They were three of the greatest jazz guitarists of the 1930s although they have been overshadowed in the jazz history books by Eddie Lang, Django Reinhardt, and Charlie Christian. Carl Kress, Dick McDonough and George Barnes each spent major parts of their careers as studio guitarists, uplifting the music of others while only having occasional sessions of their own. While Lang (1902-33) set the standard for acoustic guitarists of the 1920s, by 1926 Kress and McDonough were following a similar path of balancing jazz and dance band dates. Barnes was from a later generation and mostly played electric guitar but, like McDonough, his career included important collaborations with Kress.

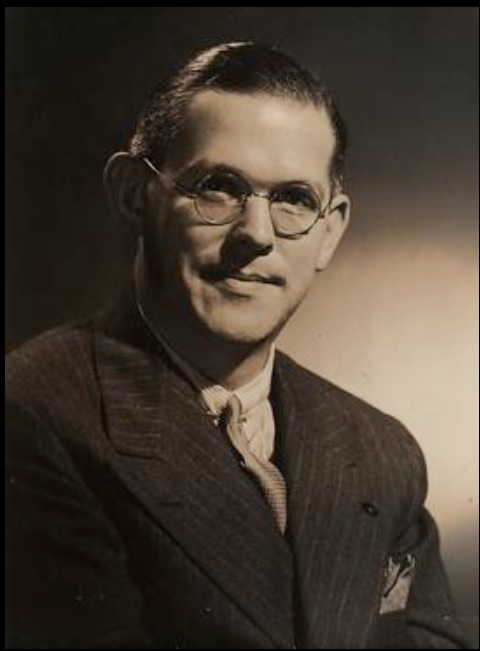

Dick McDonough was born July 30, 1904, in New York City. He began playing banjo and mandolin as a teenager in high school. His first musical jobs were when he was attending Georgetown University, playing on weekends and leading a band. During that period he developed his own style before he ever heard Eddie Lang. While attending Columbia Law School, the lure of playing with bands in New York doomed his law career.

McDonough made his recording debut in August 1925 as a banjoist with Ross Gorman’s Earl Carroll Orchestra, an organization that included cornetist Red Nichols and trombonist Miff Mole. By the following year McDonough was already an increasingly busy studio musician. Sensing the musical changes that were taking place due to the improvement in recording techniques, he began studying the guitar which he soon began using as a double and, by 1927, as his main instrument. Like Lang, McDonough was equally skilled at both creating advanced chords to accompany singers and utilizing swinging single-note lines while soloing.

During the next decade, there was an endless amount of work for the guitarist in groups ranging from hot jazz combos to anonymous studio orchestras. While Eddie Lang was better known, McDonough was just as busy. Among the groups that he recorded with during 1927-33 were many that were organized by Red Nichols (the Five Pennies, the Red Heads, and the Charleston Chasers) plus bands headed by Miff Mole, Jimmy Lytell, Don Voorhees, Ben Selvin, New Orleans Black Birds, Jack Pettis, Annette Hanshaw, Fred Rich, Jack Purvis, Benny Goodman (1930-31 and 1933), Red Norvo, Connee Boswell, the Boswell Sisters, Victor Young, Lee Wiley, the Dorsey Brothers, Adrian Rollini, Joe Venuti (including a set from Oct. 2, 1933 in an all-star sextet that included Benny Goodman, Bud Freeman and Adrian Rollini), Bing Crosby, Ethel Waters, Lee Wiley, and even Mae West.

Carl Kress was born three years after McDonough, on Oct. 20, 1907, in Newark, New Jersey. For a period, he had a career that was similar to McDonough’s despite their different styles. While his first instrument was the piano, Kress soon learned the banjo and, by the time he joined Paul Whiteman’s orchestra in 1926, he was a guitarist. Kress did not stay with Whiteman long for he found himself in great demand as a rhythm guitarist. Kress was a master at creating dense and rich chord voicings, rarely playing single-note runs in his occasional solos. He was as busy in the studios as Lang and McDonough and was on a countless number of sessions, uplifting the accompaniment given to singers, large orchestras, and occasional jazz combos. While not a major name to the general public, Kress appeared on many sessions by Red Nichols (mostly during 1927-31) along with dates by Miff Mole, the Cotton Pickers, the All Star Orchestra, the Dorsey Brothers Orchestra, Boyd Senter, Ben Selvin, Frankie Trumbauer (“There Comes A Time,” “Jubilee,” and “Mississippi Mud”), Paul Whiteman (“San”), Nat Shilkret, Fred Rich, Irving Mills, and Arthur Schutt among many others.

