Introduction

Blues singer Gertrude “Ma” Rainey (née Pridgett) was born on April 26, 1886, in Columbus, Georgia, and died there on December 22, 1939.1 Advertising in the 1920s frequently billed her as “The Mother of the Blues.” And while there may be occasional conflicting information regarding some basic facts concerning her life, there is a general consensus amongst most articles and books that she was a dynamic performer, influential as a songwriter, and a musical innovator.

It is the last two of these attributes which will be the subject of this effort. Sadly, in our celebrity and personality obsessed culture, too much attention is often paid to either the behaviours or characters of public figures. This is unfortunate, as it distracts us from what is truly important about artists (in this particular case, the music). However, in order to understand in what ways Rainey was innovative, one does need to delve a little into biographical information.

Early Years

Rainey was the second of five children and has been occasionally confused with a sister by the name of Malissa. Both her parents came from Alabama, and there is a possibility that one of her grandmothers may have performed on the stage soon after Emancipation. One of Rainey’s first public appearances was at the age of fourteen (around 1900) in the Bunch of Blackberries review. She went on to perform in tent shows and later reported adding “blues” songs to her repertoire as early as 1902. In the late 1930s, she stated to musicologist and Professor John Wesley Work, Jr. of Fisk University that she sang “blues songs” as early as 1905.2

In 1904, at the age of eighteen, she married William “Pa” Rainey, an entertainer some years older than her. They became a song-and-dance act, with “Pa” doing comedy as well, working in black tent shows and minstrelsy.3

Minstrel shows were traditionally racist representations of black people depicted by white performers with “comic” stereotypical views of black people and presented as an “entertainment.” Sadly, many prominent black artists of the time were well known for working in this arena of the entertainment industry, for instance, Bert Williams (who was the first black American to star in a film).4 Jewish performers (such as Sophie Tucker) were sometimes expected to perform in “blackface” as well.5

The shows in which Rainey mostly travelled, usually toured throughout the American South, and, more often that not, finished in New Orleans. It is in this location that she would have met many prominent jazz artists of the time, such as Joe Oliver, Sidney Bechet, and Louis Armstrong. The time in which she was performing also coincided with the era when the term “blues” was used, often and conspicuously, in the sheet music industry (at least, in larger cities). This was despite whether the music bore any relation to real blues singing. Blues singing would have been experienced more in person from tent shows outside of cosmopolitan areas in the U.S.6

Vaudeville Performances

Prior to 1921, apart from singing, Rainey also would have performed comedy, dancing, topical songs, and the latest paper “ballits” (which were song sheets from the city). She was usually accompanied by a small jug band, a pianist, or a small jazz combo,7 but her earliest accompanying groups would have consisted of drums, violin, bass, and trumpet.8 Apparently, early on Rainey’s career, it was expected of the performer to follow the written musical score as closely as possible. However, Rainey was one of the first to break away from the “written note.”9

According to an account of around 1917,10 one of Rainey’s performances took place in a huge tent, bigger than a medium-sized theater. This seems to be corroborated by an advertisement of Ma Rainey performing with the Alabama Minstrels of around the mid-1920s. It depicts the kind of tent one might associate with a major event such as a large Circus.11 12 Although both black and white people attended the performance, the audience was segregated with black people sitting to the left, and white people sitting to the right. Apparently, Ma Rainey was popular amongst white audiences, as well as black, even in the American South, as shown by the fact that most of the tent shows in Jackson, Mississippi which included Rainey were for white people only.13

Her shows might invariably start with an opening instrumental number, followed by flashing lights and a rising curtain, and a chorus of young men and women singing a song (such as Strut Miss Lizzie). The women usually wore ostentatious costumes. A comedy skit would usually follow, which might include broad ethnic humour. Then a young woman singer (a “soubrette”) would sing a fast dance number (such as Ballin’ the Jack). The chorus might reappear at that point to dance the song with her. Second to last would be another comedy act again, followed by the entrance of Ma Rainey. She would usually start by telling jokes about her craving for young men, and then sing several songs (such as Jelly Roll Blues, or I Ain’t Got Nobody). She usually ended the show with her singing something like See See Rider, knowing that this would bring the house down (she would record it years later with Louis Armstrong). After Rainey’s solo performance, the entire ensemble would join her on stage for a finale of singing and dancing.14

