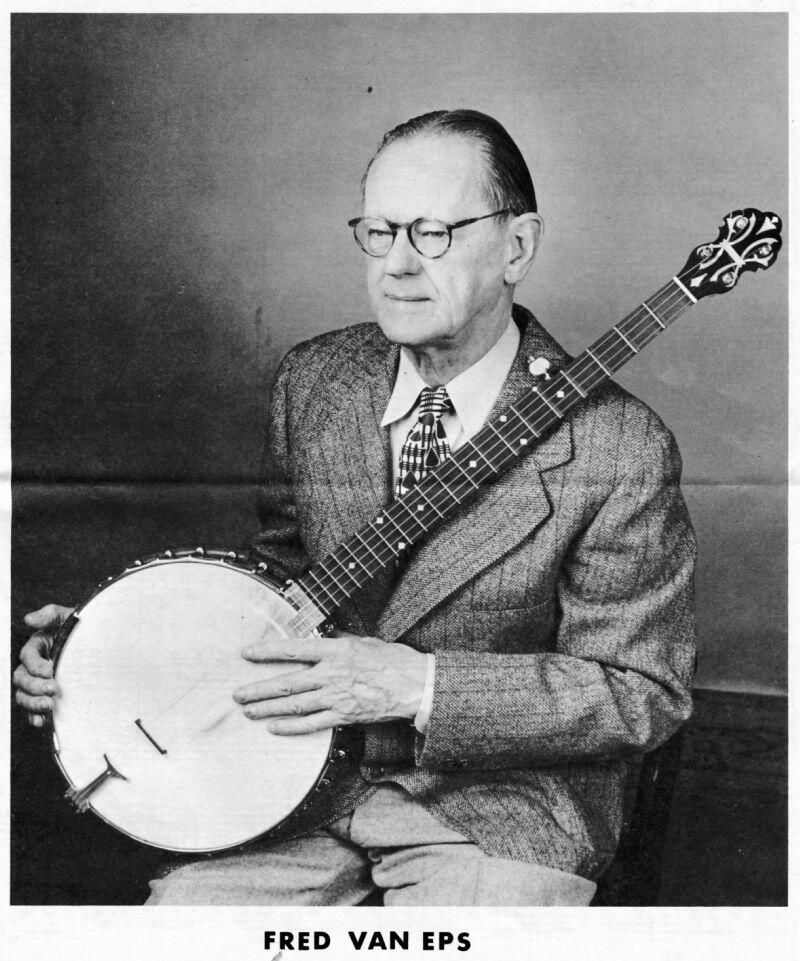

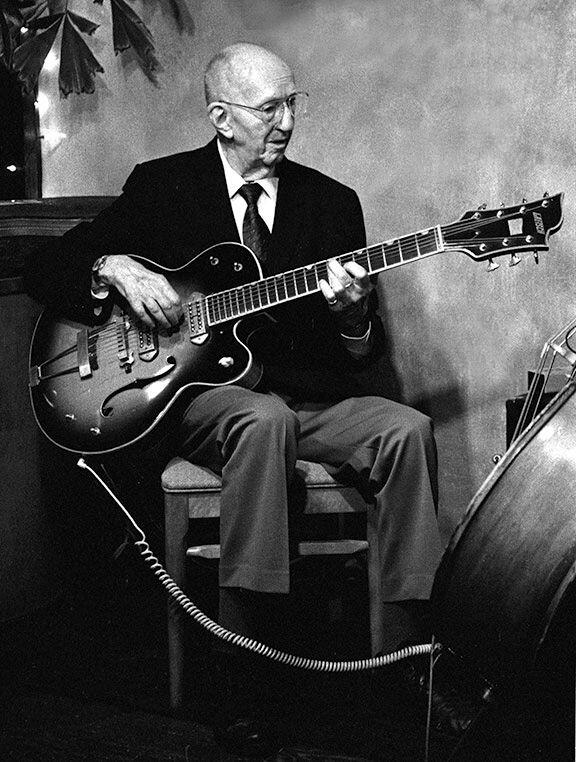

Banjoist Fred Van Eps cut his first released recordings in 1897 while his son, guitarist George Van Eps, made his final recordings in 1997, a century later. They both left behind important musical legacies.

