When one thinks of the top alto-saxophonists of the swing era, the names of Johnny Hodges, Benny Carter and perhaps Willie Smith (from the Jimmie Lunceford band) come immediately to mind even though Jimmy Dorsey was the best known to the general public. A discussion of the great clarinetists of the 1920s always includes the names of Sidney Bechet, Johnny Dodds, Jimmie Noone and the young Benny Goodman, with Dorsey sometimes being added as an after-thought. Why is he so often overlooked?

There are two main reasons. His slightly younger brother Tommy Dorsey overshadowed Jimmy throughout much of his life, being a more successful bandleader. And Jimmy Dorsey’s many commercial recordings with his own big band have led to both him and his orchestra being underrated in the history of jazz. But a close listen to Dorsey’s best recordings show that he ranked near the top on both alto and clarinet during his lifetime. Among those who became fans of his playing were Lester Young and Charlie Parker.

Jimmy Dorsey was born Feb. 29, 1904 in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, 21 months before the arrival of brother Tommy. Their father, while he was a coal miner by day, was also a strict music teacher and a local bandleader. Both brothers were started on the slide trumpet when they were five. By the time he was seven, Jimmy Dorsey was playing cornet in his father’s band at the local Catholic Church. Two years later, he worked for two days with J. Carson McGee’s King Trumpeters and at ten when John Phillip Sousa’s band came to town, he was featured as a cornet soloist. That year, he switched his main focus to the C-melody sax and eventually alto and clarinet although he played cornet on a rare basis into the 1920s.

Dorsey’s early career often found his activities overlapping with that of his brother. They worked together and co-led Dorsey’s Novelty Six (which became Dorsey’s Wild Canaries) in 1921, broadcasting on the radio in Baltimore. From late-1921 until 1923, the Dorsey Brothers were members of the Scranton Sirens, making their debut with two obscure titles in May 1923. Jimmy Dorsey was a member of Jean Goldkette’s Orchestra during part of 1924 and that year also recorded with the Varsity Eight, the California Ramblers, and the Goofus Five. Those associations got the 20-year old’s career off and running.

While Tommy Dorsey always wanted to be a bandleader, Jimmy enjoyed being a hired gun, a studio musician who could fit into any dance or jazz band, flawlessly reading his parts and taking hot solos whenever they were called for. The first important jazz alto-saxophonist (recording several years before Benny Carter and Johnny Hodges) and equally skilled on clarinet, Dorsey could not only play jazz but was masterful at triple-tonguing on his alto like the great technician Rudy Wiedoeft.

During 1925-27, Dorsey recorded many titles with the California Ramblers, the Goofus Five, the Varsity Eight, Bailey’s Lucky Seven, Sam Lanin’s Orchestra, Fred Rich, Jean Goldkette, Red Nichols (under many different names including the Five Pennies), Cliff Edwards, the Original Memphis Five, the Charleston Chasers, the Arkansas Travelers, Frankie Trumbauer (including “Singing The Blues” with Bix Beiderbecke), Miff Mole’s Moles, the Six Hottentots, Vincent Lopez, and Carl Fenton among others.

