In 1991, I had been chasing the music of Joe “King” Oliver and Louis Armstrong for seven or eight years. By “chasing,” I mean I was after the heart of it, the life at the center. Louis’ Hot Five records from the mid-twenties had always seemed radical to me, the music and swing breaking upward through concrete and making trees sway. It made me sway. And Armstrong’s early musical direction had been set, in part, by his New Orleans mentor, Joe Oliver.

That summer, I decided to follow the route Joe Oliver and his band had taken during 17 months of traveling, from February 1934 through June 1935. The tour had covered 11 southern states, not to mention points in Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Michigan. The whole itinerary, including the town names, rates of pay, and racial makeup of each audience (notated as “W” or “N”) had appeared in a log kept by Paul Barnes, an Oliver sideman and one of his best friends on this road trip.

During this time, the Oliver band did some 297 one-night stands. The musicians each earned anywhere from a top evening rate of $6.35 down to zilch. Sometimes they were stiffed or run out of town. When it came to housing and food, they mostly had to fend for themselves. They put up with broken down busses and cheating agents, sometimes finding themselves stranded without work at some southern crossroads, the bands breaking up on the road.

It was Joe Oliver’s swan song. Twenty years earlier, his cornet had ruled New Orleans. He had played with the best bands and made the biggest noise.

The late Edmond Souchon reminisced that he was “fortunate enough to hear the great Joe Oliver blasting the heavens and shaking the blackberry leaves in funeral parades….” Mutt Carey, whose Crescent City musical career sidetracked Oliver’s, said that “Joe could make his horn sound like a holy-roller meeting; God, what that man could do with his horn!”

On Chicago’s South Side during the twenties, Oliver had played to packed, dancing crowds at the major black & tans—the 800-seat Dreamland, the famed Lincoln Gardens Cafe, the Plantation Café. His bands attracted the hottest of the New Orleans players—Johnny Dodds, Baby Dodds, Kid Ory, Bill Johnson, Paul Barbarin, Luis Russell, Albert Nicholas, Barney Bigard, and Louis Armstrong—all of whom had been around when jazz was getting on its feet.

Oliver pulled like a magnet. Bubber Miley, the great Ellington growler, sat open-mouthed in 1921 listening to the “King” at the Dreamland. A 14-year-old Benny Goodman, along with his Austin High School friends, showed up in 1923 to hear King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band at the Lincoln Gardens. Another observer at the Gardens, the drummer George Wettling, said,

Unless you were lucky enough to hear that band in the flesh you can’t imagine how they played and what swing they got. After they would knock everybody out with about forty minutes of High Society, Joe would look down at me and wink and then say, “Hotter than a forty-five.”

When in 1923 King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band went into the Gennett Studios in Richmond, Indiana and stood Louis up for his first-ever recorded solo—on “Chimes Blues“—American music would change forever.

But somewhere between 1925 Chicago, IL and 1935 Cairo, IL—the first stop in Barnes’ log—Oliver’s flame had become an ember. It may have been his 1918 uprooting from New Orleans. The Crescent City cornetist Johnny Wiggs reminisced,

When Joe Oliver left New Orleans he left his original style behind. I don’t know what happened to him, but none of his records… sounds anything like the Joe Oliver in New Orleans. None of his other records, including the Creole Band sides, give the slightest trace of early Joe Oliver.

Other eyewitnesses—Louis included—have agreed.

At any rate, Joe Oliver had fallen from grace, or at least popular opinion might have thought so.

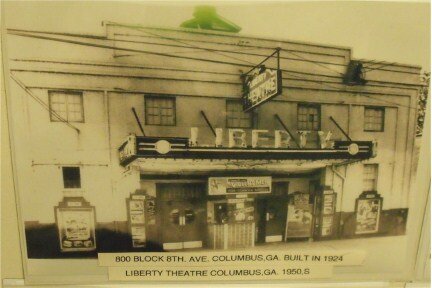

I did not have 17 months to find out, so I decided on just three towns from Oliver’s March, 1935, itinerary: Gadsden, Alabama; Columbus, Georgia (the Liberty Theatre); and Moultrie, Georgia. I contacted AAA headquarters in Florida. Amazingly, they had maps going back to 1935. The maps revealed exactly the route the band must have taken at that time—there was no other way.

I dropped off the interstate a few leagues from Gadsden, which lies around 70 miles northeast of Birmingham. Suddenly I found myself on a cracked country blacktop, high weeds leaning at the shoulders, overgrown trees draped over the road. I felt I had just dropped out of the present.

It didn’t take long to know that I had. In about two miles I rounded a bend and found myself looking at a deserted dirt lot, the kind that could have turned into a garbage heap, which in a way, it had. Filling this lot, as though it were an automobile graveyard, was a collection of abandoned buses, the old kind with the curved (“streamlined”) back ends. Their windows were filthy, and their tires were low or flat. No one was around, and it looked like no one had been. At the front of the lot, near the road, was a hand-painted sign: “Band busses for rent.” I looked twice. For all I knew, the lot vanished the moment I left.

