In the first quarter of the 20th century (1900–1925), the great migration of the African-American people took shape. They left their rural, country, backwoods habitats of the southern states of the U. S. and relocated in the northern cities of an emerging industrialized America. They brought with them their taste for music which was a staple of their spiritual and earthy lifestyle.

In the first quarter of the 20th century (1900–1925), the great migration of the African-American people took shape. They left their rural, country, backwoods habitats of the southern states of the U. S. and relocated in the northern cities of an emerging industrialized America. They brought with them their taste for music which was a staple of their spiritual and earthy lifestyle.

This musical impact combined with the technical growth of capitalist America to produce an urban industry; the entertainment industry. Names like Scott Joplin (Ragtime), W. C. Handy (Blues), Eubie Blake (Popular) and Louis Armstrong (Jazz) produced a lucrative and thriving music entertainment industry that exists and is viable up until this present time. The technology of this industry was almost totally in the hands of white Americans. Recording, the making of records in its beginning years 1900–1920, was a discriminatory process. White producers took the musical ideas of Blacks, but were reluctant to allow Blacks to make records. By 1920 the only Black voice to be recorded by the major companies was Bert Williams on Columbia and Mamie Smith on OKeh Records. One man, Harry Herbert Pace, was aware of this fact. He decided to act.

“Companies would not entertain any thought of recording a colored musician or colored voice, I therefore decided to form my own company and make such recordings as I believed would sell.” (The Negro in New York, 1939)

Harry Herbert Pace was born on January 6th, 1884 in Covington, Georgia. His father, Charles Pace, was a blacksmith who died while Harry was an infant leaving him to be raised by his mother, Nancy Francis Pace. Light skinned and extremely bright, Pace finished elementary school at age twelve and seven years later graduated valedictorian of his class in Atlanta University. A disciple of his college teacher, W. E. B. DuBois and his concept of the talented tenth, upon graduation, Pace worked in printing, banking and insurance industries first in Atlanta and later in Memphis. In various junior executive positions, he demonstrated a strong understanding of business tactics and had a reputation for rebuilding failing enterprises.

During his sojourn in the South, two significant things happened that would impact his figure. In 1912 in Memphis, he met and collaborated with W. C. Handy, generally recognized as the father of the Blues. Handy took a liking to Pace, they wrote songs together. Later they would develop the Pace and Handy Music Company, that would bring Harry Pace to New York City. Secondly, he met and married his wife, Ethlynde Bibb, who would be a great inspiration in his life. (African-American Business Leaders, Ingraham and Feldman.)

In 1920, Pace resigned his position in Atlanta, moved to New York, purchased a fine home on “Striver Row” in Harlem and settled in to manage the Pace and Handy Sheet Music business. The business using Pace’s business knowledge and Handy’s creative genius was very successful. While the company was profitable and artistically effective, Pace was frustrated. He observed as white recording companies bought the music and lyrics from Pace and Handy and then recorded them using white artists. When they did employ Blacks, they refused to let them sing and play in their own authentic style. Pace resolved to start his own record firm. Many scholars for years believed Handy was part of Pace company. Handy stated:

To add to my woes, my partner withdrew from the business. He disagreed with some of my business methods, but no harsh words were involved. He simply chose this time to sever connection with our firm in order that he might organized Pace Phonograph Company, issuing Black Swan Records and making a serious bid for the Negro market. … With Pace went a large number of our employees. … Still more confusion and anguish grew out of the fact that people did not generally know that I had no stake in the Black Swan Record Company.”

In the 1920’s New York, Harlem was ushering in a Negro renaissance of art and culture. Marcus Garvey (of whom Pace was a severe critic) was leading the largest Black mass movement for pride and economic redemption in twentieth century America. Even the Negro middle class, of which Pace was an undeniable member, was feeling the call to control the destiny of their lives, set up companies, manufacture products, employ and sell products to their own people. Pace was impacted by the wave of Black Nationalism sweeping the U. S. in the early 1920’s post World War I period.

Humble Beginnings

In March of 1921 under the laws of the state of Delaware and using about $30,000 in borrowed capital, Pace organized the Pace Phonograph Corporation, Inc. with a Board of Directors that included Dr. W. E. B. DuBois, Mr. John E. Nail, Dr. Matthew V. Bouttle and Ms. Viola Bibb. The company’s first office was his home at 257 West 138th Street New York, N. Y. The African-American newspaper, New York Age reported:

PHONOGRAPH COMPANY MAKING RAPID PROGRESS

Among the business organizations recently established by Negroes in New York, one of the most important is the Pace Phonograph Company. This company was incorporated in January 1921, under the laws of the state of Delaware on $110,000. The board of directors of the organization is composed of some of the most able colored businessmen.