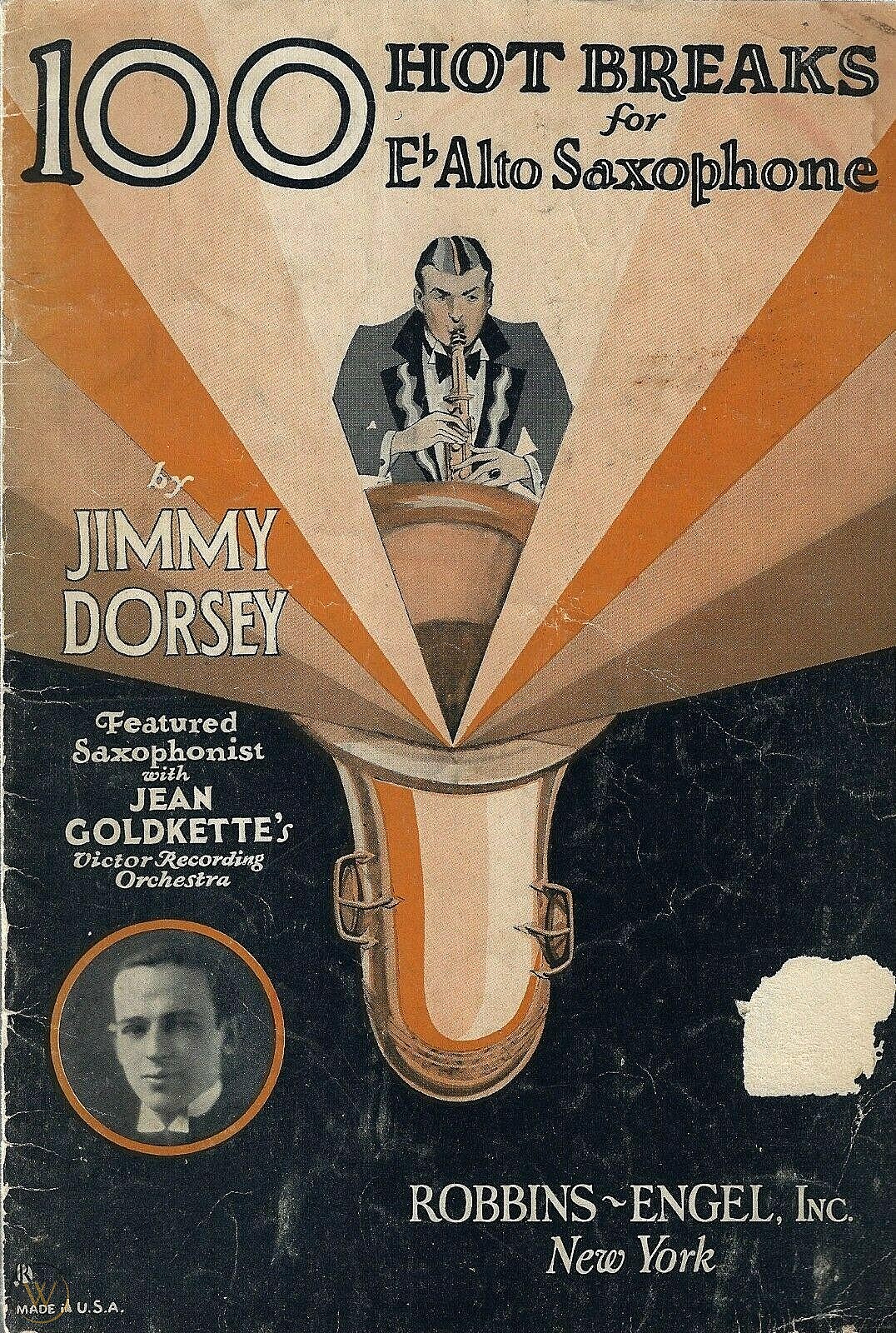

He authored the book 100 Hot Breaks for the E-Flat Alto-Sax in 1927 when he was 23 and was considered the pacesetters on alto with just a few competitors on clarinet.

Paul Whiteman was impressed by the prolific and consistently inventive reed player and he hired Dorsey for his orchestra in 1927 where he spent several months before going back to being a busy studio musician in Feb. 1928. It was during that month that for the first time recordings were made by the Dorsey Brothers Orchestra although the Dorseys did not actually have a regularly working band until 1934; before that it was strictly a studio ensemble. The early Dorsey Brothers recordings featured arrangements that were well-balanced between dance music and jazz with hot solos provided by Jimmy (and often after 1931 trumpeter Bunny Berigan) while Tommy played more melodically.

The brothers, who always loved each other, became known as “the Battling Dorseys” due to their tempers and passionate fights. While Tommy was a more extroverted and was rarely shy to say what he thought, Jimmy (who was on his way to becoming an alcoholic) was quieter and tended to bottle up his anger until he exploded. They would argue and fight about everything from music to more trivial matters, usually making up after a short period of time. Being around both of them when they were together could be a trying experience.

