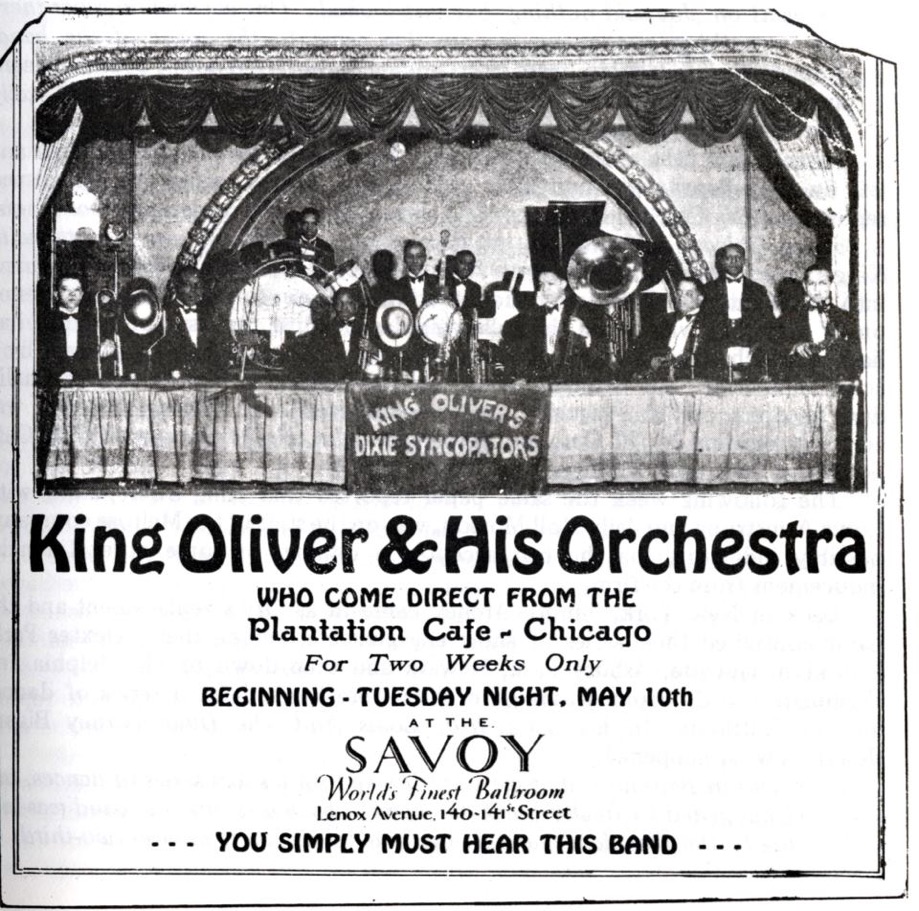

Jeff Barnhart: Hal, after our in-depth exploration of a single tune, it’s time to broaden our scope to the music of the immortal Joe “King” Oliver. The twist this month is that we’ll take up his career post-Creole Jazz Band, beginning in 1926. In 1924, Louis Armstrong had left that band, and Chicago, at the urging of pianist (and by now wife) Lillian Hardin (Armstrong) to follow his fortunes East to New York. Joe Oliver never again found the chemistry created by his initial band, the first black band to record jazz. His output in 1924-25 only consisted of inclusion as a blues accompanist to Butterbeans and Susie, and then Sippie Wallace, as well as two remarkable duo sides with Jelly Roll Morton. Increasing health problems would add to his fading star, but in 1926 he was still going strong and put out an impressive number of sides with his 10-piece band, first called King Oliver’s Jazz Band and then King Oliver’s Dixie Syncopators (among other names depending on what label released the side). They were playing real hot jazz! Hal, please share any insights you have into the creation of Oliver’s band(s) from 1926 and take us into our first number!!

Hal Smith: Jeff, I am a real fan of the Oliver recordings from 1926 and 1927 for several reasons: the electrical recordings allow us to hear the band much better than on the 1923 acoustic sides; there are several examples of just how great Oliver could play before he completely lost his “chops”; the band personnel included some of my favorite New Orleans musicians—especially trombonist Kid Ory; the songs chosen for recording were, for the most part, well-suited to the orchestra and the arrangements gave almost everyone a chance to show their stuff.

