Williams was born on the outskirts of New Orleans, in Plaquemine, Louisiana, on October 8, 1898. He was of Choctaw Indian and Creole heritage. His father was a bass player who made his living as a hotel owner, and as a child, Williams began his musical education performing in the family hotel and singing in the streets. When he was twelve, he left home and joined Billy Kersands’s famous minstrel show as a singer. Shortly thereafter, he became the troupe’s master of ceremonies.

On Williams’s return to New Orleans, he started a suit- cleaning service for the many style-conscious piano professors in that city. He began playing piano in the honky-tonks of New Orleans’s Storyville. In this legendary red-light district, Williams, a man not noted for his modesty, admitted that he was overshadowed by Tony Jackson, the influential rag pianist who wrote Pretty Baby. Williams also played professionally with Sidney Bechet and Bunk Johnson, two future jazz stars.

He invested much of his time in learning new material, even writing to New York for the latest songs. During this period, he also managed his own cabaret, and wrote his first money-making composition, “Brownskin, Who You For?” recorded on Columbia Records. The $1,600 check he received for it in 1916 was, according to Williams, the most money anyone in New Orleans had ever made for a song.

Around 1915, he and Armand Piron started a New Orleans-based publishing company, which was in business for several years. Piron was a bandleader whose most famous composition was “I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate“. In 1917, he and Williams put together a vaudeville act, and they achieved moderate success with Piron on the violin and Williams playing piano and singing.

While touring, they became acquainted with W. C. Handy, who helped them place some of their compositions in Memphis music stores. When an important concert in Atlanta was moved from a black auditorium to a white one because so many whites wanted to attend, Handy asked Williams and Piron to join him to strengthen the program. The concert was a triumph, and the New Orleans duo stopped the show.

About this time, Williams claimed to be the first songwriter to use the word jazz on a piece of sheet music, and his business card began touting him as “The Originator of Jazz and Boogie Woogie.” Williams’s writing partner on some songs during the late teens was Spencer Williams (no relation). Their “Royal Garden Blues” became a jazz classic in the Dixieland style.

Anticipating the exodus of talent from New Orleans to the northern cities spurred on by the closing of Storyville, Williams moved to Chicago in 1920. The music store he opened near the Vendome Theater (the first store was located at 4404 South State Street) proved so lucrative that he eventually owned three music stores in the city, but Williams did not confine his energies to mere proprietorship. 1920 was the year Mamie Smith recorded Perry Bradford’s “Crazy Blues” and “It’s Right Here For You“. When the public got their first hearing of a black woman’s voice singing the blues, they wanted more, and Williams’s entrepreneurial skills enabled him to profit from this next phase in the entertainment business: selling recordings of black female blues singers.

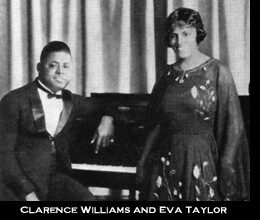

In 1921, Williams married blues singer Eva Taylor. She was one of the first female Blues singers heard on the radio, and her performances and style influenced many future vocal stars. Among the songs she and her husband collaborated on and performed together was “May We Meet Again,” written “in memory of our beloved Florence Mills,” one of the most popular black stage entertainers of the time.

In 1921, Williams married blues singer Eva Taylor. She was one of the first female Blues singers heard on the radio, and her performances and style influenced many future vocal stars. Among the songs she and her husband collaborated on and performed together was “May We Meet Again,” written “in memory of our beloved Florence Mills,” one of the most popular black stage entertainers of the time.

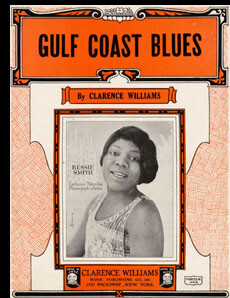

Williams understood the potential selling-power of New Orleans music in the North, and since New York City was the center of the music publishing business, he sold his Chicago music stores in 1923 and moved there. He rented space in the Gaiety Theater Building at 1547 Broadway, which was already established as an office building for other African-American entertainers including Bert Williams, Will Vodery, Pace and Handy, and Perry Bradford, and in February of that year, he and Bessie Smith went to Columbia to record her first sides.

The first two releases featured Smith accompanied by Williams on piano; one, “Gulf Coast Blues“, was even composed by Williams and published by his company. Williams accompanied Smith on many of the songs she recorded during that highly productive year and claimed writer’s credit on such numbers as “Baby, Won’t You Please Come Home” and “T’ain’t Nobody’s Bizness If I Do“. It should be noted, however, that Williams had a reputation for claiming credit for works he did not compose entirely on his own, and the origins of many of these songs remain in question.

The first two releases featured Smith accompanied by Williams on piano; one, “Gulf Coast Blues“, was even composed by Williams and published by his company. Williams accompanied Smith on many of the songs she recorded during that highly productive year and claimed writer’s credit on such numbers as “Baby, Won’t You Please Come Home” and “T’ain’t Nobody’s Bizness If I Do“. It should be noted, however, that Williams had a reputation for claiming credit for works he did not compose entirely on his own, and the origins of many of these songs remain in question.

He was also less than honest with the singer. He convinced Smith that she was under contract to Columbia. In reality, she had signed a contract naming him as her manager, and he was pocketing half of her recording fee. This episode came to a swift conclusion when Smith and a boyfriend made a surprise trip to Williams’s office, demanding that she be released from that obligation and allowed to sign directly with Columbia.

