In 1966, while visiting a friend in San Diego, our conversation turned to my obsession with traditional jazz. My friend said, “I think my dad has a record of old time jazz” and he turned to look through a cabinet full of records. In just a minute he pulled out a 10-inch LP with a blue cover called Burt Bales After Hours. He put the record on the turntable and “New Orleans Joys” came over the speakers. I had just learned the song from Wally Rose’s recording with the Yerba Buena Jazz Band but this was a very different approach to the number! My interest in the music was obvious and I was given permission to borrow the record. I played it until I was afraid that the grooves would wear out. It was a sad day when I had to return the LP to my friend’s father!

In 1966, while visiting a friend in San Diego, our conversation turned to my obsession with traditional jazz. My friend said, “I think my dad has a record of old time jazz” and he turned to look through a cabinet full of records. In just a minute he pulled out a 10-inch LP with a blue cover called Burt Bales After Hours. He put the record on the turntable and “New Orleans Joys” came over the speakers. I had just learned the song from Wally Rose’s recording with the Yerba Buena Jazz Band but this was a very different approach to the number! My interest in the music was obvious and I was given permission to borrow the record. I played it until I was afraid that the grooves would wear out. It was a sad day when I had to return the LP to my friend’s father!

Eventually I found the Good Time Jazz 12-inch LP They Tore My Playhouse Down with the material from After Hours plus piano solos by Paul Lingle. I was the definition of “happy camper” when that record arrived in the mail.