Pace did not have an easy time entering the record business. White record companies threw up obstacles to keep him out. When he attempted to use a local pressing company, a large white company purchased the plant to keep him out. He was able to get a local studio to record, but had to send the master to a pressing plant located in Port Washington, Wisconsin to be pressed. Finally in about six weeks with all the preliminary work completed and all the necessary ingredients in place, from recording laboratories to wrapping paper and corrugated board. Pace was ready to manufacture Black Swan Records.

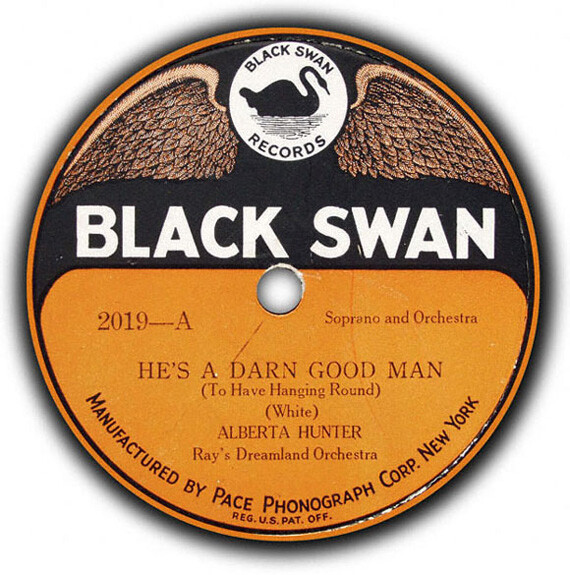

Pace used the name Black Swan to honor the accomplishments of Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield (1809–1976), a remarkably talented Negro singer known as “The Black Swan.” Pace had designed a logo, a handsome black and gold label with a swan in gold against the black, floating above the banner (Jazz: A History of the New York Scene). In his advertising in African-American newspapers Pace stressed the race issue, saying, “The only genuine colored records; others are only passing for colored.” Among the earliest employees for Pace was Fletcher Henderson, the pianist and band leader who became the recording manager and William Grant Still, the classical composer and orchestra leader who was the musical director of the new firm.

The first 3 records, probably recorded in April of 1921 and released in May of 1921, featured C. Carroll Clarke, a Denver-born baritone known to sing a fine ballad with a generally good reputation among high class Negro patrons, Katie Crippen, a vaudevillian who sang Blues and Revella Hughes, a soprano and vocal teacher who was very popular among the highbrow New York area patrons at that time. The Chicago Defender of May 7th, 1921 carried a press release of three paragraphs listing Black Swan 2001, 2002 and 2003 as May releases.

Fletcher Henderson was the pianist of record on all Black Swan releases from the start until the Fall of 1921. Other regularly used musicians for Black Swan during that period included: Joe Smith, Cornet; George Brashear, Trombone; Edgar Campbell, Clarinet; Cordy Williams, Charlie Dixon, Banjo; “Chink” Johnson, Trombone/Tubas. William Grant Still also doubled as manager and played several instruments (Oboe, Violin, Cello, Clarinet, Saxophone, Banjo and others) and was available for recordings.

Black Swan Records would have had a short and non-significant existence if it relied on the sale of its earliest records. Even Fletcher Henderson stated that these early releases were “straight songs or novelty numbers in the raggy style which was that heritage of the Europe–Bryman–Dabney School … the one blues had not been done in blues style. “The music was not being produced to appeal to the taste of masses of the African-American people. This changed suddenly in the Summer of 1921.

It was in the Summer of 1921 that Ethel Waters came to the rescue of Black Swan Records. Three different accounts of this occurrence are depicted. Whichever version we select the outcome was the same. Fletcher Henderson stated:

It was in the Summer of 1921 that Ethel Waters came to the rescue of Black Swan Records. Three different accounts of this occurrence are depicted. Whichever version we select the outcome was the same. Fletcher Henderson stated:

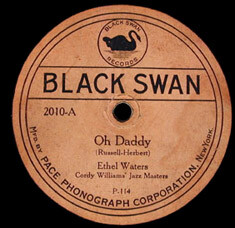

“I was walking along 135th Street in Harlem one night, and there, in a basement, singing with all her heart, was Ethel. I had her come down and cut four sides of which two—”Down Home Blues” and “Oh Daddy” —became such hits that we were made.”