Not all of his activities were so self-serving. Willie “The Lion” Smith, who claimed that Williams was the first New Orleans musician to influence jazz in New York, also credited Williams with helping other African-American songwriters like himself, James P. Johnson and Fats Waller. From 1923 to 1928, Williams was the artist and repertoire director for Okeh Records, and from this powerful position he was able to seek out and develop new talent. During this time, he organized numerous sessions which advanced the careers of many early jazz greats such as Louis Armstrong and Sidney Bechet. He also employed a number of other jazz musicians including Don Redman, King Oliver and Coleman Hawkins.

A shrewd businessman, Williams was in a position to help new artists in many ways. He could arrange their recording sessions, supply their material, publish their compositions and manage their business affairs. He was also capable of taking advantage of the unknowing performer and did so, probably with the same regularity as white agents, who were not known for their even-handed dealings with artists regardless of their race.

Between 1923 and 1937, Williams proved to be a prolific producer, organizing at least two recording sessions a month and recording over 300 sides under his own name. It was common for him to record with one company and, if he didn’t like the results, go across town and record the same session for another company under a different name. The Dixie Washboard Band and Blue Grass Foot Warmers are but two of the pseudonyms he used in his pursuit for the best possible session.

In 1927, Williams tried his hand at musical theater. He wrote the book and music for and also produced the show “Bottomland,” which starred his wife, Eva Taylor. The show was not a critical success. However, Williams’s New York publishing company prospered, continuing to do business until 1943 when he sold its catalog of over 2,000 songs to Decca for a reputed $50,000.

From the late thirties until he lost his sight after being hit by a cab in 1956, Williams spent most of his time composing. He died in Queens, New York on November 6, 1965. During his lifetime, he had been a composer, pianist, vocalist, record producer, music publisher and agent. He may not have been the inventor of jazz, but he was influential enough in his day to be forgiven that one exaggeration.

by Thomas L. Morgan from his book From Cakewalks to Concert Halls : An Illustrated History of African-American Popular Music, From 1895-193“, by Thomas L Morgan & William Barlow. If you would like to order a copy of this book click here for details. (Used with permission of the author)

Copyright 1992 by Thomas L. Morgan https://tlmorgan.com/

| Title | Recording Date | Recording Location | Company |

| A Pane Of Glass (Clarence Williams) |

2-12-1929 | New York, New York | Victor V-38524 |

| Farmhand Papa (Clarence Williams) |

7-20-1928 | New York, New York | Columbia 14341-D |

| Gravier Street Blues (Clarence Williams) |

7-28-1924 | New York, New York | Okeh 40172-A |

| How Could I Be Blue (with James P. Johnson) (Dan Wilson / Andy Razaf) |

1-31-1930 | New York, New York | Columbia 14502-D |

| If You Don’t Believe I Love You, Look What A Fool I’ve Been (Clarence Williams) |

10-11-1921 | New York, New York | Okeh 8020-B |

| I’ve Found A New Baby (with James P. Johnson) (Jack Palmer / Spencer Williams) |

1-31-1930 | New York, New York | Columbia 14502-D |

| Michigan Water Blues (Clarence Williams) |

6-18-1930 | New York, New York | Okeh 8806 |

| Mixing The Blues (Clarence Williams) |

5-1923 | New York, New York | Okeh 4893-A |

| My Own Blues (Clarence Williams) |

7-28-1924 | New York, New York | Okeh 40172-B |

| My Woman Done Me Wrong (As Far As I’m Concerned) (Clarence Williams) |

7-20-1928 | New York, New York | Columbia 14341-D |

| Organ Grinder Blues (Clarence Williams) |

7-2-1928 | New York, New York | Okeh 8604 |

| Shooting The Pistol (Clarence Williams) |

8-19-1927 | New York, New York | Columbia 14241-D |

| Too Low | 2-12-1929 | New York, New York | Victor V-38524 |

| Wallflower Rag (Clarence Williams) |

7-2-1928 | New York, New York | Okeh 8604 |

| The Weary Blues (Artie Matthews) |

5-1923 | New York, New York | Okeh 4893-B |

| When I March In April With May (Clarence Williams) |

8-19-1927 | New York, New York | Okeh 14241 |

| You Rascal You (Sam Thread) |

6-18-1930 | New York, New York | Okeh 8806 |

| Title | Recording Date | Recording Location | Company |

| Kansas City Man Blues (Clarence Williams / Johnson) |

4-1924 | New York, New York | QRS 2586 |

| My Pillow And Me (Clarence Williams / Tim Byrmn / Chris Smith) |

5-1923 | New York, New York | QRS 2248 |

| Papa-De-Da-Da (Clarence Williams) |

1-1926 | New York, New York | QRS 3302 |

| Sugar Blues (Clarence Williams / Lucy Fletcher) |

4-1923 | New York, New York | QRS 2172 |

| Them Has Been Blues (Clarence Williams) |

11-1926 | New York, New York | QRS 3716 |

| What’s The Matter Now? (Clarence Williams) |

7-1926 | New York, New York | QRS 3529 |

| Clarence Williams by Tom Lord, Storyville Publicatons, Ltd., 1979 |

Redhotjazz.com was a pioneering website during the "Information wants to be Free" era of the 1990s. In that spirit we are recovering the lost data from the now defunct site and sharing it with you.

Most of the music in the archive is in the form of MP3s hosted on Archive.org or the French servers of Jazz-on-line.com where this music is all in the public domain.

Files unavailable from those sources we host ourselves. They were made from original 78 RPM records in the hands of private collectors in the 1990s who contributed to the original redhotjazz.com. They were hosted as .ra files originally and we have converted them into the more modern MP3 format. They are of inferior quality to what is available commercially and are intended for reference purposes only. In some cases a Real Audio (.ra) file from Archive.org will download. Don't be scared! Those files will play in many music programs, but not Windows Media Player.