Beatrice C. “Bee” Palmer (11 September 1894 – 22 December 1967) was born in Chicago, the third of four children born to Charles and Anna Larsen Palmer who had emigrated from Sweden eleven years previously. Bee popularized the shimmy dance, described as “a sinuous and suggestive undulation of hips and shoulders,” and claimed the title “Shimmie Queen” in 1918. Bee Palmer was a very magnetic performer, singing popular songs in a sensuous manner that was guaranteed to shock or attract, and her shimmy dance was highly acclaimed.

Beatrice C. “Bee” Palmer (11 September 1894 – 22 December 1967) was born in Chicago, the third of four children born to Charles and Anna Larsen Palmer who had emigrated from Sweden eleven years previously. Bee popularized the shimmy dance, described as “a sinuous and suggestive undulation of hips and shoulders,” and claimed the title “Shimmie Queen” in 1918. Bee Palmer was a very magnetic performer, singing popular songs in a sensuous manner that was guaranteed to shock or attract, and her shimmy dance was highly acclaimed.

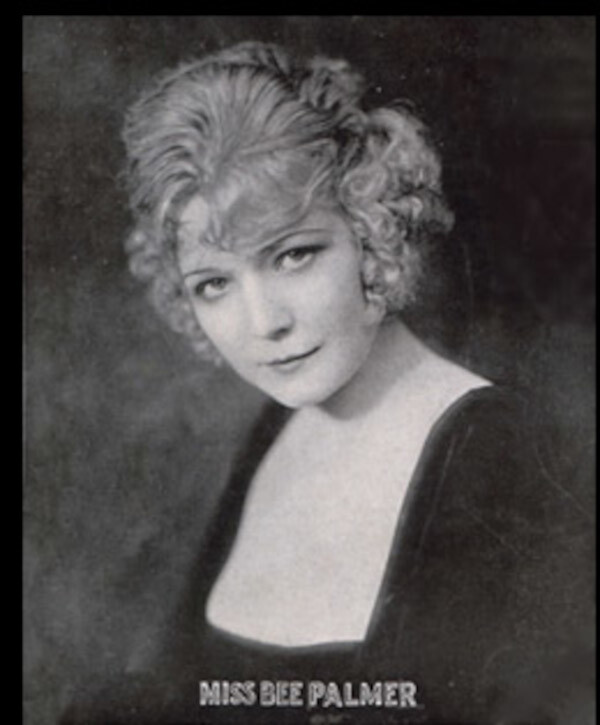

Bee was an attractive blonde of about 5’7” who went to New York to act in vaudeville, where she became a Ziegfeld Girl in 1918. She made her debut in the Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic on July 15, 1918, where she was described as “a singing and dancing soubrette and pianist of unusual magnetism.” She performed the song “I Want To Learn To Jazz Dance” and another song in a program of fifteen numbers, on a bill with leading stars Lillian Lorraine and Bert Williams.

For the next two years, Bee appeared in the Midnight Frolic again in 1919 and in various other Broadway productions along with such top entertainers as Eddie Cantor, Fannie Brice, W.C. Fields, and Will Rogers. At the beginning of  November 1920, she decided to go on the road with her own revue called “Oh Bee!” The show, written for her by Herman Timberg, incorporated singing, shimmying, and jazz music provided by her own band. On November 5, Variety falsely reported Bee’s marriage to her pianist, Al Siegel.

November 1920, she decided to go on the road with her own revue called “Oh Bee!” The show, written for her by Herman Timberg, incorporated singing, shimmying, and jazz music provided by her own band. On November 5, Variety falsely reported Bee’s marriage to her pianist, Al Siegel.

Her first performance of “Oh Bee!” on the Orpheum circuit, scheduled for November 12, was cancelled because her costumes did not arrive. She continued on tour through the fall and winter of 1920-21, playing in Memphis, New Orleans, Milwaukee, and Chicago. While in New Orleans at the beginning of December, she picked up several new musicians: drummer Johnny Frisco, seventeen-year-old cornetist Emmett Hardy, clarinetist Leon Roppolo, and trombonist Santo Pecora. Her former accompanists Dick Himber and pianist Al Siegel also remained with the act, and the troupe was now renamed “Bee Palmer and Her New Orleans Rhythm Kings.”

