it’s Max.

However, two things happened which completely changed both the general understanding and perception of ragtime, for those who were actually paying attention. The first was a book.

They All Played Ragtime (Book)

I’m not going to get into a discussion over the pros and cons of this book written by Harriet Janis and Rudi Blesh. But I do think that one can state unequivocally that it started the modern ragtime revival. All serious research on the subject begins with They All Played Ragtime, [Hereafter TAPR when referring to the book only] and there has never been any argument about that.

It was initially published in 1950. However, when it was republished in 1966, Blesh did something different. In an effort to bring the music itself more the public’s attention, he made sure that the scores of sixteen ragtime musical compositions were included in the center of the book. Many of these scores were given beautiful calligraphic work by contemporary ragtime composer Donald Ashwander.12 But people really needed to hear the music. And for that reason, around 1966, Rudi Blesh co-produced a long-playing vinyl recording to accompany the book.

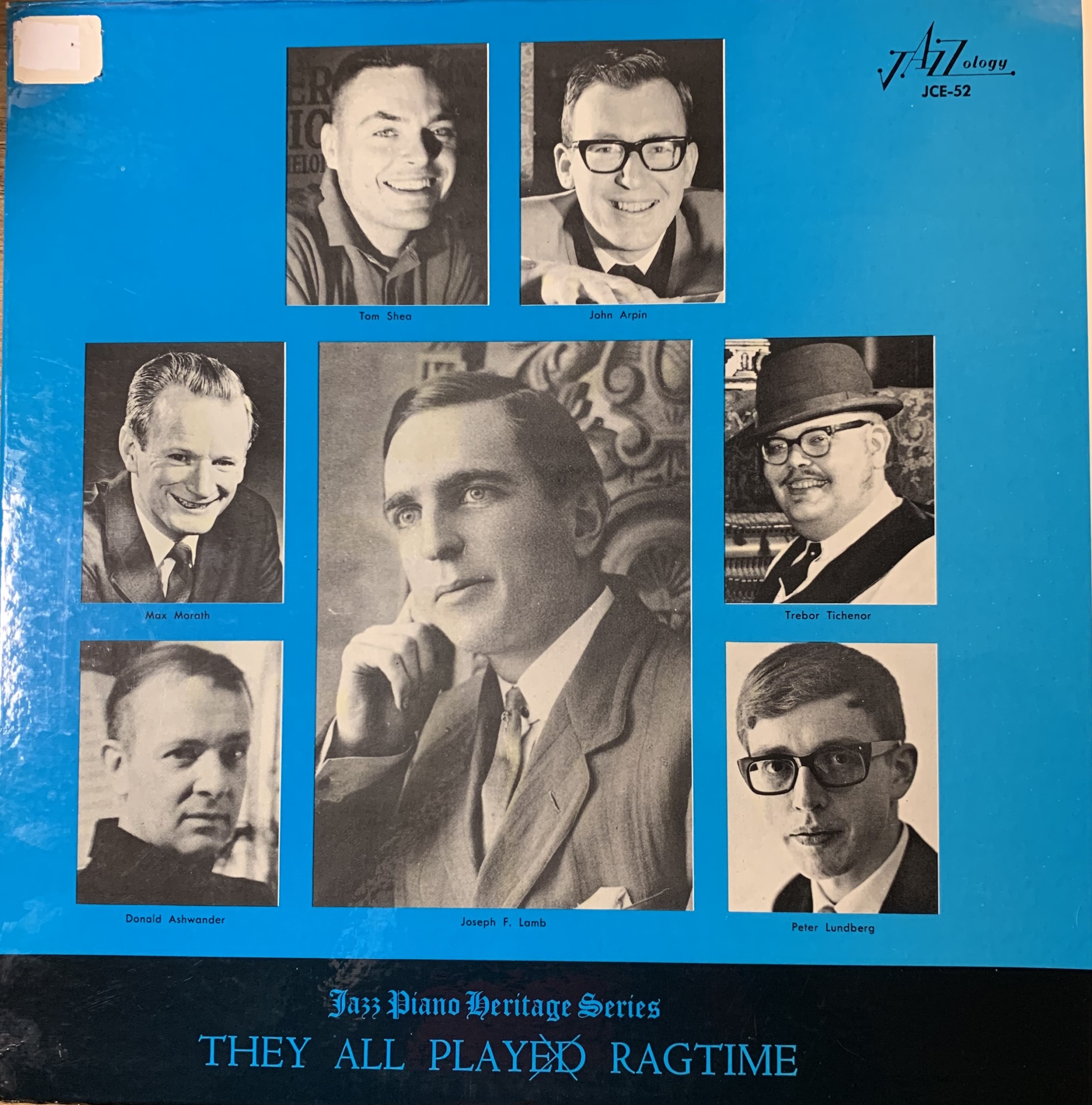

They All Play[ed] Ragtime (Record album)

In many ways, this album was unprecedented. It was an album of purportedly “popular” or “vernacular” music but was a non-commercial release. Not only that, but the release of this album was loosely coordinated with the aforementioned book to give readers of that book a better aural idea of the type of music being discussed within its pages. In these days of streaming and online purchase of mp3s at a dollar apiece, it is hard for people not alive at or near that time to fully comprehend how revolutionary this was.

In many ways, this album was unprecedented. It was an album of purportedly “popular” or “vernacular” music but was a non-commercial release. Not only that, but the release of this album was loosely coordinated with the aforementioned book to give readers of that book a better aural idea of the type of music being discussed within its pages. In these days of streaming and online purchase of mp3s at a dollar apiece, it is hard for people not alive at or near that time to fully comprehend how revolutionary this was.

It was released on the Jazzology label, owned by the late George Buck, with liner notes by Rudi Blesh, who produced it. There is no date of copyright anywhere to be found on the cover or label, but I believe it was released around 1966 or 1967. Peter Lundberg, who participated in the project, estimates this to be so, and that would make the most sense, seeing as it accompanied the 1966 edition of the book by Blesh and Janis (with all the scores).13

In addition to five tracks which were written by composers of the Scott Joplin tradition, there were seven tracks by five modern ragtime composer-performers of their rags all written after 1960, also written in a more serious mien.

Max Morath is herein represented by his two best-known works, One for Amelia, and The Golden Hours. The first is an homage to Joseph Lamb and named after Lamb’s widow, Amelia. The second was named by Rudi Blesh because all the time he worked on TAPR with co-author Janis were apparently golden hours. It is also the first ragtime piece to use polyrhythms (it goes back and forth between three and two beats to a bar).

On this album, Max plays them both at a much greater speed than on his 1973 Vanguard album, The World of Scott Joplin. And while the latter version is a more quiet, tender version with a greater awareness of a well-rounded piano sound, the 1966 recordings aren’t played exactly as written in the score, which is interesting, because he does so seven years later. It suggests that perhaps, in 1966, these two pieces had not fully gelled in his mind at that point.

The two works by Donald Ashwander, Friday Night and Business in Town, are, sadly, not accompanied by the stories which inspired them. While this doesn’t prevent one’s enjoyment of them, knowing the source of inspiration significantly adds depth to the experience of hearing them.