I drove into Gadsden without knowing what I was looking for, and I pretty much left the same way. Even though I had come out of the cultured Northeast, I had acted the rube, having done not a lick of preparation for this trip. I thought I would just “follow the route,” as though I would find Joe Oliver standing on a corner somewhere (he had died in 1938).

I clunked through the small city during a crowded weekday dusk, crossing the Coosa River on one of the old iron bridges, wondering what I had expected to find. Alone in a strange town, I got a little scared. What if I found—nothing?

The next day, in route to Columbus, GA, I went through Anniston, AL. Somewhere behind the hill lay Fort McClellan, where my late father had trained during WWII. I guess I was retracing his route as well as Joe Oliver’s. I would never know the thousand stories of my dad’s young life.

South of Anniston on interstate 431, I passed a couple of old horses chewing grass in front of somebody’s shack. The roof sagged, like an old mattress, and the horses’ backs did the same.

At Columbus, things started looking up. From Paul Barnes’ log, I knew that the Oliver band had played the Liberty Theatre in March of 1935 (56 years earlier), so I started digging. A local reporter went through some files for me and personally escorted me to the Liberty—still standing and under renovation—where he introduced me to Roscoe Chester, an educated man and local historian involved with the restoration.

At Columbus, things started looking up. From Paul Barnes’ log, I knew that the Oliver band had played the Liberty Theatre in March of 1935 (56 years earlier), so I started digging. A local reporter went through some files for me and personally escorted me to the Liberty—still standing and under renovation—where he introduced me to Roscoe Chester, an educated man and local historian involved with the restoration.

Beginning in 1924, the Liberty for 50 years had been Columbus’ principal venue for black entertainment. Names like Ethel Waters, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Fletcher Henderson, and the Chick Webb band with Ella Fitzgerald had played the Liberty. The great Ma Rainey, born and raised in Columbus, had performed there—as well as her protégé Bessie Smith. And in March, 1935—Joe “King” Oliver.

The Liberty had been segregated, Mr. Chester told me, with whites on one side of the aisle, blacks on the other, and a rope down the middle. “If the rope were to disappear, it wouldn’t have made any difference,” he said. “It’s a mental block. It never left the black mind—that I’m over here, and Mr. Charlie’s over there.”

Mr. Chester also told me that “Silas Green from New Orleans” had played the Liberty. After a little digging of my own, I learned that this act had been a traveling tent show that had toured the South continually from 1904 into the 1940s. At one point, the all-black show featured 54 performers including a 16-piece band and 16 girls. In an amazing connect to the future, the avant-garde jazzman Ornette Coleman played with the Silas Green show when he was just starting out.

After some talk, Mr. Chester allowed me inside the temporarily closed venue. In the dark, past the construction gear and disconnected rows of seats, I could see the stage glimmering in shadows and imagine echoes of the music.

The road to Moultrie brought me into Georgia farmland—orchards, home-grown tomatoes and other fresh-picked produce, big trees. I drove through Parrott, GA, population 222, where the old frame houses with picket fences looked original—the same ones Joe Oliver would have seen passing through to Moultrie that March day. Unbeknownst to Oliver, a 10-year-old Jimmie Carter would have been growing up in Plains, just 15 miles away.

In Dawson, I saw the red brick city hall with its steeple, clearly out of the 1800s. Then the road turned into a straight, narrow line running through farm country, way off into the distance.

I had no idea what Moultrie would be like. Outside of Barnes’ log, I had never heard of it, so I thought it would be just a speck on the map, a one-horse town where nobody knew nothin’ about nothing. Talk about Northern ignorance!

Moultrie, it turned out, bustled with feed businesses, farm machinery outlets, grain stores, warehouses, and lumber yards. The old Central Georgia Railroad ran through it, and after 1900, the area had turned into a farmer’s heaven. Yet it took its name from General William Moultrie, a Revolutionary War hero—appropriate for Joe Oliver’s revolutionary music.

Clueless about where to start, I headed for the public library where I read through old local newspapers. I found nothing about Oliver. I was surprised to see that the library had a well-stocked genealogy division, so I started digging around in there. Still nothing.

Then I spoke with one of the librarians, Ms. Elois Matthews. I explained what I was doing. She listened, thought a minute, then said, “Hold on.” She went to the telephone.

Two calls later she came back. “Call these two men,” she said. “I think they were around back then.”

My blood pressure rose and my hairs stood on end. I made the first call.

Within an hour I was driving through Moultrie with John W. Whitaker, a retired railroad trainmaster who had lived most of his life in this town. He had been 13 or 14 when Joe Oliver passed through. But at his young age, he had been unaware of the dance concert.