Other recollections of this date are a bit different. Harry Pace himself was written:

Other recollections of this date are a bit different. Harry Pace himself was written:

“While in Atlantic City. … I went to a cabaret on the West Side at the invitation of a mutual friend who stated that there was a girl there singing with a peculiar voice that he thought I might use. I went into the cabaret and heard this girl and I invited her over to my table to talk about coming to New York to make a recording. She very brusquely refused but at the same time I saw that she was interested and I told her that I would send her a ticket to New York and return on the next Wednesday. I did send such a ticket and she came to New York and made two records, “Down Home Blues” and “Oh Daddy“. This girl was Ethel Waters and the records were enormously successful. I sold 500,000 of these records within six months. The next month I had her make two other records and thereafter for a long time she made a record a month. But none of them ever measured up to the “Down Home Blues” record.”

Ethel Waters added her own recollections. She had recorded earlier for the Cardinal company, having been contracted by a free-lanced talent scout, who later suggested she go to Black Swan for an audition:

“… I found Fletcher Henderson sitting behind a desk and looking very prissy and important. … There was much discussion of whether I should sing popular or ‘cultural’ numbers. They finally decided on popular, and I asked one hundred dollars for making the record. I was still getting only thirty-five dollars a week, so one hundred dollars seemed quite a lump sum to me. Mr. Pace paid me the one hundred dollars, and that first Black Swan record I made had “Down Home Blues” on one side, “Oh Daddy” on the other. It proved a great success … got Black Swan out of the red.

Riding the crest of this first successful Black Swan Recording, Pace and his small army hit upon the concept that would catapult Black Swan into the annals of recording history; the Black Swan tours.

High Times For Black Swan

It was ironic that at the time of its earliest success Black Swan had the opportunity to record and sign Bessie Smith, who would later become legendary as the “Queen of the Blues.” Harry Pace upon hearing her sing one night decided that she was too “nitty gritty” for his taste. (African-American Business Leaders, Ingraham and Feldman) Two years later she would break all sales as a Columbia recording artist.

The company was doing better by the fall of 1921. Pace decided to send a group of Black Swan artists out on a Vaudeville tour.

In the October 22, 1921 issue of the Chicago Defender there appeared the following advertisement:

“Coming Your Way—Black Swan Troubadours Featuring the Famous phonographic Star ETHEL WATERS The World’s Greatest ‘Blues’ Singer and Her Black Swan Jazz Masters. Company of All-Star Colored Artists. Exclusive Artists of the Only Colored Phonograph Record Company. Lodge, Clubs Societies and Managers wire or write terms and open time. T. V. Holland, Mgr. 275 W. 138th St. New York City.

(Hendersonia/W. C. Allen)

An orchestra, the Black Swan Jazz Masters was organized to accompany Ethel Waters on this national tour. A man named Simpson was named road manager and a series of dates were lined up. But before the Tour could begin two matters had to be dealt with that reveal the social tone of the time, particularly in the world of African-American entertainment.

Fletcher Henderson, the well-mannered, quiet, studious pianist and leader of the Black Swan Jazz Masters, was being advertised on a National Tour with a noted Blues singer. From a distinguished Southern colored Georgia family, this Atlanta University chemistry graduate had to entertain his parents in New York City to counsel him before departing on the tour. After meeting Ms. Ethel Waters, the beloved Black Queen of stage, screen , T. V. and music had to suffer further indignities so she could enrich the legacy of Black Swan Records. She was requested and agreed to sign a one year contract with Harry Pace.

The Chicago DEFENDER of Dec. 24,1921 broke the news:

“ETHEL MUST NOT MARRY–SIGNS CONTRACT FOR BIG SALARY–PROVIDING SHE DOES NOT MARRY WITHIN A YEAR. New York, Dec. 21–Ethel Waters, star of the Black Swan Troubadours, has signed a unique contract with Harry H. Pace, which stipulates that she is not to marry for at least a year, and that during this period she is to devote her time largely to singing for Black Swan Records and appearing with the Troubadours. It was due to numerous offers of marriage, many of her suitors suggesting that she give up her professional life at once for domesticity, that Mr. Pace was prompted to make this step. … Miss Waters’ contract makes her now the highest salaried colored phonograph star in the country.”