As with every acoustic guitarist of the era, there was always the problem of being heard but Kress found his spots and was greatly valued by his fellow musicians. He was always fond of participating in guitar duets and his most famous early session was a pair of memorable meetings (“Pickin’ My Way” and “Feeling My Way”) with Eddie Lang. While the latter was renowned for his own chordal playing, in what could be considered a tribute to Kress’ brilliance in that area, Lang confined himself during their encounters to playing single-note lines and bass lines.

Eddie Lang’s unexpected death on Mar. 26, 1933, left the field open to McDonough (who took Lang’s place on a recording by violinist Joe Venuti) and Kress although they certainly did not need the extra work. It might have been the Depression but both of the guitarists remained extremely busy.

Given Kress’ fondness for guitar duets and the fact that they were at the top of their field in the studios and employed by overlapping radio orchestras, it was inevitable that McDonough and Kress would get to play together. They had been crossing paths regularly since at least 1928 when they occasionally were both part of a Ben Selvin session. On Jan. 31, 1934, Kress and McDonough recorded as a guitar duo on “Stage Fright” and “Danzon,” a pair of tightly-arranged and stimulating performances. Two years later they performed “Heat Wave” as a duet on a radio show (Swingtime At NBC) that was released last year on a Mosaic box set. On the Saturday Night Swing Club show of June 12, 1937, they performed “Chicken A La Swing” and “I Know That You Know.” In all cases, McDonough’s single-note lead matched perfectly with Kress’ sophisticated chords.

Dick McDonough was on many other jazz sessions during 1934-37 including dates with Benny Goodman that the clarinetist made prior to forming his big band, Mildred Bailey, Adrian Rollini, Johnny Mercer, Cliff Edwards, Gene Gifford, Ramona, Jack Shilkret, Billie Holiday (including “Summertime” and “Billie’s Blues”), Red McKenzie, and Glenn Miller (a pickup group in 1937). His most notable jazz session as a sideman during this period was on two titles (“Honeysuckle Rose” and “Blues”) with an all-star quintet simply titled “Jam Session At Victor.” McDonough held his own with Bunny Berigan, Tommy Dorsey, Fats Waller, and drummer George Wettling during those joyous performances and took fine solos.

While jazz guitarists on rare occasions during the 1920s and ’30s led their own sessions, they tended to be small chamber groups. Dick McDonough, who had recorded an unaccompanied “Honeysuckle Rose” in 1934, during 1936-37 led no less than a dozen sessions (46 selections) as the head of medium-size groups with such sidemen as Bunny Berigan, Babe Russin, Jack Jenney, Claude Thornhill, and Artie Shaw occasionally in the supporting cast. Nearly all of the performances by his radio band had vocals (including by Buddy Clark and Chick Bullock), the guitarist only took a few solos, and the music straddled the boundary between dance music and jazz. However those intriguing recordings make one wonder what type of future McDonough might have had if he had lived a couple decades longer.

Dick McDonough, who was an alcoholic whose health declined during his final year, collapsed while working in the NBC studios on May 25, 1938, from pneumonia. He was just 33. If he had survived, would he have followed the path of sticking to his acoustic instrument like Carl Kress, or would he have embraced the electric guitar like George Barnes?

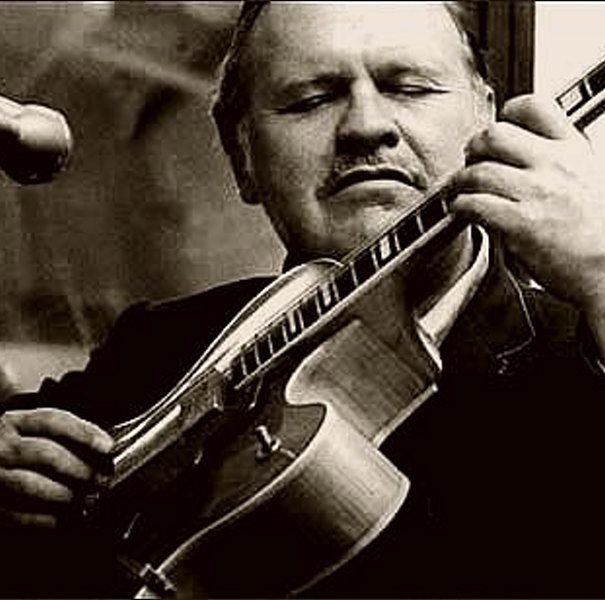

Born on July 17, 1921, in South Chicago Heights, Illinois, George Barnes began on the piano when he was five. Due to his family being tossed into poverty by the Great Depression, they were forced to sell their piano a few years later, but fortunately still owned an acoustic guitar. Barnes’ father (who was also a guitarist) gave him his first lessons when he was nine. Just a year later, his brother built him a primitive pickup and amplifier. Decades later, Barnes would say that he was the first electric guitarist although Les Paul also claimed that distinction for himself. After hearing records featuring Bix Beiderbecke and Joe Venuti, Barnes knew that he wanted to be a jazz musician. He joined the Musicians Union when he was 12, played at dances and weddings, and had some lessons from the masterful bluesman Lonnie Johnson. From the start, Barnes was much more interested in being a soloist than a rhythm guitarist, considering horn players to be his main inspirations rather than other guitarists.

