My contemporaries and I at Chiswick County Grammar School for Boys heard our first jazz records in one of a row of four World War Two air raid shelters still on the edge of the school playing field in 1948, when I was fifteen. These large ready-made concrete-lined grottos, ten feet below ground but with a six-feet high mound of earth on top of them were officially out of bounds but readily and secretly available for liberation by anyone with the nous to substitute the heavy government-issue padlock barring entry with a similar one of their own. I was shaken rigid when one of the teachers, by the funny name of Charley Garlic, stopped me in the school corridor and said, pointing to my large suit-case, “Don’t think that we don’t know what you’ve got in that case, Stanners!” However, the powers that be never did find our camp!

The shelters of which all had proved their need because we had two bombs on the school buildings and one V1 “Doodle Bug” on the school field, when fortunately the school had been evacuated to High Wycombe. These spacey “hidey hole” shelters were full of rubbish but by sweeping this to one side, the judicious acquisition of six chairs and a couple of ammo boxes and lighting the dank gloom with a candle in a jar, there was soon ample palatable room to house a wind-up gramophone transported in a large suit case (obviously originally mysterious to some of the Teachers!) together with a dozen 78rpm records. Both these latter ingredients were borrowed from one of our group’s benevolent uncles whose choice of records, the Dixieland of Sid Phillips, Harry Gold and his Pieces of Eight, Joe Daniels and his Hot Shots, and Tommy Dorsey’s Clambake Seven, while not strictly PC, gave us a healthy introduction to two-beat jazz.

This musical bias was adjusted when we joined the Cranford Jazz Club, featuring the Crane River Jazz Band, in December 1950, when my membership number, 992, was just eight short of winning me a free ticket to the jazz concert at the Festival Hall to celebrate the Festival of Britain in 1951. By the time we joined the club, Ken Colyer had officially departed the Cranes to join the embryonic cooperative band “The Christie Brothers Stompers” with Ian and Keith Christie, late of Humphrey Lyttelton’s band, leaving the Cranes in the capable hands of the original second trumpeter, Sonny Morris. However, we still spent that momentous first Friday evening in total bliss in a large corrugated iron hut on the banks of the River Crane in the grounds of the White Hart pub in Cranford being transported back to the nearest thing we knew to New Orleans.

That very evening “instant icing” was added to the cake when Ken walked in half an hour into the first session to become primus inter pares fronting the band. It was to be almost five years when I heard, on record, the feather-light lilting and lifting drive of Sam Morgan’s rhythm section, before I realised that the Cranes’ somewhat plodding beat was not quite as authentic as we had previously thought. Even so, subject to the National Service demands of the Army and Royal Air Force in my case, for almost a decade Friday nights were to be reserved for the Cranes. The musical fare featured was a healthy diet of New Orleans favourites rather than the classical output of the Oliver and Armstrong bands of the twenties but with sessions always ending at 11pm with a rollicking rendition of “Get Out of Here and Go on Home” and the inevitable hurtle across the road to catch the last number 91 bus to Chiswick.