Musical Influences

While Ma Rainey’s influence on other blues singers might be musically implicit, much has been journalistically made of her association with the “Empress of the Blues,” Bessie Smith. And although there is no proof that Rainey actually “kidnapped” Smith (Rainey, to the best of our knowledge, never kidnapped anybody!), they were certainly on friendly terms, even if they weren’t close friends. They most likely met sometime between 1912 and 1916, when Bessie Smith was starting off as a dancer in a travelling show in which they were both employed.15

However, Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey could not have been more different as both artists and individuals: quite literally chalk and cheese. Smith was fond of hard drinking and physical fights. On the other hand, Ma Rainey, by many accounts, did not allow drinking in her shows and behaved thoughtfully and professionally.16

In terms of technical accomplishment and musical style, from those who heard both Bessie Smith & Rainey live, most agreed that while Smith had the better voice (and one which may possibly have recorded better, as well), Rainey had a much better rapport with the audience, was a better all-round performer, and was described as, “…a person of the folk…very simple and direct.”17

On August 10, 1920, Mamie Smith (no relation to Bessie) recorded the first genuine blues record, was the first black American to do so, and the first black woman to record. She was 29 years old at the time. It was not her first recording for the Okeh label, but it apparently sold spectacularly well, and established an extraordinary market for black American music throughout the 1920s, much of which would be released on a number of different labels, featuring numerous artists.18 19

Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey would start recording approximately three years later, Bessie when she was 29, and Ma Rainey when she was 37, a good eight years older.20

Recording with Paramount Records

It is not known why Rainey recorded with the Paramount label. It could be that that was the only offer she received. However, Paramount was the predominant label selling “race records” (an industry name for the market of records of music performed by black musicians) from 1923 to 1926. (Okeh and Columbia were two other prominent labels.)

Paramount records started out as a New York subsidiary of the Wisconsin Chair Company (of Port Washington, WI). But as a recording company, it would eventually offer a very impressive roster of artists, including Blind Lemon Jefferson, Ida Cox, Lovie Austin, and others. Unfortunately for posterity, Paramount, unlike Columbia (for which Bessie Smith recorded), used a comparatively crude version of the acoustic method of recording, the results of which did not guarantee a great sound. Paramount was said to have changed to an electric method of recording in the mid-1920s. However, the standing joke of the time amongst recording artists was that Paramount’s new electrical method of recording meant simply that someone had switched on an electric light in the recording studio.21

