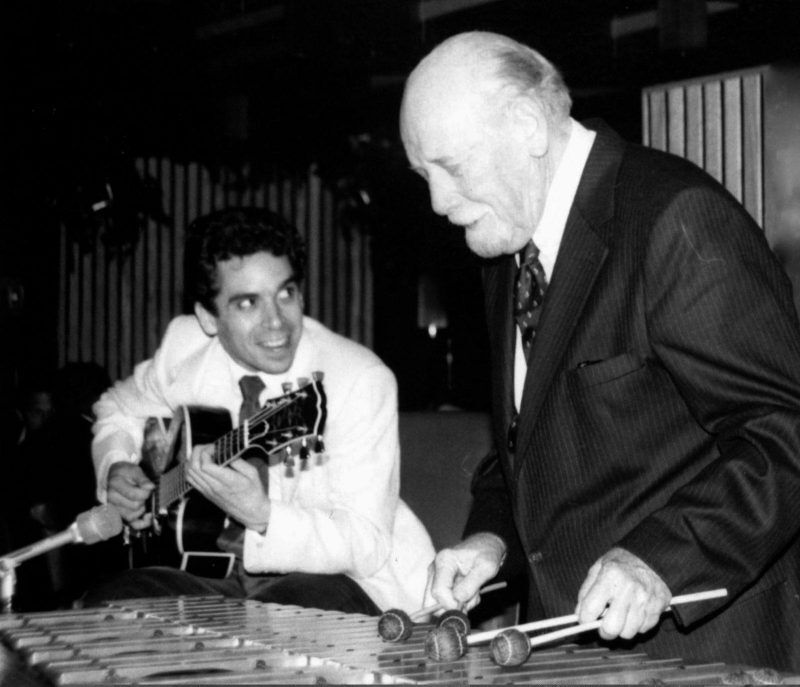

They were a bit of an odd couple. Red Norvo was thin and soft-spoken while Mildred Bailey was heavy and could be rather boisterous. But somehow the combination worked well for much of a decade, both musically and personally. Norvo was jazz’s first (and practically only) significant xylophonist while Bailey was one of the first non African-American female singers to make a strong impression on the jazz world.

Red Norvo was born as Kenneth Norville on March 31, 1908 in Beardstown, Illinois. He was originally a pianist, switching to xylophone and marimba as a teenager. In 1925 he toured with a marimba band called The Collegians. Norvo gained early experience playing xylophone with the orchestras of Paul Ash and Ben Bernie. He briefly left music to attend the University of Missouri as a mining engineer but music and show business proved to be too strong a pull. Norvo worked in vaudeville for a time as a tap dancer and on radio with Victor Young. In what looked like a big break, he joined the Paul Whiteman Orchestra in the early 1930s but he never recorded with Whiteman. However it was during that period that he met his future wife, Mildred Bailey.

Mildred Rinker is believed to have been born Feb. 27, 1900, in Tekoa, Washington; her birthdate was for years said to be 1907. A native American, she grew up near De Smet, Idaho, on the Coeur d’Alene Reservation. Her father played his fiddle at square dances and her mother was a pianist who encouraged her singing. When she was 17, she moved to Seattle where she worked at Woolworth’s as a sheet music demonstrator. She had a short-term marriage to Ted Bailey, keeping his last name,

While Ethel Waters and Louis Armstrong were influences, Mildred Bailey had her own sound from an early age. After touring with a revue, Bailey settled at first in Bakersfield, California (working at radio station KMTR) and then Los Angeles. Her second husband Benny Stafford helped her with her bookings. When her younger brother Al Rinker and his friend Bing Crosby dropped by in 1926 in hopes of also making it as singers, she helped them out, getting them jobs, most notably with Paul Whiteman where, with Harry Barris, they became the Rhythm Boys. Crosby returned the favor in 1929, arranging for Whiteman to hear her at a party.

When Bailey was hired, she became the first female singer to be regularly featured with a big band. She made her recording debut on Oct. 6, 1929 with a pickup group led by guitarist Eddie Lang and including some of Whiteman’s sideman (“What Kind Of Man Is You”). She also recorded another song with Whiteman sideman led by Frank Trumbauer (“I Like To Do Things For You” on May 8, 1930), two songs with clarinetist Jimmie Noone (“He’s Not Worth Your Tears” and “Travellin’ All Alone” from Jan. 12, 1931), and led her first record date (Sept. 15, 1931), performing four fine songs while backed by the Casa Loma Orchestra.

Bailey did not get around to recording with Paul Whiteman until Oct. 4, 1931. There were a few sessions with Whiteman most of which are now obscure although her version of “All Of Me” in 1932 was a bit of a hit and her rendition of “I’ll Never Be The Same” is superior ballad singing. On her own record session of Aug. 18, 1932, Bailey recorded her first version of “Rockin’ Chair.” Rather than taking it as a humorous duet (which was how Louis Armstrong did it), Bailey sang the song as a sentimental ballad. That success led to her getting the nickname of “The Rockin’ Chair Lady.” She also helped to popularize “Georgia On My Mind.” But in general Mildred Bailey’s three years with Whiteman were largely uneventful beyond the fact that she met Red Norvo. They were married in late-1933.