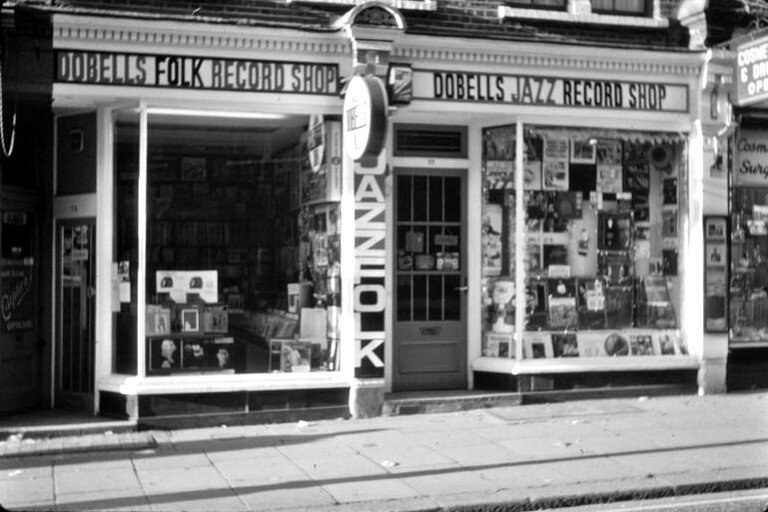

At the beginning of the fifties there were three specialist jazz record shops in Charing Cross Road. Of these, Dobell’s, at No.77, later to be associated with the iconic 77 label, was the most important. When I first went into that shop, the sign above the front read something like “A. & D. Dobell Antiquarian Book Sellers,” Here Doug Dobell, founder Arthur’s son, had a cardboard box at one end of the counter with very few 78rpm records for sale. The first record I bought there, “truistically” dictated by what was available, was a 78rpm of ragtime pianist Lee Stafford playing “Winter Garden Rag” and “Heliotrope Bouquet” and I still have one of the books I bought there at that time, Plays Pleasant and Unpleasant by G.B. Shaw. Almost opposite Dobell’s was The International Bookshop and there, in a record section housed in the basement, Al Fairweather and Sandy Brown often held sway. There was also a shop on the first floor of a building just beyond Cambridge Circus, named after a record label, possibly Vocalion and a year or so later James Asman set up in New Row, off St. Martin’s Lane.

From then on, although for some of us our Saturday afternoons were reserved for sport, for all of our gang, Saturday mornings were spent in London’s version of the “French Quarter” in search of elusive records which were mostly imported from the States.

The late hours into early Sunday would be spent in one or other of our bedrooms listening to our collections including new acquisitions. Deviations from the straight and narrow, such as the penchant of one of us for Bix, were just about tolerated. This midnight get together could also involve blindfold tests when new acquisitions would be proudly rolled out. On these occasions my method of confounding and annoying interrogators was to identify principal instrumentalists, trumpeters, clarinetists, trombonists, and pianists whose sound would, one hoped, reveal their identity. I could then identify the band but keep that information to myself. Then, seemingly out of the blue, I would say, “That’s Pops Foster on bass, Johnny St. Cyr on banjo, Andrew Hillaire on drums etc, etc..!”

Forfeits were quite commonly demanded for any misdemeanour that incurred the wrath of fellow burners of midnight oil and these penalties might be incurred by introducing recordings of jazz music off the straight and politically narrow path into our late night sessions. The favourite punishment, which acquired semi-mythical status because it was well nigh impossible to achieve, as the ingredients were highly unlikely to be available, was to recite Stan Kenton’s discography backwards with a mouth full of cream crackers! The line was finally drawn under one particular gang member when he put on a 78 which began with a little voice saying, “See ya lader Alligader!”

In those early days a slight and occasional diversion from the straight if not narrow Charing Cross Road into Covent Garden would take us to Paxman’s, a shop primarily selling musical instrument cases. There an off-beat treat awaited us. Stationed on the half landing of the two flights of stairs leading to the basement of this out of the way shop was the huge double-bass tuba originally made for John Philip Sousa’s Orchestra. It towered majestically on its purpose-built timber wheeled stand. There we could indulge the surreal temptation of being able to blow a very low and raucous note akin to the noise made by the Royal Mail Steamer, Queen Mary entering Southampton docks which was always too much to resist.

By the mid-fifties I’d got a new job with Wandsworth Borough Council which entailed pounding the streets. Since the borough boundaries stretched further than they do now, I became acquainted with drummer Dave Carey’s shop opposite St. Leonards Church at the junction of Streatham High Street with Streatham Hill. However, in seven years or so the number of jazz record shops I knew of had still only swelled to six. This meant that the Musicians Union’s wrong headed protectionist policy barring entry into Britain to all American musicians not only deprived us of hearing the best musicians live, but the early jazz records we coveted continued to be as rare as hen’s teeth or even the mythical Buddy Bolden cylinder which we pursued like explorers seeking the legendary unicorn.