Friday Night was Donald’s first rag and it was presented to Rudi Blesh fairly shortly after its completion, and started their long friendship. As Rudi produced this album, it’s clear that he liked the piece, as it is presented here. It was completed on a Friday night. Business in Town was a musical reminiscence of a time when Donald was living on a farm in Alabama during the Great Depression, and his delight at being allowed to accompany his grandfather into town when he had “business in town.” Donald plays these works faster (and sometimes a little less accurately) than he would years later. And sadly, much of the its subtleties are lost in this recording, probably due in part to the speed of the performance and issues with recording quality, which I’ll delve into shortly.

From the increased speed of Donald’s and Max’s works, perhaps one might surmise that there was greater pressure to get the recording done? Or perhaps they were just young men at this time, and played faster then? One can only speculate.

Trebor Jay Tichenor’s effort here is Chestnut Valley Rag, and it is a rollicking, bucolic piece with, at times, a very heavy bass. It is clearly in the style of what Tichenor and Jasen refer to as “early ragtime” (or folk ragtime).

Tom Shea performs his own work, Brun Campbell Express, which has been played and recorded quite often, including at least three times by the composer.14 It is easy to understand its popularity, as it is imitative of a train, and has a lot of blues influences, such as the flatted third and seventh degree of the scale. Sadly, the recording quality of this piece is probably the worst on the album, as it sounds quite muffled, with a lot of tape hiss, and wavering volume levels. I suspect that the recording engineer did not set the recording levels high enough and did not clean the tape heads before recording.

Joseph Lamb also performs his own work, The Alaskan Rag, on this album. This is exactly the same performance issued on the Folkways album, Joseph Lamb – A Study in Classic Ragtime,15 released in 1960, the same year that Joseph Lamb died.16 While not exactly a virtuoso performance, it is still interesting to hear the composer from the Scott Joplin era, who actually knew Joplin, perform his own work. And what an extraordinary work it is.

Canadian virtuoso pianist John Arpin delightfully performs two previously unpublished “classic” ragtime works on this album, Silver Rocket by Arthur Marshall, and Pan-Am Rag by Tom Turpin, arranged by Marshall. Speculation has arisen regarding the authenticity of some of the earlier rags presented on this album and within the pages of TAPR book. However, with one exception, Peter Lundberg (whom we shall meet shortly) and ragtime historian and Renaissance Man Galen Wilkes assure me that all except one are certainly the “genuine article.” Most of the rags appeared in Marshall’s handwriting, so we can be assured of the provenance at least to that point. Sadly, almost all of Marshall’s original manuscripts were sold to private collectors after the death of Rudi Blesh (who owned most of them).17 Pan-Am Rag is currently held by the Library of Congress.18

The most “suspicious” work (which does not appear in this recording, only in the book, TAPR), is Pear Blossoms which is attributed to Scott Hayden and “Arranged by Bob Darch.” From my analytical perspective, the style of this work seems completely incongruous to every published Hayden work with which I am familiar. In the rags published with Scott Joplin, Hayden’s style is full of rapid sixteenth-note right hand work. Not so in Pear Blossoms, it is mostly made up large clumping chords in the right hand. In Hayden’s style, we sometimes find chords, but they are usually just small thirds, and occasionally there are octaves which are used for syncopations.

Also, in the second bar of the first strain, there is a misspelled “German 6th” chord, and in bar two of the last section, there is a IV ♭7 chord. These harmonies were almost never used by composers in the Joplin Tradition of ragtime composition, and most certainly were never used in any of Hayden’s previously known or published works. In addition, we see chromatic movement in an inner voice in the right-hand part of measure 14 of the second strain. We might see this type of technique used in the Novelty Rags of Zez Confrey, but it is completely out of character for this style of early or classic ragtime.

For the above reasons, I’m going to “stick my neck out” and speculate that that rag in the TAPR book was probably written by Bob Darch who tried to convince others that it was only his arrangement. This makes the most sense to me.

Peter Lundberg disagrees with me about this. About the controversy, Peter states, “Calliope Rag to me is plausible [as] a Scott unfinished piece with additions by Bob [Darch]. I think you would agree that Scott is the most pianistic writer – demanding, but never awkward to [the] hands. The first strain of [Scott’s rag] Hilarity Rag lets you keep your hand almost still through the descending chord figure. It resembles the first strain of Calliope Rag. And the trio has the subdued march writing of the trio in Evergreen Rag. So, I would go for [the rag as being by] James Scott, unfinished, with Darch additions…[regarding] Pear Blossoms…in Bob’s recording [of] it, [it] is a fine early style rag and I can believe it is basically a Hayden piece.”19

Ragtime historian Galen Wilkes provided the following to me regarding the rags in TAPR (book): “Most of the scores are [truly written] by the composers. [Arthur] Marshall’s scores are his, [and] the [manuscripts] exist. Turpin’s Pan-Am Rag is his. The arrangement was by Marshall and that [manuscript] exists as well. The [James] Scott rag, Calliope, was an incomplete piece in [manuscript format, and] given to Bob Darch by a Scott family member, which he completed along with Haven Gillespie.

“Another work, Pear Blossoms, [purportedly composed] by Scott Hayden, Bob [Darch] claimed to have completed as well. I’ve never heard anything in [that] piece that sounded like Hayden. I’ve always dismissed it as one of Bob’s efforts to forge a period work. With Hayden being a [favourite] of mine, I was greatly disappointed when I heard that work and wondered how [Hayden could] ever [have written] it.”20

On this album, Donald Ashwander also plays James Scott’s Calliope Rag (mentioned above), and Max plays the then-recent discovery of Marshall’s Missouri Romp. While we can hear numerous other recordings of Max playing works not his own, this album provides the only known recording of Donald playing a work by an early ragtime composer (or any composer other than himself). It is interesting to hear Donald’s distinctive playing style adapted to James Scott’s work.

I’ve left the most unusual until last. Peter Lundburg’s Gothenburg Rag also appears on this album (its only “commercial” release, to my knowledge). It is quite unique, and very stylistically different from the others (although I disagree with Blesh’s assertion that it might owe something to Grieg).21 In my opinion, to produce a work of such maturity at such a tender age made Peter an extremely talented young man.

