January 10, 2021, Another Milestone Anniversary Not To Be Forgotten

The centennial of the Jazz Age is upon us, and it has been commemorated with acknowledgment of generally recognized milestones in the evolution of the music. Although not without controversy, dates are convenient in that they mark an event we can point to as a watershed after which the historical record, more or less, confirms something changed.

For most music historians, applying this methodology to jazz began four years ago with the first recording of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band on February 26, 1917. Recent additions include Mamie Smith’s recording of “Crazy Blues” on August 10, 1920, which gave rise to the “race record” industry, and births of future jazz greats such as Charlie Parker on August 29, 1920. But one event, surely to be overlooked, transformed the playing style of an entire generation of pianists and changed the course of jazz piano. On January 10, 1921, James P. Johnson joined the roster of the QRS Music Company.

Recording technology then still relied on the acoustic method requiring musicians to play into a large input horn. The piano was at a distinct disadvantage, and was generally poorly recorded. The piano roll, however, allowed a high fidelity performance in everyone’s living room. It became the predominant form of parlor entertainment in the early 1920s. Radio and electronic recording technology would supplant it, but they were several years away from widespread use.

The perforated paper roll, as it wound its way through the ingenious pneumatic mechanism of the player piano, reproduced an actual performance on an actual piano. Although some rolls were heavily “arranged” with many added notes, hand played rolls contained much more of what a pianist played. In 1921, QRS was the largest manufacturer of piano rolls in the country. Every sort of music was produced—classical repertoire, popular songs, religious tunes, ragtime, and the blues. Every type of ethnic performer was represented—almost. But Mamie Smith’s records proved there was a new market for African American music played by African Americans, and QRS wanted in.

In mid-1920, James P. Johnson had just returned from a two-year sojourn through the Midwest. He had left New York as one of the most prominent ragtime pianists but with clear hints at an evolving piano style. Jazz burst on to the scene in 1917 predominantly as an instrumental ensemble music. Piano styles were still strongly tied to ragtime with increasing doses of flashy novelty effects. In 1920, Jelly Roll Morton and Earl Hines were several years away from their first recordings.

But Johnson arrived back in New York with something new. He was playing continuously in Harlem and on Clef Club gigs, the prestigious booking agency founded by James Reese Europe the decade before. Johnson’s style had matured, and the rhythmic complexity he pioneered while incorporating the blues essence he absorbed in the Midwest moved the music beyond the straightforward syncopations of ragtime and the momentary dazzle of a virtuosic piano trick. Simply put, he made the music swing.

On January 10, 1921, James P. Johnson became the first African American pianist to be contracted by the QRS Music Company. On occasion in the past, they had engaged Black pianists for one-off recordings, but had no one on their regular recording staff. The addition of Johnson was a big deal. The news spread across the country in syndicated newspaper articles in the African American press proclaiming this ground-breaking initiative. Johnson had negotiated himself a good contract with a monthly retainer, royalties for his own tunes, and the ability to place them with other recording and roll companies—all quite remarkable for an African American musician at that time.

On January 10, 1921, James P. Johnson became the first African American pianist to be contracted by the QRS Music Company. On occasion in the past, they had engaged Black pianists for one-off recordings, but had no one on their regular recording staff. The addition of Johnson was a big deal. The news spread across the country in syndicated newspaper articles in the African American press proclaiming this ground-breaking initiative. Johnson had negotiated himself a good contract with a monthly retainer, royalties for his own tunes, and the ability to place them with other recording and roll companies—all quite remarkable for an African American musician at that time.

QRS looked to promote the music of their new African-American staff member not only to Black audiences but also to the broader public. As was their practice, QRS wanted a publicity photo. Johnson sat at an upright piano, head turned toward the camera. His long spindly fingers stretching across the keyboard belie his somewhat diminutive stature of five foot six inches. He signed at least three copies: “James P. Johnson 1921.” (Two are known to exist).

QRS looked to promote the music of their new African-American staff member not only to Black audiences but also to the broader public. As was their practice, QRS wanted a publicity photo. Johnson sat at an upright piano, head turned toward the camera. His long spindly fingers stretching across the keyboard belie his somewhat diminutive stature of five foot six inches. He signed at least three copies: “James P. Johnson 1921.” (Two are known to exist).

QRS advertised widely in the mainstream white press as well. They noted his Clef Club bonifides, and reproduced in the ads the now well-known publicity photo of him sitting at the piano. QRS had manufacturing plants and distributors all over the US and internationally, including Buenos Aires, Sydney, and London. Johnson later recalled to an interviewer his rolls “were a hit.”