Frederick Fletcher Van Eps was born December 30, 1878 in Somerville, New Jersey. From the age of seven, he studied the violin. But by the early 1890s, Van Eps had become much more interested in playing popular music and the banjo. In contrast to his classical training on violin, he just took informal banjo lessons from a conductor on the Jersey Central Railroad (George W. Jenkins) who taught him fingerings and songs. Van Eps developed quickly and, when he discovered some of the recordings of Vess Ossman, the leading banjoist of the time, he learned Ossman’s solos by playing his cylinders over and over again.

Vess Ossman (1868-1923) made his first recordings in 1893 and was famous for his recordings of cakewalks, marches, and ragtime. In the early days of recording, the banjo was quite popular because it could be picked up easily by the primitive recording equipment. While cornets, singers, and tubas also fared well, guitars and string basses were mostly inaudible and the piano did not record well either. The result was that, during the ragtime era, there were many more recorded banjo features on rags than piano showcases.

Soon after discovering Ossman, Van Eps made his first recordings on his own cylinder machine, experimenting with creating home recordings on blank cylinders. While he worked at his father’s jewelry and watchmaking business, dropping out of school when he was 15, Van Eps practiced the banjo every chance that he had. In 1897 he made his move. The 18-year old went to the Edison Company with a pair of his home recordings, and soon got a job as a staff musician for the Edison label. The work proved to be quite lucrative and much more fun than working as a watch maker.

Soon after discovering Ossman, Van Eps made his first recordings on his own cylinder machine, experimenting with creating home recordings on blank cylinders. While he worked at his father’s jewelry and watchmaking business, dropping out of school when he was 15, Van Eps practiced the banjo every chance that he had. In 1897 he made his move. The 18-year old went to the Edison Company with a pair of his home recordings, and soon got a job as a staff musician for the Edison label. The work proved to be quite lucrative and much more fun than working as a watch maker.

Van Eps recorded up to a few dozen cylinders a day, often playing the same song repeatedly since the recording technology of the time only allowed a very small number of cylinders to be made from any one recording. Sometimes Van Eps would be asked to record Vess Ossman tunes when the label had run out of copies of the original recordings, and on some of those occasions, the newer recordings were actually issued under Ossman’s name since the older banjoist was too busy to recreate his own solos.

Van Eps made thousands of recordings during 1897-1926, not only for Edison but for such labels as Columbia, Victor, Pathé, Emerson, and Okeh. Not only does there not seem to be a complete and accurate discography of all of his recordings but, in the many decades since, relatively few of his recordings have been reissued and there is no definitive collection. (This is a job for Archeophone!) In the meantime, some of his recordings can be found on You Tube and throughout the internet.

While he played adaptations of classical themes, popular melodies, marches, and novelties, Van Eps also recorded jazzy and ragtime-oriented pieces including “A Bunch Of Rags,” “A Ragtime Episode,” “The Lobster’s Promenade,” “Dixie Melody,” “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” “The Junkman Rag,” “Down Home Rag,” “When Uncle Joe Plays a Rag On His Old Banjo,” and a version of “Maple Leaf Rag” from 1908. Not an improviser, Van Eps worked out his solos beforehand but always impressed listeners with his impressive technique and the feeling that he put into his playing.

Early in his career Fred Van Eps was featured in duets with pianist Frank P. Banta, with small combos, and occasionally with larger ensembles. By 1911 when he signed with the Victor label, Van Eps was becoming more famous and more in-demand than the legendary but gradually declining Vess Ossman (who stopped recording after 1917). Van Eps had hits with “The Burglar Buck” and “Rag Pickings” and in 1912 formed the Van Eps Trio, a unit that stayed active for a decade. Originally consisting of Van Eps, his brother Bill Van Eps on banjo and mandolin, and pianist Felix Arndt, when Arndt departed in 1915 (having had a giant hit with “Nola”), his first replacement was the young George Gershwin who unfortunately never recorded with Van Eps during his brief stay. Frank E. Banta, the son of Frank P. Banta, became the group’s permanent pianist. The executives at Victor insisted on replacing Bill Van Eps with a drummer but that was not the sound that Fred Van Eps wanted. By 1917 he had success replacing the drums with alto-saxophonist Nathan Glantz.