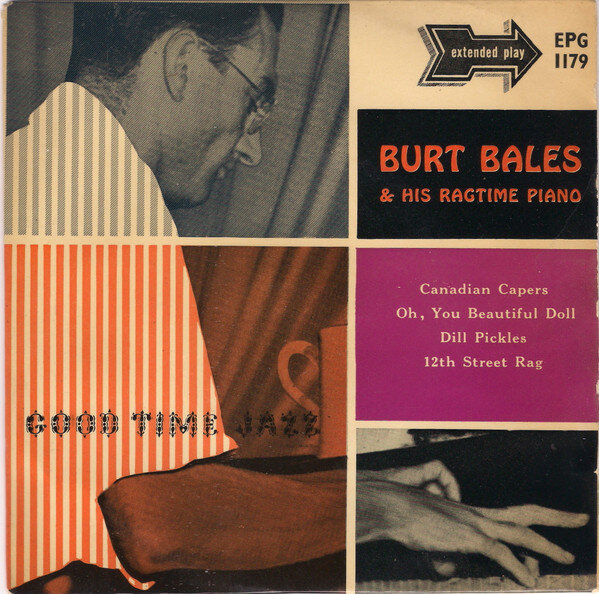

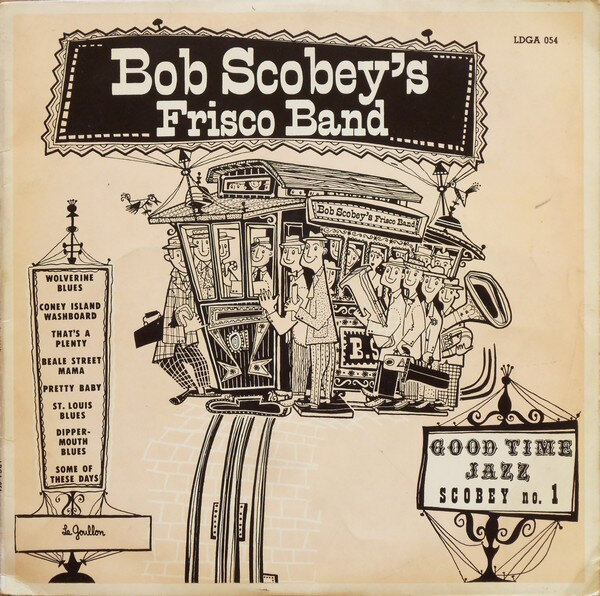

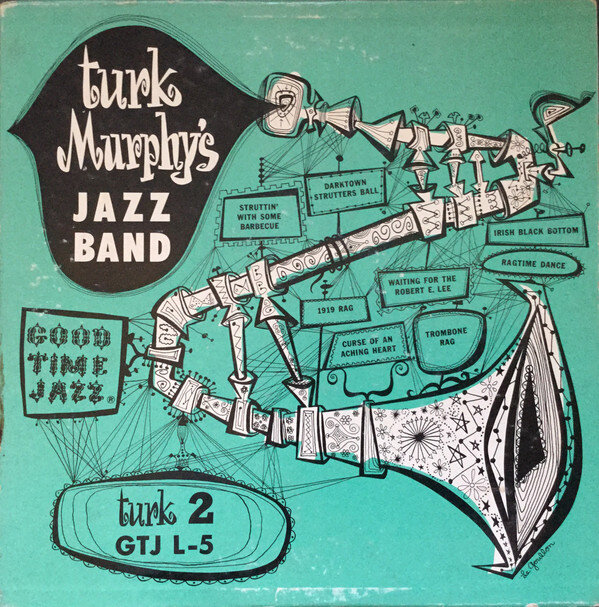

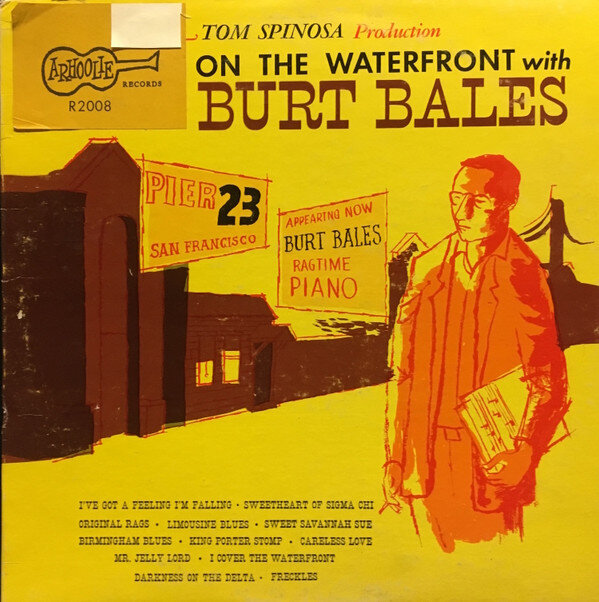

Within a short time I discovered Burt’s recordings with bands: Turk Murphy (1947, 1949, and 1950); Bob Scobey (1950-1951); Bunk Johnson (1944) and finally Benny Strickler with the Yerba Buena Jazz Band (1942). Also, the Arhoolie (ex-Cavalier) On The Waterfront LP of piano solos and a Good Time Jazz EP, where Burt was accompanied by Ed Garland and Minor Hall.

Jelly Roll Morton’s influence was always mentioned prominently in the liner notes of Burt’s records. When I was able to find Morton’s solo records, that inspiration was immediately apparent. However, there were numerous individual variations—particularly in the left hand—that gave Burt a distinctive sound of his own.

Jelly Roll Morton’s influence was always mentioned prominently in the liner notes of Burt’s records. When I was able to find Morton’s solo records, that inspiration was immediately apparent. However, there were numerous individual variations—particularly in the left hand—that gave Burt a distinctive sound of his own.

As much as I wanted to hear Burt Bales in person, it was a difficult task. The California Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control forbade minors to enter an establishment where liquor was served unless food was also available. At that time, most of the places where Burt performed in the Bay Area did not serve food. Finally, in 1970, I was able to hear him at Earthquake McGoon’s in San Francisco when Turk Murphy organized a benefit for an ailing Clancy Hayes that was open to all ages. That was a glorious day of music! I was able to hear Ted Shafer’s Jelly Roll Jazz Band, the Bay City Jazz Band, Turk Murphy’s Jazz Band, Bob Mielke’s Bearcats, Bob Helm, Norma Teagarden, Squire Girsback, Fred Higuera, Dick Oxtot, Wally Rose…and Burt Bales! He sounded as great as ever, especially on a terrific version of Morton’s “Mister Joe.” I would have introduced myself as a fan, but my family had to leave for the airport immediately after Burt’s set.

