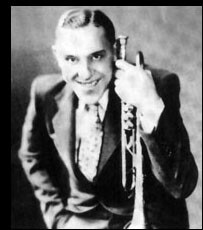

Wingy Manone had an appealing image of a happy intuitive musician, a primitive who one day woke up and started playing the trumpet for the fun of it, always having a good time performing New Orleans jazz. While the latter was certainly true and his on-stage joking and jiving along with his trumpet playing always sounded natural and spontaneous, Manone first had to overcome some personal tragedy.

Wingy Manone had an appealing image of a happy intuitive musician, a primitive who one day woke up and started playing the trumpet for the fun of it, always having a good time performing New Orleans jazz. While the latter was certainly true and his on-stage joking and jiving along with his trumpet playing always sounded natural and spontaneous, Manone first had to overcome some personal tragedy.

He was born as Joseph Matthews Manone in New Orleans on February 13, 1900; his last name has sometimes been misspelled as Mannone. When he was ten, he was involved in a horrific accident that resulted in his right arm being completely crushed when it was caught between two streetcars. His limb was amputated and replaced with a prosthetic arm. Manone eventually became so adept at utilizing his new arm that few in his audiences ever noticed his disability. Due to his situation, he was soon given the lifelong nickname of “Wingy” but otherwise he rarely mentioned the missing arm. Typically, violinist Joe Venuti made a joke of the whole thing in later years, giving Manone the same Christmas present every year for decades: one cuff link.

Growing up in New Orleans and constantly surrounded by music, it is not surprising that Manone soon began learning the cornet (switching to trumpet in 1928) since it was one of the very few instruments that can be played one-handed. He developed quickly and was a professional musician by the time he was 17. Manone performed on riverboats on the Mississippi River, worked regularly in his home town, toured the South (including working with the legendary pianist Peck Kelley in Texas) and California, and was a member of the Original Crescent City Jazzers in St. Louis. That group changed its name to the Arcadian Serenaders by the time Manone made his recording debut with the sextet on November 29, 1924. He already had a powerful sound and a lively style (as heard on “Fidgety Feet” and “San Sue Strut”) although it would be a few more years before he was truly distinctive.

Manone worked with many different bands during the next decade. He recorded one released title in 1926 (“Mother Me, Tennessee”) as the leader of the San Sue Strutters. The following year he led a fine session in New Orleans that included his first vocals: “Up The Country Blues” and “Ringside Stomp.” Manone spent part of 1927 in New York. He was already highly rated by other musicians and on September 16, cornetist Red Nichols used Manone on a record date to play a few hot breaks on “Baltimore.” Manone’s crackling sound and impeccable timing showed that by then he had developed his own personal style, one that would be heard on a countless number of sessions during the next few decades.

The 1928-33 period found Manone quite busy as a freelancer including working with Ray Miller, Charlie Straight, and Speed Webb. During 1928-30 he recorded with Benny Goodman’s Boys (playing next to Goodman, tenor-saxophonist Bud Freeman and pianist Joe Sullivan), the Cellar Boys (two numbers with Freeman and clarinetist Frankie Teschemacher), and a few sessions with Red Nichols as part of a trumpet section that included Nichols and Charlie Teagarden. In addition, he led record dates (sidemen included Teschemacher, Freeman, Gene Krupa, and pianist Art Hodes) during which he took vocals during eight of the numbers. On the instrumental “Tar Paper Stomp” in 1930, Manone introduced the riff that would, though several incarnations (Horace Henderson’s “Hot and Anxious,” Joe Garland’s “There’s Rhythm in Harlem”), ultimately become the basis for Glenn Miller’s “In The Mood” nine years later.

All of this was a prelude, and Wingy Manone was off records altogether during the Depression years of 1931-33. 1934 was his breakthrough year. He settled in New York, found musical homes at the Hickory House and the Famous Door on 52nd Street, and began to become quite popular. During the next seven years, Manone recorded 147 songs without counting alternate takes, performances that were released many decades later, or the six-part “Jam And Jive” from 1941. Although it would soon be the big band era, Manone went the opposite way, heading a three-horn four-rhythm septet. His repertoire included New Orleans jazz classics, swing tunes, novelties, and pop songs. However, as with Fats Waller and Louis Prima from that era, the material did not matter as much as his treatments. Nearly every selection that he recorded included a likable good-time vocal by the gravelly-voiced Manone (who was influenced by Louis Armstrong without directly copying him), solo space for the other horns, and some of the leader’s hot trumpet. This was the type of music that many Louis Armstrong fans wish he were recording during the swing era.

While New Orleans jazz was considered out of vogue during a period when big bands dominated American popular music, Manone predated the New Orleans revival by several years. He was greatly helped out by having a hit record with “The Isle Of Capri.” Recorded March 8, 1935, several months before Benny Goodman’s great success launched the swing era, Manone turned the sentimental ballad into heated jazz.

While New Orleans jazz was considered out of vogue during a period when big bands dominated American popular music, Manone predated the New Orleans revival by several years. He was greatly helped out by having a hit record with “The Isle Of Capri.” Recorded March 8, 1935, several months before Benny Goodman’s great success launched the swing era, Manone turned the sentimental ballad into heated jazz.