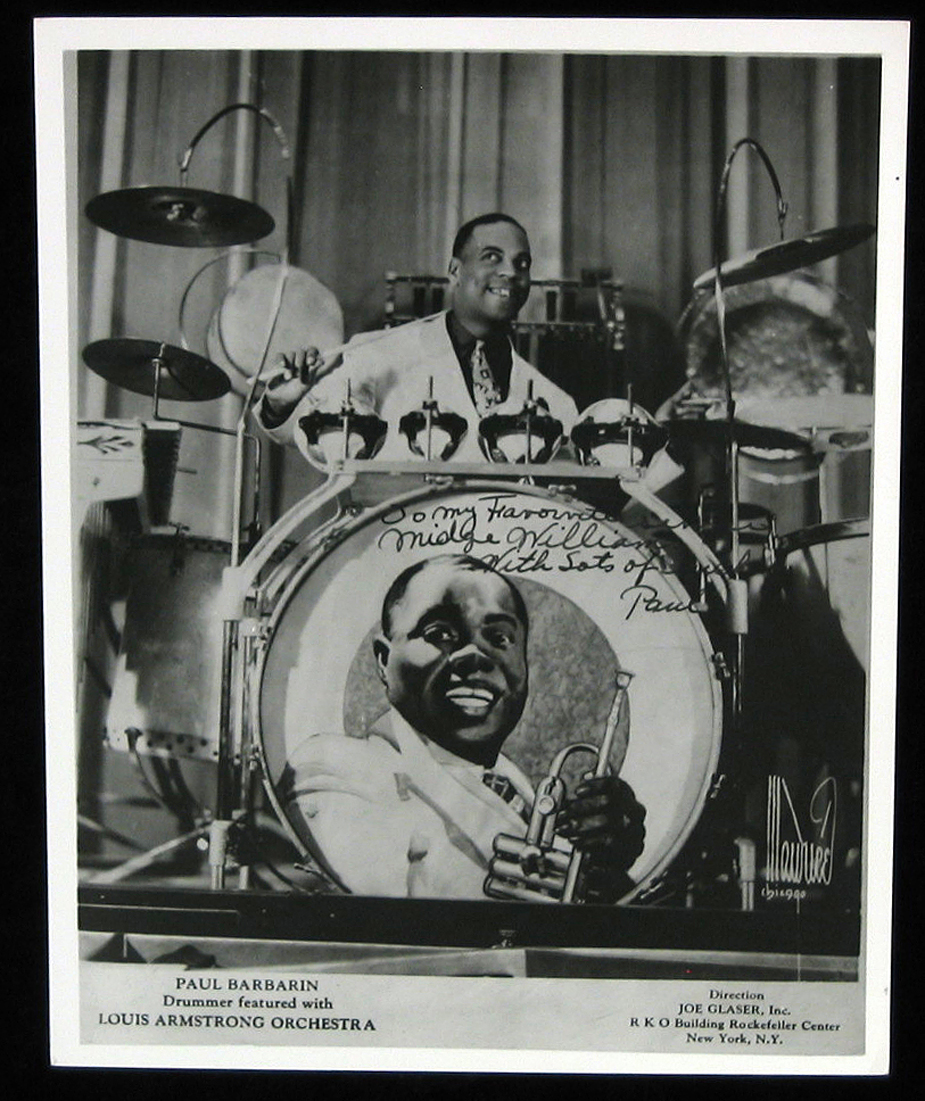

The first recording in the series is Elmer Schoebel’s “Too Bad” and it comes on like gangbusters! The ensemble is roaring away, right from the first note, with propulsive bass drum and cymbal accents from drummer Paul Barbarin. There is a key change from Eb to Ab. Listen as banjoist Bud Scott shifts his rhythm from straight 4/4 to accenting 2 and 4. Barney Bigard plays a slap-tongue tenor sax solo, and the ensemble repeats the first strain. Next, it’s back to Ab with solos by Ory and a clarinet trio, followed by Bud Scott’s vocal break. On the repeats of the Ab strain, Ory plays two breaks with upward glissandos, then comes the highlight of the side: two muted, ascending breaks by King Oliver. “Too Bad” certainly is an auspicious start to the series of 1926-1927 recordings by King Oliver. What do you hear on this one, Jeff?