I asked Peter how he came to know Blesh: “…I met Blesh on my first visit to the US. In early 1963 I travelled for three months by Greyhound (99 days/99 dollars) around the country…to seek out old ragtime…and jazz people, and of course younger fans like myself…The whole trip is described in a lecture I did at one of the Blind Boone festivals…commission[ed] from the festival’s organizer, Lucille Salerno. The Syncopated Times…recently [printed] this together with comments and some photos…I called Blesh who was nice enough to take me around a bit and we stayed in touch.”22

I presumed that because of the publication of Gothenburg Rag in the TAPR book, for that reason Peter became involved with the record as well: “I got a letter out of the blue and of course consented. If [the album] was [made in] 1966, then I was 24, but I am not sure of the date. The piece was written in 1966 for the new edition of the book…I [liked Rudi’s] enthusiasm…I visited him in his office (one when Max Morath also was there) and his including me in the book [TAPR], and presenting me with copies of other writings made me favorable towards him. For some reason, I have a mental…[image]…of Blesh at a play[er] piano, pumping away at a piano roll of James P Johnson’s…Eccentricity.”23

To Peter’s memory, the album came out very shortly after the book: “…[I] assume it [the album] was [released in] 1967. I asked a local pianist, [an] orchestra conductor and bandleader, who recorded me at a studio in his home.24 I remember playing in his elegant sitting room while he was recording downstairs…red light bulb and all that. He had a good-sized grand piano. The recording sound[s] a bit subdued and I have no idea why. Also, my playing is a bit subdued. At the time, the idea of ‘Classic Ragtime’ was spreading and I probably leaned towards the semi classical direction. [There was] no editing! You can hear in the interlude and trio I have moments of hesitation, but we went over it a couple of times and chose the best take. Reel-to-reel [tape is] what [we] used, and I sent the original to Blesh.”25

During Peter’s initial trip to the U.S., he got to know many people, including Trebor Tichenor (who held a party for him and Peter’s mother in 1963) and Max Morath, of whom Peter writes, “I…also met Max Morath on my trip and had dinner at his home. We corresponded slightly and Max sent me tape copies of his TV programme and scripts from them. I later became director/producer with the Swedish Broadcasting [company] and I had a lot of inspiration from Max’s work. He was a pioneer in the television medium…[In addition], Max issued a sheet music album, a ‘Guide to Ragtime’ with some contemporary compositions, and he asked me to send one to include. So, I wrote another rag (which my mother liked and so I dedicated it to her) [entitled], Hippocampus Two-Step”.26

Peter made only one other recording but was not happy with it, and it was not released. He did, however, play in Sedalia in 1973, the year before the first Scott Joplin Festival, and toured very briefly with Bob Darch. About the experience of the record album, he writes, “It was just such an honor to be included. I could wonder why they did not try to get Bob Darch to [record] Calliope Rag. That piece is probably more Bob than Scott although I am sure that Bob [possibly] got some kind of sketch from the Scott family. Or better, why not include Bob doing his [own] Opera House Rag? …[the score of which was included in the book, but there was no recording in the album]…But I know nothing of the production.”

I, too, am confused why the album did not include Bob Darch playing his Opera House Rag for the album. I’ve played the work myself, and it is a fine piece. Peter highlights the tragedy of Bob not being involved in the project: “…Bob had a personality and he had honed his craft, tried out stories, checked audience reactions and he was a live performer. He was never a scholar though more widely read than you would expect. His cultural interests were wide, but his public figure was about his passion for ragtime. Tall stories abounded but…many of them were [true]…his piano lessons started with a relative of Tom Turpin, he met Percy Wenrich and other[s] from [the original ragtime] era. Then ragtime changed from entertainment to concert music at festivals and maybe Bob Darch became a survivor of an earlier age and many who met him casually saw only the heavily drinking old man and his jokes and stories. But for a long time he was a centerpiece of the Sedalia festival [Scott Joplin Ragtime Festival], with his motto, ‘Ragtime dead? Hell, it ain’t even sick!’ And in the very few examples of his playing when at his best, there is a sound, and beat, that is more authentic than most of us can accomplish.”27

Regarding the historical status of the album, Peter relates the following: “I don’t think I ever heard anyone mentioning the album. But [on] one occasion someone mentioned Gothenburg Rag and someone else said, ‘A classic!’ That surprised me. There is also at least one video of somebody else [playing Gothenburg Rag]…and of course I am pleased without bounds for that.”

As to the lack of commercial success of the album as a whole entity, there are myriad reasons. The first is, of course, is that it was not intended as a commercial venture, but rather as an important form of musical documentation.28 The second is that when this album was released (around 1967), as Max Morath related in his interview with me, the recording industry was controlled by a small number of behemoth labels, and if you couldn’t record with them, then you got next to no distribution. This album would not have been distributed widely at all. Thirdly, despite the importance and competence of the compositions and the performers, there are, at times, some severe technical defects of both the recording of the tracks, and the record itself. Fourthly, what may have killed this album for a lot of listeners was the fact that it was released in MONO (or one-channel) format. This would have presented no great challenge to a connoisseur like Rudi Blesh, who cut his producing teeth on the mono 78 rpm records of the likes of Luckey Roberts. But for most of the record buying public and audiophiles alike, Stereophonic records had been a mainstay since 1958.29 Fifth, there is barely a total of 30 minutes worth of music on the entire album, which is parsimonious even by the standards of the time.

Finally, there are no timings listed on the album as to how long the tracks were, and without timings, you could get no airtime on the radio, which was all-important for the sales of albums at that time. These technical considerations to producing an album are imperative to it being able to sell any copies at all, and it is unfortunately apparent that both Rudi Blesh and George Buck “dropped the ball,” in this respect.

Regardless, this is an absolutely essential and necessary album to the history of ragtime, for it presents for the first time, in non-commercial format, mostly competently-recorded, professionally played rags, both modern and old, with great diversity of both compositional and playing styles, and gives us some of our earliest impressions of the major players of that time. Ragtime and musical history would be bereft without this document.

Finally, this being a first was something that Donald Ashwander pointed out to me. He then stated to me that he considered my Graceful Ghost: Contemporary Piano Rags album to be the most diverse album since They All Play[ed] Ragtime. Not only that, but The Graceful Ghost was also the first album consisting completely of post-1960 ragtime in anthology format ever released (originally in 1994 and re-released in 2007). But had it not been for this Jazzology album, mine would have been much harder to get anyone to take seriously.30 My album was fortunate enough to have a precedent. A precedent always enables something else to happen. Keep this in mind: They All Play[ed] Ragtime had no precedent.

