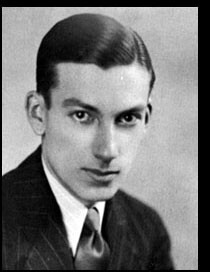

When one thinks of Hoagy Carmichael, it is often of the character that he portrayed in movies: a wisecracking pianist who offered homespun advice to his best friend (the lead actor) about romance and music. That image, which was not that different from the reality, helped mask the fact that Carmichael was a brilliant and sophisticated songwriter.

If he had only composed “Stardust,” Carmichael would have earned a spot in the history of the American popular song. However around 50 of his songs became standards, he was among the first of the piano-playing jazz-oriented singer-songwriters, and he was a major figure in the music world for over 25 years until the rise of rock pushed him into the background. While he usually did not write the lyrics to his songs, he supervised and approved the results which often expressed feelings of nostalgia for the South (although Carmichael never lived there), lost love, melancholy, and occasional outbursts of joy.

He was born as Howard Hoagland Carmichael on Nov. 22, 1899 in Bloomington, Indiana. His middle name was that of a circus troupe (the Hoaglands) that had stayed with the family when his mother was pregnant; early on Hoagy became his lifelong nickname. While his father was an electrician, his mother was a pianist who played at theaters for silent movies and at private parties. Carmichael, who grew up in Bloomington, Indianapolis, and Missoula, Montana, had piano and singing lessons from his mother as a youth. Other than some later lessons in Indianapolis, he was self-taught. He had a variety of odd jobs to help his family’s income and first played piano in public in 1918 at a fraternity dance. His parents wanted him to have a more stable career so they pushed him to work towards eventually becoming a lawyer. He attended Indiana University, graduating in 1925 and earning a law degree the following year. However by then his heart was elsewhere.

Hoagy Carmichael met cornetist Bix Beiderbecke around 1922 and they became close friends. They occasionally played music together and Bix encouraged Carmichael to also take up the cornet which he played on an irregular basis for a few years. Inspired by Beiderbecke, Carmichael began writing songs including one called “Free Wheeling.” In 1924, Beiderbecke recorded the song (which was renamed “Riverboat Shuffle”) with the Wolverines. It soon became a Dixieland standard.

Hoagy Carmichael met cornetist Bix Beiderbecke around 1922 and they became close friends. They occasionally played music together and Bix encouraged Carmichael to also take up the cornet which he played on an irregular basis for a few years. Inspired by Beiderbecke, Carmichael began writing songs including one called “Free Wheeling.” In 1924, Beiderbecke recorded the song (which was renamed “Riverboat Shuffle”) with the Wolverines. It soon became a Dixieland standard.

Carmichael made his recording debut on May 19, 1925 as a guest pianist with Hitch’s Happy Harmonists, introducing two of his other recent compositions: “Washboard Blues” and “Boneyard Shuffle.” During this era he was occasionally a bandleader, organizing Carmichael’s Collegians to play jobs. Already at this point, the 25-year old songwriter had an inventive and very personal style on the piano, and his compositions were a bit unusual, personal, and had their own logic.

Having earned his law degree, after a brief period living in Florida, Carmichael was back in Indiana, experiencing the life of a struggling jazz musician even while usually retaining a day job. 1927-31 can be considered his jazz period. In the fall of 1927 he had a bit of a breakthrough. While he recorded two numbers with “Hoagy Carmichael And His Pals” on Oct. 28 (a group that included cornetist Andy Secrest, trombonist Tommy Dorsey, and Jimmy Dorsey on clarinet on alto), more significant was the record date that he led three days later with lesser-known players. Among the three numbers (which included him being heard on cornet on “Friday Night”), Carmichael recorded the debut version of his new song “Star Dust.” It was originally devised as a medium-tempo instrumental romp as heard on this recording and it did not receive much notice at first.

Hoagy Carmichael made his first high-profile recording on Nov. 18. Paul Whiteman’s orchestra was playing in Chicago and the bandleader liked Carmichael’s “Washboard Blues” so much that he not only recorded it but featured its composer on vocal and piano in an arrangement written by Bill Challis.