JB: For fun I went searching for other versions from 1926. I couldn’t find that the Schoebel outfit recorded his own tune, but I found one from Abe Lyman’s Orchestra. While that cut is hot for a dance band, it withers in the shadow of Oliver’s band’s rendition. Perhaps one reason was the killer band around him; some of whom would head to New York (Paul Barbarin, Albert Nicholas) with pianist Luis Russell. I love all the highlights you included, I enjoy hearing Bud Scott cutting the rhythms in the A strain and how Ory bends, then flattens the fifth note of the melody in Ab from a C to eventually a full-fledged Cb (a REAL blue note): NOT what Schoebel wrote, but each iteration is dirtier and dirtier. AWESOME! All the breaks on the final three out-choruses are exciting: Scott’s, then Ory’s, and then the King himself. When I first heard this track, that double ending demanded I listen five more times! WHAT a start!

On the opposite end of the tempo spectrum, “Snag It” is a gutbucket blues, the wail of the brass trading with sax and piano doubling the response for the intro; an ensemble blues chorus gives way to trombone playing melody over dense organ-tone chords from reeds and tuba, Bud Scott keeping the four-beats moving forward. Albert Nicholas solos on soprano sax over an intricate riff backing by ensemble (two things about this: the band excelled at devising inventive backgrounds throughout their recording span and unusually, every reedman played soprano sax in addition to clarinet, with two altos and Bigard on tenor).

Richard M. Jones staidly sings the words for a chorus and then…magic! Oliver plays one of the most famous and reproduced four-bar solos, over breaks, in jazz history and leads the band through the remainder of the hot blues ensemble, then clarinets and brass alternate phrases under Jones’ invasive and unnecessary vocal commentary. The second chorus repeats the first, but with clarinets playing their figure up an octave to increase the excitement! Hal, what have I missed?

HS: I think “Snag It” is one of the best of the best in this series of recordings. Ory’s muted solo is simple, but just beautiful. I love that complex rhythm behind the soprano solo (and I play it fairly often on the choke cymbal behind soloists on slow blues)! One thing you didn’t mention, but I’m sure you noticed: the ensemble dynamics as they alternate between a near-whisper and a shout behind Richard M. Jones’ vocal.

Speaking of Richard M. Jones: he is the pianist on this side. I wish we could have heard more of him, as he was an excellent jazzman! King Oliver’s cornet breaks are majestic and they have been quoted many times over the years on other recordings of the song. On the 10th and 11th bars of the break chorus, Oliver plays a blues phrase which shows up in quite a few of Bunk Johnson’s recordings from the 1940s. Oliver and Bunk were acquainted and I have read that Oliver asked Bunk to “send some more blues” for The King to play with his own groups. Who knows?

JB: Hal, not only were the King and Bunk acquainted, but Armstrong biographer Thomas Brothers avers Oliver sent for Bunk (then Kid Rena) to come north to Chicago before he sent for Louis. Bunk’s and Rena’s both saying “no thanks” was part of the reason Louis got the gig!

Regarding “Snag It,” for some reason, they thought a second take on March 11 was necessary! Take 2 is at a faster clip, made even more so by Bud Scott’s rushing the beat in the intro—there’s a 21-second difference in the length between takes—and the only improvement to me is Jones’ vocal is looser. I’m not sure why they bothered, although it’s great to hear Oliver nail his solo breaks at this tempo! Also, Jones’ vocal interpolations are different; he doesn’t say “mess around” on the final chorus and on the penultimate one, he cries out, “Snag it, Papa, Snag it!” (In addition to his soubriquet “King,” Joe Oliver was known as “Papa Joe” to Armstrong and others). I still prefer the first take!