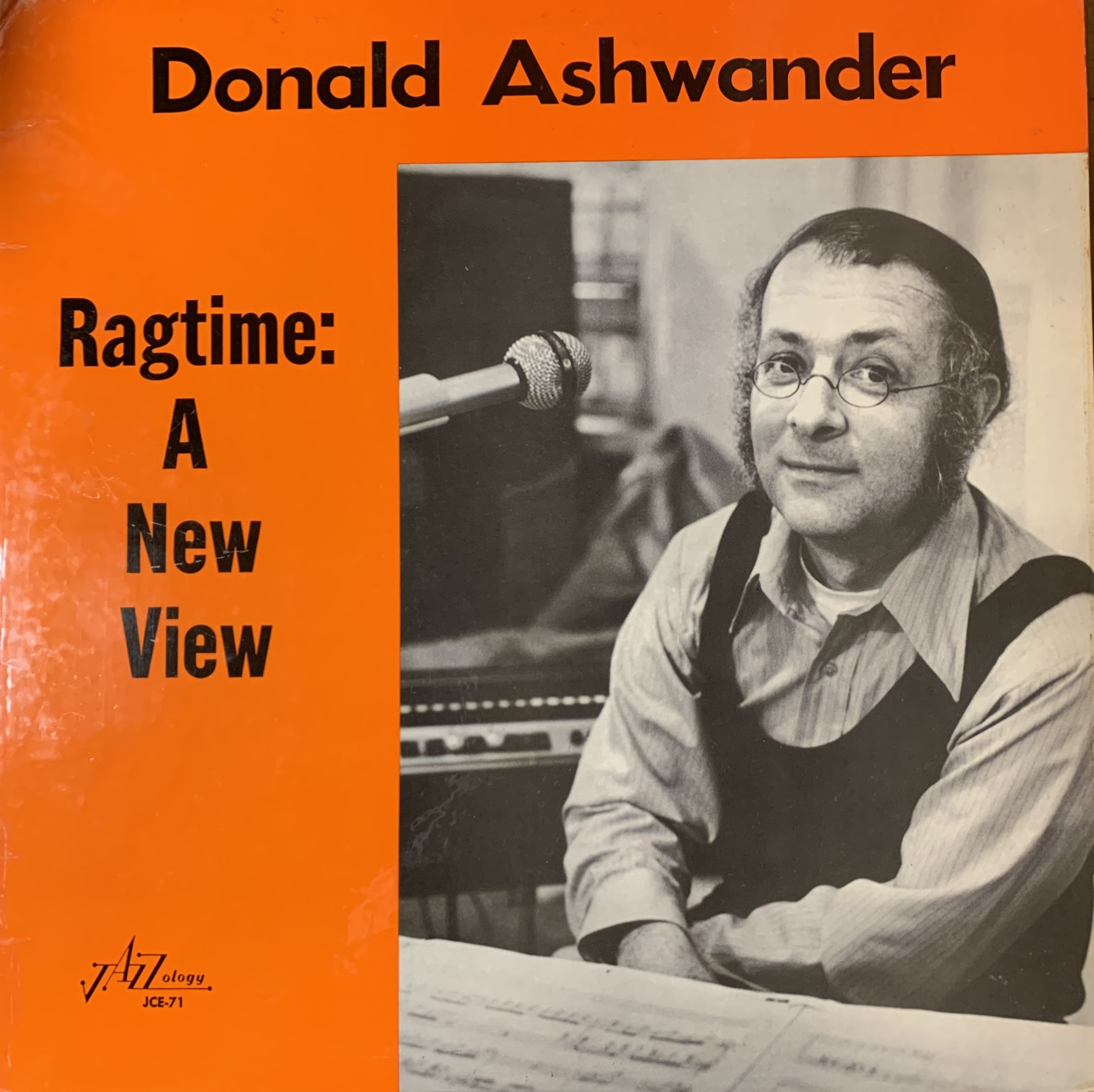

Donald Ashwander: Ragtime – A New View

This vinyl LP album was also produced by Rudi Blesh and released through George Buck’s Jazzology label. Similar to its relative above, it also shares some of the same production flaws (e.g., no timings given for the works, the recording is completely in MONO format, with a lot of tape hiss indicating that recording levels were probably not set high enough by the recording engineer, and a lack of distribution due to it not being made by one of the three or four largest record labels, etc.). Another serious issue is that the stories behind his rags are of phenomenal importance to one’s appreciation of the music. Blesh does not give Donald any room in the written liner notes on the cover to discuss the inspiration or explanations behind the composition of his very uniquely styled rags.

This vinyl LP album was also produced by Rudi Blesh and released through George Buck’s Jazzology label. Similar to its relative above, it also shares some of the same production flaws (e.g., no timings given for the works, the recording is completely in MONO format, with a lot of tape hiss indicating that recording levels were probably not set high enough by the recording engineer, and a lack of distribution due to it not being made by one of the three or four largest record labels, etc.). Another serious issue is that the stories behind his rags are of phenomenal importance to one’s appreciation of the music. Blesh does not give Donald any room in the written liner notes on the cover to discuss the inspiration or explanations behind the composition of his very uniquely styled rags.

However, this album does have some advantages over the previous album. For one, only one piano was used throughout, giving it a consistency of sound absent from the prior effort (not that that could have been avoided, however); and there is also a consistency of musical voice as all the works are written and played by one composer-pianist.

Like the previous album, Jazzology does not provide any copyright nor dating information on the record label, nor cover. This obviously presents a challenge when trying to figure out when it was released. I’m guessing probably around 1969 (when Empty Porches was composed) or 1970.

I’ve listened to this album many times, and knowing Donald and his work as well as I did, I’m going to be frank: having heard Donald’s later work, I felt disappointed. In my opinion, it is not, perhaps, Donald’s best work. Of all the twelve pieces on both sides of this record, only four of them stick out in my mind: Empty Porches, Mobile Carnival Rag Tango, Astor Place Rag Waltz, and Peacock Colors. I believe these to be unmitigated ragtime and rag-waltz masterpieces. This is, no doubt, the reason why both Donald and I recorded them around 1989 and 1998 respectively. Actually, I recorded Empty Porches in 1993 and it was released on the first Graceful Ghost album the following year and re-released on my album of Donald’s work in 2000.

I strongly suspect that Donald would have agreed with me. He only once mentioned this album to me, but was more evidently pleased with the two albums he recorded in 1979 and 1989. Donald had very exacting standards, and I suspect that, overall, he was not satisfied with Ragtime: A New View (this opinion is also based on recent discussions I’ve had with people who knew Donald as well).

Of the other works on this album, all of them show Donald’s distinctive jaunty style, and perhaps one of the most melodious is the first on side one, The Ragtime Pierrot. But to a large extent, despite the fact that Donald uses a wide range of key and time signatures, and shows mastery of many rhythmic and compositional devices, my opinion is that most of the pieces herein use many of these same devices which Donald was to use to much greater effect in his later ragtime compositions. I suspect that’s why he never recorded the other eight pieces ever again, nor ever sent me scores for such.

But on the more positive side, to have one-third of your first record album made up of exceptional, masterful works of which anyone should be proud, is, in itself, a rare accomplishment. It contains almost 50 minutes of music, which displays a body of work. And it is a rare opportunity to hear Donald as a very young man (at approximately 30 years old), showing a very rare and distinctive gift.

Empty Porches is a musical depiction of how front porches in the south were no longer where people congregated during the summer, but were now replaced by the steady hum of air conditioners and the flickering lights of television sets. It is a heartbreakingly beautiful work, and is more akin to “picture music” rather than “programme music,” the kind of approach made by Maurice Ravel (it is not without reason that Rudi Blesh evokes Ravel’s name in his own liner notes). Mobile Carnival Rag Tango also evokes a picturesque musical scene of Mobile’s annual Carnival, and the piece changes moods and compositional devices often. Astor Place and Peacock Colors are two rag-waltzes, and both reflect the syncopated waltz approach of Scott Joplin, but are thoroughly modern in their use of harmony, rhythms, and musical phrasing.

In my opinion, one of the most interesting thing about this album is how he often uses extremely exaggerated rubato in his playing of his own works. This had never been done before in any ragtime recording to the best of my knowledge (Max Morath would do so to even greater effect in his 1973 Vanguard album, The World of Scott Joplin). Rudi Blesh even points this out on the cover liner notes. Finally, I believe this to be the first complete record album consisting solely of a single modern (or possibly any!) ragtime composer-pianist.

