The End of the Ragtime Revival?

To the Editor:

I am writing in reference to “Max Morath and the 1941-2023 Ragtime Revival,” published in the August 2023 issue of The Syncopated Times. With all due respect, I wish to dispute the following points:

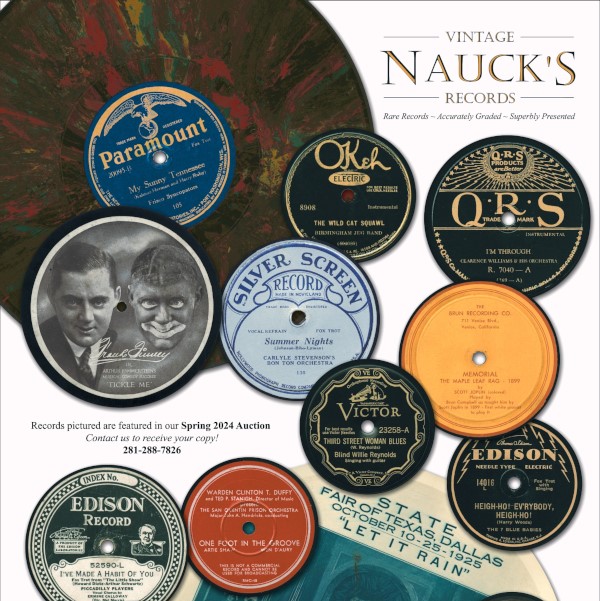

Firstly, the author of said article choosing 1941 as the date of the “ragtime revival” is arbitrary. This is because there are examples too numerous to completely enumerate of recordings of rags made before that date. For example, Maple Leaf Rag was recorded many times after Joplin’s death, e.g., by The New Orleans Rhythm Kings in 1923, by Sidney Bechet and his New Orleans Footwarmers on September 15, 1932, by the Halfway House Orchestra on September 25, 1925, etc.

Novelty piano rags were recorded incessantly throughout the 1920s. Arthur Schutt recorded Bringup Breakdown in 1934. Frank Herbin recorded Peanut Cackle that same year. Bob Zurke recorded Hobson Street Blues in 1939. I’m too lazy to provide other examples. Why not 1959, the year that Joe Lamb recorded for Folkways Records? Or 1966, the year that Rudi Blesh produced They All Play[ed] Ragtime for Jazzology? Or 1950, when TAPR was first published in book form? I therefore submit that 1941 as a date when ragtime was just magically “rediscovered” is demonstrably not true, because in one form or another, ragtime was constantly being played and recorded throughout the 20th Century, regardless of popularity or sales.

Secondly, paragraph three states that Max wanted to play ragtime as a full-time profession. While I was not alive in the 1940s, ’50s, or early ’60s, I knew Max for almost 44 years and at no time does this sound like the Max I knew. In fact, for as long as I knew him, Max never spoke or wrote of being interested in Ragtime, per se, but rather, in music. Every time we spoke, we spoke of music rather than ragtime. Ragtime was only a part of what made him tick. He was a profoundly educated and cultured individual. For instance, Max knew hundreds, perhaps thousands of vocal songs, and didn’t just play them publicly to make money, but because he had a general interest in American culture from the 1890s to the early 1920s.

In an interview with John Edward Hasse on September 26, 1977, (Ragtime: Its History, Composers, and Music, ed., Hasse, Schirmer Books, 1985, pp. 188 – 193) Max stated that his playing until his early thirties was largely improvisational, which would preclude the definition of ragtime which most white people in North America in the 1960s and ’70s would have [please see my interview with William Bolcom in TST about how black people in America tended to be more improvisational in their ragtime interpretations]. Max further stated that one of the main reasons he didn’t perform music from the 1920s was not because of any supposed notion of “authenticity” (something in which Max stated he was not really interested) but because one would need a band to have any real sense of “fun” doing so. Although Max did go on to record songs by composers like Rodgers and Hart with William Bolcom and Joan Morris.

Finally, he discussed with Hasse how members of the audience would come up to him sometimes after one of his shows, and say, “Well, gee, we liked the show, but you only played six or seven rags. We thought you’d play all the Joplin Rags.” And Max would respond, “Well, I hate to disappoint you, but I have never done that.” Max goes on to say to Hasse, “And I never have.” [emphasis on the word “never” is mine]. My recollections and Max’s own words appear (in writing) to negate the author’s assertion.

Thirdly, the author mentions the “national [ragtime] craze” brought about by the film, The Sting, but not who benefited. Who did benefit? Not Scott Joplin; he was long dead. His familial descendants never earned a penny from his music. What serious money did appear to be made either went into the pockets of wealthy white people who arranged or produced recordings of his work, or was fought over in litigation by those overseeing the Lottie Joplin Thomas Trust and Vera Lawrence. As Edward Berlin states intelligently in his book, King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and his Era (OUP, 2nd Edition, 2016, p. 334), “The winners in this episode were clearly the lawyers.” Personally, I’d be very wary of any fad or craze because people have a tendency to become focused on money rather than quality or artistic integrity.

Fourthly, in the 9th paragraph, the author states that Max’s death “symbolizes the end of the ragtime revival.” Seriously, once again what does this arbitrary statement even mean? Why not choose the date where Max stopped publicly playing the piano (he semi-retired about 15 years before he died). And how does Max’s passing bring about the music’s “revival” to a close?