HS: I prefer the first take as well, but Oliver plays a beautiful solo after the cornet breaks on the second take. The vocal was left out of subsequent recordings by other bands, but I remember hearing “Papa Ray” Ronnei sing it with the South Frisco Jazz Band. (He played a wonderful Freddie Keppard-like variation on the cornet breaks, too).

Next up is “Deep Henderson”—a wonderful side. We hear just a bit of The King on the introduction, then Barney Bigard’s slap-tongued tenor sax on the first strain (with wonderful rhythmic backing by Bud Scott on banjo and Bert Cobb on brass bass) plus a nice sample of Luis Russell’s raggy piano. Albert Nicholas is the clarinet soloist on the second strain and there’s some beautiful Oliver cornet riding over the ensemble. After a key change, the third strain features the reeds stating the melody, with Oliver going to town over the ensemble and Ory joining in towards the end. Oliver takes the last break and even though it sounds like one of his valves may have stuck—I’ll take it!

JB: The tempo on this one is simply perfect, albeit Russell rushing during his unaccompanied piano interlude; I can see the dance floor filled with bouncing couples! Harmonically, this tune is quite snaky, making for exhilarating listening. Each of the three sections is beautifully composed and executed. Along with the highlights you pointed out on the C strain, I’ll add Cobb’s strutting tuba cutting figures underneath the melody from the clarinet trio. Facile, light and dancing. Worth pointing out as well how quickly these reeds players had to switch instruments; Kid Ory’s two bar break out of the first C chorus is all they have to put down their claris and pick up their saxes! Keep driving the music bus here, Hal: what’s next?

HS: “Jackass Blues” starts off with trombonist Kid Ory’s imitation of a mule braying. The first chorus is a loose ensemble, followed by a magnificent Oliver solo, another ensemble and a muted solo by Ory. Luis Russell almost sounds like Jelly Roll Morton on the modulation to F for Georgia Taylor’s vocal. After the lone vocal chorus, the orchestra immediately returns to the original key of Bb. Albert Nicholas solos on clarinet before one final ensemble, with Paul Barbarin’s ringing cymbal as the final punctuation mark.

JB: Ory’s intro hearkens back to the ODJB’s “Livery Stable Blues” with the animal imitation, but never descends into hokum. The King wails with clarion intensity, his crack at the end adding to the emotion. Russell’s piano underpinnings behind Ory’s solo is masterful as is his full, but not overbearing, backing to Taylor’s vocal. Nicholas takes his cue from Oliver and Ory, bursting into his solo—“signifying” was a term used back then: with all the treasures preceding it, I find the closing ensemble to be anticlimactic.

Our next 1926 tune has quite a history; originating in 1923 as “Dippermouth Blues” during the Creole Jazz Band days, it resurfaced in New York in 1925–Armstrong carried that tune with him to New York when he joined Fletcher Henderson’s band and asked Don Redman to arrange it for the group. The result was “Sugar Foot Stomp,” which listed Oliver and Armstrong as the composers. Armstrong plays his solo with an homage to Oliver but with more relaxed phrasing and a high 6th held through most of the third chorus.

In May 1926, Oliver and his band (called The Savannah Syncopators on Brunswick 3361–with Oliver listed as sole composer) assayed this reworking of “Dippermouth” at a brisker tempo than Henderson’s and with a wonderful use of dynamic contrast (the famous stop-time clarinet solo played first at blaring volume followed by a whispering statement in the chalumeau register). Ory gutbuckets his way through two choruses. Underneath Oliver’s classic solo the band replicates the riff rhythm heard on “Snag it” at a MUCH quicker tempo and after Bud Scott shouts “Oh play that thing,” the magic really begins: three out choruses build in texture starting with an arpeggiated downward riff for saxes, taken up by the trumpets in the second chorus with saxes noodling sotta voce and Ory tailgating with abandon; the third chorus continues this pattern with more intensity, and a double ending culminates in a held ensemble note topped off by Barbarin’s almost savage cymbal crash. So visceral compared to the (expecting Armstrong’s solo) fairly straight Henderson version.