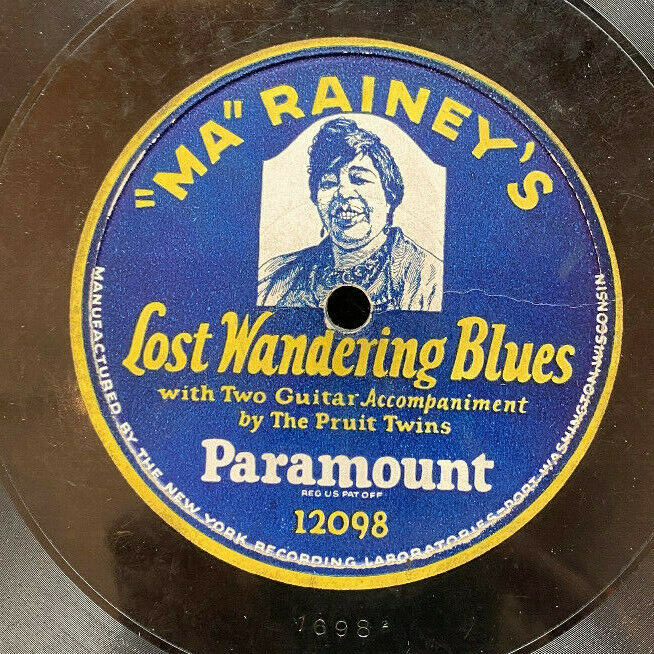

Nonetheless, Rainey would eventually make 94 recordings for Paramount, which is a significant body of work.22 Furthermore, Paramount advertised her work extensively in the black-owned press, particularly the Chicago Defender. For instance, Paramount offered a significant number of prizes to the public for naming a record released as Ma Rainey’s Mystery Record. They also released a “souvenir record” with a label which had Ma Rainey’s countenance emblazoned upon it (this was a recording accompanied by the Pruitt Twins on guitars), and Paramount proudly proclaimed that it was the first recording with a picture of the artist on the label.23 Paramount continued its adulation of Rainey unabated, until around 1927, when they suddenly relegated her image to a smaller portion of an advertisement in the Chicago Defender. This may have been a sign of shifting public musical tastes, but as much as anything, major cracks were beginning to appear in the economy. After 1928, the Defender only had one more advertisement for Ma Rainey’s work, and she stopped recording shortly thereafter. Business was becoming worse for all black performers, and this also affected the respective recording companies.24

Mention in Local Press

Before the 1920s economy started to take a downturn, we can find a number of references to Rainey in local African American press. For instance, there is a notification of her performing with her “Orchestra and Jazz Hounds” at midnight on the Savoy Roof Garden, Mechanics Bank Building, “Monday night on the stroke of twelve,” late in 1927 in Richmond, Virginia. It also mentions a concert to be performed the following week at the “True Reformers Hall.”25

A midwestern newspaper, The Ely Miner, in Minnesota,26 advertises Rainey’s record, Memphis Bound Blues and Rough and Tumble Blues, for seventy-five cents postage paid, and gives a post box address for Paramount’s distributors in Memphis, Tennessee.27

The Minnesota African American newspaper, The Northwestern Bulletin-Appeal,28 gives an account of how Ma Rainey had inadvertently bought $25,000 worth of stolen jewels in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and was forced to return them to the authorities around November 5, 1924. The fact that she had that considerable sum to spend on jewelry indicates that at this time, Ma Rainey, was clearly a wealthy woman.29

And most surprisingly, I discovered an advertisement for Ma Rainey’s Mystery Record (along with records by jazz cornetist Johnny Dunn and blues singer Ida Cox) in the Omaha Nebraska Monitor in 1924. The Great Migration north from the American South by many African Americans30 resulted in the black population of Omaha doubling from approximately 5,000 to 10,000 from 1910 to 1920. So, while Rainey may not have performed in any tent shows that far North, there certainly was a large enough black population in Omaha to buy and enjoy her records. And records were, generally speaking, not inexpensive in the 1920s. Most people anywhere could not afford to buy them, so some people in the black community in Omaha at that time must have had a disposable income.31

Final Years

Rainey’s final years were comparatively quiet, away from the limelight (both literally and metaphorically). Bessie Smith died tragically in an automobile accident in 1937, and Ma Rainey died only two years later. Although Rainey’s death certificate sadly lists her occupation as “Housekeeping,”32 she was known to have managed three local theaters in Georgia at the time of her death, namely, The Liberty in Columbus, and the Lyric and Airdrome in Rome.33

The Records of Ma Rainey

Much of what we do know for certain about Ma Rainey is rather paltry, a sad indication of the low esteem in which many popular artists from early 20th century America are held by both the country at large, and by academe as well. But we do have her recordings. And they tell us a great deal.

For instance, there are a number of her records which give an example of the “theatrical” or vaudeville roots of Rainey’s performances, for instance, Gone Daddy Blues.34 In this particular song, we can hear Ma Rainey giving a vaudeville type of performance (I strongly suspect that this was just her stage persona, and had little to do with reality) about a faithless wife trying to get back together with her husband after becoming dissatisfied with her lover. It even starts with a knocking noise (presumably a knock on the door), which moves into a short dialogue between Rainey and an unidentified man, then promptly moving into a song, much as one might find in vaudeville routines and musical comedies.35

Another example (and there are many), is her recording of Ma and Pa Poorhouse Blues.36 At the beginning of this record, we hear another “comic turn,” which most likely came from a vaudeville routine. In this one, we hear a character referred to as “Charlie,” and Rainey talk about their impoverishment. Charlie describes how he’s had to pawn his banjo,37 and Ma discusses how her touring bus was stolen. It’s most likely that none of this was true (Rainey still had her touring bus in 1928 when this recording was approximately made), but it treats poverty with an irreverent tone, and would have endeared her audience to her every bit as much as her singing.