At about this time the acquisition of a booklet which could be rolled up to fit in a mackintosh pocket, The Junk Shoppers’ Guide, completed the circle for me. While officially on my rounds out of the office, I could still patrol Balham High Road and the appropriately named Upper Tooting Road, with their half-dozen shops devoted to house clearance, to sift through the piles of 78s on offer outside them for a tempting six old pence each. Most of these records were of no interest, but the real names of some of the great bands concealed beneath pseudonyms designed to avoid contractual difficulties were revealed within the carefully researched pages of this booklet and were sometimes worth hearing. Also, while some of the music did not strictly adhere to our purist policy, it was occasionally worth ploughing through the welter of what we called “musical sludge” to uncover gems of solos by great jazzmen, some of them known colloquially as “visiting firemen,” hot jazz instrumentalists earning their keep with big bands. This information was helpfully listed in the guide and its results gratefully listened to, through typical snap, crackle, and pop, when located.

The paucity of detailed information in this piece regarding the travails of record collecting in this era reflects the scarcity of records available in the specialised area in which we were collecting. Our quest was like hunting big game in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean! I particularly remember this feeling of deprivation was considerably heightened when we found that high on the list of our home grown hero, Ken Colyer’s favourite bands was the Jones and Collins Astoria Hot Eight, whose late twenties recordings I believe he acquired while on his visit to the States and in particular New Orleans in 1953.

However, suffice it to say that there was a grape vine which on one occasion directed me to St. John’s Wood where I was able to buy an acetate 78rpm record of the Yerba Buena Band playing “Milenberg Joys” and “Smokey Mokes.” Nonetheless, this was one of my few successful forays away from our usual hunting grounds in Charing Cross Road and I distinctly recall the doubly guilty feeling I experienced, firstly because the Lu Watters’ band was a white revival band and the record was on acetate which, being illegal, as were pirated recordings, had previously been taboo and not countenanced or purchased by our gang.

The sudden change in the attitude of collectors and of our gang in particular to what we had previously seen as an infringement of the rights of American musicians and therefore off-limits, namely acetates, was enabled by the introduction of these pressings on wax discs with an alloy core to his stock by Doug Dobell. Because we felt that Doug, otherwise the epitome of rectitude, must disagree with the stance of the UK Musicians Union, this immediately legitimised a source of recorded material which had previously been out of bounds. The availability of acetates meant that we would at last have access eventually to the New Orleans bands of the so-called revival, those of Bunk Johnson and George Lewis being at the forefront and other much coveted American Music 12” LPs.

However, these bands were not to be the first acetate which went onto my Garrard turntable which played through a large family radio. I make a slight detour to say that an early danger to record surfaces came from the music being played: An explosive and rumbling Baby Dodds drum break could lift lightweight pick-up arms off the surface of 33&1/3 rpm and 45 rpm tracks and send them skidding across records. To counteract this, one of our gang from the school science 6th form invented the simple remedy of attaching an old penny on top of the pick-up head which just kept the needle in the groove without being heavy enough to damage it!

Now, with the few early jazz LPs in the shops, the first to grace my shelves was a real cross section of bands recorded in the twenties titled New Orleans Horns featuring tracks by Oliver’s Creole Band, the little known Charles A. Matson’s Creole Serenaders, Keppard’s Jazz Cardinals, and Bernie Young. My first long play acetate bought from Dobells betrayed the beguiling and possibly misleading attractions of this system of collecting: You could listen to a recording in a sound-proof booth, select and order certain tracks from any LP and collect what might be a mix of the output of the sessions of two or more different bands engineered, I recollect by John R.T. Davies of the Cranes and later the Temperance Seven, a week later. This would give you a ten inch long playing record with four of Oliver’s previously unobtainable Creole Band tracks on one side and four Sam Morgan tracks on the other, simply because no other tracks were available from either band.

The Morgan recordings in particular brought this fabled early New Orleans music up to date by introducing us to those who were to become side-men of Bunk Johnson’s and George Lewis’s revival bands, trombonist Jim Robinson, bass player Sydney Brown and pianist Walter Decou. Pianist Joe Robichaux and banjoist Emanuel Sayles of the Jones and Collins Astoria Hot Eight were also active in the revival and all joined Baby Dodds in connecting the late thirties and early forties Revival to the New Orleans and classical recordings of the twenties. In the process it was delightful to find that Big Jim’s latter day Walt Whitman-style “Blues shouting trombone,” as featured particularly in his duet with George Lewis on “Ice Cream” could “Roar you as gently as any sucking dove” as in his solo on “Short Dress Gal” with Sam Morgan in the late twenties.