HS: The ensembles are truly “every tub”—every man for himself. And as you mentioned, this tempo is very sprightly. I like the dynamics on the clarinet chorus (and the Jimmie Noone-like downward chromatic run the second time through). Ory’s muted solo knocks me out every time I hear it and those cymbal punctuations by Paul Barbarin are perfect! The “Snag It” rhythm sounds a little awkward behind the cornet, but it doesn’t seem to phase The King at all! Three glorious cornet solo choruses, then three arranged ensembles out. It’s kind of strange to hear the loose chorus first and an arranged chorus last, but there is so much great playing on this one that it still works.

JB: That might have been Oliver “thumbing his nose” at his Eastern brethren: “See, not only can we start with hot, loose, polyphonic jazz, but we can outdo your arranging at the end…take THAT!” LOL!

HS: The next track is my favorite—hands-down—of all the 1926-1927 King Oliver recordings. “Wa Wa Wa” is unbelievably good. This is one of the first records I’d grab if my house caught on fire. The introduction, with Oliver’s wa-wa mute and Ory’s shouted response, leads into a chorus with the reed section playing the melody, underpinned by the pulsating rhythm of Bud Scott’s banjo, Bert Cobb’s brass bass and Paul Barbarin’s authoritative cymbals.

The full ensemble plays the verse, setting up one of the greatest choruses in Classic Jazz: a full solo by Oliver—demonstrating that he still had what it took to be crowned “King.” A chorus by the clarinet trio, a rugged trombone solo by Ory (quoting one of Oliver’s phrases on the break), Albert Nicholas soloing over a loose ensemble, a blazing-hot break by Oliver and Bigard and then—WOW. That band must have been three feet off the ground on the last chorus. Even with three reeds it has a real polyphonic New Orleans sound: first and second cornets playing exactly the right parts, with Ory’s tailgate phrasing underneath. If you ever needed a definition of “stomp,” it’s the sound of this rhythm section on the last chorus. There is so much drive from Scott, Cobb and Russell that Barbarin is free to dance along on a woodblock rather than laying into the afterbeats on choke cymbal.

The full ensemble plays the verse, setting up one of the greatest choruses in Classic Jazz: a full solo by Oliver—demonstrating that he still had what it took to be crowned “King.” A chorus by the clarinet trio, a rugged trombone solo by Ory (quoting one of Oliver’s phrases on the break), Albert Nicholas soloing over a loose ensemble, a blazing-hot break by Oliver and Bigard and then—WOW. That band must have been three feet off the ground on the last chorus. Even with three reeds it has a real polyphonic New Orleans sound: first and second cornets playing exactly the right parts, with Ory’s tailgate phrasing underneath. If you ever needed a definition of “stomp,” it’s the sound of this rhythm section on the last chorus. There is so much drive from Scott, Cobb and Russell that Barbarin is free to dance along on a woodblock rather than laying into the afterbeats on choke cymbal.

Louis Armstrong once said, “No trumpet player ever had the fire Joe Oliver had. Man, he could really punch a number. Some might have had a better tone but I’ve never heard nothing have the fire, and no one created as much as Joe.” This side perfectly illustrates what Louis said.

JB: That final break by Oliver is ferocious! May 29, 1926, produced both “Sugar Foot Stomp” and “Wa Wa Wa,” and Oliver and every band member was flying!

We’ll skip the July 23, 1926 recording date (two rejects and an unremarkable release) and jump to Sept. 17, 1926, beginning with a relaxed version of the Spikes Bros’. “Someday, Sweetheart;” a four-bar intro with brass and reeds lobbing melodic phrases between them leads into Oliver’s plaintive statement of the verse with NO horn backing; a true solo moment and just lovely.

We’ll skip the July 23, 1926 recording date (two rejects and an unremarkable release) and jump to Sept. 17, 1926, beginning with a relaxed version of the Spikes Bros’. “Someday, Sweetheart;” a four-bar intro with brass and reeds lobbing melodic phrases between them leads into Oliver’s plaintive statement of the verse with NO horn backing; a true solo moment and just lovely.

Ory takes the final four bars and we’re treated to Bert Cobb’s lowing tuba playing the first half of the melody chorus into a looser sax interpretation of the bridge and final eight. Then, New Orleans clarinet star Johnny Dodds utilizes wide vibrato in the chalumeau register with yet more rhythmically inventive backing from the band; his chorus, sticking close to the melody, ends the tune—with a two bar tag. Oliver shows his generosity giving Dodds such a prominent role in this side.