Bee received mixed reviews from the media. The Milwaukee Evening Sentinel of December 21 wrote

“…Bee can wiggle and squirm and sway with the best in the business, but she seems a trifle ashamed of herself, as, indeed, she ought to be.”

The Milwaukee Journal critic was even harsher, writing,

“Miss Palmer is a buxom, exceedingly blond young person, with the best of intentions, but an exceedingly unfortunate method of putting them into effect. Her dancing is not quite bad enough to be shocking, and not quite good enough to be passable. Now and then she sings, which she shouldn’t.”

Perhaps the act was still developing, for when she played Milwaukee again on January 3, 1921, the Sentinel mentioned that it

“boasted a professional veneer that it missed when formerly offered here.”

In January 1921, Bee’s agent, Max Hart, filed suit against her for $6,000 worth of commissions and management fees. He attached her clothing, scenery, and traveling trunks, making it impossible for her to tour. She was forced to remain in Chicago, and the temperamental star had resigned from one week’s booking four times – once after each show. Finally, in mid-February, Bee offered Hart a settlement of $1,500, which he accepted.

From February 27 through March 2, 1921, Bee Palmer and Company played at Davenport, Iowa’s Columbia Theater. According to Esten Spurrier, he and a young Bix Beiderbecke, both budding cornetists, attended every single one of these shows and listened to the great music. The New Orleans men were among the top young jazz musicians, and Pecora and Roppolo were to become legendary.

From February 27 through March 2, 1921, Bee Palmer and Company played at Davenport, Iowa’s Columbia Theater. According to Esten Spurrier, he and a young Bix Beiderbecke, both budding cornetists, attended every single one of these shows and listened to the great music. The New Orleans men were among the top young jazz musicians, and Pecora and Roppolo were to become legendary.

On March 3, 1921, before Bee and her band left Davenport for Peoria, she secretly married her pianist Al Siegel in a midnight ceremony at a judge’s office in the local Masonic Temple. On the marriage license application, Al gave his age as 24 and Bee gave hers as 23. She was actually 27. The Davenport Democrat and Leader reported that Bee “evidenced all the confusion and embarrassment of the unsophisticated school-girl bride and seemed extremely happy when the ceremony had ended.” The bride sported a large purple hat instead of the typical veil.

On March 3, 1921, before Bee and her band left Davenport for Peoria, she secretly married her pianist Al Siegel in a midnight ceremony at a judge’s office in the local Masonic Temple. On the marriage license application, Al gave his age as 24 and Bee gave hers as 23. She was actually 27. The Davenport Democrat and Leader reported that Bee “evidenced all the confusion and embarrassment of the unsophisticated school-girl bride and seemed extremely happy when the ceremony had ended.” The bride sported a large purple hat instead of the typical veil.

Bee’s act was beset with public criticism and bad reviews, mainly due to public perception that the shimmy was risqué. Even today, she is often referred to as a stripper, not a singer or dancer. Most reviewers who saw “Oh Bee!” realized that it wasn’t any more offensive than any other theatrical offering, but clergymen nationwide were speaking out against the shimmy and other “modern dances,” and so nervous theater managers in Peoria cancelled the tour.

Bee’s act was beset with public criticism and bad reviews, mainly due to public perception that the shimmy was risqué. Even today, she is often referred to as a stripper, not a singer or dancer. Most reviewers who saw “Oh Bee!” realized that it wasn’t any more offensive than any other theatrical offering, but clergymen nationwide were speaking out against the shimmy and other “modern dances,” and so nervous theater managers in Peoria cancelled the tour.

After this, the band members went in several directions to find work. Roppolo, Pecora, and Hardy went back to Davenport to play with Carlisle Evans’ band, and after that, played on the steamer “Capitol.” Bee joined the Evans band for a short time as a guest star. By the end of April, she was back in New York at the Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic.