Dobell’s soon had a second hand department in the basement of No. 77 where lively conversation and livelier arguments could be had with Bill Colyer, Ken’s brother who could be behind the counter. Bill played wash board in Ken’s skiffle group but, unlike those fully paid up American drummers such as Baby Dodds and Jimmy Bertrand who played this space saving alternative percussion instrument with it clenched tightly between their knees upright at Rent Parties, Bill played his washboard flat on his knees. Hence, having failed to raise the £10 I needed to buy a double bass, (in 1954 my salary was £350 per annum) I took up the washboard and copied Bill’s method in the small and short-lived band we formed. An amusing spin-off from this time came when I was walking home from a gig at 1am carrying my “instrument” in a brown paper parcel and was stopped by the “law” in a car. My answer to a question as to the contents of my package, together with a stumbling explanation, brought hoots of laughter and, from the driver as he pulled away, a further query, “Do you play the musical saw as well?”

The wheel had come full circle by the time I got a job for the London County Council at County Hall in 1959. Not only did it put me within easy lunch-time reach of Charing Cross Road via a brisk walk over Hungerford Bridge, but it introduced me to one of the best street markets in London, colloquially known as The Cut although its street name was Lower Marsh. This consisted of about two hundred yards of costermongers’ carts on both sides of the road, mostly comprising stalls selling fruit and vegetables but also catering for almost any item of food and small kitchen utensils. One astute trader had managed to acquire, I think from the States, remaindered 12” jazz LPs which enabled me to add a dozen records which succeeded in filling in gaps in my collection, at a mouth watering five shillings each.

The ultimate product of this decade of fruitful endeavour was the numbers of self-taught musicians who emerged from our activities. The most pre-eminent of these who was in my class at school became one of the best banjoists in the country, still playing today. Being a natural musician he taught himself to play ragtime piano and in band change rounds would play trombone. He was also musically literate enough to be able to write out ragtime chord sequences for Ken Colyer to arrange for his band. I would accompany him up to The Tartan Dive in Great Newport Street off Charing Cross Road where, being aware of Ken’s dislike of hangers-on invading his territory, I would steer clear at the other end of the bar while their business was transacted.

Another of our gang who himself played semi- professionally briefly, has a younger brother, a trombonist who has run his own band successfully for over thirty years and the younger brother of one of my girl friends whom I introduced to both early jazz and classical music, played with Steve Lane’s Southern Stompers before going up to Cambridge University and on to the States to take on a professorial role at Harvard University. One of us even moved up a gear to play his trombone in mainstream groups, latterly in the south west.

Despite this period of slightly more fruitful harvesting of records being slowed down by the onset of marriage and temporary penury, the cement which held our jazz world together continued to be Dobell’s which by now, in the early sixties, could advertise to the effect that, “True Jazz Lovers are Those Born within the Sound of Dobells.”

Even then, although I was nowhere near getting my hands on the Alan Lomax Library of Congress recordings of conversations with Jelly Roll Morton or even Morton’s, Oliver’s, and Armstrong’s complete recordings of the twenties, No. 77, Charing Cross Road was still the honey-pot around which we hovered. On one frustrating occasion one of Doug Dobell’s senior assistants even offered to lend me reel to reel tapes of the Lomax Morton interviews for me to tape my own copies but I had neither the means or money to take up his fabulous offer and had to pass on this golden opportunity which remained un-remedied for at least five years.

Through the years I could still buy books on jazz at Dobells, on one particular occasion experiencing a pleasing built-in surprise: that was the day when Doug Dobell was telling me that he had no copies of a book I wanted to add to my shelves when he looked over my shoulder as the shop door opened and said, “Morning John, have you got any copies of your new book?” and, as a result of that most serendipitous encounter, I triumphantly marched off with my latest purchase, a pristine copy of John Chilton’s Who’s Who of Jazz signed by the author.

David Stanners is a life-long jazz fan living in the UK.