The tour began at the Pennsylvania Standard Theater in Philadelphia on Nov. 23,1921 and the Black Swan Troubadours remained on tour until July of 1922. They visited 21 states (See Appendix) and performed in over 53 cities playing one or two night stands and up to 2 weeks on one engagement. (New Orleans)

The turnouts and enthusiasm of the audiences were fantastic. After the first month engagement, Pace hired Lester Walton, noted newspaper columnist (the first Black) for the New York World (a major daily newspaper) as the road manager and advance man for the Tour. Walton got the African-American Newspaper Network (New York Age, Chicago Defender, Pittsburgh Courier, Baltimore Afro-American) involved in pumping out constant media on the Tour and the people’s response to Ethel Waters and her Black Swan Jazzmen.

“ETHEL WATERS MAKING BIG HIT IN WEST Harry H. Pace, president of the Pace Phonograph Company, under whose auspices Ethel Waters and her troubadours are touring the West, received the following telegram from C. H. Turner, manager of the Booker Washington Theater, St. Louis, Mo., on Tuesday morning relative in her show, which opened there on New Year’s Day:

“Congratulations on your wonderful show which opened here today to a record business. Predict increase in sales of your product by thousand per cent.”

Miss Waters and her band has been making a hit in every theater she has played since beginning her tour. During the Christmas week her show was at the Lincoln Theater, Louisville, Ky.”

New York, Age, Jan., 7th, 1922

Early in January 1922, the Chicago DEFENDER noted that Lester Walton “manager in advance for the tour of Ethel Waters & Co.” had arrived in Chicago on Jan. 3, while the troupe itself was “breaking all records” in St. Louis. Undoubtedly he was lining up their next major playing date, for on Jan. 14, 1922, a prominent advertisement in the DEFENDER announced:

“One week Only—Starting on Monday, January 16. … Walton & Pace present the Black Swan Troubadours featuring Ethel Waters—World’s Greatest Singer of Blues and Her Jazz Masters, New York’s Leading Exponents of Syncopation. Also Ethel Williams and Froncell Manley in a Whirlwind Dancing Specialty. Grand Theater, State @ 31st St., Chicago. Nightly at 8:30.”

Chicago Defender, Jan. 14, 1922

“When the four musicians declared they were through, Miss Waters asked if there were others in the company who objected to traveling to the South. There were no response. The singer ended the incident by stating that while railroad accommodations and other phases of travel were none too desirable in the South she felt it her duty to make sacrifices in order that members of her Race might hear her sing a style of music which is a product of the Southland. The places of four dissatisfied musicians were at once filled by talented young men from Pittsburgh, St. Louis and Chicago.”

Chicago Defender, Feb. 11th, 1922

“ETHEL WATERS CO, NOW IN THE SOUTH

Ethel Waters and her Black Swan Troubadours opened their Southern tour Monday at the Palace Theater, Memphis, for a week’s run. Indications are that company will do a record-breaking business during this engagement. Company will open in Pine Bluff, Ark. for two days’ engagement of February 24 and 25, Fort Smith, February 27 and 28.”

New York Age, Feb. 18th, 1922

“ETHEL WATERS AND CO. A HIT IN NEW ORLEANS

New Orleans, La.—The Ethel Waters’ Company, Lester A. Walton, manager, of New York played a week’s engagement at the Lyric Theater of this city beginning Monday, April 17th, and offered a show that drew a record attendance at every performance for this playhouse. It has been voted the cleanest and strongest company of vaudeville performers offered at the Lyric in a long time. So popular as entertainers did it become after showing a few days that the New Orleans Item, a big daily here persuaded the manager to have the company’s star and its jazz band to go to its office on Friday night and have their work radio phoned all over the city and the surrounding territory. And on Saturday morning on the first page. The Item told its readers of the way the blues singer and jazz players stirred the radio fans by its hit. Friday night after the show, the Astoria Hotel had the company and manager as honor guests at a special entertainment in the Red Room of the Hotel. A toothsome collation was served the guests and the hall was thronged.”

New York Age, April 29th, 1922

“The dance at Lincoln Park Tuesday night (i.e. May 16) by Henderson’s Dance Orchestra of New York popularly known as Ethel Water’s Jazz Masters, was much better than expected. There was (sic) quite a few present in spite of the dampness caused by the rain, and all who went danced to the strains until the wee hours of the morning.”

Savannah TRIBUTE, May 18th, 1922

“The jazzies were present with bells on, and for the first time of their lives members of the […] his instrument […] than any musician [t]o ever appear—could do more with […] an excellent musician can do with a trombone—and few in the audience ever expected to hear the notes from a cornet that issued forth last night.”