Ed Berlin is still publishing articles in TST and elsewhere, and enlightening us with new information about ragtime’s often murky past. Jeff Barnhart is still playing ragtime publicly and bringing it to the public’s attention in his inimitable witty fashion. Newer and younger performers such as Christina Pepper and Stephanie Trick are playing ragtime publicly and putting videos on YT, bringing “new blood” to the ragtime world. I understand that Reginald Robinson is making a documentary about the music. R.S. Baker brings us historical articles about ragtime’s obscure figures once a month in TST. Galen Wilkes is continuing to do public lectures and putting together his copious research on ragtime history for future generations. Peter Lundberg just uploaded an album he recorded to YouTube. All music is now being propagated by social media as much as by live performances.

Finally, TST miraculously appears once a month with Andy Senior (remember him?) bending over backwards (not to mention other cirque du soleil gyrations) to fill up 40 pages every 30 days and keep ragtime and early jazz in our faces and help keep the music alive. With all due respect to Max and his memory, the musical movement he helped create demonstrably did not stop with either his retirement nor his death.

Fifthly. in the 10th paragraph, the author asserts that “there is practically no published ragtime commercially available.” What?!? This is nonsense. Go to the Dover publications website, input the word “ragtime” and you’ll see several folios show up. The difference is that many publishers now use e-books instead of paper copies. Go to ebay.com, or alibris.com, or thriftbooks.com and you’ll find all the old Dover publications by Tichenor, Jasen, Blesh, et. al, just waiting for someone to buy them. Buying new books is bad for the environment, anyway. Even if those books were still in print, I’d buy second-hand copies.

While I’m not a big fan of supporting Jeff Bezos, if you go to Amazon and type in “ragtime sheet music,” you’ll come up with 51 pages of the stuff. Go to the JW Pepper Site (tinyurl.com/jwpepperragtime). Go to Ragsrag.com and you’ll find over a hundred obscure early rags transcribed from piano rolls. In addition, both the Library of Congress and imslp.org have more early ragtime sheet music for FREE than you can shake a stick at.

This is just the tip of the iceberg. If I had had all these options of buying or downloading free early ragtime when I first became interested in the 1970s, I think it would have blown my mind. There is infinitely more variety of pre-1924 vintage music available now than ever before. The author’s statement is categorically false on every level.

Sixthly, the above and other statements smack of a hankering for “The Good Old Days.” Let us read Max’s own words about what he thought about the “The Good Old Days” (from AMNY The Villager, posted February 10, 2004, tinyurl.com/maxmorath2004: “People talk about the good old days, but I don’t think there is such a thing…If it’s my good old days, we’re talking about the Depression. My folks separated when I was four. I don’t know how my mother did it…” Max always gave me the impression of being allergic to “nostalgia,” for that and other reasons. Jazz history can so often wind up becoming romanticized or at least, inaccurate. By writing this letter, I am attempting to “nip that in the bud.”

And lastly, Max and I did not see eye-to-eye about everything, but if you could sum up his attitude, it might be “a consummate professional.” Publicly he aspired to being completely positive. I’m not claiming to be a medium or to be able to read minds, but I think that Max would have been very uncomfortable about anyone using his passing as a means to propagate an agenda—particularly one that was not his own (and BTW, Max never had one!).

Further, if by some miracle, he was still able to communicate with us, he might have said something like, “Yeah, I know I’m not here anymore, but it’s time to move forward. Use the musical gifts I gave you and pass them on to as many as possible, because it’s the music that’s important.” Max was most definitely not into personalities or anything resembling cultism. His whole life, work, music, and ethos was designed to delight, never to denigrate.

Let’s try and honor his memory and legacy by being positive, and not tearing things down. Because Max, despite him being a metaphorically towering figure, was humble and honest, and for him the music was more important than anyone’s ego. Even his own.

Matthew de Lacey Davidson

Halifax, Nova Scotia

Jean Goldkette: Setting the Record Straight

To the Editor:

The August 2023 issue of The Syncopated Times includes the article “Jean Goldkette and Roger Wolfe Kahn” by Scott Yanow. We quote from the article: “Oddly enough, the final jazz number released as by the Jean Goldkette Orchestra (July 27, 1929) was actually performed by the nucleus of McKinney’s Cotton Pickers because the Goldkette band’s bus broke down on the way to the studio and they were unable to make it.”

In a two-part article published in 2011 in VJM Magazine, “Jean Goldkette’s Post-Bix Recordings: the Don Redman Arrangements,” we presented conclusive evidence that the July 27, 1929, recording of “Birmingham Bertha” as well as several 1928 Goldkette recordings were recorded in Chicago by the full Jean Goldkette orchestra. The only association with McKinney’s Cotton Pickers was the fact that the Goldkette orchestra was using arrangements by Don Redman, who had also rehearsed the band in Chicago, where it was based at the time.

Specifically, we refer you to Part Two of our article, which can be accessed online here: www.vjm.biz/160-goldkette.pdf.

On page 16, under the heading “Birmingham Bertha” (right hand column) we outline, in considerable detail, the circumstances surrounding the recording of “Birmingham Bertha” by the Jean Goldkette orchestra. The evidence for the recording being by the Jean Goldkette orchestra—as listed in the Victor recording files and on the record label itself—is overwhelming, and is backed by verifiable historical documentation and a careful aural analysis of the recording itself, both by the authors and by a number of experts (listed in the references at the end of our article), including professional musicians with extensive knowledge of the Goldkette band’s arangements.

Considering our research work here, and the conclusions reached after such a careful and rigorous analysis of the facts, we feel that a mention of our conclusions should appear in the next available edition of your excellent publication.

Should you require any further clarification or help on any points, please contact one of the authors, contact details for which are provided below.

Albert Haim,

Nick Dellow