While not all of his recordings from this busy period were of the same quality, virtually all of them are enjoyable; Manone’s good humor was always difficult to resist. In addition to his regular bandmates, who were talented if not household names, some of Manone’s recordings utilized such sidemen as tenor-saxophonists Eddie Miller, Bud Freeman and Chu Berry, clarinetists Matty Matlock, Joe Marsala and Buster Bailey, and trombonists Santo Pecora, George Brunies, and Jack Teagarden. His session from August 15, 1934, which went largely unreleased at the time, not only included clarinetist Artie Shaw, trombonist Dicky Wells, and Bud Freeman, but two songs apiece with either Teddy Wilson or Jelly Roll Morton on piano; those were Morton’s only recordings from the 1931-37 period.

Among the highlights of Manone’s records are such numbers as “Royal Garden Blues,” “Zero,” “You Are My Lucky Star,” “I’m Shooting High,” “I’ve Got My Fingers Crossed,” “Dallas Blues,” “Swing Me A Swing Song,” “Panama,” “Corrine Corrina,” “Stop The War (The Cats Are Killing Themselves),” and even “Oh Say, Can You Swing?” Manone also recorded with a 1934 version of the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, Russ Morgan (featured on “Slip Horn”), Gene Gifford (as a singer on two songs), and Adrian Rollini’s Tap Room Gang.

In 1940, Wingy Manone moved to Los Angeles. He had a prominent role in the Bing Crosby film Rhythm On The River and was friends with Crosby for many years. He sometimes appeared as a comical character on Crosby’s radio shows, building upon his image of a primitive genius who loved to play trumpet. Manone also appeared in small roles (sometimes cameo appearances) in such films as Beat Me Daddy Eight To The Bar (1940), Juke Box Jenny (1942), Hi’ya Sailor (1943), Trocadero (1944), Sarge Goes To College (1947), and Rhythm Inn (1951) in addition to starring in a few Soundies.

The 1940s found Manone maintaining his popularity and playing in an unchanged style that was not affected in the slightest by the rise of bebop and rhythm & blues. He debuted his most famous original, “Tailgate Ramble,” in 1944 with lyrics by Johnny Mercer; it has since become a Dixieland standard. Manone wrote his memoirs Trumpet On The Wing which was published in 1948 when he was still just 48 and at the peak of his playing and popularity.

He also continued recording, although not quite as extensively as during the previous decade, including as a leader (one session was billed as being by Wingy Manone and his New Orleans Buzzards) and with Nappy Lamare, Eddie Miller, and Jack Teagarden in addition to occasionally working with Eddie Condon.

But since Wingy Manone did not make any attempts to evolve or modernize his style, eventually the music world passed him by. There were no major hits after “Isle Of Capri” and in the 1950s he was thought of as a figure of the past. During 1950-55 Manone recorded a total of ten songs and his versions of such tunes as “Riders In The Sky” (from 1949), “Vaya Con Dios,” “Three Coins In the Fountain,” and “Oh, Capri” were far from best sellers. His one minor hit took place in 1957 when he recorded his first full-length LP, Trumpet On The Wing. Manone’s version of the rock and roll song “Party Doll” actually made it to No. 56 on Billboard’s pop chart. But that was just a fluke.

Wingy Manone moved permanently to Las Vegas in 1954. He regularly touring the US and starting in the 1960s he occasionally Europe, playing at jazz festivals and clubs. His 1959 album for the Imperial label The Wildest Horn In Town (the title was an attempt to capitalize on Louis Prima’s fame) has some heated trumpet playing along with his good-time vocals but there would be only a few other highpoints during his final 20 years. Other late period records worth searching for are 1962’s On The Jazz Band Bus (Imperial) and his matchup with Papa Bue’s Viking Jazz Band in Copenhagen during 1966-67 for the Storyville label (A Tribute To Wingy Manone).

While Wingy Manone’s playing abilities gradually declined from then on, his enthusiasm and the happiness that he expressed whenever he was onstage were undiminished. He appeared at a 1974 Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Festival with the Davenport Jazz Band and made his final recordings in Italy in 1975, performing “Isle Of Capri” one last time.

One cannot imagine that Wingy Manone was enthusiastic about fading out of the music scene in his last years since he loved making audiences happy while playing his brand of swinging New Orleans jazz. He passed away on July 9, 1982, at the age of 82.

Wingy Manone’s best early recordings have been reissued in several ways including on the out-of-print six-CD Mosaic box set The Brunswick and Vocalion Recordings of Louis Prima and Wingy Manone (1924-1937), the four CDs in Collector’s Classics’ The Wingy Manone Collection Vols. 1-4 (which also goes up to 1937), and three CDs from the French Classics label: 1937-1938, 1939-1940, and 1940-1944 (Classics 1091). His music is a constant joy that is well worth discovering.

Since 1975 Scott Yanow has been a regular reviewer of albums in many jazz styles. He has written for many jazz and arts magazines, including JazzTimes, Jazziz, Down Beat, Cadence, CODA, and the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, and was the jazz editor for Record Review. He has written an in-depth biography on Dizzy Gillespie for AllMusic.com. He has authored 11 books on jazz, over 900 liner notes for CDs and over 20,000 reviews of jazz recordings.

Yanow was a contributor to and co-editor of the third edition of the All Music Guide to Jazz. He continues to write for Downbeat, Jazziz, the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, the Jazz Rag, the New York City Jazz Record and other publications.