As a teenager, Barnes led his own quartet in the Midwest during 1935-37 and was one of the very jazz guitarists of the era to lead his own regularly working group. In 1937 he headed an octet called the Rhythm-Aires, writing all of their arrangements. On March 1, 1938, Barnes became the first musician to record on electric guitar, debuting on “Sweetheart Land” and “It’s A Low-Down Dirty Shame” on a date led by blues guitarist Big Bill Broonzy. It took place 15 days before Eddie Durham first recorded on electric guitar with the Kansas City Five. The versatile Barnes worked in clubs with clarinetist Jimmie Noone, became a house guitarist and arranger for the Decca label, was hired as a staff member at NBC, had a regular gig at the Three Deuces in Chicago, and recorded with such blues artists as Curtis Jones, Washboard Sam, Jazz Gillum, Louis Powell, Blind John Davis, Merline Johnson, and Hattie Bolton. He was still just 17.

In 1939 Charlie Christian became the first famous electric guitarist. While Christian and many of those who followed him (including Tiny Grimes, Barney Kessel, Tal Farlow, and Herb Ellis) became well-known, Barnes never gained much fame. Instead of becoming part of a swing band or heading his own jazz sessions, he pursued the life of a studio musician during the next 20 years. He was always a swing-based guitarist and played jazz when called upon but was also employed, mostly in an anonymous role, to play pop, country (including with Patsy Cline), novelties, and eventually rock and roll behind other artists.

In 1940, Barnes had his first record date as a leader, playing in a quartet and sounding impressive on “I Can’t Believe That You’re In Love With Me,” “Little Rock Getaway” (which was not released for over a half-century), and “I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles.” He was drafted and was in the Army from 1942 into early 1946. After his discharge, Barnes went back to being a studio musician. For the fun of it, he formed the George Barnes Octet, an unusual group that also included four woodwinds (with a combination of clarinet, bass clarinet, English horn, oboe, flute, and piccolo) plus rhythm guitar, bass, and drums-vibes. The Octet had a 15-minute radio show on ABC and made some radio transcriptions that were released many years later. Barnes, who wrote the arrangements and a few originals, was the group’s only improviser and soloist. That venture (heard on the Hindsight release The Uncollected: George Barnes And His Octet 1946) was just a temporary departure although there was a much later LP (Guitar In Velvet) by a similar octet.

Barnes, who led eight titles for the Keynote label in 1946 with a more conventional sextet, was heard in jazz settings now and then during the 1946-61 period including sessions led by Bill Harris, Anita O’Day, Artie Shaw, Coleman Hawkins, the Lawson/Haggart Band, Jimmy McPartland, Bud Freeman, Ray Anthony, George Wettling, Steve Allen, Big Joe Turner, Johnny Guarnieri, Joe Venuti, Wingy Manone, and Lou Stein, but that was only a small fraction of his daily output. He was on Louis Armstrong’s Musical Autobiography but was miscast; his electric guitar was a poor substitute for Johnny St. Cyr’s banjo on remakes of the Hot Five and Seven recordings. Barnes, who moved to New York in 1951, also led some albums of his own in the 1950s although most are somewhat commercial or a bit gimmicky. Guitars – By George is an LP on Decca from 1951-53 that has Barnes using multi-tracking to create a one-man band a la Les Paul while his 1961 album Guitar Galaxies had him joined by no less than ten other guitarists, one of them being Carl Kress.

While largely unknown to everyone other than his fellow musicians, Carl Kress continued working steadily during 1936-61, usually well buried in large ensembles. There were rare exceptions including his five unaccompanied guitar solos from 1938-39 (“Peg Leg Shuffle, “Helena,” “Love Song,” “Sutton Mutton,” and the three movements of “Afterthoughts”), ten guitar duets with Tony Mottola in 1941 that were released as radio transcriptions, and an obscure four-song session that he led in 1946. Kress also recorded with Frankie Trumbauer (1936 and 1946), Three’s A Crowd (a trio with clarinetist Paul Ricci and pianist Jerry Sears) in 1938, Toots Mondello (1939), Edmond Hall (1942), a Dixieland group co-led by Will Bradley and Yank Lawson (1944), Billie Holiday (the original version of “Lover Man”), Red McKenzie (1944), Yank Lawson, Muggsy Spanier, Bobby Hackett, Bud Freeman, Jimmy Dorsey’s Original Dorseyland Jazz Band (1949), Bob Crosby, and Jack Teagarden, fulfilling a similar role as George Van Eps in Dixieland settings.