Wilmington, N. C. TRIBUTE, unknown date

“The Wilmington, N. C., Dispatch had the following to say concerning the company’s appearance in that city: ‘Ethel Waters and her jazz masters have come and gone but their memory will linger for months. The Black Swan Troubadours played an engagement at the Academy of Music last night and were so much better than had been expected the crowd was left wide eyed and gasping with astonishment and delight for the company has class written all over it. Ethel Waters is headlined but was forced to share her honors with Ethel Williams, a dancer of more ability than two-thirds of those who have ever played Wilmington. Her acts, including shimmies and shivers, is done with Roscoe Wickman and it sent crowd into paroxyms of the wildest delight. The Williams woman is almost white, with her form of a Venus and the eyes of a devil and in company with Wickman, she lifted the audience up and up until it literally overflowed with delight. Ethel Waters’ blues numbers closed the program and with her jazz masters under perfect control and rendering jazz music that is only possible with Negro artists, she backed all colored competitors who have ever appeared here completely off the boards. The Waters aggregation is in a class to itself. It is so much better than other colored shows that have appeared here that a comparison is unfair to others.’

New York Age, June 3rd, 1922

The Tour was an overwhelming success with ramifications far and wide. Black Swan was established as an national record label with respect and increasing record sales. The new Blues and Jazz music had national recognition and a meaningful following. In New Orleans, Ethel Waters became the first Black performer to entertain on the new mass media, radio. Musicians like Louis Armstrong in New Orleans and Joe Smith in Cincinnati came out to support and perform with the Black Swan Jazz Masters. Anew camaraderie and standard was adopted within the National Jazz community.

The Tour was an overwhelming success with ramifications far and wide. Black Swan was established as an national record label with respect and increasing record sales. The new Blues and Jazz music had national recognition and a meaningful following. In New Orleans, Ethel Waters became the first Black performer to entertain on the new mass media, radio. Musicians like Louis Armstrong in New Orleans and Joe Smith in Cincinnati came out to support and perform with the Black Swan Jazz Masters. Anew camaraderie and standard was adopted within the National Jazz community.

By the time the participants in the Black Swan Troubadours returned to New York in July of 1922, the Pace Phonograph Co. had exploded in success. From its beginning in the basement of the owner, the company now owned a building as 2289 Seventh Avenue and 135th Street. It employed 15–30 people in its offices and shipping room, an 8-man orchestra, seven district managers in the largest cities in the country and over 1,000 dealers and agents in locations as far away as the Philippines and the West Indies.

In January of 1922, Harry H. Pace had issued a public financial statement on the first year of existence of Black Swan Records (New York Age, Jan. 24th, 1922). This strategy brought to the attention of everyone the financial success of Black Swan Records. A company started with $30,000 investment had yielded an income of $104,628.74 during its first eleven months of existence. That was almost four times the economic investment. Pace boasted that the success of Black Swan had colored people rewarded in the economic success of their labors:

“It is worthy to note that sharing in the prosperity of this company are colored employees, including singers, musicians, composers, printers an many other. The company announces disbursements for the period of […] $101,327.17.”

In April of 1922, Pace completed his final major deal when he bought part-interest in a pressing plant to produce Black Swan Records. He formed a partnership with John Fletcher, a white man, to purchase the bankrupt Remington Phonograph Corp. and their recording and pressing plant in Long Island City. With this increased capacity, Pace expanded the production of Black Swan Records to more than 6,000 records daily. Black Swan issued two new series of recorded music with its 10000 and 14000 series. With William Grant Still replacing the touring Fletcher Henderson, the company introduced music in every genre including opera, choral groups and symphony orchestras.

Things were going so well for Harry Pace that in an interview with writers for the New York Age in August of 1922, he talked about manufacturing a “Swanola” phonograph. He stated that this part of the business had not yet been fully developed. But the Pace Company was looking forward to employing colored mechanics as soon as they could be properly trained for work. This was Harry Pace’s final dream for Black Swan Records.

The Decline of Black Swan

If the success that Pace Phonograph Corp. Inc. experienced during its first year provided anything, it alerted the competition to the lucrativeness of the market. More than ever by succeeding years 1922 and 1923 obtaining Black artists became increasingly harder as the major white companies began to bid competitively for their services. After the tour concluded in July of 1922, artists like Fletcher Henderson and Ethel Waters no longer recorded exclusively for Black Swan Records.