In October, 1921, Bee’s husband Al Siegel filed suit against boxer Jack Dempsey for alienation of affections, charging that Dempsey lured Bee away from her marital home while both Jack and Bee were on the Orpheum Circuit. Dempsey said the charges were ridiculous and that Bee wasn’t his type. In the end, the whole matter was dropped.

In October, 1921, Bee’s husband Al Siegel filed suit against boxer Jack Dempsey for alienation of affections, charging that Dempsey lured Bee away from her marital home while both Jack and Bee were on the Orpheum Circuit. Dempsey said the charges were ridiculous and that Bee wasn’t his type. In the end, the whole matter was dropped.

Bee filed for divorce against Siegel in the same month on the grounds of cruelty, saying that he beat her. She told reporters, “I picked him out of the gutter. I married him at midnight on the impulse of the moment.” Al, at this time accompanist for Sophie Tucker, also filed for divorce. However, they remained married for another seven years.

Bee continued to appear on Broadway throughout the later 1920s. She starred in the “Passing Show of 1924” at the Winter Garden, and was supposed to have been accompanied by Fletcher Henderson’s Orchestra, although the plans never materialized. From 1918 through 1925, Bee Palmer made several test recordings for both Columbia and Victor, none of which were ever issued.

Al Siegel recorded a few sides under his name for the Paramount label in 1924. Bee seems to emerge again and again as an ally to hot jazz musicians, although plans didn’t always work out. In mid-1928, Bee hired Eddie South to lead her backup band for an engagement at the College Inn in Chicago.

Bee had intended to work with Condon’s Chicagoans, including Eddie Condon, Gene Krupa, and his other bandmates at a new club, the Chateau Madrid, in New York in 1928. However, Bee and Al had one of their many fallings-out, and after a rehearsal of the band, an unimpressed club manager fired the band without ever having hired them. Bee also seemed to have played a part in bringing New Orleans guitarist Edward “Snoozer” Quinn to the Paul Whiteman Orchestra in 1929.

In 1928, Bee Palmer finally divorced her husband Al Siegel. After the split-up, Siegel soon attached himself to a new and fast-rising star, a former stenographer named Ethel Zimmerman. By 1930, the singer, now Ethel Merman, was on her way to stardom, with Al Siegel as her coach and accompanist.

On December 23, 1928, Paul Whiteman gave a concert at Carnegie Hall, with Bee Palmer as an added attraction. This concert was for the benefit of the Northwoods Sanitarium in Saranac Lake, New York, where show business patients were treated for tuberculosis. Universal Pictures filmed the concert for possible use in the motion picture planned with Whiteman in the following year. The film, “King Of Jazz“, was finally completed in 1930, but did not include any of the footage from the Carnegie Hall concert.

At the beginning of 1929, Bee Palmer was a part of the New York social scene. Her parties and jam sessions were the talk of the entertainment business, and Paul Whiteman’s men were among the regular guests. At the insistence of several of his musicians, Paul Whiteman sponsored a recording session on January 10, 1929, after two other songs were recorded by the full orchestra. At this session, she recorded “Singin’ The Blues” and “Don’t Leave Me, Daddy” for Columbia, backed by Frank Trumbauer and a group of Whiteman musicians. Arranger Bill Challis recalled that it was actually pianist Lenny Hayton, not Frank Trumbauer, that organized this session, as Bee Palmer was Lenny Hayton’s girlfriend at the time.

At the beginning of 1929, Bee Palmer was a part of the New York social scene. Her parties and jam sessions were the talk of the entertainment business, and Paul Whiteman’s men were among the regular guests. At the insistence of several of his musicians, Paul Whiteman sponsored a recording session on January 10, 1929, after two other songs were recorded by the full orchestra. At this session, she recorded “Singin’ The Blues” and “Don’t Leave Me, Daddy” for Columbia, backed by Frank Trumbauer and a group of Whiteman musicians. Arranger Bill Challis recalled that it was actually pianist Lenny Hayton, not Frank Trumbauer, that organized this session, as Bee Palmer was Lenny Hayton’s girlfriend at the time.