This album does show significant promise. Fortunately, Donald kept composing and recording, and when he released his first Sunshine and Shadow album (on Upstairs Records in 1979), and then recorded his ill-fated On The Highwire album in 1989,31 we can see the extraordinary fruits of his labors: one of the greatest ragtime composers who ever lived, using stunning chord progressions, bass lines, and unusual compositional devices to produce a very distinctive, southern-folk-music-influenced style of contemporary ragtime.

And like They All Play[ed] Ragtime, there was no precedent for this record.

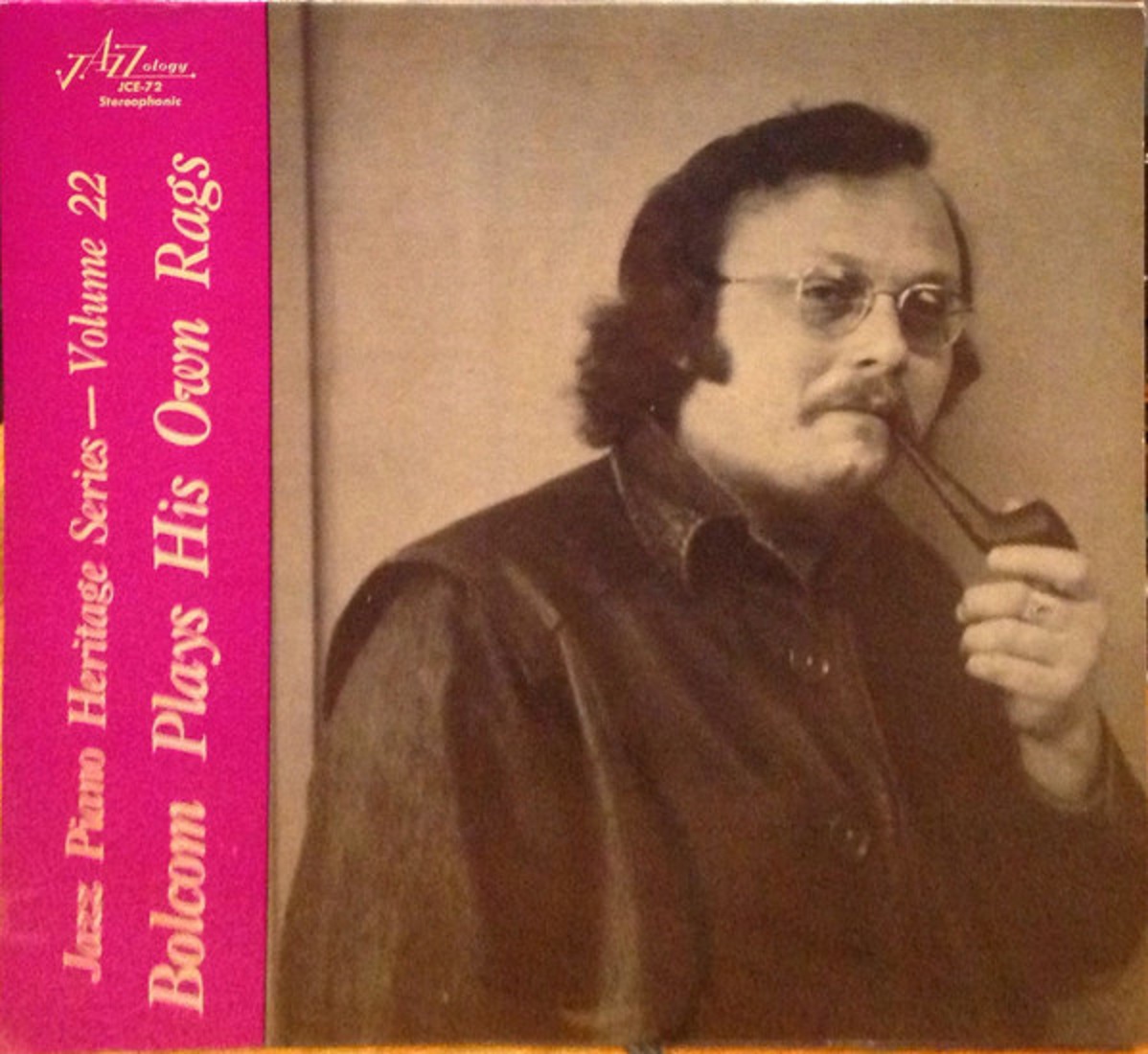

Bolcom Plays his own Rags – William Bolcom

From a technical perspective, this album is considerably smoother and more adept than the previous two. There are some technical flaws, for instance, there is quite a bit of “tape hiss” which can be distracting at times. At the beginnings of each side there is also some “pre-echo” or “print-through” which is quite noticeable. This happens when the recording engineer stores the tape with the beginning of the tape facing out of the reel. The magnetic information literally “bleeds” through the tape, so you can hear a little of the beginning of the recorded part of the tape on the opening grooves of the record just before the music truly starts. Clearly the mastering engineer did not store the tape with the “end out” of the reel.32 Once again, there does not appear to be any copyright information anywhere on the record label or cover, so it is difficult to date. But I believe it to be about 1971 or 1972 for reasons I will reveal later on. And, like the other Jazzology albums, there are no timings for any of the tracks, which means that the pieces did not have much chance to heard beyond the record itself (i.e., no radio or “air” time).

From a technical perspective, this album is considerably smoother and more adept than the previous two. There are some technical flaws, for instance, there is quite a bit of “tape hiss” which can be distracting at times. At the beginnings of each side there is also some “pre-echo” or “print-through” which is quite noticeable. This happens when the recording engineer stores the tape with the beginning of the tape facing out of the reel. The magnetic information literally “bleeds” through the tape, so you can hear a little of the beginning of the recorded part of the tape on the opening grooves of the record just before the music truly starts. Clearly the mastering engineer did not store the tape with the “end out” of the reel.32 Once again, there does not appear to be any copyright information anywhere on the record label or cover, so it is difficult to date. But I believe it to be about 1971 or 1972 for reasons I will reveal later on. And, like the other Jazzology albums, there are no timings for any of the tracks, which means that the pieces did not have much chance to heard beyond the record itself (i.e., no radio or “air” time).

On the positive side, because there were precedents to this album (i.e., the above Jazzology albums, and the fact that Bill made a stellar record for the Nonesuch label shortly before this one), not surprisingly, I believe this to be, in many respects, the most technically accomplished effort so far. It is recorded in stereo, and the musical layout of the album shows great understanding of the need for musical diversity within an album, even of a style of music as structurally well-defined as ragtime. And there is over fifty minutes worth of music, once again presenting a body of work within the record as whole.

The first on the album is Glad Rag, which apparently was Bill’s first rag written after he became acquainted with the score of Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha. It elegantly slides back and forth between gestures found in “Classic Ragtime” (in E♭) then there is an unusual harmonic move to D major where one hears elements of Novelty ragtime, followed by a move back to the “Joplin” style at the beginning. The juxtapositioning of two seemingly incongruous styles is cleverly done and shows great maturity for a first ragtime piece.