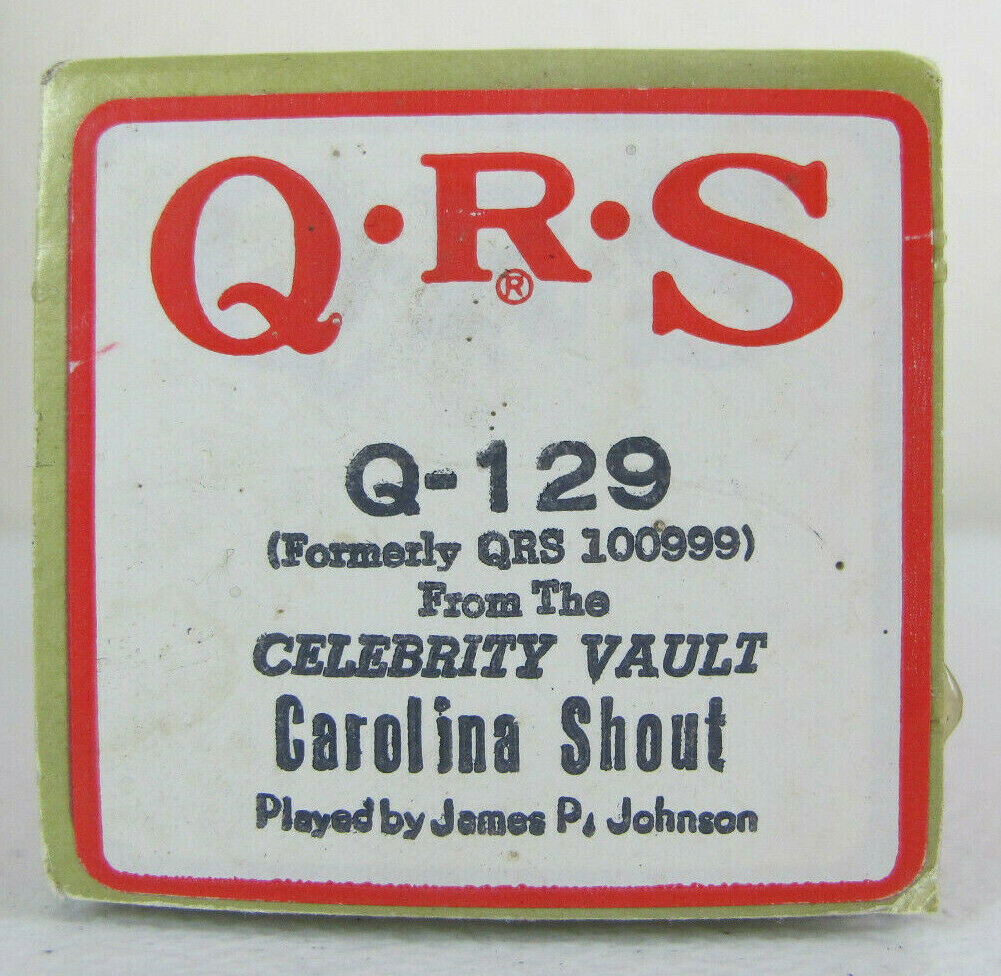

One of the first of his own tunes he cut in the spring of 1921 changed jazz history. In 1918 Johnson had recorded “Carolina Shout” for a little known roll maker in Newark, NJ. It clearly embodied a departure from ragtime but was still a nascent conception and was hampered by sloppy editing. He re-cut it for QRS, and it caught the attention of every pianist along the Northeast, including young Thomas “Fats” Waller in New York and Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington in Washington, DC. They learned the piece by slowing down the player piano so they could place their fingers in the depressed keys. Johnson’s other rolls provided additional tutorials on the new style. As Ellington said, he “nursed it and rehearsed it.”

Decades later, Johnson’s style became known as Harlem Stride Piano, and influenced pianists for decades including Count Basie, Art Tatum, Erroll Garner, and Thelonious Monk. In many respects every pianist that came after Johnson could not be untouched by his music.

He would eventually become known as the “Father of Harlem Stride Piano,” but during his lifetime he was referred to as the “Dean Of Jazz Pianists.” Johnson went on to have a vast career in American music as composer for over forty stage shows, one of which, Runnin’ Wild, included “The Charleston,” the signature tune of the 1920s. (Link is to Carroll Gibbons Orch, 1925). His contributions as favorite accompanist for Bessie Smith and Ethel Waters, and as composer of concert music based on African-American musical roots, including a one-act opera with noted Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes, place him in a rare category of American musicians whose reach and influence are broad and deep.

But it was his breakthrough musically and socially with QRS that can be seen as a sea change not reliant on historical interpretation decades later. His real-time impact changed the sound of the music. So let’s mark January 10, 1921, along with the other jazz milestones, as the day modern Jazz piano was born, thanks to the innovation of James P. Johnson.

Scott E. Brown, MD, MA, is the biographer of James P. Johnson. His first book was published in 1987. He holds a Masters Degree in Jazz History and Research from Rutgers University-Newark, N.J. His Masters thesis on Jaki Byard is available on Google Scholar. Dr.Brown’s new biography of Johnson is expected in 2025.