Carmichael also recorded during 1927-28 with pianist Emil Seidel’s group, Jean Goldkette’s orchestra (singing “My Ohio Home” and “So Tired”), playing one number as a pianist with the Original Memphis Five and heading two sessions with Carmichael’s Collegians including two versions of the wild instrumental “March Of The Hoodlums” and one of “Rockin’ Chair.” The latter, which contained his own lyrics, originally featured Carmichael as the lone vocalist.

Knowing that the center of jazz and the music world was in New York, Hoagy Carmichael moved East in 1929, working for a brokerage house during the day while writing songs at night. He recorded frequently during 1929-30 including with the Cotton Pickers, Irving Mills (highlighted by another medium-tempo version of “Star Dust”), Eddie Lang, Frankie Trumbauer, Seger Ellis, and Louis Armstrong, sharing the vocal with Satch on “Rockin’ Chair.” From that point on, “Rockin’ Chair” would have two lives; one as a ballad vocal (after her version, Mildred Bailey became known as “The Rockin’ Chair Lady”) and as a comedy number, most notably by Armstrong 20 years later with Jack Teagarden.

Carmichael took advantage of being in New York to employ some rather major musicians on his own record dates in 1930. Bix Beiderbecke made his final recordings with Carmichael (contrasting his style and sound with trumpeter Bubber Miley on their version of “Rockin’ Chair”) and other sidemen included the cream of the white jazz scene in those segregated times: Tommy Dorsey, Jack Teagarden, Benny Goodman, Jimmy Dorsey, Pee Wee Russell, Bud Freeman, Joe Venuti, Eddie Lang, and Gene Krupa. “Georgia On My Mind” and “(Up The) Lazy River” were given classic early treatments. Clearly Hoagy Carmichael was not going to be a one-hit wonder!

And then there was “Star Dust.” It was renamed “Stardust,” given lyrics by Mitchell Parish in 1929, and the following year was slowed down in a Victor Young arrangement for the Isham Jones Orchestra, becoming a big hit. While Jones’ ballad version was an instrumental, it soon became very popular both with and without singing; Bing Crosby’s recording certainly helped. Since that period it has been recorded more than 1,500 times by virtually everyone.

By 1933, Hoagy Carmichael no longer needed a day job. Despite his prosperity, he regularly looked back with sentimental nostalgia towards his earlier days, saying that the tone and phrases of Bix Beiderbecke (who passed away in 1931) inspired some of his songs. His jazz period would always be an influence on his writing, singing, and piano playing.

After writing “Lazybones” with lyricist Johnny Mercer in 1933, Carmichael had become famous. He had a big enough name to be able to record as a leader for the Victor label, leading combos (introducing “One Morning In May” and “Moon Country”) and recording five songs as a solo pianist (highlighted by the adventurous “Cosmics”), singing on three of the latter.

In 1936, Hoagy Carmichael moved to Hollywood to work in the movie industry. While he regularly wrote music for films (starting with “Moonburn” which was sung by Bing Crosby), it was as an actor (always playing a street-wise singing pianist) that he is most remembered. He had a part in 1937’s Topper and the favorable impression that he created led to him appearing in a total of 14 films including most memorably To Have And Have Not (as Cricket singing “Hong Kong Blues” and the quirky “Baltimore Oriole” in 1942), The Best Years Of Our Lives (1946), and Young Man With A Horn (1950).

The first two decades of his Los Angeles years were busy ones for Carmichael. In addition to the film work, he wrote such songs as “Heart And Soul” (with Frank Loesser) that by the 1950s had become a very popular duet for beginning pianists, “Skylark” (with Johnny Mercer), “Two Sleepy People,” “Small Fry,” “Lyin’ To Myself,” “I Get Along Without You Very Well,” “The Nearness Of You,” “Little Old Lady,” the hot jazz of “Billy-A-Dick,” “New Orleans,” “Ole Buttermilk Sky,” “Memphis In June,” and “Doctor, Lawyer, Indian Chief.” He also composed a tune that would have been completely forgotten except that it later entered the Guinness Book Of Records as having the longest song title: “I’m a Cranky Old Yank in a Clanky Old Tank on the Streets of Yokohama with My Honolulu Mama Doin’ Those Beat-o, Beat-o Flat-On-My-Seat-o, Hirohito Blues!”