The next opportunity to hear him came in 1971, at the second and final Clancy Hayes benefit. As before, he played “Mister Joe” with rhythm accompaniment. His performance was one of the highlights of the day.

On a trip to the Bay Area in the summer of 1973, I managed to catch Burt in San Leandro, playing an intermission during a New Orleans Jazz Club of Northern California concert. Finally, I was able to tell him how much I enjoyed his playing and his recordings. He was courteous, although he had to cut the conversation short to leave for another engagement.

After moving to Oakland in 1978, one of my priorities was hearing Burt playing solo at the Washington Square Bar & Grill in San Francisco. The first time I went to the place, Burt made time to talk with me on the intermissions. He mentioned his regular Sunday gig at Dick’s at the Beach (also in San Francisco) and I went there the following weekend. However, with multiple brass, reed, and rhythm players sitting in, it was almost impossible to hear the piano.

In 1979, I played every Friday afternoon with Ev Farey’s Golden State Jazz Band at “Vic’s Place” in the Financial District. After the band had played for several weeks, Burt wandered in one day. He nodded his greetings to the musicians, then sat at the bar, enjoying the sounds. After listening for a while, he asked to sing a number with the band. Ev agreed and Burt sang a great version of “You Brought A New Kind Of Love To Me.” It was a smash hit! The following week, Burt returned to Vic’s for a reprise. It became a regular feature on the gig and the audience always responded with great enthusiasm. There was no piano at Vic’s and I lamented that fact to Burt one time. He replied “That band doesn’t need a pianist!” What a nice compliment for our piano-less rhythm section!

One afternoon as we were talking, Burt excused himself to call a taxi, for a ride back to his apartment. The address was not far off the route I took to the Bay Bridge, so I offered to drive him. The distance from Vic’s Place to Burt’s apartment was not very far, but we were able to have some very interesting, if short, conversations. I still remember some of Burt’s pithy comments…

Drummers: “Grandpa (Edwards) had a heavy foot. (Bill) Dart was a good tap-dancer. Freddie (Higuera) was a GOOD drummer!” Jess Stacy: “Jess couldn’t keep her (Lee Wiley) in furs!” Don Ewell and Ralph Sutton: “I told them to be themselves.”

One comment that initially struck me as strange was when Burt said, “(Lu) Watters had a good ‘Kansas City’ style band.” I turned to look at him with a look of incredulity. He chuckled and said, “You know—like Bennie Moten!” Another time, after mentioning that I would like to play drums in a Bob Scobey-style band his response was a question: “Did Scobey have a style?”

One comment that initially struck me as strange was when Burt said, “(Lu) Watters had a good ‘Kansas City’ style band.” I turned to look at him with a look of incredulity. He chuckled and said, “You know—like Bennie Moten!” Another time, after mentioning that I would like to play drums in a Bob Scobey-style band his response was a question: “Did Scobey have a style?”

For several months in 1979, Burt played at a little bar called The Serenader, on Lakeshore Avenue in Oakland. After the gig at Vic’s, I would drive Burt to Oakland and then back to San Francisco. From time to time I sat in on drums. When I brought my brand-new 14×28” Slingerland bass drum into the club, Burt gave me a hard stare for a few minutes. Finally, he said “Don’t let that bass drum ruin your life!”

The Serenader sessions attracted some wonderful musicians, including cornetist Leon Oakley, bassist Mike Duffy, pianist Ray Skjelbred (on trombone), reedman Richard Hadlock and many others. And the San Francisco—Oakland—San Francisco round trip made longer conversations possible. Once, Burt told me that he was asked to join Louis Armstrong’s All-Stars after Earl Hines left the band. Burt said that he would have accepted the offer, but at the time he was a guest of the State of California (for possession and sale of a controlled substance). Despite missing out on a career-changing opportunity, he was philosophical: “I guess it made some people happy to put me away in jail.”