Despite being with Whiteman for two years, Norvo was completely undocumented on recordings with the bandleader. In fact, as 1933 began, his only recordings had been two songs (including Bix Beiderbecke’s “In A Mist”) from Oct. 1929 that were never released, and participation on some radio transcriptions with Frank Trumbauer in 1932 that were not made available until the LP era.

Despite being with Whiteman for two years, Norvo was completely undocumented on recordings with the bandleader. In fact, as 1933 began, his only recordings had been two songs (including Bix Beiderbecke’s “In A Mist”) from Oct. 1929 that were never released, and participation on some radio transcriptions with Frank Trumbauer in 1932 that were not made available until the LP era.

For both Norvo and Bailey, 1933 was really the beginning of their careers, particularly on record. In addition recording with arranger-composer Victor Young, Norvo led his first sessions that year. Prior to Norvo, there were virtually no significant xylophone soloists in jazz. Charles Hamilton Green and his brother Joe Green had appeared on quite a few sessions in the 1920s as studio musicians but, despite their virtuosity, their playing was really outside of jazz. The Chicago drummer Jimmy Bertrand occasionally played xylophone but he never really focused on the instrument nor took a memorable solo.

Norvo’s first date as a leader (April 8, 1933) was comprised of a pair of features for his xylophone and marimba (“Knockin’ On Wood” and “Hole In The Wall”) with backing by a rhythm section and clarinetist Jimmy Dorsey. His second session for the Brunswick label was more controversial. When Jack Kapp, the head of Brunswick, was out of town, Norvo gathered together a quartet (guitarist Dick McDonough, bassist Artie Bernstein, and Benny Goodman on bass clarinet) and recorded “In A Mist” and the atmospheric and quirky “Dance Of The Octopus.” When he returned, Kapp hated the music so much that he tore up Norvo’s contract but those performances are considered unique recordings today.

During 1934-35 Norvo, in addition to recording two numbers with an all-star group led by Hoagy Carmichael, had better luck with Columbia, producing eight hot swing sides while utilizing such sidemen as trumpeter Bunny Berigan, trombonist Jack Jenney, clarinetists Artie Shaw and Johnny Mince, tenor-saxophonists Charlie Barnet and Chu Berry, and pianist Teddy Wilson. Among the highlights are “Old Fashioned Love,” “Honeysuckle Rose,” and “Bughouse.” He also recorded for the first time with his wife.

By then, Mildred Bailey had gone from obscurity to becoming one of the most popular singers in jazz. Her little girl’s voice (which was a contrast with her large shape) and her ability to sing anything from romantic ballads to lowdown blues had made her a major name. During 1933-35 she uplifted such numbers as “Is That Religion,” “There’s A Cabin In The Pines,” “Ol’ Pappy” (sung with a Benny Goodman group that included Coleman Hawkins), “Someday Sweetheart,” and four songs (including “Squeeze Me,” “Honeysuckle Rose,” and “Downhearted Blues”) on which she holds her own with the quartet of Bunny Berigan, altoist Johnny Hodges, Teddy Wilson, and bassist Grachan Moncur.

In late-1935, Red Norvo formed a pianoless septet that in addition to trumpet, clarinet, and tenor, had Eddie Sauter not only contributing advanced arrangements but playing mellophone. While Bailey did not record with that unique group, she sang with them on the radio. By mid-1936, Norvo had transformed the unit into a more conventional little big band, one with three trumpets (including Stew Pletcher), one trombone, three reeds, a four-piece rhythm section, the xylophonist, and Mildred Bailey. Sauter contributed the adventurous arrangements. Due to the early success of the group, Norvo and Bailey became known as “Mr. and Mrs. Swing.” Few other married couples of the 1930s had as much success in jazz, both in their collaborations and in their separate careers.

The Red Norvo Orchestra, which lasted until 1942, gradually grew in size to 16 pieces. The only swing era big band to be led by a xylophonist, the group swung lightly and had its own sound. While it did not have major hits (“Please Be Kind” and “Says My Heart,” both with Bailey, were its most popular records), the orchestra was heard regularly on the radio and worked steadily during its prime years.

Apart from the big band, Norvo recorded in small groups with Teddy Wilson (most notably “Just A Mood,” “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “Honeysuckle Rose” in a 1937 quartet with Harry James) while Bailey continued her own recording career. Among her sidemen on her sessions were trumpeters Ziggy Elman, Roy Eldridge and Buck Clayton, tenor-saxophonists Ben Webster and Herschel Evans, clarinetists Artie Shaw and Edmond Hall, the John Kirby Sextet and the full Red Norvo big band. Among her best recordings were such numbers as “For Sentimental Reasons,” “More Than You Know,” “There’s a Lull In My Life,” “It’s The Natural Thing To Do,” “Just A Stone’s Throw From Heaven” and “The Lamp Is Low.” A session in 1939 with a quartet that included pianist Mary Lou Williams featured Bailey singing stomps (“There’ll Be Some Changes Made” and “Barrelhouse Music”), the ballad “Prisoner Of Love,” and three lowdown blues associated with Bessie Smith in the 1920s. At 32, Mildred Bailey was at the height of her powers.