Carmichael was off records altogether during 1935-37 and only made a handful of recordings during 1938-41. But in 1942 he was very much in his element as a jazz singer-songwriter on two sessions for Decca that resulted in six titles including “The Old Music Master,” “Old Man Harlem,” “Star Dust,” and “Hong Kong Blues.” A regular on the radio (he hosted three musical variety series during 1944-48), Carmichael recorded many radio transcriptions and V-Discs, and some of his radio appearances were later released on albums. Although he compared his own singing (which was often a little flat) to how a hound dog looks, he recorded frequently for Decca during 1946-52, singing his own compositions plus a few favorite pop songs of the time.

Carmichael wrote his first autobiography The Stardust Road in 1946. He had less luck with a pair of orchestral works (1948’s Brown County In Autumn and The Johnny Appleseed Suite from a decade later) that received negative reviews. But his film career continued doing well and he received an Academy Award nominee in 1946 for “Ole Buttermilk Sky,” winning the award along with lyricist Johnny Mercer in 1951 for “In The Cool, Cool, Cool Of The Evening.”

In 1956 he recorded a superb album, Hoagy Sings Carmichael, with an 11-piece West Coast jazz group arranged by Johnny Mandel that included altoist Art Pepper and trumpeter Harry “Sweets” Edison. The 56-year old Carmichael is heard at the peak of his career singing ten of his songs.

Unfortunately from that point on, there were few remaining creative highpoints. Carmichael, who made his last significant movie in 1955 (Timberjack), had no new hits and surprisingly made no other full-length albums. He was a regular as an actor during the first TV season of the Western series Laramie in 1959, and Ray Charles’ recording of “Georgia On My Mind” in 1960 became such a sensation that many listeners thought that Charles wrote it. Carmichael frequently earned over $300,000 a year in royalties from his many songs and he kept on writing new tunes. But the rise of rock and roll and the lack of opportunities to write material for popular artists, shows, and films greatly frustrated him for the rest of his life.

Carmichael wrote a second memoir, Sometimes I Wonder: The Story of Hoagy Carmichael, which was published in 1965. But, other than infrequent appearances (he was available but few seemed interested in hiring him), he concentrated more on golf and coin collecting. Carmichael did appear as an emcee for a 70th birthday tribute concert for Louis Armstrong in Pasadena (singing “Rockin’ Chair”) and in June 1981 recorded “Rockin’ Chair” again, this time for a Georgia Fame/Annie Ross album of his songs In Hoagland, but not much else went on musically during his final 15 years.

Hoagy Carmichael passed away on Dec. 27, 1981, in Palm Springs at the age of 82. In addition to contributing so many superior songs to the Great American Songbook and bringing to the screen an original and likable character, Carmichael had paved the way for other piano-playing jazz-inspired singer/songwriters such as Dave Frishberg, Bob Dorough, Blossom Dearie, and Mose Allison. Hopefully someday, someone will explore and record some of his neglected songs from his final 30 years. One imagines that they include some unheard gems.

Fortunately most of Hoagy Carmichael’s recordings are available. The ten-CD imported set Hoagy Carmichael In Person 1925-1955 (Avid 150) has nearly everything that Carmichael recorded before his lone 1956 album, including his studio recordings (as a leader and sideman), radio broadcasts, radio transcriptions, and quite a bit of previously unissued material. The four-CD set, The First Of The Singer Songwriters (JSP 918), sticks to studio recordings (duplicating parts of the Avid box), covering the highpoints of his career during 1924-46. Mr. Music Matters (Naxos 25742) has rarities from the 1940s and Hoagy Sings Carmichael (Pacific Jazz 46862) is his classic 1956 album.

Despite his anti-climactic last act, Hoagy Carmichael left behind quite a musical legacy, filled with songs that are still being regularly recorded more than 40 years after his passing.

Since 1975 Scott Yanow has been a regular reviewer of albums in many jazz styles. He has written for many jazz and arts magazines, including JazzTimes, Jazziz, Down Beat, Cadence, CODA, and the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, and was the jazz editor for Record Review. He has written an in-depth biography on Dizzy Gillespie for AllMusic.com. He has authored 11 books on jazz, over 900 liner notes for CDs and over 20,000 reviews of jazz recordings.

Yanow was a contributor to and co-editor of the third edition of the All Music Guide to Jazz. He continues to write for Downbeat, Jazziz, the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, the Jazz Rag, the New York City Jazz Record and other publications.