The Van Eps Trio (which became the Van Eps Specialty Four when they were joined by xylophonist Joe Green or the Van Eps Banjo Orchestra when they added a second banjoist) was prolific and popular. In 1921 the group starred in one of the very first sound film shorts, The Famous Van Eps Trio in a Bit of Jazz which I am hoping will show up someday, somewhere.

Van Eps went on extensive tours of the US and Canada during 1917-21 with an all-star group of recording artists which was called the Eight Famous Record Makers and later the Eight Victor Record Makers. Always interested in improving the sound of the banjo, in 1921 he formed the Van Eps-Burr Corp. with the manager of the all-star tours Henry Burr to manufacture and sell a banjo that he had designed. The company, which was soon under Van Eps’ sole control, lasted until 1930.

In the 1920s, Fred Van Eps was on the losing side of battles against jazz and the rise of the guitar. The improved recording techniques of the mid-1920s resulted in the acoustic guitar replacing the banjo by the early 1930s while ragtime had long since lost its popularity. Van Eps continued recording until 1927 including as a sideman with Nathan Glantz (his last recordings as a leader in the 1920s were “Dinah” and “I’m Sitting On Top Of The World” in 1926) but both his playing style and his instrument were considered out of vogue by the end of the decade. While Van Eps sometimes performed with bands in New Jersey and worked as a banjo instructor, he largely faded out of the music scene.

Fred Van Eps had four sons, all of whom became musicians. Fred Van Eps. Jr. (born in 1907) played trumpet, recording with such studio groups as the Varsity Eight, the Vagabonds, the Seven Blue Babies, the University Six, and Ted Wallace during the 1927-30 period. He later became an arranger for the Jack Teagarden big band of the late 1930s, Paul Whiteman, and on the Raymond Scott television show Your Hit Parade. Bobby Van Eps (born in 1909) was a pianist who recorded with Smith Ballew, Red Nichols (arranging “On The Alamo” for a 1929 session), Scat Davis, Paul Small, Freddy Martin (1933), the Dorsey Brothers Orchestra (1934-35), the Boswell Sisters, Jimmy Dorsey (1935-36 including sessions with Bing Crosby), and Matty Malneck along with a Red Nichols album from 1958. John Van Eps (born in 1911) played tenor-sax and clarinet with the big bands of Tommy Dorsey (1935), Ray Noble, Phil Lang, Larry Clinton, Jack Teagarden, Hal Kemp and Will Bradley; he was killed in a car accident in 1945.

While none of those Van Eps brothers were known as soloists or gained much fame, George Van Eps was on a different level. Born August 7, 1913 in Plainfield, New Jersey, he started playing the banjo when he was 11 but switched to the guitar the following year after hearing Eddie Lang play on the radio. He became a professional by the time he was 13 in 1926, performing on the radio and with Harry Reser’s Junior Artists and the Dutch Master Minstrels. By 1930, Van Eps was working in the studios, making his recording debut with Smith Ballew on a date that included his brother Bobby. He was a member of Freddie Martin’s big band (1931-33) and was part of the early Benny Goodman orchestra of 1934-35, choosing to stay in New York rather than go on Goodman’s historic road trip to California (Allan Reuss replaced him). But otherwise Van Eps was a studio musician during the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s.

From his earliest days, George Van Eps had the reputation of playing the most beautiful chords on the guitar. Part of the second generation of great jazz guitarists following Eddie Lang, Carl Kress and Dick McDonough, Van Eps was always in great demand for studio dates, helping to fill the gap caused by the premature deaths of Lang and McDonough. Following in the footsteps of his father who was a part-time inventor, Van Eps designed a seven-string guitar in 1938 (and a technique that he called “lap piano”) that made it easier for him to play bass notes simultaneously with melody lines and lush chords. In later years he would inspire Bucky Pizzarelli, John Pizzarelli and Howard Alden to take up and master the seven-string guitar.