The success of race records led to costly competition and price cutting by white-owned labels such as Okeh, Paramount and Columbia.

Many African-Americans, especially from the entertainment community, resented Pace for breaking his promise of an all-Black recording company. Though he continued to advertise that the enterprise was run only by Blacks and that they released recordings only by Black musicians, it was proven that the company was pressing records by white ensembles such as the Original Memphis Five. Pace began to lose the respect and confidence of the musician community and it became more difficult to continue to produce a quality product.

In March of 1923, the Pace Phonograph Company was renamed the Black Swan Phonograph Co., a sure signal that trouble was coming. By the summer on 1923, no new recordings of Black Swan were announced. Pace summed up his troubles in a letter sent to Roi Ottley:

Business became so great that we bought a plant in Long Island City that we were using as a recording laboratory and a pressing laboratory, and shortly afterwards transferred all shipping over to the plant. We were selling around 7,000 records a day and had only three presses in the factory which could make 6,000 records daily, … We ordered three additional presses in 1923 made especially for some improvements, and had them ready for installation in the factory. Before they were set up and ready for running, radio broadcasting broke and this spelled doom for us. Immediately dealers began to cancel orders that they had placed, records were returned unaccepted, many record stores became radio stores, and we found ourselves making and selling only about 3,000 records daily and then it came down to 1,000, and our factory was closed for two weeks at a time and finally the factory was sold to a sheriff’s sale and bought by a Chicago firm who made records for Sears & Roebuck Company. However, this did not completely defeat us and we continued to have records made at a concern in Connecticut and sold these repeat orders for a year or so until the thing finally came to a close.

In December of 1923, Black Swan Records declared bankruptcy and in May of 1924 Paramount announced a deal to lease the Black Swam catalog. Black Swan Records was history.

Pace Moves On

The long term impact of Black Swan Records are too numerous to elaborate upon fully in this paper. Some of them are:

- Paramount, Columbia and other recording companies could no longer ignore Black musicians and singers.

- The Black Swan discography still has value. As late as 1987, Jazzology Records announced its intention to revive the name and reissue the series of early recordings.

- Ethel Waters, Fletcher Henderson, William Grant Still, Alberta Hunter and many others used Black Swan as a training period and proceeded on to outstanding success within the entertainment industry.

It opened up the entertainment/recording industry to Blacks and opened up advertisement in Black newspapers from major record and entertainment companies. Today, the many musical, recording and entertainment stars who earn enormous salaries and have world-wide recognition owe a debt of gratitude to the symbol of self-pride and self-determination to The Black Swan Recording Company.

(Spring 1996 term paper for the “Black Music in New York City 1900–1935” graduate course in music at Brooklyn College.) –by Jitu K. Weusi

__________________________

Jitu K. Weusi (born Leslie R. Campbell; August 25, 1939 – May 22, 2013) was an American educator, education advocate, author, a community leader, writer, activist, mentor, jazz and art program promoter. He is one of the founders of the National Black United Front, Jitu Weusi Institute for Development, and the International African Arts Festival.

Reference Material Used

- Record Research—Black Swan catalog and discography 1955, 56, 57.

- Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans. Pages 366–367.

- Allen, W. C. Hendersonia—The biography of Fletcher Henderson. Pages 10–65.

- Waters, Ethel. His Eye is on the Sparrow.

- Jazz, A History of the New York Scene. Pages 166–167.

- Ottley, Leroi. The Negro in New York. Pages 234–238.

- Ingraham and Fletcher. African-American Business Leaders. Pages 510–517.

- New Grove Dictionary of Jazz. Pages 112–113.

- Sampson, H. T. African-American Culture and History. Page 369.

- Blacks in Blackfare. Pages 445–446.

- New York Age Newspaper Microfilm Jan. 1021 to Jan. 1924.

Redhotjazz.com was a pioneering website during the "Information wants to be Free" era of the 1990s. In that spirit we are recovering the lost data from the now defunct site and sharing it with you.

Most of the music in the archive is in the form of MP3s hosted on Archive.org or the French servers of Jazz-on-line.com where this music is all in the public domain.

Files unavailable from those sources we host ourselves. They were made from original 78 RPM records in the hands of private collectors in the 1990s who contributed to the original redhotjazz.com. They were hosted as .ra files originally and we have converted them into the more modern MP3 format. They are of inferior quality to what is available commercially and are intended for reference purposes only. In some cases a Real Audio (.ra) file from Archive.org will download. Don't be scared! Those files will play in many music programs, but not Windows Media Player.