Burt was on the wagon when he sat in at Vic’s, but during the afternoon he would make a couple trips outside for a “smoke break” (of the non-tobacco variety). He generally stayed out of the public eye during these interludes. But when a publicity photo of the Golden State Jazz Band was taken with the band posed in front of Vic’s, the photographer accidentally captured Burt—leaning against a telephone pole, enjoying his “jive!”

When Chris Tyle was playing cornet with Turk Murphy’s Jazz Band, one night Burt stopped in to hear the band at Earthquake McGoons on the Embarcadero. Chris introduced himself and Burt invited Chris to sit in at Dick’s at the Beach. When Chris told me about it, I wanted to hear the session. When we pulled up in front of Burt’s, he said, “Come on in. I just baked some brownies.” They were delicious! Chris asked, “Burt? Can I have another one?” Burt said “You might want to only have one.” Chris and I had the same expression as we realized that there was an ingredient in the brownies besides flour and chocolate! Neither of us can recall any details regarding the music played at Dick’s that afternoon, but we remember feeling mell-OH.

When Chris Tyle was playing cornet with Turk Murphy’s Jazz Band, one night Burt stopped in to hear the band at Earthquake McGoons on the Embarcadero. Chris introduced himself and Burt invited Chris to sit in at Dick’s at the Beach. When Chris told me about it, I wanted to hear the session. When we pulled up in front of Burt’s, he said, “Come on in. I just baked some brownies.” They were delicious! Chris asked, “Burt? Can I have another one?” Burt said “You might want to only have one.” Chris and I had the same expression as we realized that there was an ingredient in the brownies besides flour and chocolate! Neither of us can recall any details regarding the music played at Dick’s that afternoon, but we remember feeling mell-OH.

On the drives from Oakland to San Francisco and back, Burt told some anecdotes concerning some of the New Orleans Jazz pioneers who were active in the Bay Area. When Bunk Johnson stayed with Burt and his then-wife Jeanne, Bunk developed a crush on Mrs. Bales. Burt recalled that when everyone had gone to bed and the lights were turned off, he would hear a soft falsetto voice coming from Bunk’s room: “Je-ee-anne. Je-ee-anne.” Burt would tolerate it for a few minutes, then yell “SHUT UP, BUNK!”