In 1958 Carl Kress and George Barnes first recorded together, making a duet album for the Music Minus One label. In late-1961 they formed a duo that, while not being inevitable, was certainly logical. Barnes’ single-note lead was a perfect match for Kress’ sophisticated chords. Working together, they were able to escape from the studios with both of the masterful guitarists finally gaining some long overdue recognition from the jazz world. Six albums resulted from their collaboration: Two Guitars, Two Guitars and a Horn, Something Tender (tenor-saxophonist Bud Freeman is on half of the former and all of the latter), Town Hall Concert, Guitars Anyone, and the little-known Smoky And Intimate which has the guitarists accompanying singer Flo Handy. Kress and Barnes also performed at the Lyndon Johnson White House on Dec. 17, 1964, for a Christmas party. Taken as a whole, the music by the two swing guitarists was happily out of place in the jazz world of 1962-65.

It all ended on June 10, 1965 when the 57-year old Carl Kress died from a heart attack while the duo was on tour. George Barnes, who was still not quite 44, continued on in the jazz world, taking many less studio assignments to devote himself to more creative music. He had a guitar duo with Bucky Pizzarelli during 1969-72 that recorded one album (Guitars Pure & Honest) and a few songs for the multi-artist Guitar Album, and led his own quartet record for the Famous Door label (Swing Guitar).

Barnes also found a new musical partner in cornetist Ruby Braff. During 1973-75, the Ruby Braff-George Barnes Quartet, which also included rhythm guitarist Wayne Wright and John Giuffrida or Michael Moore on bass, worked steadily, recorded seven albums (The Ruby Braff-George Barnes Quartet, Live At The New School, Plays Gershwin, Salutes Rodgers and Hart, and To Fred Astaire With Love plus two other Rodgers & Hart collections with Tony Bennett), was a regular at jazz festivals, and helped jumpstart the comeback of small-group swing. Barnes was very much an equal partner with Braff and, to a large extent, he is chiefly remembered today for this group.

George Barnes also had a shorter collaboration with another jazz great. He and violinist Joe Venuti recorded two albums during 1975-76. While it would be tempting to compare Barnes’ role in those combos with that of Eddie Lang with Venuti more than 45 years later, in reality the guitarist’s role was as another horn soloist rather than as an accompanist to the violinist. The combination worked quite well as they challenged each other on their two Concord releases Gems and Live At The Concord Summer Festival.

As was true with Dick McDonough and Carl Kress, George Barnes remained active up until the end of his life. He recorded three very good albums in 1977 (Blues Going Up, Plays So Good, and Don’t Get Around Much Anymore) with his quartet which also included rhythm guitar, bass, and drums, mostly playing the swing standards that he loved. Don’t Get Around Much Anymore is a live session from July 27, 1977. 40 days later, George Barnes, who was one year younger than Kress had been at the end of his life, died from a heart attack at the age of 56.

Fortunately Carl Kress, Dick McDonough and George Barnes are well represented on records. In addition to the ones already mentioned, there are two other albums that are highly recommended. Pioneers Of Jazz Guitar (Challenge), along with a dozen small-group features for Eddie Lang from 1927-28, has the two remarkable Kress-Lang duets, four of the Kress-McDonough encounters, and all of Carl Kress’ solos of 1938-39. The Yazoo LP Fun On The Frets includes the ten Kress-Mottola duets of 1941, the 1936 radio duet of Kress and McDonough on “I’ve Got A Feeling You’re Fooling,” and a George Van Eps studio session from 1949. Those two albums serve as obvious evidence that there were more contributors to the development of early jazz guitar than Eddie Lang, Django Reinhardt, and Charlie Christian.

Since 1975 Scott Yanow has been a regular reviewer of albums in many jazz styles. He has written for many jazz and arts magazines, including JazzTimes, Jazziz, Down Beat, Cadence, CODA, and the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, and was the jazz editor for Record Review. He has written an in-depth biography on Dizzy Gillespie for AllMusic.com. He has authored 11 books on jazz, over 900 liner notes for CDs and over 20,000 reviews of jazz recordings.

Yanow was a contributor to and co-editor of the third edition of the All Music Guide to Jazz. He continues to write for Downbeat, Jazziz, the Los Angeles Jazz Scene, the Jazz Rag, the New York City Jazz Record and other publications.