The songs were scheduled for issue on Columbia’s Whiteman label with the banner “Paul Whiteman presents Bee Palmer with the Frank Trumbauer Orchestra”. However, all three takes of each song were rejected by Columbia. Some of the rejected takes (takes 1 and 3 of “Singin’ The Blues” and take 2 of “Don’t Leave Me, Daddy”) have been released on CD.

Bee Palmer’s vocal in “Singin’ The Blues” is noteworthy as an early example of vocalese, or singing lyrics written to fit a recorded instrumental solo. Here, lyrics were specially written by Ted Koehler to fit the solos of Bix and Tram from their 1927 Okeh recording of the song. Another vocalese version of “Singin’ The Blues” was recorded by Marion Harris in August 1934 on English Decca. Bee Palmer also recorded the song “Don’t Leave Me, Daddy” at the same recording session. Marion Harris also recorded the song “Don’t Leave Me, Daddy” in October of 1916.

In 1930, Bee co-wrote the song “Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone” with Sidney Clare and Sam H. Stept, and introduced the song to audiences at that time. It is interesting that some later issues of the sheet music for this song did not include Bee’s name. Her glamorous photo appeared on that sheet music, as well as on the sheet music for “I Want to Shimmie,” which she introduced in the Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic of 1919, “What Can I Say After I Say I’m Sorry” (1926) and “Let’s Talk About My Sweetie” (1926).

In 1930, Bee co-wrote the song “Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone” with Sidney Clare and Sam H. Stept, and introduced the song to audiences at that time. It is interesting that some later issues of the sheet music for this song did not include Bee’s name. Her glamorous photo appeared on that sheet music, as well as on the sheet music for “I Want to Shimmie,” which she introduced in the Ziegfeld Midnight Frolic of 1919, “What Can I Say After I Say I’m Sorry” (1926) and “Let’s Talk About My Sweetie” (1926).

The two rehearsal recordings linked on this page were made at the Green Recording Studios in the Lyon and Healy Building in Chicago, Illinois, and were made in the latter part of 1932, or perhaps 1933.

[Ed. Note: the recordings referred to in this section were not saved in Archive.org’s Wayback Machine and so are not available to include in this recreation of the Red Hot Jazz Archive. The only available recording was a single take of “Singing the Blues“. The deterioration of this digital archive over time is one of the reasons we have undertaken saving what we can of the old redhotjazz.com. ]

One of these songs, “I Gotta Right To Sing The Blues”, was a hit song from Earl Carroll’s Vanities of 1932, which opened on Broadway in September of that year. Bee was accompanied on this song and the song with (Unknown Title) by David Rose, a pianist working in the Chicago area who was a pianist and arranger for Ted Fio Rito’s band from 1927-1929.

In later years, David Rose became famous for such compositions such as “Holiday for Strings” and “The Stripper”. The collaboration of Bee Palmer and David Rose was suggested by fellow musician Bill Alamshah, who was a trumpet player that led his own band under the name Bill Shaw in 1932 or 1933. Bill also managed Frank Trumbauer’s band in 1937 after Tram left Paul Whiteman’s orchestra. Bee Palmer used David Rose as an accompanist, but only for private practice sessions that Bill also attended.

By 1933, Bee was living in Chicago, near her parents. In December of that year, she married her current pianist, variously named as Jack Finna or Pinna, in a quiet ceremony in Waukegan, Illinois. After that, she seems to have faded from the public eye. Her style of singing was more suited to the vaudeville stage than the nightclub, and the shimmy for which she was famous had passed into obscurity.

In 1954, a column by Earl Wilson mentioned a planned movie project about Bee Palmer and Al Siegel, but it never made it to the big screen. Bee Palmer died on December 23, 1967, at the age of 73. —by Dennis Pereyra and Suzanne Fischer

For more information about the life and music of Bee Palmer, please see David Garrick’s Music Pages. Additional thanks to Scott Black for providing the clippings used with this article.

| Title | Recording Date | Recording Location | Company |

| At Half-Past Nine (accompanied by Prince’s Orchestra) |

6-3-1918 | New York, New York | Columbia (Rejected) |

| Don’t Leave Me, Daddy (take 1) (Joe Verges) (Paul Whiteman presents Bee Palmer with the Frank Trumbauer Orchestra) |