Stylistically, perhaps because her singing is overwhelmingly “earthy” and “rural” in nature, she quite often does not “land” on the notes exactly. What she does is either “slide down” to them, or “slide through” them with a glissando (a glissando is where the singer passes through several notes so quickly that the ear can’t detect exact pitches). Listen to the first 17 seconds of Lawdy Send Me A Man Blues.38 You’ll hear that the pitches (notes) are not 100% determined a lot of the time. Towards the 45 second mark, you’ll hear her use a couple of “grace notes” – these are very quick “ornaments” which emphasize the longer note used. This actually shows a lot of subtlety.

Then, a second or two later when she sings, “Oh, Lawd, Send Me a Man,” on the word, “Lawd” we can hear what’s called an “indeterminate pitch.” This is where she glissandos through the notes and doesn’t stop, and fades out quickly with her voice. I defy you to sing along at this point. This actually requires a fair degree of skill in order to make it sound beautiful and musical. And when she sings the word, “Man” you’ll hear her slide up from the sharpened second note in the scale, to the third note in the scale (this is sometimes called a “blue note”). This shows the use of what we call “microtones” (that is, notes which are smaller than the accepted smallest distance between two notes in western music, i.e., a semi-tone).39 This is something we find not just in Bix Beiderbecke’s cornet playing, but also in contemporary experimental western “art” music of the early 20th century.

Ma Rainey’s records are also important because of the accompanying instrumentalists. In one of her most famous recordings, Lost Wandering Blues,40 she is accompanied by the Pruitt Twins who are playing banjo and guitar.41 Listen to the approximate 1 minute and 5 second mark – you will hear the accompanists just playing the second and fourth beats (i.e., instead of ONE-TWO-THREE-FOUR, we hear them play, silence-TWO-silence-FOUR), with Rainey’s voice soaring over the top of them. And before that, at around the 15 and 25 second mark, you will hear the instrumentalists playing much more quickly, then slowing down immediately after the quickly played phrase. This is known as “double-timing,” and adds great interest to any jazz performance. Jelly Roll Morton was a Master of this technique.

Ma Rainey’s records are also important because of the accompanying instrumentalists. In one of her most famous recordings, Lost Wandering Blues,40 she is accompanied by the Pruitt Twins who are playing banjo and guitar.41 Listen to the approximate 1 minute and 5 second mark – you will hear the accompanists just playing the second and fourth beats (i.e., instead of ONE-TWO-THREE-FOUR, we hear them play, silence-TWO-silence-FOUR), with Rainey’s voice soaring over the top of them. And before that, at around the 15 and 25 second mark, you will hear the instrumentalists playing much more quickly, then slowing down immediately after the quickly played phrase. This is known as “double-timing,” and adds great interest to any jazz performance. Jelly Roll Morton was a Master of this technique.

And although Ma Rainey’s repertoire were largely 12 bar and 8 bar blues, she was able to show her range by recording approximately 20 sides which were popular songs rather than genuine blues. In this genre, particularly fascinating is Trust No Man,42 where she is accompanied in fine form by Lillian Henderson on the piano. At around the 1 minute and 55 second mark, we can hear her talk (or rather “shout”!) the lyrics instead of singing them straight. This displays a lot of diversity in the use of both style and timbre of voice.

But Ma Rainey showed great subtlety and good taste in her choice of both musicians and combinations, as well. In See See Rider Blues,43 we get to hear Rainey accompanied by jazz greats Louis Armstrong on cornet (not trumpet), Buster Bailey on clarinet, Charlie Green on the trombone, Fletcher Henderson on piano, and (most likely) Charlie Dixon on the banjo. All the accompanists play in an understated fashion, very contrapuntally and individually, but at the same time are completely at the service of Ma Rainey’s singing, and do not overpower her. It is one of Ma Rainey’s greatest recordings, and I suspect that it is at least partially due to Fletcher Henderson’s good taste and sensitivity, that this is one of the great blues records of all time.