In addition to his work with big bands (including Ray Noble) and anonymous studio orchestras, Van Eps was heard on some jazz sessions in the 1930s and early ’40s including with Louis Prima, Adrian Rollini, Red Norvo, Frankie Trumbauer, and singer Dick Robertson, occasionally contributing a brief chordal solo and always inspiring the other musicians with his playing.

He moved permanently to Los Angeles by 1944 and became not only a top West Coast studio guitarist but part of the local Dixieland scene, performing and recording with such groups as Matty Matlock’s bands, Charles Lavere’s Chicago Loopers, Floyd O’Brien’s State Street Seven, Bob Crosby, Eddie Miller, and the Rampart Street Paraders.

Those bands and other local groups had a lot of competition for Van Eps was also appearing on a huge number of movie sound tracks (including Pete Kelly’s Blues which resulted in the formation of the Pete Kelly Seven), commercials, and jingles plus studio dates for Capitol. Johnny Mercer utilized Van Eps often as did Peggy Lee and Paul Weston.

Meanwhile, Fred Van Eps, while largely forgotten during the swing era, was having great success as an inventor. He helped to advance recording techniques in the 1940s and made quite a bit of money when his innovations were adopted by the recording industry. With the comeback of the banjo in traditional jazz, Van Eps decided to try to make a modest comeback. In 1950, while accompanied by his son Robert on piano, he returned to the recording studio for the first time in 23 years. Van Eps recorded six numbers for his Five String Banjo label, showing that he could still play numbers such as “Maple Leaf Rag,” “Ragtime Oriole”, “Smiler Rag” and “Nola” with impressive technique and enthusiasm.

He also recorded a few other sessions including an album as late as 1956 although those sessions are quite obscure and did not create a stir. It is a real pity that he and his son George never recorded together because Fred’s banjo would have sounded glorious accompanied by George’s beautiful chords. Fred Van Eps passed away in Burbank, California on November 22, 1960 at the age of 81.

At that point in time, George Van Eps was not quite at the halfway point of his career. In 1949 he had recorded four numbers (“I Wrote It For Joe,” “Tea For Two,” “Once In A While” and “Kay’s Fantasy”) as a leader while accompanied by bass and drums along with a hot trio session with tenor-saxophonist Eddie Miller and pianist Stan Wrightsman. Among his many other record dates as a sideman were sets with Jess Stacy, Hoagy Carmichael, Frank Sinatra, the Kings of Dixieland and Wild Bill Davison. In 1956 Van Eps recorded a mood album of his own with strings called Mellow Guitar. In the mid-1960s he led a trio of melodic records for Capitol: My Guitar, Soliloquy (his only full album of unaccompanied guitar solos), and Seven String Guitar.

While George Van Eps remained very active throughout his life, he recorded very little during the 1970s and ’80s. During 1991-94 he teamed up with fellow guitarist Howard Alden (who was 45 years his junior) to co-lead three quartet albums for the Concord label: 13 Strings, Hand Crafted Swing, and Keepin’ Time. Also in 1994, George Van Eps recorded half an album of unaccompanied solos, a project called Legends that he shared with fellow guitarist Johnny Smith. Coupled with Keepin’ Time, that was Van Eps’ last significant recording.

The guitarist never really retired. I remember going to a Burbank club in the mid-1990s called Chadney’s where the noise and smoke level was generally so high that one could be ten feet away from the performing band and not be able to see or hear them! However when Van Eps performed recitals at the venue, the audience was so quiet that one could hear every beautiful note that he played.

George Van Eps passed away on November 29, 1998 at the age of 85, ending a century of classic music making by the Van Eps family.

Since 1975 Scott Yanow has been a regular reviewer of albums in many jazz styles. He has written for many jazz and arts magazines, including JazzTimes, Jazziz, Down Beat, Cadence, CODA, and the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, and was the jazz editor for Record Review. He has written an in-depth biography on Dizzy Gillespie for AllMusic.com. He has authored 11 books on jazz, over 900 liner notes for CDs and over 20,000 reviews of jazz recordings.

Yanow was a contributor to and co-editor of the third edition of the All Music Guide to Jazz. He continues to write for Downbeat, Jazziz, the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, the Jazz Rag, the New York City Jazz Record and other publications.