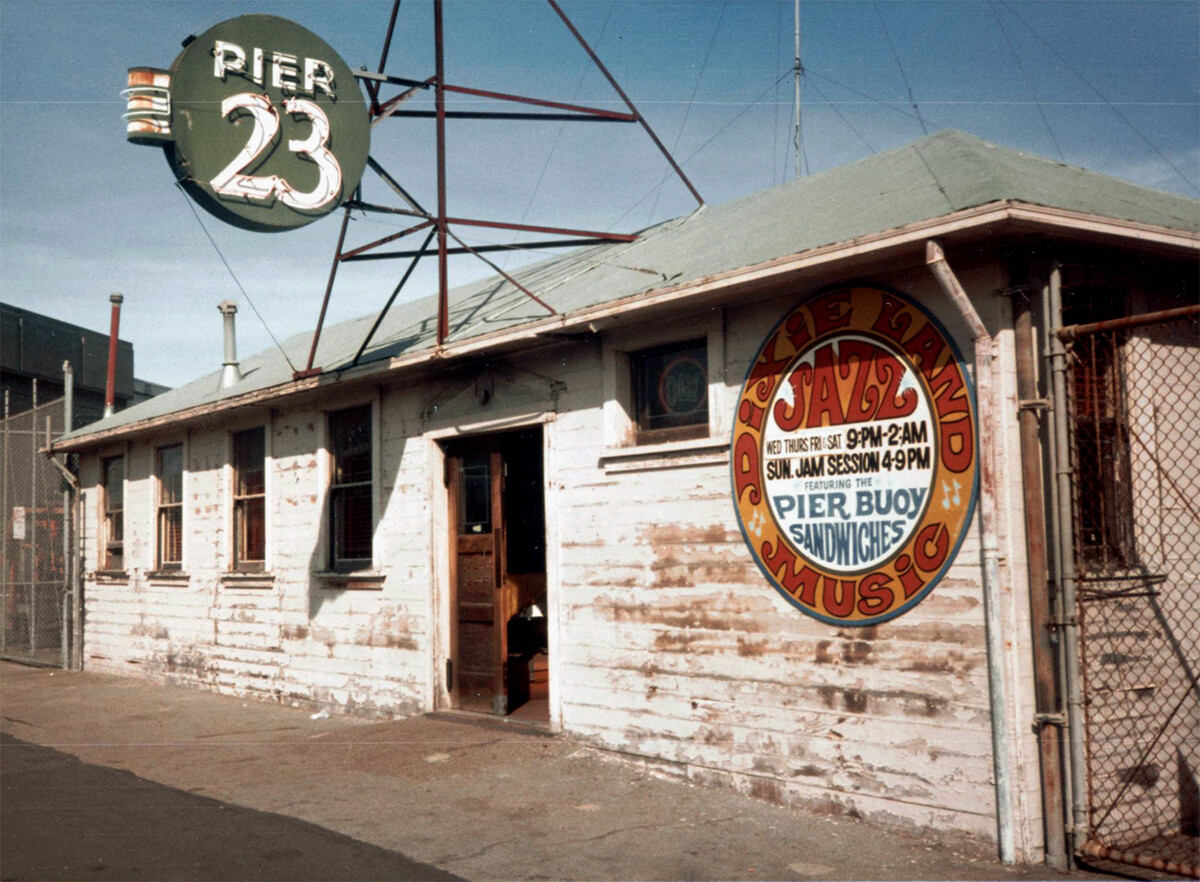

He also described a run-in with Kid Ory. In the late 1950s, Burt played regularly at Pier 23, on the Embarcadero in San Francisco—across the way from Ory’s On The Levee nightclub. At the Pier, there were often enough musicians sitting in to make up several full-size bands. And the sales of ltiquor, beer and wine were incredible. On The Levee was run according to musicians’ union rules. The sextet was paid union scale and no sitting in was allowed. One night during an intermission at the Pier, Burt wandered over to On The Levee to hear Ory’s band. Upon entering, he immediately noticed the sparse crowd; a glaring contrast to the capacity audience at Pier 23. Kid Ory saw Burt walk in the front door, put down his horn and rushed towards Burt with fists flailing. The much taller pianist managed to flatten his palm on Ory’s forehead and keep him at arm’s length. He restrained the trombonist, calmly repeating, “Now, Ed. Now, Ed…”

On several occasions, I got to visit with Burt at his apartment. He was extremely generous, loaning me rare acetates (duets with Bill Dart, an audition for a radio program called Tempo Train, featuring Clancy Hayes), original prints of Bunk Johnson and Benny Strickler, numerous professional photos of Burt himself and a letter from Bunk, asking Burt to mail him a carton of Kool cigarettes!