1-10-1929 | New York, New York | Columbia (Rejected) |

| Don’t Leave Me, Daddy (take 2) (Joe Verges) (Paul Whiteman presents Bee Palmer with the Frank Trumbauer Orchestra) |

1-10-1929 | New York, New York | Columbia (Rejected) * |

| Don’t Leave Me, Daddy (take 3) (Joe Verges) (Paul Whiteman presents Bee Palmer with the Frank Trumbauer Orchestra) |

1-10-1929 | New York, New York | Columbia (Rejected) |

| I Gotta Right To Sing The Blues (accompanied by David Rose on piano) (Harold Arlen – Ted Koehler) |

c. 1932 | Chicago, Illinois | rehearsal recording * (Arcadia LP 2014) |

| I’ll See You In My Dreams (accompanied by violin and piano) (Isham Jones) |

7-14-1925 | Camden, New Jersey | Victor test (un-numbered) (Rejected) |

| I’m Coming, Virginia (unknown accompaniment) (Will Marion Cook / Donald Heywood) |

5-10-1928 | New York, New York | Victor test (un-numbered) (Rejected) |

| Singin’ The Blues (take 1) (Sam Lewis / Joe Young / Con Conrad / J. Russell Robinson / special lyrics – Ted Koehler) (Paul Whiteman presents Bee Palmer with the Frank Trumbauer Orchestra) |

1-10-1929 | New York, New York | Columbia (Rejected) * |

| Singin’ The Blues (take 2) (Sam Lewis / Joe Young / Con Conrad / J. Russell Robinson) (Paul Whiteman presents Bee Palmer with the Frank Trumbauer Orchestra) |

1-10-1929 | New York, New York | Columbia (Rejected) |

| Singin’ The Blues (take 3) (Sam Lewis / Joe Young / Con Conrad / J. Russell Robinson / special lyrics – Ted Koehler) (Paul Whiteman presents Bee Palmer with the Frank Trumbauer Orchestra) |

1-10-1929 | New York, New York | Columbia (Rejected) * |

| Sweet Georgia Brown (accompanied by violin and piano) (Maceo Pinkard / Kenneth Casey / Ben Bernie) |

7-14-1925 | Camden, New Jersey | Victor test (un-numbered) (Rejected) |

| The Bee Palmer Strut (no vocal, accompanied by violin, guitar and piano) |

7-14-1925 | Camden, New Jersey | Victor test (un-numbered) (Rejected) |

| (Unknown Title) (accompanied by David Rose on piano) |

c. 1932 | Chicago, Illinois | rehearsal recording * (Arcadia LP 2014) |

| When Alexander Takes His Ragtime Band To France (accompanied by C. Coolidge on piano) (Alfred Bryan / Cliff Hess / Edgar Leslie) |

5-15-1918 | New York, New York | Victor test (un-numbered) (Rejected) |

| Artist | Instrument |

| (1/10/1929 Session) | |

| Bix Beiderbecke ???? | Cornet |

| Irving Friedman | Clarinet, Alto Saxophone |

| Lennie Hayton | Piano |

| Min Leibrook | Bass Saxophone |

| Bee Palmer | Vocals, Scat |

| Edward “Snoozer” Quinn | Guitar |

| Bill Rank | Trombone |

| Charles Strickfaden | Alto Saxophone |

| Frank Trumbauer | C-Melody Saxophone, Alto Saxophone |

Redhotjazz.com was a pioneering website during the "Information wants to be Free" era of the 1990s. In that spirit we are recovering the lost data from the now defunct site and sharing it with you.

Most of the music in the archive is in the form of MP3s hosted on Archive.org or the French servers of Jazz-on-line.com where this music is all in the public domain.

Files unavailable from those sources we host ourselves. They were made from original 78 RPM records in the hands of private collectors in the 1990s who contributed to the original redhotjazz.com. They were hosted as .ra files originally and we have converted them into the more modern MP3 format. They are of inferior quality to what is available commercially and are intended for reference purposes only. In some cases a Real Audio (.ra) file from Archive.org will download. Don't be scared! Those files will play in many music programs, but not Windows Media Player.