Secondly, we hear one of two of Bill’s rags influenced by the Classic Ragtime master, Louis Chauvin (the other is the more celebrated Graceful Ghost Rag). Epitaph for Louis Chauvin cleverly uses a rhythmic device which Jasen & Tichenor refer to as the “Scotch Snap” and which appears as a throw-away in the last four bars of the second section of Chauvin’s only rag, Heliotrope Bouquet.33 Instead of it being a quick ending, Bill develops the idea into an entire first section of the rag, which I think is quite ingenious. He uses fairly simplistic harmonies at first, but where there are repetitions, Bill modifies the harmonies a little, much as Brahms did in his piano works (despite the fact that the piece owes more to French harmony than German).

Tabby Cat Walk follows, and it is light-hearted frolic. It is quite playfully chromatic and is perhaps unintentionally influenced by the use of silence one finds in the work of Anton Webern, the silences are used to great comic effect at the end, so that the listener is never quite sure where the piece ends.

Another is stand-out is Last Rag which was Bill’s attempt to “kick the habit” of writing rags, which fortunately, he was not able to do. This is the only one on this record which I personally have performed, so I know that while it may sound easy to play, there is actually a lot of sophistication and use of inner voices, making it quite difficult to play well.

In the liner notes Rudi Blesh states that Bill’s Garden of Eden: Rag Suite from 1969 is probably the first rag suite, but I would debate that, as William Albright wrote Grand Sonata in Rag the previous year, and while the latter is not exactly a suite, it is the first attempt, I believe, to use ragtime piano materials on a grand scale. Of the four pieces in Eden, I would choose the last, Through Eden’s Gates as my favorite. It was also recorded by Max Morath in his Vanguard album, The World of Scott Joplin, Volume 2. I believe that that is the only rag by a contemporary ragtime composer other than Max to have been recorded by Max, so that should surely speak to its quality.

Lost Lady is also very impactful with its Chopinesque quality. It is largely written in a major key and fascinates in how it ends on the chord of the relative minor of the opening key. There are little adornments to the melodies as they repeat. And finally, there is California Porcupine, which I believe owes something in its use of repetitions and bass patterns to those which Eubie Blake employed, but done in a more contemporary way.

I have listened to this record many times as I have with the others. I think it certainly helped that Bill had the Jazzology precedents which enabled him to make such an artistically successful album. However, Bill was at a very different stage in his life and career than Donald was when Donald’s album was made, so one shouldn’t judge Donald’s album too harshly.

Keep in mind that Bill was a child prodigy who studied with some of the finest teachers in the world, and that he had studied a large amount of “classical” repertoire, so that when ragtime came along, he was ready to ensnare it and make it completely his own at this time in his life. He was also fortunate enough to have already recorded a stellar and well-respected album of ragtime pieces for the Nonesuch label, entitled, Heliotrope Bouquet. Having such a wonderful producer as Teresa Sterne34 to assist him in putting together his Nonesuch album could only have helped to hone his sensibilities to produce this, an album which, while being arguably just “parts,” is also the extraordinary sum of its parts. The individual rags are not just the only compositions: this album as a whole, because of the quality, selection, and arrangement of the rags, becomes a composition in and of itself.

All of the above experiences gave Bill the expertise to be able to produce, what I believe, was an accomplishment heretofore unachieved: a diverse selection of original modern ragtime pieces by the same composer-performer, cleverly arranged so that the album itself is a work of art and not just a dry catalogue, and performed cleanly as a concert-trained classical pianist.

In the cover liner notes, Bill makes reference to his colleague William Albright, whom he states is “…writing wild rags.” And this leads us to our final album examined in this effort.

Albright Plays Albright

This is the only album examined herein which was not released by Jazzology, and was also not released until some years after it was recorded. From an audiophile standpoint, all the boxes are checked: it is in stereo, no tape hiss that I could detect (which means that the recording levels were good); no “print-through”; while there is a little natural reverb, it is not overwhelming; there are timings indicated for every track so we have an idea of how long each piece is; both the recording and mastering engineers are credited; and there are good liner notes written by the composer himself which lets us know something about the nature of the music itself, according to and directly from the composer.

This is the only album examined herein which was not released by Jazzology, and was also not released until some years after it was recorded. From an audiophile standpoint, all the boxes are checked: it is in stereo, no tape hiss that I could detect (which means that the recording levels were good); no “print-through”; while there is a little natural reverb, it is not overwhelming; there are timings indicated for every track so we have an idea of how long each piece is; both the recording and mastering engineers are credited; and there are good liner notes written by the composer himself which lets us know something about the nature of the music itself, according to and directly from the composer.

It does not state on what kind of piano it was recorded, but it sounds to me like it was quite possibly a Steinway. There is also no indication of the recording location other than it was in “Ann Arbor, Michigan” which I suspect means it was probably recorded somewhere at the music school at the University of Michigan.

While I don’t know for sure, I speculate that Albright, like I so often did, possibly recorded this album “on spec” (that is, without a releasing company in mind). I believe this for several reasons: one is the large amount of time between the year of the recording (1973) and its eventual release (1980) by which time, analog recording was starting to wane, and musicians like Paul Jacobs were just starting to record using digital technology. Also, Albright gives a contact address on the album which I discovered was actually his home address at the time of the album’s release.35 His biography on the album mentions that he had recently received grants from the Guggenheim foundation and the National Foundation for the Arts, so it is possible that he might have paid for the recording himself, and used grant money to pay for its eventual release.

In addition, Albright was to release this album through Musical Heritage Society, which like many book clubs of the time, largely sold records on a subscription basis, quite often from the licensing and reissuing of albums released by other companies.36 This was no indication of poor quality; this label released a number of excellent albums over several decades. But it was, apparently, unusual at this time for Musical Heritage Society to directly release albums itself.

Further, it neither mentions nor infers the name of a producer, and Albright is credited with the art work for the cover, which means he probably had a hand in the design of the cover layout himself (as I did for many of my albums).

As stated before, Bill Bolcom referred in his album to Albright’s “wild rags.” While that is true for much of this record, both sides of this record start with rather conventional offerings: On The Lamb (side one) has a few modern twists and turns (such as chromaticism unusual to ragtime of an earlier style) but is largely in the traditional Joplin vein of composition and is dedicated to Bill Bolcom (just like Bill Bolcom dedicated his first rag, Glad Rag, to William Albright). Onion Skin Rag (side two) operates on the same level.

However, as soon as we get into the second track of side one, we start hearing some very innovative ragtime pieces, indeed. Burnt Fingers is modeled after the Novelty Ragtime of the 1920s, but goes many steps further in its use of chromaticism and unusual harmonic sequences. Sleight of Hand is probably my second favorite on this album. I noticed some years before I read Albright’s notes on this album that one of the last sections of the rag is somewhat reminiscent of (Second Viennese School composer) Anton Webern’s use of parsimonious pointillism. The first time through, you only hear snatches of melodic fragments. The second time through this section you hear what the music sounds like without having chunks of music “cut out” and replaced by silence. The effect is at first confusing, then exhilarating. Having played it myself, I think I played it quite a bit slower than Albright does here. Personally, I prefer Albright’s interpretation to my own. This rag is startlingly innovative on many levels, and I believe it to be the first example of pointillism used in tonal music. Further, Albright did it a good six years before Frederic Rzewski used the same device in a similar fashion in his piano work, The People United Will Never Be Defeated.