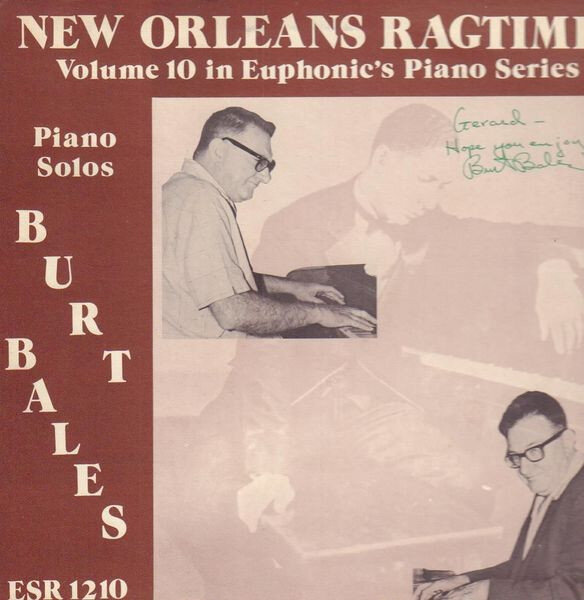

During one visit Burt said that in the late 1940s, Jelly Roll Morton’s sister Amède Colas heard him play and was so taken with his interpretations of Morton’s music that she gave him some rare snapshots of her brother. Burt dug them out of a trunk and handed them to me, saying “I know you’ll appreciate these.” (I did, but unwisely loaned them out—with predictable results). Another time, my mother was visiting and came to Vic’s to hear the band. As usual, Burt sang and after the gig we drove him back to his apartment. My mom told Burt how much she enjoyed his piano playing, from the first time she heard the After Hours record. When we arrived at Burt’s apartment, he said, “Wait a minute.” He disappeared inside the apartment, but quickly emerged with a copy of his Euphonic LP New Orleans Ragtime. He handed it to my mom, saying “For you. Hope you enjoy it.” I will never forget the surprised and delighted expression on my mom’s face!

During one visit Burt said that in the late 1940s, Jelly Roll Morton’s sister Amède Colas heard him play and was so taken with his interpretations of Morton’s music that she gave him some rare snapshots of her brother. Burt dug them out of a trunk and handed them to me, saying “I know you’ll appreciate these.” (I did, but unwisely loaned them out—with predictable results). Another time, my mother was visiting and came to Vic’s to hear the band. As usual, Burt sang and after the gig we drove him back to his apartment. My mom told Burt how much she enjoyed his piano playing, from the first time she heard the After Hours record. When we arrived at Burt’s apartment, he said, “Wait a minute.” He disappeared inside the apartment, but quickly emerged with a copy of his Euphonic LP New Orleans Ragtime. He handed it to my mom, saying “For you. Hope you enjoy it.” I will never forget the surprised and delighted expression on my mom’s face!

A few months later, Burt invited me to listen to some unissued recordings. He was hoping to find a producer who would release them on an LP. When he played the tape, I was surprised to hear a swing trio. Besides Burt, there was Vince Cattolica—a great clarinetist—and hard-driving drummer “Cuz” Cosineau. There were some parallels to the Benny Goodman Trio, but the individual voices of Cattolica, Cosineau, and Burt were unmistakable. I wish that session had been issued.

Burt played quite a bit of post-1920s music at the Washington Square Bar & Grill. One night, two young guitarists and a bassist were sitting in. I happened to have my snare and hi-hat along, so I joined in. Burt asked each musician which song they would like to play. The others asked for “You’ve Changed,” “All The Things You Are,” and “There Will Never Be Another You.” I requested “Old Fashioned Love.” Burt spun around on the bench: “JIMMY JOHNSON’S ‘Old Fashioned Love’?” (Later I found out that Burt was acquainted with James P. Johnson. They performed on a concert in Pasadena in 1949; Burt with Turk Murphy’s Bay City Stompers and James P. in a trio with Albert Nicholas and Zutty Singleton. On the last song, the trio joined Turk’s band onstage. Burt sat side-by-side on the bench with the “Father of Stride Piano”)!

Burt played quite a bit of post-1920s music at the Washington Square Bar & Grill. One night, two young guitarists and a bassist were sitting in. I happened to have my snare and hi-hat along, so I joined in. Burt asked each musician which song they would like to play. The others asked for “You’ve Changed,” “All The Things You Are,” and “There Will Never Be Another You.” I requested “Old Fashioned Love.” Burt spun around on the bench: “JIMMY JOHNSON’S ‘Old Fashioned Love’?” (Later I found out that Burt was acquainted with James P. Johnson. They performed on a concert in Pasadena in 1949; Burt with Turk Murphy’s Bay City Stompers and James P. in a trio with Albert Nicholas and Zutty Singleton. On the last song, the trio joined Turk’s band onstage. Burt sat side-by-side on the bench with the “Father of Stride Piano”)!

After moving to Cincinnati in 1980, I lost touch with Burt for a few months. Then, one day he called to say that he had received a gift of a cross-country bus ticket and he intended to use it for visiting friends. June and I were delighted to have Burt stay with us and his visit came at an opportune time: Terry Waldo’s Gutbucket Syncopators were booked for a series of gigs in the area. Burt came to the GBS appearance at Arnold’s in downtown Cincinnati. He played two solo intermissions, including a great “Spanish Tinge” interpretation of “Temptation Rag”—very close to the version he recorded for Good Time Jazz in 1949. He also sat in with the band and everyone loved hearing the powerful, rolling bass lines in his left hand and the agile, Morton-inspired right hand. As if one distinguished guest was not enough for the musicians and the audience, blues singer Claire Austin—then living in Cincinnati—showed up to sing with Burt and the band! The Syncopators were thrilled to hear and perform alongside Burt. It was obvious that he was enjoying the “celebrity status” and his very full sound on the piano had not diminished at all.