Mr. Whitaker had caught the business end of a Jim Crow society. As a young man he had shoveled coal on the railroads, then volunteered for the Air Force. With what must have been the same kind of gumption that Joe Oliver showed, he became one of the famed Tuskegee Airman and flew B-25s during WWII. He returned to Moultrie after the war and applied for a promotion on the railroad—to engineer. They turned him down, telling him he was unqualified.

“At that time, a B-25 cost five and a half million dollars,” Mr. Whitaker told me, “and I was in charge of it. But ‘You can’t run this train.’”

The white railroad brotherhood came down on him, and even his black friends wouldn’t speak to him. But he finally got his promotion 20 years later, following the passage of the 1963 Civil Rights Act.

“I ran my first train from Albany to Columbus, September 3, 1963,” he said, “and you would have thought Ringling Brothers’ Circus was coming through all those towns.”

Speaking of Joe Oliver, he added, “I’ve always said that if any brotherly love or any brotherhood or any mixing ever came about, it would come through music.”

Mr. Whitaker had shown me the town. When he dropped me back at the library, I made the second call—to a Mr. E. J. Starkey. I told him what I was doing.

“I actually saw Oliver when he was here,” Mr. Starkey said.

If I was excited before, I think this time I almost lost consciousness.

Mr. Starkey had been born in Moultrie in 1915 and had been 19 when Oliver barnstormed through in 1935, during the Depression. He couldn’t afford tickets, but he was a music student, and he knew the booker.

The dance had been a packed house. It happened in Moultrie’s old “Royal Garden” dance hall on “Rat Row,” above Mattie Barnett’s drug store. The venue had taken its name from the original Royal Garden in Chicago’s South Side, where Oliver had played, and after which Clarence Williams had titled his jazz evergreen, “Royal Garden Blues.” [Wolverine’s Version linked.]

To get into the Rat Row venue, you had to climb a flight of stairs on the side of the building. Oliver’s band had drawn 500 people that night. I asked Mr. Starkey if it had been a big deal for him.

“What you talkin’ about!” he responded. “A big deal for Moultrie, for a fact.”

I kept asking questions.

“It was a large, open dance hall, along with the stage,” Starkey told me. “When you come in, the man take your ticket, and they have a little vestibule. When the school would have their annual play, a musical or something, they’d have it up there.”

But that night, it was serious music. “If they didn’t go to it when old Oliver was there! People came from all over. We’d draw from Thomasville, Albany, the adjoining towns.” Posters would go up on telephone poles and brick walls, Starkey told me. “The whole town would go for the thing, just like a stampede crowd.”

Barnes’ log indicated that the Moultrie crowd was a Negro one (“N”), and primarily it was. But white folks came, too.

“Of course, at that time, the South was rough. But the white collar people would go down there and buy tickets,” Starkey said. “Them fellas, those type fellas, they didn’t give a rat damn. Because those bands had something they wanted. Especially King Oliver. They paid whatever fare was to be paid and they would go on up. And some of them would bring their women.”

What was the music like?

“It was dance music,” Starkey told me, “all dancing. This concert business came later on. It was the slow drag, the two-step, the breakaway, and the Lindberg Fly. One of the instrument players would take the solos and the lyrics—that’s the way he had it organized. Like blues. And it was before microphones—they didn’t have all this electrified stuff. They would sing through a horn. It was jazz, blues, and every now and then, ‘Mood Indigo’—all that contemporary stuff. Sometimes they’d request ‘Danny Boy’ or ‘Stardust.’ He was nice about requests. He would try to get everybody’s request.

“And they was reading. They had everything setting in front of them. Back in them days they looked real intelligent, knew what they were doing. They wore uniforms, every one of them.”

What E.J. Starkey would not have known was that, by the end of 1935, Joe Oliver would own just one wearable suit of clothes, that gum disease would render him unable to play, and that just two and one-half years later he would die alone and broke in Savannah.

In those days, there was little press about jazz, particularly in small towns. The first American jazz magazine, Down Beat, didn’t appear until 1934. In the June, 1936, issue of that publication, the late jazz journalist Marshall Stearns noted,

In evaluating the contribution of the American Negro to swing (jazz) music, a contribution which is the most important single element of the phenomenon, it should be remembered that, for many years, due to racial prejudices which still exist in part today, recognition was only given to white musicians, no matter what kind of music they played.

So when Oliver played Moultrie in 1935, he was a black cinder in the night. He would die in obscurity. There was not even enough money to purchase a headstone.

But for E.J. Starkey, in no way had Joe Oliver fallen from grace. The old Royal Garden was gone, but Starkey remembered:

“It’s an empty lot now. But I can recall it. I can hear them sounds in my ear. Good stuff. (He sings:) ‘Hold that tiger.’ Wonderful music. The manager, he would always have a big pitcher of nice refreshment—lemonade or what have you. And that good moonshine too. Get you a small 6 ounce and a half bottle of—that small Coca Cola—get that full of good Georgia moon, you didn’t want nothin’ else but your gal, and that music.”