My favorite track on this album is undoubtedly The Sleepwalker’s Shuffle, part one of a three-part suite entitled The Dream Rags. I’ve played and recorded this one myself as well. While Albright’s rendition is obviously excellent in all respects, I personally prefer it at a much slower tempo. My colleague, Gary Smart, has also played this rag very well indeed, and I have to say that I prefer this piece played at the much slower tempo at which Gary and I have played it. Nonetheless, it is still an enthralling and deeply innovative work in its use of harmony and major contrasts of dynamics.

This is the first ragtime album which truly pushes the envelope in trying to extend the ragtime form as far as humanly possible. In the first movement of the three-movement Grand Sonata in Rag, entitled, Scott Joplin’s Victory, I hear Albright trying to use ragtime materials in a manner more like that of a first-movement form of a sonata. Personally, I’m not sure that it works. For me, the charming simplicity of the ragtime form is its use of four contrasting and occasionally repeating sections, usually each lasting around 16 bars. Sonata form is completely different from the structure of a classic piano rag, and for me, many of the ideas don’t seem to coalesce nor compliment one another.

I also noticed on occasion that Albright appears to be “stealing from himself.” For example, at the 1 minute 30 second mark of the last track, Morning Reveries, I hear a sequence that sounds startlingly similar to the interlude between the second and third sections of his rag, Sweet Sixteenths (which does not appear on this album).

The only other qualm I have about this album is Albrights’s occasional use of the compositional device of octave tremolos in the right hand. I tend to side with Glenn Gould in thinking that this device sounds a little bit too much like “Granny at the Parlor Upright.” But these are comparatively minor quibbles.

More successful, I believe, is the second movement of The Dream Rags, entitled, Nightmare Fantasy Rag – A Night on Rag Mountain. I strongly suspect that the traditionalists (or those to whom I refer as, “Ragtime Fundamentalists”) would probably not like this piece, because it extends the rag form so much, and lasts almost nine minutes and thirty seconds (most rags tend to last around two to three minutes). Part of why I think this works better than Scott Joplin’s Victory, is that it remains truer to the traditional rag structure, and does not try to combine it with other forms. I also believe its use of rag devices to be more inventive.

For instance, after a slow introduction, we hear a chromatic “walking bass” in the left hand. Personally, I would never use such a device for fear that someone might say, “Oh, Eubie Blake did that in the first section of the Charleston Rag!”. But Albright somehow gets away with it. Upon closer inspection, one can hear that Albright inverts the left hand walking bass pattern which Blake used by having the lower note played by the fifth finger being accented and the note above play afterwards leading to the next down the scale. This is the opposite of what the left hand does in the Charleston Rag. And then, in the right hand after we hear the walking bass, we hear rhythmic figures which are reminiscent of Novelty Piano Ragtime, when the walking bass is more reminiscent of Stride Ragtime. So we are hearing two different ragtime styles juxtaposed next to one another. This is how he does it and gets away with it.

This rag has much longer sections than a regular rag, and much longer contrasting sections, but I think it can be made to work. I had the privilege of hearing one of the greatest pianists of all time, David Burge (in a concert in Wellington, New Zealand) play this work. It absolutely blew the whole audience away and its light-heartedness and effervescence lifted everyone up after a long concert of very challenging but interesting twentieth century piano works. In fact, this work was specifically written by Albright for Burge.

A word needs to be said about Albright’s piano playing. And that word is, “wow.” It is very easy to simply sit back and be washed away by Albright’s phenomenal technique and piano pyrotechnics, executed cleanly and effortlessly, with exceptional contrasts in both tone and dynamics. He was obviously an unusually fine and gifted pianist. So the question remains as to what kind of pianists might have had both the inclination towards ragtime, and the substantial technical “chops” to really bring out all the inner voices and sophisticated musical ideas of these piano rags. Obviously, David Burge and Albright did. Paul Jacobs could have done it, no sweat. Anthony de Mare could. Gary Smart could. Playing as well as I did 30 years ago, I could have done it back then. But the list remains short.

I suspect that part of the reason for the seven-year wait between recording and releasing this album would have been the heady sophistication of both the piano playing and the music itself. I don’t think a lot of people would have understood it back then. I’m not sure that many would now. But this does not deny the importance of this album, its music, its playing, and Albright’s legacy to ragtime and the recording industry. Simply put, this record is in most respects, preternatural.

Conclusion

If we are to get really, really, real about these four albums, it is safe to say that there is close to no chance that any of them will ever be re-released on compact disc, and made available to a greater public. They will always remain distant, mythical creatures. If you want to hear them, you’ll have a very hard time finding copies, and even then you’ll need a decent turntable and needle to fully appreciate them.

Before he died in 1994, Donald wrote to me and stated that George Buck intended to re-release his album but wanted a few more pieces to go with it. I called up a producer at Jazzology shortly after Donald died, who assured me that the album would be released the following year. Unfortunately, it never happened. Donald recorded those extra pieces, but his newer recordings were lost until they were released about ten years ago on the newer Sunshine and Shadow CD set on New World Records.

While it is sad that the first three albums examined did not get the distribution they deserved, it did not help that the timings for the individual pieces were not listed on the album cover. This most certainly would have assisted in getting much-needed “air-time.” Although timings of individual tracks on records probably didn’t start until approximately 1955, it is more likely than not that the practice probably caught on around 1960, some years before the release of the earliest album discussed, so this is something which was clearly overlooked.37

Even as late as 1980, Albright’s album was also not able to get decent distribution, although I know a number of libraries were to buy copies of it through Musical Heritage Society, which operated sort of like a subscription book club.

Although William Albright, Peter Lundberg, and Max Morath were not included in the “Ragtime Revival” section of Rags and Ragtime,38 it is important to note that the three Jazzology albums herein discussed became the basis for the information on modern ragtime works in this book for the music of Donald Ashwander, Bill Bolcom, and Thomas Shea.

Writing this article and praising all this exceptional music and playing, when almost no readers will be able to hear the music is a little like reading about a great work of art which is in a private collection in someone’s living room, you can’t take photographs, and only one person can see it. It’s a little frustrating. Through these words, it is hoped that more people will know about these substantial and important contributions to American (and world) culture, and that perhaps, one day, they might be readily available to those who might be interested.