The last time I saw Burt was in 1989, when he came to New Orleans. He was no longer playing, but wanted to hear bands and meet with musicians and fans. He was particularly impressed with pianists Steve Pistorius and David Boeddinghaus and enjoyed visiting with George H. Buck Jr. and Barry Martyn. Burt was obviously in ill health during this trip, but his condition was even worse than he let on. He passed away shortly after returning to San Francisco.

Burt Bales’ solo and band recordings are still among my favorites. And it always brings a smile to my face when I hear Burt’s influence on the two pianists who best understood his music: Ray Skjelbred and Steve Pistorius.

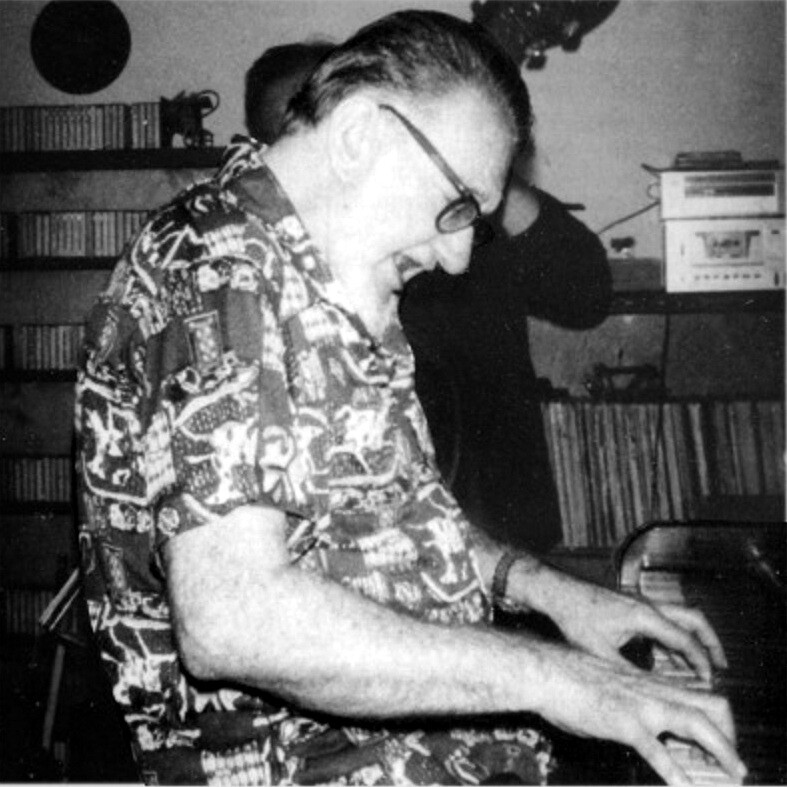

Otherwise, I like to remember Burt in happier days—such as the first time I heard him play a solo gig at the Washington Square Bar & Grill. He walked in from the cool, damp, foggy weather in a long overcoat and a beret, leaning heavily on his cane. He was several pounds heavier than in 1973 and had grown a substantial white beard. He hung up the overcoat and beret, revealing a very bright Hawaiian shirt. Burt seated himself on the piano bench, blew his nose lustily into a threadbare bandanna, rasped “Heh-heh-heh” and rubbed his hands vigorously. Then he launched into his signature opening song: “I’ve Got A Feeling I’m Falling.” The music that followed was every bit as exhilarating as the solos on that old After Hours 10-inch LP.

Hal Smith is an Arkansas-based drummer and writer. He leads the El Dorado Jazz Band and the

Mortonia Seven and works with a variety of jazz and swing bands. Visit him online at

halsmithmusic.com