In 1939, the Red Norvo Orchestra broke up for a time. Bailey spent a few months as a member of the Benny Goodman Orchestra, recording eight numbers. She rejoined the new Norvo big band in 1940 but there was little interest in this unit which had only had one record date. Bailey sang on three of the four songs including “I’ll Be Around” and “Arthur Murray Taught Me Dancing In A Hurry” before it broke up in 1942. That year was also the end of the singer’s marriage to Norvo. They had grown in different directions and Bailey’s general feelings of inferiority (exasperated by her constant weight problems), low self-esteem, excessive drinking, and mood swings led to their divorce. She and Norvo would remain friends and even work together now and then in her later years.

Despite her domestic situation and increasingly erratic health, Mildred Bailey remained in her musical prime. She continued to perform on a regular basis, made some V-Discs during the war years, was part of the famed Esquire All-American jazz concert in Jan. 1944, and retained her popularity. During 1944-45 she hosted a regular radio show on CBS, Music ‘Til Midnight, for seven months. These now-legendary programs teamed her with jazz all-stars and a house band arranged by Paul Baron and often including Teddy Wilson. While some of the programs have been reissued through the years, most have not. Hopefully someday an enterprising label will make all of the shows available for this is probably the most significant jazz radio series that has not yet received the “complete” treatment.

After Music ‘Till Midnight went off the air, the remainder of Mildred Bailey’s life was anti-climactic. She continued performing as a single for a few years, recording eight songs apiece in 1945 and 1946 (including “I’ll Close My Eyes” and “Lover, Come Back To Me”), and 11 in 1947. A diabetic, she was hospitalized for a time in 1949, made a slight comeback (with a final record date in 1950), and passed away from heart failure on Dec. 12, 1951 when she was just 51.

By then, Red Norvo was a bigger name in the jazz world than he had been in the 1930s. After his big band, he changed directions and switched to playing the vibraphone. Lionel Hampton was the pacesetter on the instrument but Norvo offered a cooler tone and a more relaxed style even when he played at rapid tempos. He led an octet in 1943 that included tenor-saxophonist Flip Phillips and singer Helen Ward, was also part of the 1944 Esquire All-American jazz concert, played on some of the Mildred Bailey radio shows, and led a small group in addition to recording with the Teddy Wilson Sextet. By the end of 1944, he was working with Benny Goodman, primarily in his sextet with bassist Slam Stewart. During the same period when he had a record date for the Comet label, Norvo utilized modernists Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie in addition to Wilson and Phillips, showing that swing and bop musicians could find a great deal of common ground.

Red Norvo would keep quite busy for the next 40 years. In addition to continuing to record with Goodman, he became a member of Woody Herman’s First Herd, performing with both Herman’s big band and his Woodchoppers (a nonet taken out of the orchestra). After Herman broke up the band at the end of 1946, Norvo was back with Goodman for much of the next year while still recording regularly as a leader and with all-star combos. In 1950 he put together a popular and somewhat innovative trio with guitarist Tal Farlow and bassist Charles Mingus, showing that, even without piano, drums and horns, one could have a hard-swinging group. Norvo, who straddled the line between being modern and traditional, was always flexible in his solos and his repertoire. He kept the vibes-guitar-bass trio together through 1955, later utilizing guitarist Jimmy Raney and bassist Red Mitchell. During the second half of the 1950s, he freelanced, sometimes leading a quintet or guesting as a sideman on dates, interacting with such saxophonists as Art Pepper, Ben Webster, Buddy Collette, Jack Montrose, and Benny Carter.

Norvo’s career from that point on found him often alternating between having reunions with Benny Goodman, leading his own combos, or being a featured sideman including with Frank Sinatra during a 1959 tour of Australia and with George Wein’s Newport All-Stars in 1969. Despite having hearing problems, he stayed active throughout the 1970s, recording for Concord (including with Scott Hamilton). His last major job and final recording was performing on Benny Goodman’s PBS special in 1985 that featured the King of Swing’s last big band. Norvo was heard with one of Goodman’s small groups, sounding as enthusiastic and swinging as ever.

Norvo suffered a stroke shortly after that show and retired. He passed away on April 6, 1999, at the age of 91, more than 47 years after Mildred Bailey. By then, Red Norvo was not only noteworthy for being jazz’s greatest xylophonist but one of the big seven (along with Lionel Hampton, Terry Gibbs, Milt Jackson, Cal Tjader, Gary Burton, and Bobby Hutcherson) of jazz vibraphonists. And Mildred Bailey, whose prime recordings were issued a few years ago on a limited-edition Mosaic ten-CD set (The Complete Columbia Recordings), would have been amazed to know that she was on a postage stamp.