© 2022 Matthew de Lacey Davidson

DISCOGRAPHY OF ALBUMS DISCUSSED

-

They All Play[ed] Ragtime, Jazz Piano Heritage Series – Volume 2, Jazzology, JCE-52

-

Donald Ashwander, Ragtime: A New View, Jazz Piano Heritage Series – Volume 21, Jazzology, JCE-71

-

Bolcom Plays His Own Rags [William Bolcom, piano]. Jazz Piano Heritage Series – Volume 22, Jazzology, JCE-72

-

Albright Plays Albright: William Albright, Piano, Musical Heritage Society, MHS 4253

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hasse, John Edward (editor), Ragtime: Its History, Composers, and Music, Schirmer Books, New York, 1985

Jasen, David. A., and Tichenor, Trebor Jay, Rags and Ragtime: A Musical History, Dover Publications, Mineola, New York, 1989.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Amy Cantu of the AADL Archives, Ann Arbor Public Library, for information concerning William Albright. Serious gratitude is also due to Rebecca Hunt, Performing Arts Librarian, Research Services Department, Boston Public Library for her small study on the beginnings of the listing of timings for individual tracks on vinyl LP records. After initial publication, Rebecca very courteously provided me with the following information: Bill’s Nonesuch album, Heliotrope Bouquet has been made available in its entirety on archive.org.[i] Sadly, Albright Plays Albright and Ragtime: A New View are only available on the same site in 30 second samples per track, and Bill’s Jazzology album is not there at all. However the book, They All Played Ragtime, is available to borrow on that same site.[ii] Thanks again to Rebecca.

[i] https://archive.org/details/lp_heliotrope-bouquet-piano-rags-1900-1970_william-bolcom

[ii] https://archive.org/details/theyallplayedrag00blesh

ENDNOTES

1 Morath, Max, Liner notes, p. 2, The World of Scott Joplin compact disc, Vanguard Records, A Welk Music Group Company, 1973.

2 https://www.discogs.com/artist/1884923-Knuckles-OToole These recordings were initially performed by Billy Rowland, and later by Dick Hyman.

4 Bob Darch did release some albums which were of genuine ragtime interest, such as Ragtime Piano, from 1960: https://www.discogs.com/master/1566161-Bob-Darch-Ragtime-Piano

5 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VMSohjXVT7c This recording, made in 1985, does have a few pieces which are rags rather than songs, e.g. That Teasin’ Rag, Carbolic Acid Rag, and Scott Joplin’s Maple Leaf Rag.

6 Jasen and Tichenor, pp. 267 – 270

7 These were later released on CD by Solo Art recordings in 1995: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VqyWJsnmDWQ

8 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3OYENetpEHA , this has also been released on compact disc, https://www.discogs.com/master/408169-Luckey-Roberts-Willie-The-Lion-Smith-Luckey-The-Lion-Harlem-Piano

9 In an email to the author dated August 26, 2022, Peter Lundberg states that before the film, The Sting, and the consequential Joplin/Ragtime revival, there were really only three prominent people bringing ragtime to the public’s attention: Bob Darch, Johnny Maddox, and Max Morath.

10 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B3YCDbb7nHQ&t=1s This is an interview with Max Morath for Rocky Mountain PBS in 2016, where he discusses his early work.

13 Email from Peter Lundberg to the author, August 21, 2022

14 Shea also recorded it for Stomp Off Records, https://www.discogs.com/release/11351700-Tom-Shea-Little-Wabash-Special, and Ragtime Society Records, https://www.discogs.com/release/5756786-Tom-Shea-Prairie-Ragtime

15 https://www.discogs.com/master/1004063-Joseph-Lamb-A-Study-In-Classic-Ragtime You can hear this piece with a YouTube attachment to the website.

16 In his liner notes on the back cover, Blesh discloses that it comes from the LP Folkways FG-3562, and that Folkways and recordist Samuel Charters gave permission of its inclusion on the Jazzology album.

17 https://catalogue.swanngalleries.com/Lots/auction-lot/%28RAGTIME%29-JOPLIN-SCOTT-ET-AL-Small-but-exceptional-archive-o?saleno=2377&lotNo=460&refNo=699420

19 Email from Peter Lundberg to author, dated August 24, 2022

20 Email from Galen Wilkes to author, dated August 26, 2022

21 In an email to the author dated August 21, 2022, Peter states:” I was rathe[r] aiming at some[thing resembling] Brahms’ Hungarian [Dances].”

22 Email from Peter Lundberg to author, dated August 21, 2022

23 Ibid

24 In an email to the author dated August 22, 2022, Peter states that the recording engineer was “Erik Johnsson, pianist and conductor at Liseberg, the amusement park in Göteborg (and the largest in Scandinavia). Apart from conducting and working with artists of [all kinds], his big interest was sound technology and [at the time] he was supposed…to have [had] the largest private collection of sound effects in Sweden.”

25 Email from Peter Lundberg to author, dated August 21, 2022

26 Ibid

27 Email from Peter Lundberg to author, dated August 24, 2022

28 Blesh states as such unequivocally in the liner notes, to wit, “…I believe…that it might be a historic document of ragtime’s rebirth, a musical chronicle of that time at mid-century when love rolled back the stone of long neglect and a much-loved American music was resurrected…” of what he earlier describes as, “…a unique concert by seven player-composers recording in three countries and playing both their own compositions and several first-period rags that had their first, delayed publication in the recent third edition of They All Played Ragtime…”

30 The only other similar album of which I am aware was Tony Caramia’s compact disc Brass Knuckles released in 1997

31 I was to re-record Donald’s On The Highwire album myself in 1998 and released it in 2000. Furthermore, Donald’s family released Donald’s original 1989 recordings on the New World Records release, Sunshine and Shadow in 2013.

33 Jasen & Tichenor, p.103.

35 Confirmed in an email to the author from Amy Cantu, AADL Archives, Ann Arbor Public Library, dated September 19, 2022.

36 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Musical_Heritage_Society

37 I would have thought that there would be readily available information as to when timings for individual tracks on LP vinyl records became prevalent, but it appears not. Rebecca Hunt, Performing Arts Librarian for the Boston Public Library did a very small study for me with the BPL’s collection of LPs which is currently being digitized on archive.org. In an email dated September 22, 2022, she stated that she limited herself to the jazz LP vinyl records, starting in 1949. The first date she observed where this information became available anywhere on an album (either on the record label or on the cover), was 1955, and there were very few. She then observed that the practice did not really catch on until about 1960. While this topic is clearly in need of further study at some point, and this is not exhaustive information, it is a really important start to our understanding of the modern recording industry, and I am very much in Ms. Hunt’s debt for providing this information which seems almost impossible to discover. And it indicates that the practice was, most likely, relatively commonplace by 1966.

38 Jasen & Tichenor, pp. 259 – 289

Matthew de Lacey Davidson is a pianist and composer currently resident in Nova Scotia, Canada. His first CD,Space Shuffle and Other Futuristic Rags(Stomp Off Records), contained the first commercial recordings of the rags of Robin Frost. Hisnew Rivermont 2-CDset,The Graceful Ghost:Contemporary Piano Rags 1960-2021,is available atrivermontrecords.com.A 3-CD set of Matthew’s compositions,Stolen Music: Acoustic and Electronic Works,isavailable through The Sousa Archives and Center for American Music University of Illinois (Champaign/Urbana),sousa@illinois.edu.