Conclusion

So why are Ma Rainey’s records so musically important? Let’s provide the answers in point form:

- They give us our earliest examples of what vaudeville singing of African American theatre sounded like before the 1920s;

- They give us clear examples of how the dialogue from the comic turns and vaudeville routines merged into the singing;

- They show us how Ma Rainey deviated from the written note in her numbers which are “popular songs” (as opposed to blues songs) and how she was apparently one of the first singers to do so;

- They show us how she may have been one of the first singers to glide or glissando through notes, sing indeterminate notes, and sing micro-tones;

- They show us the great breadth of taste and variety in methods of accompaniment which were available to her;

- They show a masterful melding of instrumental ensemble work with her very distinctive singing style; and finally,

- They give us one of the best examples of how blues developed from a more rural style to a more cosmopolitan expression exemplified by singers like Mamie Smith and Bessie Smith – i.e., by showing elements of early southern vaudeville, the tent show music of the 1910s, melded with the more sophisticated jazz accompaniments of the 1920s.

I suspect the reason why Ma Rainy is not better appreciated today is not just because of the more rural style. Unfortunately, it is also perhaps due to the poorer engineering of the records made by Paramount at the time she was recording for them. In addition, she has not fared so well with reissues. One of the earliest reissues was on the Milestone Jazz Classic label around 1974. I am not too enamoured of this series, because the producers tended to lop off all the high frequencies, and most of the 78 rpm records reissued by them tend to have a “muffled” sound, in my opinion.

Biograph Records released a few LP vinyl records of her work, the best of which I thought was in 1971, Queen of the Blues.44 While I think that these were good reissues, many people might be put off by the surface noise because Biograph rarely did any filtering to remove the “scratchiness” of early 78 rpm records. Lawd, Send Me a Man Blues does not have a lot of surface noise on this album, however.

The Complete Gertrude Ma Rainey Collection 1923/28 Vol. 1 (on the King Jazz [KJ] label), also presents her work well, but like the Biograph albums, they don’t use much if any filtering to remove scratch. So, while I love these selections, there are some who might not. The same could be said for the Document Records releases which included all her records over several compact discs.

Finally, the Acrobat label released a four-disc, 94-track set featuring all of Ma Rainey’s work in 2019 with some of the newest technology (The Definitive Collection, 1924 – 28), where the surface noise is “managed” rather than “removed.” What I am unclear about, however, is why this company would spend all this time and money digitally re-processing all of Rainey’s work so nicely, but then ruin almost every track by cutting off the beginnings of the first notes at the beginning of each record and then end of the last notes at the end of each record. In my opinion, shoddy engineering ruined what was otherwise a really excellent release. So sadly, there is no perfect solution for listening to her great musicianship.

Rainey has also not been well-served by biographical writers, either. There is really only one serious book about her (by Sandra Lieb), but it was written more than forty years ago; only one chapter dealt with her biographical details; there were no musical analyses given; and one wishes that the author had spent more time researching various newspapers, interviewed more people who knew Rainey when they were still alive, and that the author had had access to modern digital and web-based research techniques.

While this situation is absolutely unconscionable, we do still have her recordings. Her 94 wonderful, soulful, and musically eloquent recordings, which have touched the lives of literally hundreds of thousands of people over the course of almost 100 years. Hopefully they will be better preserved and researched in the years to come. And if you have never heard her records before, you are in for a real treat.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my gratitude to Whit Gaines and Rashael Apuya of the Columbus (Georgia) Public Library, for having brought various articles to my attention. In particular, the interview with Rainey’s 84-year-old niece, Ella Mae Sanders which was found in the Columbus Ledger-Enquirer. Thanks also to Max Morath for one small, but vital, piece of information upon which my arguments hinged.

PHOTOS

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ma_Rainey, PD,

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ma_Rainey PD, Left to right: Ed Pollack, Albert Wynn, Thomas A. Dorsey, Ma Rainey, Dave Nelson, and Gabriel Washington in 1923

- Record Label for Lost Wandering Blues, PD, from discogs.com

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lieb, Sandra R., Mother of the Blues: A Study of Ma Rainey, The University of Massachusetts Press, 1981.