Jimmy Dorsey had no difficulty riding out the worst years of the Depression because he was constantly in demand for recordings and stints with radio orchestras due to his impeccable musicianship. The 1928-33 period found him recording a countless number of titles including with (among others) Sam Lanin, Ben Selvin, Boyd Senter, Seger Ellis, Red Nichols, Joe Venuti’s New Yorkers, Nat Shilkret, Annette Hanshaw, Ruth Etting, Irving Mills, Phil Napoleon, Ethel Waters, Ted Lewis, Hoagy Carmichael (including the original version of “Georgia On My Mind”), the Boswell Sisters, the Mound City Blue Blowers, and Victor Young in addition to the Dorsey Brothers Orchestra.

On May 13, 1929 he made his first recording as a leader, cutting “Beebe” (a virtuosic alto solo) and “Prayin’ The Blues.” During this era, Dorsey had a famous chorus on “Tiger Rag” that he recorded several times (sometimes on other songs that had the same chord changes) and was much admired and copied. When he toured Europe with Ted Lewis in 1930, he led a record date with a rhythm section that found him reprising that chorus on a new version of “Tiger Rag” and performing a remarkable triple-tongued solo on “I’m Just Wild About Harry.”

After being featured together on a radio show in late-1933, Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey decided to officially form the Dorsey Brothers Orchestra as a fulltime group. Glenn Miller was their chief arranger, Bob Crosby and Kay Weber were their singers, Ray McKinley was on drums, and Bunny Berigan was with the group for a few months until his drinking resulted in him being replaced.

The group mostly played dance music with occasional numbers that were hotter. Tommy Dorsey mostly functioned as the leader with Jimmy sometimes heading the band during their more jazz-oriented performances. The orchestra, which was born more than a year before Benny Goodman’s success officially launched the swing era, had potential and some success. However it came to an end on May 30, 1935 when during a performance Jimmy Dorsey questioned the tempo that Tommy had counted off on “I’ll Never Say ‘Never Again’ Again.” The trombonist stormed off and permanently left the orchestra, soon taking over the Joe Haymes Orchestra and forming his own competing big band. His older brother became the sole leader of the former Dorsey Brothers Orchestra.

Thus began the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra which lasted for 18 years. Dorsey signed with the Decca label and struggled for a long period to form an identity for the band. His orchestra had an early hit with “You Let Me Down” but commercially they were a minor league outfit. For 18 months they accompanied Bing Crosby on his Kraft Music Hall radio show and on records while also recording regularly by themselves for Decca.

Thus began the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra which lasted for 18 years. Dorsey signed with the Decca label and struggled for a long period to form an identity for the band. His orchestra had an early hit with “You Let Me Down” but commercially they were a minor league outfit. For 18 months they accompanied Bing Crosby on his Kraft Music Hall radio show and on records while also recording regularly by themselves for Decca.

Some excellent jazz musicians spent time with the band including pianist Freddie Slack, drummer Ray McKinley (the latter two had more success with Will Bradley’s orchestra which they joined in 1939), trombonist Bobby Byrne (who took Tommy Dorsey’s place), saxophonist and arranger Dave Matthews, and trumpeter Shorty Sherock.

While many of their recordings were forgettable features for singer Bob Eberly (who had a strong voice but could not uplift weak material), the band did have occasional instrumentals that were often memorable including “Dorsey Stomp,” “Parade Of The Milk Bottle Caps,” “John Silver” (which included a spirited group vocal), “Dusk In Upper Sandusky” and Dorsey’s theme song “Contrasts.” However by the end of 1940, the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra was not making much of a mark, not compared to Glenn Miller, Tommy Dorsey, Benny Goodman, Count Basie, and Duke Ellington.

That soon changed in an unexpected way. The teenaged Helen O’Connell had first joined the band in 1939 and at first she alternated solo vocals with Bob Eberly. One day, arranger Toots Camarata came up with the novel idea of having Eberly open a song with a romantic vocal chorus, Dorsey playing a brief instrumental interlude, and the always enthusiastic O’Connell swinging on the final chorus; occasionally O’Connell and Eberly would switch places. On Feb. 3, 1941, thanks to the arrangement and the two singers, Dorsey recorded what would be a giant hit with “Amapola.” Over the next year he followed it up with “Green Eyes,” “Tangerine” (introduced in the film The Fleet’s In), and “Brazil.” The 1942 film I Dood It, which starts out with the Dorsey band playing an exciting version of “One O’Clock Jump,” features the O’Connell-Eberly team introducing “Star Eyes.”