HS: It’s interesting to hear Bert Cobb anticipating the beat on this one; sort of a “larrup” sound that reminds me of Simon Marrero’s brass bass playing on Papa Celestin’s early recordings. I don’t have anything to add to your description except to say how much I like that rhythm behind Dodds’ solo. Jelly Roll Morton used a similar background on the 1926 Red Hot Peppers record of the song. By the way, King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band recorded “Someday, Sweetheart” for Gennett in October, 1923. It was rejected by Gennett! Wouldn’t we like to hear that record?

The orchestra recorded “Dead Man Blues” on the same date, but let’s skip to the next side: “New Wang Wang Blues.” Kid Ory is fairly prominent on this one, from the introduction all the way to the end. He must have really taken to this song. His daughter Babette told me that it was one of his favorites to play with his own Creole Jazz Band!

JB: Great precision work from the reeds, a freakish, jittery interlude (the patter chorus in the piano/vocal version) and we’re off to the chorus stated by the reeds, after which the melody of the chorus is taken up by Ory as you pointed out. The patter chorus is repeated but with more solid rhythm and a final chorus with the outro echoing the intro. It’s a hypnotic tune; no wonder Ory included it in the repertoire of his later band!

Hal, it looks as if we’ve made our tune list bigger than our column space, so if it’s all right with you, let’s shelve 1927 (and 1928-30) for future columns; that will allow us to look in depth at the final side(s) from the date that produced the previous three titles listed above. Six months and a couple of days after recording their initial versions of “Snag It,” the band recorded it again, this time with, among other changes, Luis Russell playing piano instead of Richard M. Jones and a tuba solo in place of the vocal. Hal, what do you have to share regarding the versions they recorded on Sept. 17, in comparison to the release from March?

HS: As with the second take from March, the tempos on the September versions are quite a bit brighter. It’s interesting to hear the blues melodies that were floating around Chicago in the 1920s quoted on the soprano sax and brass bass solos.

JB: The second take is also more in control; they got the bug-a-boos out during the first try and now are settled in and “in the pocket.” Every solo is more relaxed. It’s interesting you point out blues “melodies” here as both Stump Evans and Bert Cobb play virtually the same solos on both takes; these were melodies indeed, not improvised solos over the blues changes.

HS: I’m actually glad that there are four takes of this song—if only for King Oliver’s solo choruses with the breaks and the lovely blues playing…AND the cornet tags! On the final version, we can hear Kid Ory really romping away in the last ensemble, too.

JB: Indeed! Excepting Oliver seeming nervous about executing his breaks (the second take is more authoritative) both takes are drenched in real deep blues. I also enjoyed that Barbarin added one choke cymbal hit to the figure he plays on the out-choruses in September, enhancing the syncopation!

HS: By the way, we should mention that all the King Oliver sides in this discussion are available on a compact disc released by a British company: FROG. The catalog number is DGF – 34 and it should be available from outlets such as the Louisiana Music Factory, Upbeat Records, Amazon and eBay. We also need to thank our good friend David Sager (trombonist, bandleader and jazz historian par excellence) for his assistance in getting all four takes of “Snag It” to us, with valuable commentary.

JB: For sure! He’s an invaluable source and is so generous with his time and insights. There are dozens more sides to enjoy from Oliver but lets head back to New Orleans and explore our favorite recordings by the terrific hot dance band, the Halfway House Orchestra.

HS: That’s jam-up with me. The HHO and the New Orleans Owls are two wonderful bands that should be much better known!

Jeff Barnhart is an internationally renowned pianist, vocalist, arranger, bandleader, recording artist, ASCAP composer, educator and entertainer. Visit him online atwww.jeffbarnhart.com. Email: Mysticrag@aol.com

Hal Smith is an Arkansas-based drummer and writer. He leads the El Dorado Jazz Band and the

Mortonia Seven and works with a variety of jazz and swing bands. Visit him online at

halsmithmusic.com