ENDNOTES

1 Schuler, Vic, and Lipscombe, Claude, Mystery of the Two Ma Raineys, in Melody Maker 25; 9, (October 13, 1951), [Lieb, pp. 1 – 2.]

2 Lieb, pp. 2 – 3.

3 Lieb, p. 4

6 Lieb, p. 5

7 Lieg, p. 8

8 Lieb, p. 7

9 Max Morath in telephone conversation with the author, July 30, 2022.

10 Lieb, p.10, the author provides details of her interview with one Clyde Bernhardt of one Rainey’s shows in Badin, North Carolina in 1917.

11 While the size of circus shows of the Ringling Brothers seems to have been larger than the advertisement in Note 12, there seems to be a similarity in the types of entertainment, including blackface comedians and musicians, https://classic.circushistory.org/History/Ringling1900.htm

12 Undated advertisement on the website of the Facebook page of the Ma Rainey house in Columbus, Georgia, https://www.facebook.com/MaRaineyHouse/photos/10154899313000616

13 Lieb, p. 12

14 Lieb, p. 17

15 Lieb, p. 17 – 20

16 Columbus Ledger-Enquirer, p. A1 & A12, April 27, 1992. An interview with Rainey’s 84-year-old niece, Ella Mae Sanders, reveals how Sanders walked out of the theatrical version of “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” because the portrayal of Rainey apparently had next to nothing to do with reality. Sanders is quoted in the article as saying, “Aunt Gert wasn’t like the way they made her seem. She was a genuinely nice person, and she wouldn’t tolerate vulgarity from the people who were around her. She and her husband, “Pa” (William) Rainey were very business-like.” She concluded that she may have been “flashy” in her choice of clothing, but she was not “foul-mouthed.”

17 Sterling Brown recalled this comparison and is quoted in Lieb, p. 17

21 Lieb, pp. 21 – 22

23 Lieb, p. 25

24 Lieb, pp. 39 – 45

25 Richmond Planet, Virginia, September 17, 1927, p. 4, for more information about this newspaper, please see, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84025841/

27 The Ely Minder, MN, December 18, 1925, p. 5.

29 The Northwestern Bulletin-Appeal, November 15, 1924, p. 4. The article also mentions that the alleged thief gave the “confession” only after experiencing the “third degree” from local police, so that is no indication that either the jewels were stolen, or the alleged thief stole them. This is because coerced confessions, by modern standards are not a confession, but an admission, and don’t stand up in court. What is interesting about this article, however, is that Ma Rainey was well enough known in the Midwest to warrant a relatively long article, and the article shows that she also performed in Pennsylvania as well.

31 Omaha Nebraska Monitor, June 27, 1924, p. 3, made available through the Library of Congress’ “Chronicling America,” website (https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/ ) More information about black migration to Omaha may be found at the following website: https://nebraskastudies.org… Apparently, although there was a small black community in Omaha from 1910 to 1920, most employment that black people were able to obtain there did not pay particularly well.

32 Lieb, pp. 47 – 48

35 Lieb, pp. 54 – 55 provides a transcription of the dialogue.

37 This is, I suspect, Charlie Dixon, who plays banjo on See See Rider Blues. That would make the most sense to me.

39 To learn more about microtones, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microtonal_music

41 Although the label states that there are only two guitars accompanying Rainey, when I listen to it, I hear a banjo and a guitar.

Matthew de Lacey Davidson is a pianist and composer currently resident in Nova Scotia, Canada. His first CD,Space Shuffle and Other Futuristic Rags(Stomp Off Records), contained the first commercial recordings of the rags of Robin Frost. Hisnew Rivermont 2-CDset,The Graceful Ghost:Contemporary Piano Rags 1960-2021,is available atrivermontrecords.com.A 3-CD set of Matthew’s compositions,Stolen Music: Acoustic and Electronic Works,isavailable through The Sousa Archives and Center for American Music University of Illinois (Champaign/Urbana),sousa@illinois.edu.