Finally the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra had made it very big. It was a bit ironic that Dorsey’s biggest sellers (which also included “Besame Mucho”) featured only brief moments from the leader’s alto and clarinet, but he was able to prosper for several years due to the vocal hits. Dorsey also had success as a songwriter with “I’m Glad There Is You” and “It’s The Dreamer In Me.” As the 1940s progressed and the big band era ended during 1945-46, Dorsey was able to keep going due to his fame although the hits stopped. The rise of bebop did not result in Dorsey altering his playing style although he did employ a few bop-oriented players in his band along the way including Red Rodney in 1944 (a period when the trumpeter actually sounded a bit like Harry James), guitarist Herb Ellis (who with Dorsey’s pianist Lou Carter and bassist Johnny Frigo eventually left to form Soft Winds), and the phenomenal high-note trumpeter Maynard Ferguson for a few months in 1949.

Dorsey actually had a stronger affection for Dixieland than he did for bebop. Unlike many of the other key swing era bandleaders, he did not form a small combo out of his big band, at least not until 1949 when he put together The Original Dorseyland Jazz Band. The octet, which included trumpeter Charlie Teagarden, trombonist Cutty Cutshall, pianist Dick Cary, and drummer Ray Bauduc with Dorsey mostly on clarinet, recorded several sessions during 1949-50 of heated Dixieland with Dorsey sounding quite credible in the exciting ensembles.

That combo was a happy distraction from grimmer realities. The big band business was in bad shape by 1950 and the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra was struggling. They made it into 1953 but by then Dorsey was bankrupt and had to reluctantly give up his big band.

While the relationship between Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey was never overly peaceful, they had collaborated on a few brief occasions in the 1940s including most notably starring in the fictional 1948 film The Fabulous Dorseys. The Hollywood movie featured them playing themselves (neither were great actors) in a very fictional screenplay and performing some of their hits although the highpoint was Art Tatum leading a jam session that include the Dorseys on an uptempo blues. In 1953 they decided to join forces again with Jimmy Dorsey joining his brother’s band which was sometimes called the Dorseys Brother Orchestra or the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra featuring Jimmy Dorsey.

While Jimmy was named co-leader, Tommy Dorsey was the real force behind the band which was essentially a nostalgia orchestra that mixed together sentimental vocals, ballads, and recent show tunes with some hot swing and solos by Jimmy, Tommy and trumpeter Charlie Shavers. The Dorseys were fortunate to appear on a Jackie Gleason television special on CBS and that success resulted in Gleason producing Stage Show, a weekly variety program that featured the Dorsey Brothers during 1954-56. While the music emphasized swing, their program was one of the first to feature a televised appearance by Elvis Presley.

Jimmy Dorsey was not overly happy during this final period (most photographs from this era do not show him smiling) but the financial security and his general lack of responsibility for the band’s survival made him content. In addition to the television show, the combination of the Dorseys was still reasonably popular and they performed regularly in clubs and occasionally on the radio.

In the early morning of Nov. 26, 1956, Tommy Dorsey died in his sleep when he was just 51. Jimmy Dorsey, who was already suffering from throat cancer, was devastated. He continued performing with the orchestra although trumpeter Lee Castle took over many of the leadership duties, Ironically as his health steadily declined, Dorsey’s recording of “So Rare” (from Nov. 11) became his first hit in a decade, reaching #2 on the charts and selling over a half million copies. It was cut at what would be his final recording session.

Jimmy Dorsey passed away on June 12, 1957 at the age of 53. While his accomplishments have often been overlooked, a fresh appraisal of his best work will result in the discovery of quite a few musical treasures.

Since 1975 Scott Yanow has been a regular reviewer of albums in many jazz styles. He has written for many jazz and arts magazines, including JazzTimes, Jazziz, Down Beat, Cadence, CODA, and the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, and was the jazz editor for Record Review. He has written an in-depth biography on Dizzy Gillespie for AllMusic.com. He has authored 11 books on jazz, over 900 liner notes for CDs and over 20,000 reviews of jazz recordings.

Yanow was a contributor to and co-editor of the third edition of the All Music Guide to Jazz. He continues to write for Downbeat, Jazziz, the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, the Jazz Rag, the New York City Jazz Record and other publications.